Everything begins and ends at the exactly right time and place

A review requested by Jonny Mugwump, with thanks to supporting Alternate Ending as a donor through Patreon.

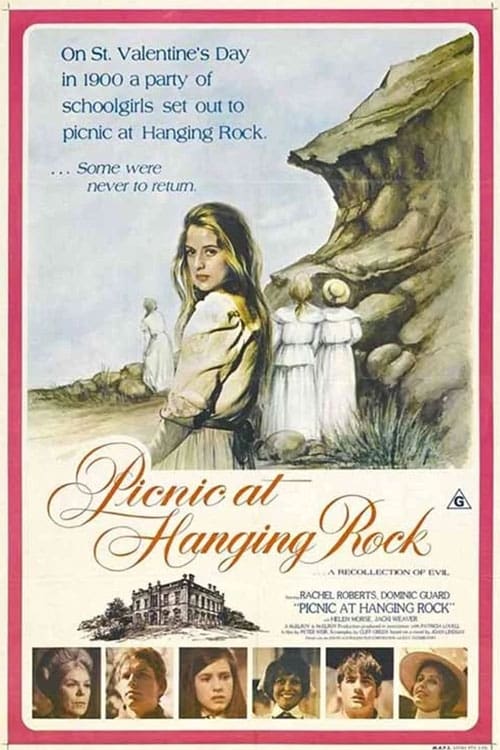

At the risk of immediately sounding like the absolute dumbest motherfucker imaginable, I think there's a very good reason it's called Picnic at Hanging Rock, not Disappearance at Hanging Rock. Along with L'avventura, this is one of cinema's greatest anti-mysteries, a story that has told us before begin watching it not to bother expecting to come together in any conventionally satisfying way. The card that opens the film tells us as much: "On Saturday 14th February 1900 a party of schoolgirls from Appleyard College picnicked at Hanging Rock near Mt. Macedon in the state of Victoria. During the afternoon several members of the party disappeared without trace... [uncanny lack of commas and other grammatically irregularities in the original]" That summarises the first two-fifths of the story, and rather bluntly implies what we can expect to happen in the remaining three-fifths: not a resolution to where the missing girls went, at any rate. It's the film's way of replicating the more coy, and I would say much more sardonic, preface that Joan Lindsay provided to her 1967 novel, the source for Cliff Green's screenplay: "Whether Picnic at Hanging Rock is fact or fiction, my readers must decide for themselves. As the fateful picnic took place in the year nineteen hundred, and all the characters who appear in this book are long since dead, it hardly seems important". So there you go: one story, two media, the same invitation - if you're trying to figure this out, you're doing it wrong.

So back to my incredibly facile opening observation - and please note, I'm not sure how one is supposed to discuss Picnic at Hanging Rock without being facile. It's a a work whose metaphor and symbolism are so right there that describing them using a crude tool like the written word can't help but make the movie sound blunt and clumsily Freudian. Yet in the moment of watching, those symbols are so glancing, so abstract, set into the film with such gauzy, fragile delicacy that it feels like you might break the movie if you looked straight at it, let alone if you tried to describe it. Anyway, by leading with the picnic rather than the disappearance, I think the title, in any medium, is trying to gently guide our attention: the picnic, and not the mystery or how any of the characters react to it, is the important part.

And what, pray tell, is "the picnic"? As noted, it takes place on St. Valentine's Day, 14 February 1900, at the base of Hanging Rock, a huge volcanic outcropping in southeast Australia. It's the last full year of the Victorian era, and the last year before the six British colonies on the continent of Australia joined together as federation of states comprising an independent nation. None of these chronological facts seem remotely coincidental: among the most obvious things to say that the story is "about", it is "about" the blundering crudeness of the British Empire, with its insistence on exporting the rigid behaviors and hierarchies and traditions of 19th Century England to every continent on God's earth, securing in the swaggering confidence that Victorian England was the ultimate form of humanity. Setting this story right on the brink of Victorian England plonking to a close, and Australia managing to wrest itself out of England's political shadow, are both signs that the prim & proper behavior we'll be witnessing for the film's 106 minutes (in the shorter director's cut prepared by Peter Weir many years after the film's 1975 debut; this cut has, I believe, fully replaced the 115-minute original cut in basically every extant commercial context) are the dying carcass of an old world, good riddance to it. And as for setting it on Valentine's Day - which, as a gentle reminder to my fellow Northern Hemisphereans, is in the heat of late summer in Australia - what better day than the international celebration of erotic love to set a story about the metaphorical eruption of adolescent girls' repressed sexual desire knocking the stuffing out of Victorian prudery so hard that it rewires the rules of physics? Which gets us back to that clumsy Freudianism I was trying to avoid. But the thing is, you cannot talk Picnic at Hanging Rock without at least taking a stroll past unambiguous Freudian imagery; the big phallic stone pillars of the Hanging Rock site, the yonic gash left in a heart-shaped cake, the cloud of euphemism every time the word "intact" is said out loud, all that good stuff. The disappearance is about symbolically escaping restrictive sexual mores - whether into death and oblivion or into self-actualised liberation is immaterial relative to the escape itself. I don't even think this is me interpreting the film, I think it's just a fact about what the film is. My baseline impatience with Freudian symbolism is quite entirely beside the point.

So that gives us two big things that the film is "about" at the script level; a third thing if you want to pragmatically say that it's "about" the narrative progression the disappearance followed by the investigation, and what happens to the named characters across the film's running time, which is definitely the least-sastifying way to watch Picnic at Hanging Rock that I can imagine selecting. And then there's what the film is "about" as a work of audio-visual art, bringing that script to life, which is kind of another thing altogether. The Freudianism is encoded into the visuals enough that you can't fully disentangle style and theme on that front, I concede. But mostly, what the film is about as a film is moodily sinking into something thoroughly unknowable, and maybe not even fully articulable outside of the stylistic methods the film itself employs. This is part of why despite having such, I hesitate to use the word, "obvious" themes, Picnic at Hanging Rock ends up feeling so opaque and challenging to deal with. It is, in large part, about pressing us into unnervingly close contact with something that isn't human, though fucked if I know what it is. Maybe not even a thing as such, maybe just a state of being that we're not meant to interact with. You could be very blunt and call this "the Australian wilderness, shame on those Brits for trying to tame it", and you wouldn't be wrong, but unlike Weir's other great phantasmagorical thriller about Europeans fundamentally not grasping the spiritual energies of the Australian continent, 1977's The Last Wave, I don't really know that Picnic at Hanging Rock especially cares about the Australian landmass per se at all - other than one reference to unseen Aboriginal trackers helping to investigate the disappearance, there's not so much as a glance at the cultural traditions on the continent present before Europeans arrived there. This is something different than that.

It's this stark sense of there being something fundamentally outside-of-the-human, beyond our concepts of good or bad, benign or malefic, but implacable and insatiable and dangerous, that makes me very comfortable calling Picnic at Hanging Rock one of the greatest horror movies ever made despite it being a fairly open question whether the word "horror" really applies to the film at all. Nothing here is, or is trying to be, "scary". It's more weird, in the Weird Tales sense. But even the lack of strong genre cues is sort of what makes it feel so incomprehensible, and the lack of comprehension is what fuels the sense of a world that has thrown out all the rules we think keep us safe, which is its own sort of terror. This is horrifying in the truly Lovecraftian sense: horror is not the presence of nasty monsters who will kill and eat you, it is being confronted with things so far outside of our framework that we can't even understand what's dangerous about them.

All this, I think, is the film's mood. How the film arrives at that mood gets us to Weir's excellent directing and the strong work of an extremely gifted crew and cast. Picnic at Hanging Rock, independently of anything else, has long had the reputation outside of Australia as being the film that basically invented the Australian film industry, which is blatantly untrue of course. It's not even Weir's own first feature. It is, though, fairly incontestably the film that demonstrated Australian cinema's ability to thrive on a global scale, the first Australian film of significant note that was distributed internationally to great acclaim, and much of this is because it combines the very best elements of an emerging and a mature industry. From a mature industry: people who know what they're doing and how to do it well. From an emerging industry: a sense of rules-free openness, a readiness to try things out that are very strange and even broken, but which work so tremendously well that they end up forming their own new lexicon. As Picnic at Hanging Rock did: especially in its use of sound, this was an early (could even be the earliest - I haven't seen any precursors) example of a new way of evoking the unknowable through electronic gashes in the soundtrack. Not quite electronic drones, not quite music, but something sinister hovering "outside" of the film in some way. And since I'm touching on the sound, might as well touch on the bizarre patchwork quilt of music, including traditional Romanian panpipe music performed by Gheorghe Zamfir, an ethereal but grating melodic line that's somehow much more conventionally beautiful than the contributions made by Australia's own Bruce Smeaton, weird rolling pieces in a not-quite-right key with bizarre meter that sounds like traditional European symphonic music got buried in a cave for a millennium, discovered by aliens, and reinterpreted by beings who knew none of the "rules".

I even wonder if sound might be the main way that the film creates its strange, unpredictable feeling, though the star of the show is pretty obviously the cinematography, the first collaboration between Weir and his longtime go-to guy Russell Boyd. The strategy is as simple as possible: diffuse the absolute hell out of everything in the first part, and then have everything else nice and sharp and clear (the medium of diffusion, it is said, was a bridal veil laid over the lens, which could just be simple DIY ingenuity, but it's so neat to have that be a technique used in a film about the myth of feminine sexual innocence and the awakening of libidinal desire that I sort of refuse to believe it's actually true). It's not really complicated at all when you just stare at it - like so much of the movie, really - but it yields such exceptionally great results that it feels like it must be something radical and groundbreaking. Possibly that's just because it means that all of the early scenes really do feel almost like they're not even movie footage, more like we've slipped into a world where oil paintings became cinema: the shots in exterior sunlight, of which there are many, are so soft and free from definite shapes, rendering colors almost more like pointillist impressions of hue rather than the hues themselves. And it's photographic reality, so in theory it can't do that, but there it is onscreen anyway. At any rate, the opening of the film is cloudy, dreamlike: it feels like a world inhabited exclusively by ghosts. And then the picnickers disappear, and the diffusion goes away, and the remainder of the film is bright, sharp, and hot, the sun baking the world into a brown shell.

It has a pretty distinctive effect on the impact the film makes: if the opening is a strange, alien journey into nature, the second half (more than half, but I hope you take my point) feels like the confused moment of waking up into the daytime world, raw and disoriented. What remains of the film is like the scrambling effort to remember a dream as it's fading, feeling increasingly frustrated as that simply refuses to happen. Which loops us all the way back to the basic scenario: the film is a quest for answers that won't come and probably don't exist, and certain level of unsatisfied desperation is basically what the film is about. Or it's about re-burying the repressed sexual id. Or it's about having the good fortune to survive a brush with something beyond humanity and having the godawful foolishness to want that something to come back. In other words, it's kind of inexhaustible, a brilliantly ambiguous film about ambiguity.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

At the risk of immediately sounding like the absolute dumbest motherfucker imaginable, I think there's a very good reason it's called Picnic at Hanging Rock, not Disappearance at Hanging Rock. Along with L'avventura, this is one of cinema's greatest anti-mysteries, a story that has told us before begin watching it not to bother expecting to come together in any conventionally satisfying way. The card that opens the film tells us as much: "On Saturday 14th February 1900 a party of schoolgirls from Appleyard College picnicked at Hanging Rock near Mt. Macedon in the state of Victoria. During the afternoon several members of the party disappeared without trace... [uncanny lack of commas and other grammatically irregularities in the original]" That summarises the first two-fifths of the story, and rather bluntly implies what we can expect to happen in the remaining three-fifths: not a resolution to where the missing girls went, at any rate. It's the film's way of replicating the more coy, and I would say much more sardonic, preface that Joan Lindsay provided to her 1967 novel, the source for Cliff Green's screenplay: "Whether Picnic at Hanging Rock is fact or fiction, my readers must decide for themselves. As the fateful picnic took place in the year nineteen hundred, and all the characters who appear in this book are long since dead, it hardly seems important". So there you go: one story, two media, the same invitation - if you're trying to figure this out, you're doing it wrong.

So back to my incredibly facile opening observation - and please note, I'm not sure how one is supposed to discuss Picnic at Hanging Rock without being facile. It's a a work whose metaphor and symbolism are so right there that describing them using a crude tool like the written word can't help but make the movie sound blunt and clumsily Freudian. Yet in the moment of watching, those symbols are so glancing, so abstract, set into the film with such gauzy, fragile delicacy that it feels like you might break the movie if you looked straight at it, let alone if you tried to describe it. Anyway, by leading with the picnic rather than the disappearance, I think the title, in any medium, is trying to gently guide our attention: the picnic, and not the mystery or how any of the characters react to it, is the important part.

And what, pray tell, is "the picnic"? As noted, it takes place on St. Valentine's Day, 14 February 1900, at the base of Hanging Rock, a huge volcanic outcropping in southeast Australia. It's the last full year of the Victorian era, and the last year before the six British colonies on the continent of Australia joined together as federation of states comprising an independent nation. None of these chronological facts seem remotely coincidental: among the most obvious things to say that the story is "about", it is "about" the blundering crudeness of the British Empire, with its insistence on exporting the rigid behaviors and hierarchies and traditions of 19th Century England to every continent on God's earth, securing in the swaggering confidence that Victorian England was the ultimate form of humanity. Setting this story right on the brink of Victorian England plonking to a close, and Australia managing to wrest itself out of England's political shadow, are both signs that the prim & proper behavior we'll be witnessing for the film's 106 minutes (in the shorter director's cut prepared by Peter Weir many years after the film's 1975 debut; this cut has, I believe, fully replaced the 115-minute original cut in basically every extant commercial context) are the dying carcass of an old world, good riddance to it. And as for setting it on Valentine's Day - which, as a gentle reminder to my fellow Northern Hemisphereans, is in the heat of late summer in Australia - what better day than the international celebration of erotic love to set a story about the metaphorical eruption of adolescent girls' repressed sexual desire knocking the stuffing out of Victorian prudery so hard that it rewires the rules of physics? Which gets us back to that clumsy Freudianism I was trying to avoid. But the thing is, you cannot talk Picnic at Hanging Rock without at least taking a stroll past unambiguous Freudian imagery; the big phallic stone pillars of the Hanging Rock site, the yonic gash left in a heart-shaped cake, the cloud of euphemism every time the word "intact" is said out loud, all that good stuff. The disappearance is about symbolically escaping restrictive sexual mores - whether into death and oblivion or into self-actualised liberation is immaterial relative to the escape itself. I don't even think this is me interpreting the film, I think it's just a fact about what the film is. My baseline impatience with Freudian symbolism is quite entirely beside the point.

So that gives us two big things that the film is "about" at the script level; a third thing if you want to pragmatically say that it's "about" the narrative progression the disappearance followed by the investigation, and what happens to the named characters across the film's running time, which is definitely the least-sastifying way to watch Picnic at Hanging Rock that I can imagine selecting. And then there's what the film is "about" as a work of audio-visual art, bringing that script to life, which is kind of another thing altogether. The Freudianism is encoded into the visuals enough that you can't fully disentangle style and theme on that front, I concede. But mostly, what the film is about as a film is moodily sinking into something thoroughly unknowable, and maybe not even fully articulable outside of the stylistic methods the film itself employs. This is part of why despite having such, I hesitate to use the word, "obvious" themes, Picnic at Hanging Rock ends up feeling so opaque and challenging to deal with. It is, in large part, about pressing us into unnervingly close contact with something that isn't human, though fucked if I know what it is. Maybe not even a thing as such, maybe just a state of being that we're not meant to interact with. You could be very blunt and call this "the Australian wilderness, shame on those Brits for trying to tame it", and you wouldn't be wrong, but unlike Weir's other great phantasmagorical thriller about Europeans fundamentally not grasping the spiritual energies of the Australian continent, 1977's The Last Wave, I don't really know that Picnic at Hanging Rock especially cares about the Australian landmass per se at all - other than one reference to unseen Aboriginal trackers helping to investigate the disappearance, there's not so much as a glance at the cultural traditions on the continent present before Europeans arrived there. This is something different than that.

It's this stark sense of there being something fundamentally outside-of-the-human, beyond our concepts of good or bad, benign or malefic, but implacable and insatiable and dangerous, that makes me very comfortable calling Picnic at Hanging Rock one of the greatest horror movies ever made despite it being a fairly open question whether the word "horror" really applies to the film at all. Nothing here is, or is trying to be, "scary". It's more weird, in the Weird Tales sense. But even the lack of strong genre cues is sort of what makes it feel so incomprehensible, and the lack of comprehension is what fuels the sense of a world that has thrown out all the rules we think keep us safe, which is its own sort of terror. This is horrifying in the truly Lovecraftian sense: horror is not the presence of nasty monsters who will kill and eat you, it is being confronted with things so far outside of our framework that we can't even understand what's dangerous about them.

All this, I think, is the film's mood. How the film arrives at that mood gets us to Weir's excellent directing and the strong work of an extremely gifted crew and cast. Picnic at Hanging Rock, independently of anything else, has long had the reputation outside of Australia as being the film that basically invented the Australian film industry, which is blatantly untrue of course. It's not even Weir's own first feature. It is, though, fairly incontestably the film that demonstrated Australian cinema's ability to thrive on a global scale, the first Australian film of significant note that was distributed internationally to great acclaim, and much of this is because it combines the very best elements of an emerging and a mature industry. From a mature industry: people who know what they're doing and how to do it well. From an emerging industry: a sense of rules-free openness, a readiness to try things out that are very strange and even broken, but which work so tremendously well that they end up forming their own new lexicon. As Picnic at Hanging Rock did: especially in its use of sound, this was an early (could even be the earliest - I haven't seen any precursors) example of a new way of evoking the unknowable through electronic gashes in the soundtrack. Not quite electronic drones, not quite music, but something sinister hovering "outside" of the film in some way. And since I'm touching on the sound, might as well touch on the bizarre patchwork quilt of music, including traditional Romanian panpipe music performed by Gheorghe Zamfir, an ethereal but grating melodic line that's somehow much more conventionally beautiful than the contributions made by Australia's own Bruce Smeaton, weird rolling pieces in a not-quite-right key with bizarre meter that sounds like traditional European symphonic music got buried in a cave for a millennium, discovered by aliens, and reinterpreted by beings who knew none of the "rules".

I even wonder if sound might be the main way that the film creates its strange, unpredictable feeling, though the star of the show is pretty obviously the cinematography, the first collaboration between Weir and his longtime go-to guy Russell Boyd. The strategy is as simple as possible: diffuse the absolute hell out of everything in the first part, and then have everything else nice and sharp and clear (the medium of diffusion, it is said, was a bridal veil laid over the lens, which could just be simple DIY ingenuity, but it's so neat to have that be a technique used in a film about the myth of feminine sexual innocence and the awakening of libidinal desire that I sort of refuse to believe it's actually true). It's not really complicated at all when you just stare at it - like so much of the movie, really - but it yields such exceptionally great results that it feels like it must be something radical and groundbreaking. Possibly that's just because it means that all of the early scenes really do feel almost like they're not even movie footage, more like we've slipped into a world where oil paintings became cinema: the shots in exterior sunlight, of which there are many, are so soft and free from definite shapes, rendering colors almost more like pointillist impressions of hue rather than the hues themselves. And it's photographic reality, so in theory it can't do that, but there it is onscreen anyway. At any rate, the opening of the film is cloudy, dreamlike: it feels like a world inhabited exclusively by ghosts. And then the picnickers disappear, and the diffusion goes away, and the remainder of the film is bright, sharp, and hot, the sun baking the world into a brown shell.

It has a pretty distinctive effect on the impact the film makes: if the opening is a strange, alien journey into nature, the second half (more than half, but I hope you take my point) feels like the confused moment of waking up into the daytime world, raw and disoriented. What remains of the film is like the scrambling effort to remember a dream as it's fading, feeling increasingly frustrated as that simply refuses to happen. Which loops us all the way back to the basic scenario: the film is a quest for answers that won't come and probably don't exist, and certain level of unsatisfied desperation is basically what the film is about. Or it's about re-burying the repressed sexual id. Or it's about having the good fortune to survive a brush with something beyond humanity and having the godawful foolishness to want that something to come back. In other words, it's kind of inexhaustible, a brilliantly ambiguous film about ambiguity.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.