If Godzilla did not exist, it would be necessary to invent him

But let's not sell it short: the human material is still pretty strong on its own right, strong enough that I would have been perfectly happy to watch Godzilla Minus One even if it was totally free of Godzilla altogether, though I say that in the full knowledge that I have a lot more affection for Japanese melodramas from the decade following the Second World War than an American living in the 2020s is likely to have, so what makes me perfectly happy would not necessarily make you perfectly happy. Either way, it is, in fact, a post-war melodrama we have here, and a solid one, if that's your bag: once upon a time there was a kamikaze pilot named Shikishima Koichi (Kamiki Ryunosuke), who was assigned to a suicide run late enough in 1945 that it was very clear that Japan wasn't going to win, and between that knowledge and his desire not to die, Koichi has decided to pretend that his plane doesn't work. So he lands on an island in the southern part of the Japanese archipelago for "repairs", which chief mechanic Tachibana Sosaku (Aoki Munetaka) immediately recognises don't need to be made. But anyway, it's too late for Koichi to take back off, and Tachibana recognises that this is all futile as much as anybody, so this all seems likely to disappear into the fog of war as the men on the island bed down for the night. In the darkness, the island is visited by a creature like an enormous Tyrannosaurus Rex, a good 25 or 30 feet tall or more, known by the native islanders and called by them "Godzilla". It devours its way through the soldiers, with Tachibana imploring Koichi to use his plane's guns to take the animal down; Koichi freezes in terror, and witnesses every other human than Tachibana die.

A few months later, Japan is a bedraggled disaster, so torn apart that it's not even clear where the rebuilding needs to start, and this is where we get our actual story. Koichi is consumed by guilt and aware that the rigid honor codes governing his society even in its ruinous state means that anyone who learns about his dereliction of duty will view him as the worst kind of coward, so he throws himself into a dangerous job as a way of atoning: acting as the gunner on a minesweeper vessel, working to clear the waters around Tokyo from the explosives planted there by both the Japanese and the Americans. He also begins to pick up a little found family of lost souls: Oishi Noriko (Hamabe Minami), who lost her family during the war just as Koichi did, and little baby Akiko, who was pressed into Noriko's arms by a dying mother whose last thought was for the safety of her child, and a kind of judgmental mother-in-law figure in Ota Sumiko (Ando Sakura), an older woman who lost her children in the war and clearly views Koichi with contempt for his wartime actions, but isn't about to let a small child suffer just because she disapproves of the people who've taken her in. That gets us a nice chunk of the way through the well-paced 124 minutes, just watching as Japan tries to find a way to crawl out of its own wrack and ruin, while our two young adults take stock of how wounded they and dance around the possibility of forming an actual family with each other, and not just a simulacrum of one. And I, for one, thoroughly enjoyed it all. Kamiki is quite a veteran for a young actor, having worked since childhood in both live-action and animation (he's done voice work for both Studio Ghibli and blockbuster director Shinkai Makoto, including voicing the male lead in the enormously successful Your Name.), and he brings a lot of fine shading to his melodramatic lead role; I think Godzilla Minus One would still be perfectly fine without him, but it's an enormous benefit to the film that the lead performance is so delicately balanced between mortified guilt at being a coward, and a small kernel of stubbornness at the knowledge that his death would have done absolutely nothing whatsoever to turn the tide of war in Japan's favor. "What facet of Japan's role in global geopolitics does this film address?" is a question that you can ask of virtually every single Japanese-made Godzilla film, even some of the very junkiest kids' movie ones, and in the case of Godzilla Minus One, it's about pondering the low value placed upon human life by Imperial Japan, and how everybody who lived in that world prior to 1946 just kind of went with it, and how that is very weird and fucked. The arc of the story, expressed in very unsubtle and blunt terms (this is, after all, a post-war romantic melodrama that transforms partway through into an action-horror movie about a skyscraper-sized dinosaur who eats ships and shoots nuclear beams out of its mouth; it has very little reason to aspire to subtlety), is that if Japan is going to get back on its feet and join the international community that emerged from WWII, it would need to leave behind the death-cult aspects of its former identity. No more kamikaze, no more treating the individual human life as something to be disposed of without compunction.

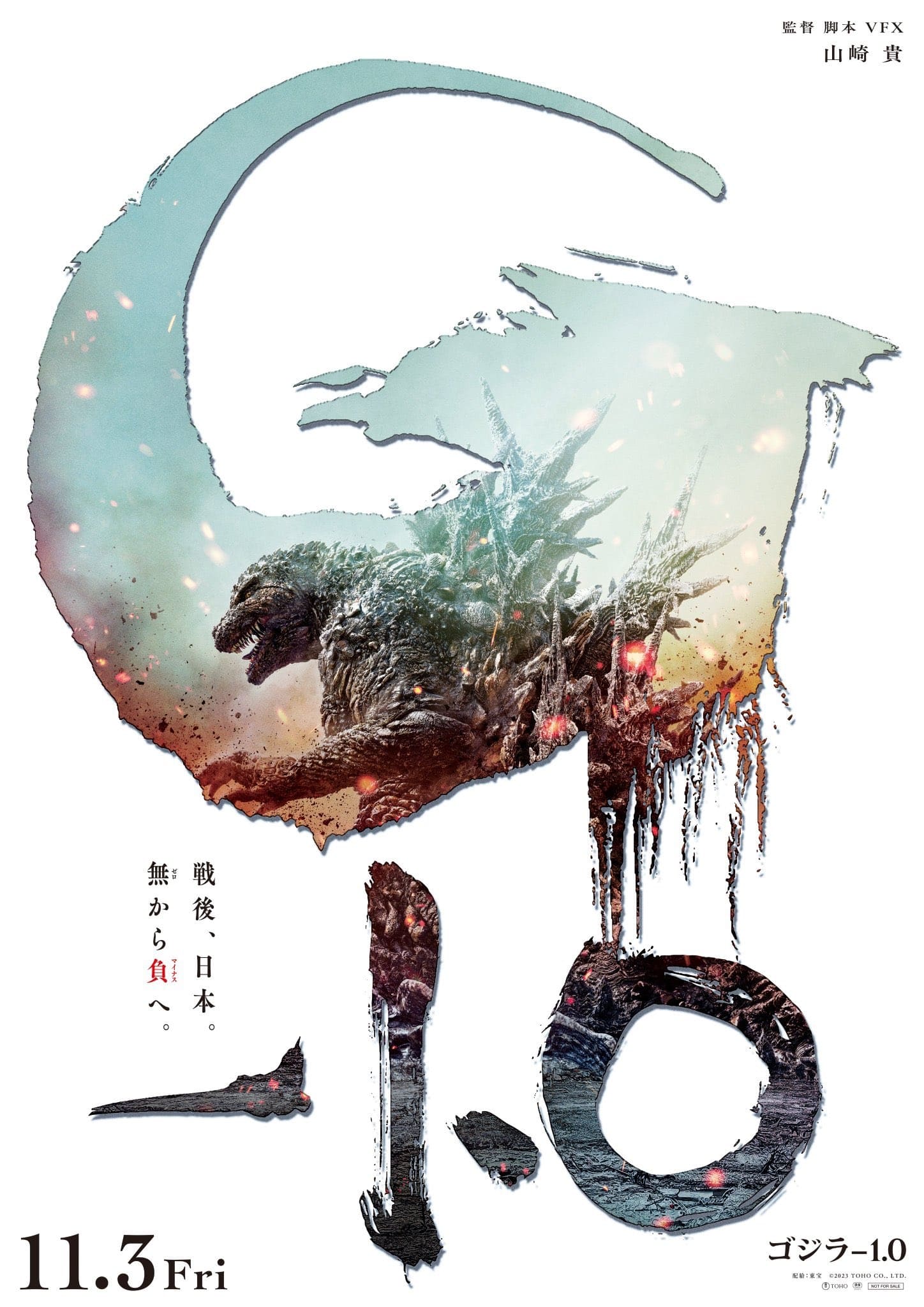

All of which is well and good, acted gracefully, and directed by Yamazaki Takashi (who also wrote the script, and served as visual effects supervisor, which is the kind of three-part hyphenate you don't see much of in Hollywood) with the correct amount of mawkishness for it all to seem emotionally earnest without being tacky or breast-beating or any such thing, except in carefully controlled doses. It's also, admittedly, a bit narrow in its appeal, which is where the aforementioned skyscraper-sized dinosaur comes in: nuclear testing in the Pacific has had quite a beneficial impact on Godzilla, who is now big enough to be able to fit its entire mouth around a battleship. And this is the point where Godzilla Minus One gently sets aside its story of post-war national identity - gently, mind you, Godzilla is still as much a metaphor for Japan's violent past as it is big-ass firebreathing creature, just like in every movie - and becomes, a bit surprisingly and very delightfully, 2023's best action-adventure popcorn movie. I'm not the first and I won't be the last to note that the film cost a whopping $15 million or so to make, and while it's not exactly fair to compare different industrial contexts, it's pretty fucking astonishing - not to mention irritating, really - that Godzilla Minus One genuinely looks better than American movies costing more than ten times as much. Setting aside absolutely everything it does with its visual effects, either at the level of story or simply in terms of spectacular image-making: the effects here look so great. Like Shin Godzilla before it, Godzilla Minus One replaces the beloved man-in-a-rubber-suit of the series' history with an all-CGI Godzilla, with great care having gone into making the CGI model look like a rubber suit, and to a certain extent making the CGI Tokyo that it rampages into look like it is made out of 4-foot tall model buildings. Which, to my mind, increases the bar for success: weightless animated monsters are one thing, but the great appeal of the Godzilla suits is their touchable physicality, the way you can sense the models and the latex and the studio walls. Godzilla in this movie feels physical: the texturing has actual texture to it and everything. It's the sort of thing that one "knows" has been missing from big-budget American popcorn movies of late, but you don't realise how precious that kind of thing is until it's suddenly right there in front of you, proudly showing off its illusory tangibility.

So the technical quality of the effects is great. So, happily, is the artistic quality. This Godzilla immediately leaps onto my top tier of Godzilla designs of all time: besides having some of the best body proportions in the monster's history, it also has a fantastically expressive face, one that has a certain cartoony exaggeration, particularly around the deeply menacing, pissed-off eyes, but never violates the reality of the setting. It also has some wonderfully goofy grace notes, such as the way its dorsal spines pop out and glow when it's time for the monster to breath its nuclear breath. So it looks pretty neat, a terrifically distinctive character like no other CGI Godzilla has been (in a great many ways, this feels like the movie to "fix" the 2014 American Godzilla: they have some very similar ideas, both in narrative situation and the way they try to make Godzilla seem massive, and I would without hesitation say that the shared ideas are all much better here, and also this film has nowhere near the same flaws as that one, even as I continue to think that it's the only one of the American Godzillas of the last decade that's worth a damn). But it's still necessarily CGI, which is what's great about this film's effects: Yamazaki and his team are using the latitude of computer animation to push their Godzilla to do things that no stuntman in a rubber suit could have possibly down, constrained as they all were by physics, but they also very carefully make sure that it always looks like a stuntman in a suit. As Godzilla thrashes its way through the Ginza district, in the film's big landbound setpiece (this Godzilla is primarily an aquatic animal), the flexibility and full-body vitality of its movements are like nothing else in this franchise, but it's never weightless. It's the very best kind of popcorn movie magic.

That extends to basically all of the film's Godzilla material, which is reasonably generously doled out in the back half (it's by no means the most Godzilla-heavy film on the books, but it has more screenitme for the monster than I recall in Shin Godzilla). Yamazaki has demonstrated the very best skill for any artist to possess: he knows who to steal from, and he knows how to do it well. There are lengthy passages of the film, when the minesweeper on which Koichi serves is locked in a terrifying battle with Godzilla's massive head, plowing through the water, where Godzilla Minus One just outright blatantly steals from Jaws, having already stolen (not so blatantly) from Jurassic Park in the opening sequence, so there's just whole lot of Steven Spielberg getting smeared across this film, and it's fantastic. The film's three main Godzilla setpieces in the middle and end of the film aren't just fun giant monster spectacle: they're terrific at the mechanics of thriller filmmaking, doing some of the best work in this series' history of making the monster's body seem huge and implacable and deadly and really make the humans feel like miserable little ants in the face of such godlike destructive power. Any one of them would be a pretty strong candidate for the best giant monster action setpiece ever put into a movie, and they're all in the same movie. That's a pretty remarkable achievement, all the more so since Yamazaki is able to bring in all this eye-popping spectacular nonsense into a movie that is fundamentally very serious and moody and grave - his main avowed influence was Kaneko Shusuke's 2001 Godzilla, Mothra, King Ghidora: Giant Monsters All-Out Attack, which remains the heaviest and bleakest of all Godzilla movies, and it's very easy to tell where he was trying to mimic the way that film used its goofy material to deadly serious ends (I also think Godzila Minus One is by far the better of the two movies, but my aversion to GMK is one of my biggest breaks with the majority of Godilla fandom - I frankly think it got too dark, whereas the new film, by virtue of hooking itself into melodrama for its "serious" moments, can pivot back into "rousing adventure movie" mode with relatively smooth ease). So it's basically got a little bit of anything I could want to ask for from a Godzilla movie, and if I was being as sober-minded and critical as I felt it possible to be while remaining at all honest, "one of the all-time top 5 Godzilla movies and the best thing in the series since 1995's Godzilla vs. Destoroyah" would be the absolute harshest I could bring myself to go.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

Categories: action, daikaiju eiga, horror, japanese cinema, movies about wwii, war pictures, worthy prequels