Witch way to London

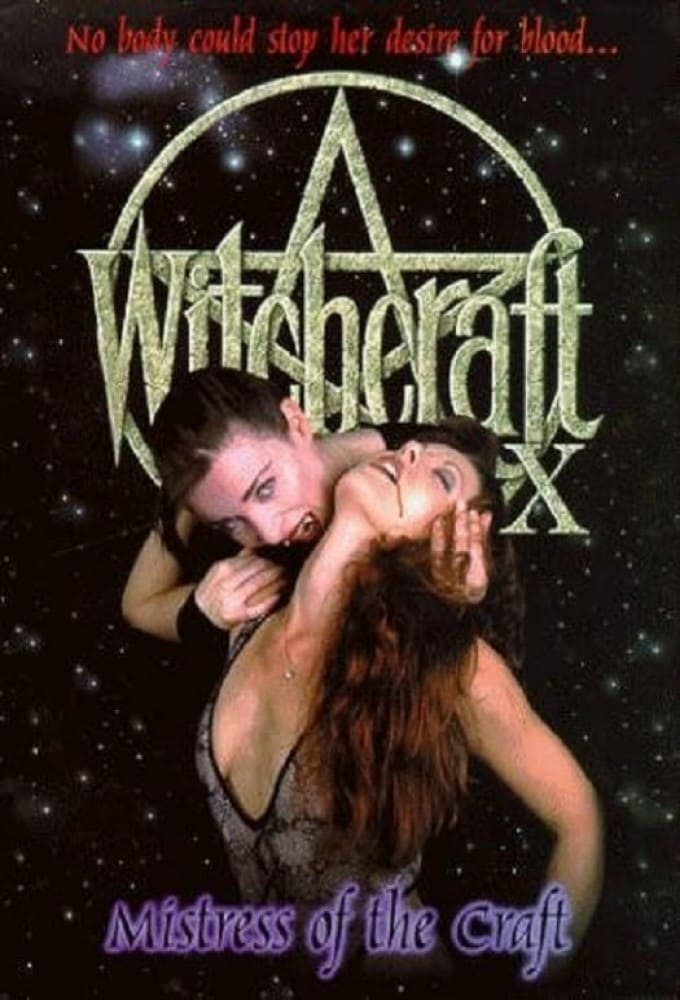

In discussing any long-running series that doesn't exactly swing from pole to pole, qualitywise, one of the trickiest parts in reviewing the individual entries can be figuring out where to start: what specifically makes this film different from all of those films? Happily, then, Witchcraft X: Mistress of the Craft - which premiered in 1998 but wasn't released to video until 1999, which means this was the first break in a perfect "one per year" pattern stretching all the back to 1991's Witchcraft III: The Kiss of Death - has quite possibly the single most important thing to discuss that any of these movies have provided since the first Witchcraft started the series off. There's literally only one reason to care about the Witchcraft pictures, after all: it is, infamously, the longest-running American* horror movie series in history, by number of entries. And Mistress of the Craft is the film with which it took that title: in 1998 (and in 1999, for that matter), the most recent entry in the Friday the 13th series was 1993's Jason Goes to Hell: The Final Friday, the ninth one. And as far as I can tell, Friday the 13th was the previous record-holder for most entries in a single horror series.† So here we are: the tie has been broken, and Witchcraft has now achieved the only point of meritorious distinction it will ever know.

The film that passed this milestone is decidedly unworthy of the honor; in point of fact, Mistress of the Craft is the worst movie in the series thus far. Not by any extreme margin, but it has the distinction of being obviously produced for pennies, above and beyond the don't-give-a-shit amateurism that has been a constant companion to this series. I don't think I can come up with a better summary moment of Mistress of the Craft than when Detective Lucy Lutz (Stephanie Beaton) of the LAPD wanders into INTERPOL Agent Chris Dixon's (Sean Harry) office - or maybe it's his boss's office, I don't remember - and his bookshelf is full of a random assortment of photographs that clearly showed up because the set decoration team was told "get photos" and did not have any direction as to what function those photos would serve, nor an inclination to figure it out on their own. So we get a young man looking very serious as he stands next to a tree sitting right next to a black-and-white glamour shot of a model that very obviously came with the frame, and both of these have been situated in the compositions so they seem to be at least as crucial to the story as Lutz or Dixon themselves.

In short: this doesn't take place in a world, it takes place in the production offices of, I presume, Armadillo Films, which have been redressed using the smallest number of props possible, so that it will take the least amount of effort necessary to undo the production design once the camera crew leaves. The film was shot in London, and it takes place there, but this was not so that the filmmakers (under the general command of writer-director Elisar Cabrera) could take advantage of the city's beautiful locations. Nor even its ugly ones. While the average Witchcraft picture at least takes a walking tour of the couple of square miles of Los Angeles right outside of Vista Street Entertainment's headquarters, Mistress of the Craft is set almost entirely within an endless chain of hallways and white rooms, occasionally going up to the roof to look at a part of the London skyline that doesn't have any of the famous buildings in it.

Lutz arrives in this empty, ugly world because INTERPOL's Bureau 17, out of London, has recently captured Hyde (Kerry Knowlton), a California-based Satanist who'd been causing some trouble for her and partner Det. Garner, as well as warlock lawyer Will Spanner - she mentions both of them by name early on, and it's almost genuinely sad how clearly Mistress of the Craft wants us to be proud of it for making a clear connection between this and the rest of the franchise. She's just looking to pick up Hyde and head home, but he's already caught the eye of another malevolent, paranormal force: a coven of vampire witches (somehow, there are always exactly three of them, no matter how many we watch die) led by Raven (Eileen Daly) has decided that Hyde's direct line to Satan will be a good fit for their own evil desires. Luckily for the out-of-their element Lutz and Dixon, Raven has been under the watchful eye of Celeste Sheridan (Wendy Cooper), a Bureau 17 agent, but also a powerful white witch - the Mistress of the Craft who gives this film its unusually well-motivated subtitle. And she's more than a match for the vampires, in her turquoise pleather cape and high heels that make her look like a Silver Age comic book hero who has inadvertently wandered into this sleazy horror-lite universe. So much of a match, in fact, that we never need to bother worrying about whether the good guys are going to win or not, so Cabrera is able to dedicate plenty of time to watching people get naked and have sex.

Or is it plenty of time? The one constant... "compliment" isn't a word I like, but we'll run with it, that I've had for this franchise is that at least it's trashily pornographic enough to remain dully diverting. Mistress of the Craft backs off on that - not all the way, mind you. It's still pretty crass, and indeed this is the first time since she became a woman that Lutz has taken off her top in one of these films, so we're still comfortably in the territory of greasy skin flicks. Also, Mistress of the Craft ups the ante twice over, once by having two of the vampires (all of whom are bisexual) seduce a male victim simultaneously, giving us our first threesome in the series, and also including a sequence that crosscuts between three different sex scenes, at least if we include Lutz splashing around in a bubble bath a "sex scene". So plenty of sordid content to go 'round, but it feels like the filmmakers were trying to hit a quota, and the cross-cutting meant that they could hit it much earlier. And so we get, by far, the most sexless Witchcraft in several entries.

That's not inherently a problem. Almost all of my favorite films ever made are non-pornographic. The issue is that the Witchcraft pictures have never been good at literally anything other than softcore pornography (and indeed, they are not always good at that, as the viscerally revolting opening sequence of Witchcraft 7: Judg[e]ment Hour reminds us). Scaling back on the most prurient, exploitative elements hardly feels like it's playing to the series' core competencies, in other words, especially since Mistress of the Craft is also the one where the threadbare production values hit rock bottom. It's a film that leaves us with nothing: not even the meagerest pretense of being adequate as horror, not sex, not even really a narrative structure, since it's so clear that Celeste is an overmatched foe for Raven and Hyde, even put together.

Pretty much the solitary nice thing I have to say is that Daly, and only Daly, seems keenly aware of the film she's in, and she gives one of the best performances of overwrought kitschy villainy that the series has seen yet. A great scenery-chewing villain has been almost enough to salvage the experience of earlier Witchcrafts into so-bad-it's-good territory, and Daly can't manage that; she's got too much to compensate for, both in the silted "reading from cue cards" quality of all her co-stars, and in the insultingly lazy scale of the production. Even the sound mixing feels like it was conducted in somebody's bathtub. With the water running. But at least she's there to make for a few giggle-worthy moments, without which Mistress of the Craft would be virtually unendurable.

Reviews in this series

Witchcraft (Spera, 1988)

Witchcraft II: The Temptress (Woods, 1989)

Witchcraft III: The Kiss of Death ("Tillmans" [Feldman], 1991)

Witchcraft IV: The Virgin Heart (Merendino, 1992)

Witchcraft V: Dance with the Devil (Hsu, 1993)

Witchcraft 666: The Devil's Mistress (Davis, 1994)

Witchcraft 7: Judgement Hour (Girard, 1995)

Witchcraft VIII: Salem's Ghost (Barmettler, 1996)

Witchcraft IX: Bitter Flesh (Girard, 1997)

Witchcraft X: Mistress of the Craft (Cabrera, 1998)

Witchcraft XI: Sisters in Blood (Ford, 2000)

Witchcraft XII: In the Lair of the Serpent (Sykes, 2004)

Witchcraft 13: Blood of the Chosen (House, 2008)

Witchcraft XIV: Angel of Death (Palmieri, 2016)

Witchcraft XV: Blood Rose (Palmieri, 2016)

Witchcraft XVI: Hollywood Coven (Palmieri, 2016)

*There are 20 entries in Hong Kong's Troublesome Night franchise, all but one of them produced between 1997 and 2003. They are all anthologies of loosely-connected stories, and to my knowledge there are no connections between the different features at all, meaning that this is perhaps more accurately thought of as a brand name than as a series per se.

†This matter is complicated by the interconnected films of Universal's '30s and '40s monster universe. Counting every Dracula, Frankenstein, and Wolf Man vehicle, ending with 1945's House of Dracula, we get to eleven entries, meaning that it wouldn't be until 2004's Witchcraft XII: In the Lair of the Serpent that our current subject comes to its moment in the sun. But the Universal films were only turned into a series midway through, and even then I think there's an argument to be made that at least some of the Dracula films simply aren't really part of that series, especially 1943's Son of Dracula.

The film that passed this milestone is decidedly unworthy of the honor; in point of fact, Mistress of the Craft is the worst movie in the series thus far. Not by any extreme margin, but it has the distinction of being obviously produced for pennies, above and beyond the don't-give-a-shit amateurism that has been a constant companion to this series. I don't think I can come up with a better summary moment of Mistress of the Craft than when Detective Lucy Lutz (Stephanie Beaton) of the LAPD wanders into INTERPOL Agent Chris Dixon's (Sean Harry) office - or maybe it's his boss's office, I don't remember - and his bookshelf is full of a random assortment of photographs that clearly showed up because the set decoration team was told "get photos" and did not have any direction as to what function those photos would serve, nor an inclination to figure it out on their own. So we get a young man looking very serious as he stands next to a tree sitting right next to a black-and-white glamour shot of a model that very obviously came with the frame, and both of these have been situated in the compositions so they seem to be at least as crucial to the story as Lutz or Dixon themselves.

In short: this doesn't take place in a world, it takes place in the production offices of, I presume, Armadillo Films, which have been redressed using the smallest number of props possible, so that it will take the least amount of effort necessary to undo the production design once the camera crew leaves. The film was shot in London, and it takes place there, but this was not so that the filmmakers (under the general command of writer-director Elisar Cabrera) could take advantage of the city's beautiful locations. Nor even its ugly ones. While the average Witchcraft picture at least takes a walking tour of the couple of square miles of Los Angeles right outside of Vista Street Entertainment's headquarters, Mistress of the Craft is set almost entirely within an endless chain of hallways and white rooms, occasionally going up to the roof to look at a part of the London skyline that doesn't have any of the famous buildings in it.

Lutz arrives in this empty, ugly world because INTERPOL's Bureau 17, out of London, has recently captured Hyde (Kerry Knowlton), a California-based Satanist who'd been causing some trouble for her and partner Det. Garner, as well as warlock lawyer Will Spanner - she mentions both of them by name early on, and it's almost genuinely sad how clearly Mistress of the Craft wants us to be proud of it for making a clear connection between this and the rest of the franchise. She's just looking to pick up Hyde and head home, but he's already caught the eye of another malevolent, paranormal force: a coven of vampire witches (somehow, there are always exactly three of them, no matter how many we watch die) led by Raven (Eileen Daly) has decided that Hyde's direct line to Satan will be a good fit for their own evil desires. Luckily for the out-of-their element Lutz and Dixon, Raven has been under the watchful eye of Celeste Sheridan (Wendy Cooper), a Bureau 17 agent, but also a powerful white witch - the Mistress of the Craft who gives this film its unusually well-motivated subtitle. And she's more than a match for the vampires, in her turquoise pleather cape and high heels that make her look like a Silver Age comic book hero who has inadvertently wandered into this sleazy horror-lite universe. So much of a match, in fact, that we never need to bother worrying about whether the good guys are going to win or not, so Cabrera is able to dedicate plenty of time to watching people get naked and have sex.

Or is it plenty of time? The one constant... "compliment" isn't a word I like, but we'll run with it, that I've had for this franchise is that at least it's trashily pornographic enough to remain dully diverting. Mistress of the Craft backs off on that - not all the way, mind you. It's still pretty crass, and indeed this is the first time since she became a woman that Lutz has taken off her top in one of these films, so we're still comfortably in the territory of greasy skin flicks. Also, Mistress of the Craft ups the ante twice over, once by having two of the vampires (all of whom are bisexual) seduce a male victim simultaneously, giving us our first threesome in the series, and also including a sequence that crosscuts between three different sex scenes, at least if we include Lutz splashing around in a bubble bath a "sex scene". So plenty of sordid content to go 'round, but it feels like the filmmakers were trying to hit a quota, and the cross-cutting meant that they could hit it much earlier. And so we get, by far, the most sexless Witchcraft in several entries.

That's not inherently a problem. Almost all of my favorite films ever made are non-pornographic. The issue is that the Witchcraft pictures have never been good at literally anything other than softcore pornography (and indeed, they are not always good at that, as the viscerally revolting opening sequence of Witchcraft 7: Judg[e]ment Hour reminds us). Scaling back on the most prurient, exploitative elements hardly feels like it's playing to the series' core competencies, in other words, especially since Mistress of the Craft is also the one where the threadbare production values hit rock bottom. It's a film that leaves us with nothing: not even the meagerest pretense of being adequate as horror, not sex, not even really a narrative structure, since it's so clear that Celeste is an overmatched foe for Raven and Hyde, even put together.

Pretty much the solitary nice thing I have to say is that Daly, and only Daly, seems keenly aware of the film she's in, and she gives one of the best performances of overwrought kitschy villainy that the series has seen yet. A great scenery-chewing villain has been almost enough to salvage the experience of earlier Witchcrafts into so-bad-it's-good territory, and Daly can't manage that; she's got too much to compensate for, both in the silted "reading from cue cards" quality of all her co-stars, and in the insultingly lazy scale of the production. Even the sound mixing feels like it was conducted in somebody's bathtub. With the water running. But at least she's there to make for a few giggle-worthy moments, without which Mistress of the Craft would be virtually unendurable.

Reviews in this series

Witchcraft (Spera, 1988)

Witchcraft II: The Temptress (Woods, 1989)

Witchcraft III: The Kiss of Death ("Tillmans" [Feldman], 1991)

Witchcraft IV: The Virgin Heart (Merendino, 1992)

Witchcraft V: Dance with the Devil (Hsu, 1993)

Witchcraft 666: The Devil's Mistress (Davis, 1994)

Witchcraft 7: Judgement Hour (Girard, 1995)

Witchcraft VIII: Salem's Ghost (Barmettler, 1996)

Witchcraft IX: Bitter Flesh (Girard, 1997)

Witchcraft X: Mistress of the Craft (Cabrera, 1998)

Witchcraft XI: Sisters in Blood (Ford, 2000)

Witchcraft XII: In the Lair of the Serpent (Sykes, 2004)

Witchcraft 13: Blood of the Chosen (House, 2008)

Witchcraft XIV: Angel of Death (Palmieri, 2016)

Witchcraft XV: Blood Rose (Palmieri, 2016)

Witchcraft XVI: Hollywood Coven (Palmieri, 2016)

*There are 20 entries in Hong Kong's Troublesome Night franchise, all but one of them produced between 1997 and 2003. They are all anthologies of loosely-connected stories, and to my knowledge there are no connections between the different features at all, meaning that this is perhaps more accurately thought of as a brand name than as a series per se.

†This matter is complicated by the interconnected films of Universal's '30s and '40s monster universe. Counting every Dracula, Frankenstein, and Wolf Man vehicle, ending with 1945's House of Dracula, we get to eleven entries, meaning that it wouldn't be until 2004's Witchcraft XII: In the Lair of the Serpent that our current subject comes to its moment in the sun. But the Universal films were only turned into a series midway through, and even then I think there's an argument to be made that at least some of the Dracula films simply aren't really part of that series, especially 1943's Son of Dracula.