The head, the tail, the whole damn thing

For some time now, I've had people raising the question, "When are you going to review Jaws?" because as we are all aware, there are not nearly enough reviews of Jaws in this world. That said, I am not immune to begging, and when the slowest week for new releases in several months stumbled into my lap, it seemed to be as good a time as any to finally pull the trigger on writing up the film so good it invented an entirely new paradigm for how moviegoing happens. Also its sequels, which did not do that thing.

This still leaves us at the insurmountable question: what the hell am I supposed to say about Jaws, one of the most thoroughly-analysed films in history? Short of flat-out making things up (e.g. "the narrative hinges on the homosexual love affair between Richard Dreyfuss and Robert Shaw's characters") there really isn't anything left to say about the movie, only things to be reconsidered and, if I am lucky, shared with people new enough to the movie that they've managed to avoid decades of top-shelf criticism.

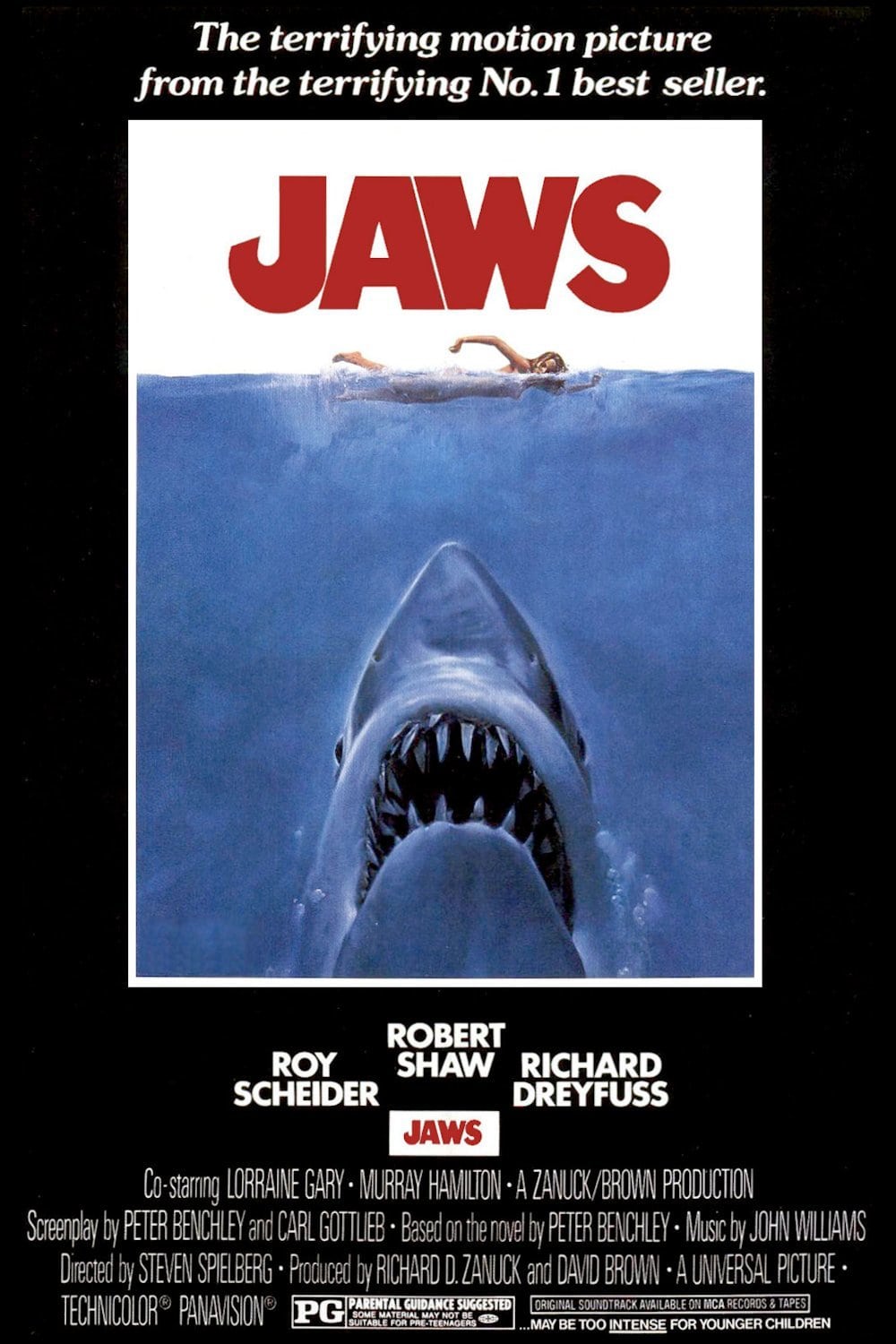

I will begin, therefore, with a bit of praise for the person who is perhaps most responsible for the film's success, and who is perhaps not often given her full due. I refer to the film's editor, Verna Fields, who has not been quite as well-remembered in latter times as the more obvious figures like Steven Spielberg and John Williams, though without her, it's doubtful that Jaws would exist in a watchable form, let alone be one of the leanest and most perfect thrillers in cinema history. It's well-known that, following an inconceivably difficult shoot, Fields was essentially given a pile of incoherent footage and told, "make it into a movie". That she did just that is already worthy of admiration; but the excellence of the editing in Jaws goes far beyond that. There's only a single one of the film's many famous and beloved and iconic-because-they-are-perfect scenes that doesn't primarily work because of the brilliant cutting, so it's at once too easy and extremely hard to come up with a single example, but let us take the opening scene: in which a young woman, Chrissie (Susan Backlinie), and a young man, Cassidy (Jonathan Filley) are going skinny dipping. Anyway, Chrissie is, while a very drunk Cassidy can't even pull his shirt off. As this happens, of course, Chrissie is attacked by something in the water - we don't know it's a shark yet, but if it is 1975 then we've seen the poster, and if it's any period between 1976 and the present day, then we simply have to not be complete idiots.

A simple, nasty, and unfathomably influential opening - Jaws didn't pioneer this sort of thing, but it made it almost impossible to stumble across a creature movie or really even a horror film generally that opens in any other way - and deceptively sophisticated. First, and obviously, there is the way Fields cuts between Chrissie and Cassidy, initially just silently demonstrating how far apart they are from each other. Then there is the matter of the attack itself, and of course it is wonderfully tense and horrifying, much of which has to do with Fields's choppy, arrhythmic cutting, and much to do with Spielberg's cunning (and, if the stories are true, semi-abusive) directing. But what I want to call your attention to, is that in all of this crazy, hectic flurry of motion, there is one and only one jump-cut; that is, only one moment at which the editing breaks with strict continuity; it is when the shark first bites Chrissie, a startling and horrifying moment, one that is made all the more jarring for us because of that violence against continuity. It's a simple thing, maybe even an obvious one - but how many movies don't do it? Anyway, it's the very definition of a filmmaking gambit that works even if (especially if) you don't notice it, and this is true of Jaws as a whole; it is the key to Spielberg's entire filmography, really, with its characteristic blend of precise filmmaking mechanics and a showman's desire to appeal to the broadest audience.

But we are not done with that scene yet: there is the occasional punctuation of Chrissie's violent death (it has been compared, several times, to a rape) with Cassidy's increasingly slow and sleepy attempts to get into the water, with the attendant shift in sound from loud to silent (this is a change from the start of the scene, where the land was full of noise and the water mostly silent) and the visual palette changing from greyish-blue and black to brownish-black. Then the last two shots (Cassidy asleep on the beach, the empty ocean with a buoy where Chrissie died) sum up the scene, before an absolutely beautiful dissolve matching the horizon line to the view from our protagonist's house.

Nothing exists in a vacuum, of course, and there are at least five distinct disciplines that all have to work together to make this scene work: the editing, the sound design, the cinematography, the musical score, and the directing and acting. But I have claimed and will stand by that claim, that the editing is something particularly special.

From here, the plot properly begins, and the next 15 minutes demonstrate one of the film's other great triumphs that tends to get ignored in favor of the more obvious (and, to be fair, more important) contributions of Spielberg's direction: Jaws has a really fucking great screenplay. This is a little bit surprising, given that it is adapted from a resolutely adequate potboiler by Peter Benchley, and a whole lot more surprising given that the adaptation was executed by Benchley himself, with assistance from TV comedy writer Carl Gottlieb. Not a prepossessing start, yet what came out of it is one of the most mechanically flawless American screenplays this side of Casablanca: assuredly, it is not idiot-proof in the way that Casablanca is, and without seeing the actual shooting script it's hard to say what Spielberg and even Fields might have done to improve any lapses. But based on the evidence we can see, the writing is pretty damn tremendous. It's one of those films where not a single line of dialogue nor a story beat is wasted; everything serves to either establish character or a situation, frequently both. The first scene with our protagonist, Martin Brody (Roy Scheider) is a perfect example: the information we need to know (he is the chief of police, he is new to Amity Island, he is something of a well-liked alien among the native islanders, he is afraid of water) is dribbled out piecemeal, explained to us with brutal efficiency and sweetened enough that it doesn't feel at all like exposition. Brody's first line is to complain about the sun in his eyes; his wife, Ellen (Lorraine Gary) points out that they bought the house in the fall. Boom, right there we know that they've moved in the last nine months, that Brody is a grumbler, two things that will matter for the whole rest of the movie, and it's established in his very first interaction with another character. That's how everything is explained: his profession and his relationship to the town, the town's reliance on tourism, the effect a killer shark would have on that tourism, and so on and so forth. It's a miracle of concision, and I will not bore you all by going through it piece by piece, but it's an incredible amount of information in very little time.

This makes a lot of sense when one steps back and considers the whole structure of Jaws: in effect, it needs to fit an entire movie in half the running time, for the entire thing is really a two-part narrative consisting of two three-act structures. The first half (actually, slightly more: 65 minutes of a 124-minute film) is the messy character-driven thriller of one man's attempt to save his town from its own stupidity, and in order to present this story in slightly more than an hour, it has to move quickly. I had never, in all the many times I've watched this film, actually paid attention to the timing of events throughout, but it is a far swifter narrative than I'd have guessed; the death of the Kintner boy, the big woomph! moment of the first third, comes all of 16 minutes into the movie, by which point virtually all of the conflicts that will define the first 65 minutes have been established.

At the same time, the first half has to not only function on its own terms of establishing a threat and building up a community that is reasonable and believable enough that we will feel anguished when it is threatened, but also to establish a foundation for the second half. It's no secret that the second part of Jaws is, on the whole, better than the first, which says more about the second part; it is tremendous filmaking in every regard, essentially a three-man play taking place entirely in one location, simultaneously a man vs. nature adventure as well as being a character drama about three incompatible people being thrust into a situation where they must work together in despite of their considerable differences of temperament and tone (it is one of the great glories of the film that at some point in the last 50 minutes, there is every possible iteration of two-against-one amongst the three used to propel some moment of conflict or another).

Incidentally, it is this point that has always made me regret when people label Jaws as the big honkin' blockbuster that ruined the New Hollywood Cinema and began the beginning of the long slow death of American filmmaking. For all it's B-movie trappings, I have, for one, always regarded Jaws as being a natural part of the New Hollywood movement in a way that e.g. Star Wars is not, for it is at heart a character study with class warfare overtones, nestled inside a shark-hunting adventure. No, it is not the most sophisticated character study of the 1970s. But I defy anyone to name a single big effects-driven blockbuster made anytime after 1975 that has even one character as sharply-drawn and richly played as the three heroes of Jaws; or to name another huge summer movie where the consensus pick for its best scene is a lengthy monologue captured in great long takes.

Nor should we begrudge the film its financial success: truth be told, it basically needed to be the first $100 million film of all time in order for Spielberg to have any career at all following. Not literally, but after going to massively far over-budget and over-schedule, a little hit wouldn't have done it; it had to be a great huge hit or the relatively green filmmaker would be persona non grata, and the future evidence of his career leads me to regard that as a bad thing, although I do happen to regard Jaws as his directorial peak, even if that is partially the result of happy accident (shark that didn't work, invisible menace, etc. - you surely don't need to hear that story again from me).

I was, however, talking about how wonderfully the film sets up its second half: the initial appearance of grizzled fisherman Quint (Robert Shaw), in what is effectively a first-act appearance of a human Chekhov's gun; the scene with the idiot shark hunters in which the floating pier stands in for the shark, foreshadowing the use of the yellow barrels later on; marine biologist Matt Hooper (Richard Dreyfuss) telling a story of how a shark destroyed his boat. And of course, the film establishes the characters in vivid detail, all the way up to the final conflict with the big 25-foot rubber doll that we thankfully only see in bits and pieces, the evident fakeness of which isn't enough to derail a film that has completely won us over by that point - I think it is sometimes overlooked that not only does the absence of the shark in the first hour work because the unseen is scarier than the seen, but because the seen in this case looks really dumb, and the film needed us on its side before it asked us to suspend our disbelief on that grey thing being a shark.

Anyway, as I was saying, the vivid character details: the reason Jaws is still better than any other monster movie or summer blockbuster ever made. Amity is a real place, with real people who even in one little moment seem to have a whole life somewhere offscreen; meanwhile, our main characters all have real honest-to-God presence and depth, some of which comes in very unexpected ways - for example, the godawful powder blue jacket with little white anchors worn by the mayor (Murray Hamilton), a marvelous touch of characterisation through costuming; or the incredible dinner table scene between Brody and his youngest son. It helps that they're impressively played, with some really nice touches. Even as broad a character as Quint has subtle moments (thank God for Shaw's performance, without which the character might have slid into cartoon excess): his little glances and facial twitches when nobody but the camera is looking - at one point, he frowns a little when Brody reluctantly sips at Quint's homemade alcohol, and it's as great a character moment as film can possess.

Anyhow: Jaws. It's a good 'un. And I have barely touched upon John William's incredible score, horns and bass strings creating a throbbing sense of menace: the main theme is clearly a response to Bernard Herrmann's famous stabbing strings in Psycho, and it is beyond question the single finest piece of horror movie music in between that film and Halloween. Any composer would be proud to call it his best work - there is one cue, during the final day's chase, where it gets a bit too sprightly for to mood of the moment, but that is the single misstep - given the incredible run of scores he wrote between 1977 and 1983, it's not much more than a warm-up, though it's still one of the chief reasons the film builds tension as well as it does.

Nor did I so much as mention Bill Butler, a cinematographer whose career is otherwise of little note - he'd eventually shoot Anaconda, so that's something - though he and Spielberg were responsible here for the very best ship-bound camerawork in film history, turning a chaotic shoot on the water into some of the smoothest, most rhythmic shots of the ocean that you will ever see no matter how many boat movies you watch and no matter who tries to make them in the future.

But that's the hell of Jaws: it is a perfect movie. Some may complain about its relative lack of thematic depth; to hell with them. It's deep enough to have a real sense of personality, and not so deep that it ceases to be an amazingly tight monster thriller, a genre film of the absolute highest order with intelligence and pretty much the best craftsmanship that ever went into the making of a film that could honestly be tagged with the label of "horror". It is, simply put, one of the absolute masterpieces of populist cinema, and worthy of more respect and love than I or any one writer could ever send its way.

Reviews in this series

Jaws (Spielberg, 1975)

Jaws 2 (Szwarc, 1978)

Jaws 3-D (Alves, 1983)

Jaws: The Revenge (Sargent, 1987)

This still leaves us at the insurmountable question: what the hell am I supposed to say about Jaws, one of the most thoroughly-analysed films in history? Short of flat-out making things up (e.g. "the narrative hinges on the homosexual love affair between Richard Dreyfuss and Robert Shaw's characters") there really isn't anything left to say about the movie, only things to be reconsidered and, if I am lucky, shared with people new enough to the movie that they've managed to avoid decades of top-shelf criticism.

I will begin, therefore, with a bit of praise for the person who is perhaps most responsible for the film's success, and who is perhaps not often given her full due. I refer to the film's editor, Verna Fields, who has not been quite as well-remembered in latter times as the more obvious figures like Steven Spielberg and John Williams, though without her, it's doubtful that Jaws would exist in a watchable form, let alone be one of the leanest and most perfect thrillers in cinema history. It's well-known that, following an inconceivably difficult shoot, Fields was essentially given a pile of incoherent footage and told, "make it into a movie". That she did just that is already worthy of admiration; but the excellence of the editing in Jaws goes far beyond that. There's only a single one of the film's many famous and beloved and iconic-because-they-are-perfect scenes that doesn't primarily work because of the brilliant cutting, so it's at once too easy and extremely hard to come up with a single example, but let us take the opening scene: in which a young woman, Chrissie (Susan Backlinie), and a young man, Cassidy (Jonathan Filley) are going skinny dipping. Anyway, Chrissie is, while a very drunk Cassidy can't even pull his shirt off. As this happens, of course, Chrissie is attacked by something in the water - we don't know it's a shark yet, but if it is 1975 then we've seen the poster, and if it's any period between 1976 and the present day, then we simply have to not be complete idiots.

A simple, nasty, and unfathomably influential opening - Jaws didn't pioneer this sort of thing, but it made it almost impossible to stumble across a creature movie or really even a horror film generally that opens in any other way - and deceptively sophisticated. First, and obviously, there is the way Fields cuts between Chrissie and Cassidy, initially just silently demonstrating how far apart they are from each other. Then there is the matter of the attack itself, and of course it is wonderfully tense and horrifying, much of which has to do with Fields's choppy, arrhythmic cutting, and much to do with Spielberg's cunning (and, if the stories are true, semi-abusive) directing. But what I want to call your attention to, is that in all of this crazy, hectic flurry of motion, there is one and only one jump-cut; that is, only one moment at which the editing breaks with strict continuity; it is when the shark first bites Chrissie, a startling and horrifying moment, one that is made all the more jarring for us because of that violence against continuity. It's a simple thing, maybe even an obvious one - but how many movies don't do it? Anyway, it's the very definition of a filmmaking gambit that works even if (especially if) you don't notice it, and this is true of Jaws as a whole; it is the key to Spielberg's entire filmography, really, with its characteristic blend of precise filmmaking mechanics and a showman's desire to appeal to the broadest audience.

But we are not done with that scene yet: there is the occasional punctuation of Chrissie's violent death (it has been compared, several times, to a rape) with Cassidy's increasingly slow and sleepy attempts to get into the water, with the attendant shift in sound from loud to silent (this is a change from the start of the scene, where the land was full of noise and the water mostly silent) and the visual palette changing from greyish-blue and black to brownish-black. Then the last two shots (Cassidy asleep on the beach, the empty ocean with a buoy where Chrissie died) sum up the scene, before an absolutely beautiful dissolve matching the horizon line to the view from our protagonist's house.

Nothing exists in a vacuum, of course, and there are at least five distinct disciplines that all have to work together to make this scene work: the editing, the sound design, the cinematography, the musical score, and the directing and acting. But I have claimed and will stand by that claim, that the editing is something particularly special.

From here, the plot properly begins, and the next 15 minutes demonstrate one of the film's other great triumphs that tends to get ignored in favor of the more obvious (and, to be fair, more important) contributions of Spielberg's direction: Jaws has a really fucking great screenplay. This is a little bit surprising, given that it is adapted from a resolutely adequate potboiler by Peter Benchley, and a whole lot more surprising given that the adaptation was executed by Benchley himself, with assistance from TV comedy writer Carl Gottlieb. Not a prepossessing start, yet what came out of it is one of the most mechanically flawless American screenplays this side of Casablanca: assuredly, it is not idiot-proof in the way that Casablanca is, and without seeing the actual shooting script it's hard to say what Spielberg and even Fields might have done to improve any lapses. But based on the evidence we can see, the writing is pretty damn tremendous. It's one of those films where not a single line of dialogue nor a story beat is wasted; everything serves to either establish character or a situation, frequently both. The first scene with our protagonist, Martin Brody (Roy Scheider) is a perfect example: the information we need to know (he is the chief of police, he is new to Amity Island, he is something of a well-liked alien among the native islanders, he is afraid of water) is dribbled out piecemeal, explained to us with brutal efficiency and sweetened enough that it doesn't feel at all like exposition. Brody's first line is to complain about the sun in his eyes; his wife, Ellen (Lorraine Gary) points out that they bought the house in the fall. Boom, right there we know that they've moved in the last nine months, that Brody is a grumbler, two things that will matter for the whole rest of the movie, and it's established in his very first interaction with another character. That's how everything is explained: his profession and his relationship to the town, the town's reliance on tourism, the effect a killer shark would have on that tourism, and so on and so forth. It's a miracle of concision, and I will not bore you all by going through it piece by piece, but it's an incredible amount of information in very little time.

This makes a lot of sense when one steps back and considers the whole structure of Jaws: in effect, it needs to fit an entire movie in half the running time, for the entire thing is really a two-part narrative consisting of two three-act structures. The first half (actually, slightly more: 65 minutes of a 124-minute film) is the messy character-driven thriller of one man's attempt to save his town from its own stupidity, and in order to present this story in slightly more than an hour, it has to move quickly. I had never, in all the many times I've watched this film, actually paid attention to the timing of events throughout, but it is a far swifter narrative than I'd have guessed; the death of the Kintner boy, the big woomph! moment of the first third, comes all of 16 minutes into the movie, by which point virtually all of the conflicts that will define the first 65 minutes have been established.

At the same time, the first half has to not only function on its own terms of establishing a threat and building up a community that is reasonable and believable enough that we will feel anguished when it is threatened, but also to establish a foundation for the second half. It's no secret that the second part of Jaws is, on the whole, better than the first, which says more about the second part; it is tremendous filmaking in every regard, essentially a three-man play taking place entirely in one location, simultaneously a man vs. nature adventure as well as being a character drama about three incompatible people being thrust into a situation where they must work together in despite of their considerable differences of temperament and tone (it is one of the great glories of the film that at some point in the last 50 minutes, there is every possible iteration of two-against-one amongst the three used to propel some moment of conflict or another).

Incidentally, it is this point that has always made me regret when people label Jaws as the big honkin' blockbuster that ruined the New Hollywood Cinema and began the beginning of the long slow death of American filmmaking. For all it's B-movie trappings, I have, for one, always regarded Jaws as being a natural part of the New Hollywood movement in a way that e.g. Star Wars is not, for it is at heart a character study with class warfare overtones, nestled inside a shark-hunting adventure. No, it is not the most sophisticated character study of the 1970s. But I defy anyone to name a single big effects-driven blockbuster made anytime after 1975 that has even one character as sharply-drawn and richly played as the three heroes of Jaws; or to name another huge summer movie where the consensus pick for its best scene is a lengthy monologue captured in great long takes.

Nor should we begrudge the film its financial success: truth be told, it basically needed to be the first $100 million film of all time in order for Spielberg to have any career at all following. Not literally, but after going to massively far over-budget and over-schedule, a little hit wouldn't have done it; it had to be a great huge hit or the relatively green filmmaker would be persona non grata, and the future evidence of his career leads me to regard that as a bad thing, although I do happen to regard Jaws as his directorial peak, even if that is partially the result of happy accident (shark that didn't work, invisible menace, etc. - you surely don't need to hear that story again from me).

I was, however, talking about how wonderfully the film sets up its second half: the initial appearance of grizzled fisherman Quint (Robert Shaw), in what is effectively a first-act appearance of a human Chekhov's gun; the scene with the idiot shark hunters in which the floating pier stands in for the shark, foreshadowing the use of the yellow barrels later on; marine biologist Matt Hooper (Richard Dreyfuss) telling a story of how a shark destroyed his boat. And of course, the film establishes the characters in vivid detail, all the way up to the final conflict with the big 25-foot rubber doll that we thankfully only see in bits and pieces, the evident fakeness of which isn't enough to derail a film that has completely won us over by that point - I think it is sometimes overlooked that not only does the absence of the shark in the first hour work because the unseen is scarier than the seen, but because the seen in this case looks really dumb, and the film needed us on its side before it asked us to suspend our disbelief on that grey thing being a shark.

Anyway, as I was saying, the vivid character details: the reason Jaws is still better than any other monster movie or summer blockbuster ever made. Amity is a real place, with real people who even in one little moment seem to have a whole life somewhere offscreen; meanwhile, our main characters all have real honest-to-God presence and depth, some of which comes in very unexpected ways - for example, the godawful powder blue jacket with little white anchors worn by the mayor (Murray Hamilton), a marvelous touch of characterisation through costuming; or the incredible dinner table scene between Brody and his youngest son. It helps that they're impressively played, with some really nice touches. Even as broad a character as Quint has subtle moments (thank God for Shaw's performance, without which the character might have slid into cartoon excess): his little glances and facial twitches when nobody but the camera is looking - at one point, he frowns a little when Brody reluctantly sips at Quint's homemade alcohol, and it's as great a character moment as film can possess.

Anyhow: Jaws. It's a good 'un. And I have barely touched upon John William's incredible score, horns and bass strings creating a throbbing sense of menace: the main theme is clearly a response to Bernard Herrmann's famous stabbing strings in Psycho, and it is beyond question the single finest piece of horror movie music in between that film and Halloween. Any composer would be proud to call it his best work - there is one cue, during the final day's chase, where it gets a bit too sprightly for to mood of the moment, but that is the single misstep - given the incredible run of scores he wrote between 1977 and 1983, it's not much more than a warm-up, though it's still one of the chief reasons the film builds tension as well as it does.

Nor did I so much as mention Bill Butler, a cinematographer whose career is otherwise of little note - he'd eventually shoot Anaconda, so that's something - though he and Spielberg were responsible here for the very best ship-bound camerawork in film history, turning a chaotic shoot on the water into some of the smoothest, most rhythmic shots of the ocean that you will ever see no matter how many boat movies you watch and no matter who tries to make them in the future.

But that's the hell of Jaws: it is a perfect movie. Some may complain about its relative lack of thematic depth; to hell with them. It's deep enough to have a real sense of personality, and not so deep that it ceases to be an amazingly tight monster thriller, a genre film of the absolute highest order with intelligence and pretty much the best craftsmanship that ever went into the making of a film that could honestly be tagged with the label of "horror". It is, simply put, one of the absolute masterpieces of populist cinema, and worthy of more respect and love than I or any one writer could ever send its way.

Reviews in this series

Jaws (Spielberg, 1975)

Jaws 2 (Szwarc, 1978)

Jaws 3-D (Alves, 1983)

Jaws: The Revenge (Sargent, 1987)