Amicus Horror: Terrible things in store

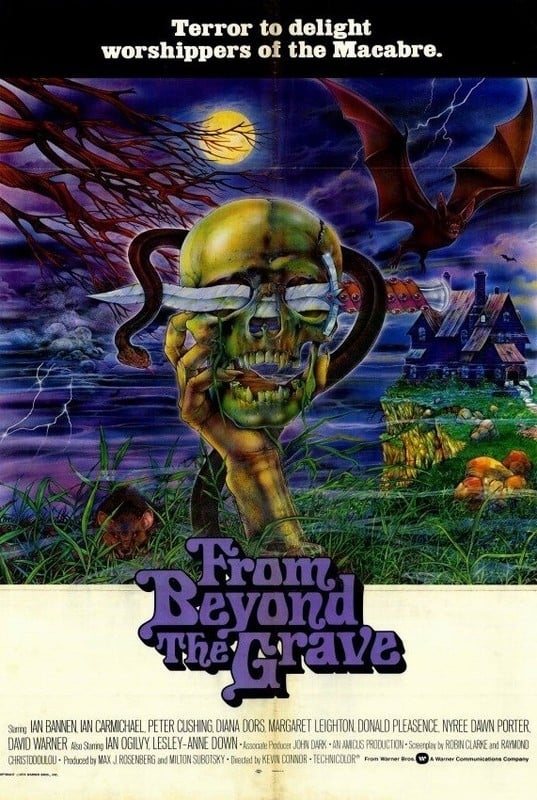

It is with a distinct tinge of melancholy that I welcome From Beyond the Grave to the pages of Alternate Ending. For with this 1974 release, we arrive at the seventh and final "portmanteau" film released by Amicus Productions, the little British horror studio that was, in '74, just about to abandon the genre (the company released two more horror films in the same year, before switching over to a trilogy of adventure movies as a last-ditch attempt to remain solvent during a very rough time for British film production). Happily, From Beyond the Grave, which capped off a run including some of the best-loved horror anthologies ever made, ends things on a high note. While the absence of any individual segment as perfect as Joan Collins facing down a killer Santa Claus or Peter Cushing playing a nice old man extracting bloody revenge in Tales from the Crypt, from 1972, makes it impossible for me to declare that this is the very best of the portmanteau films, it's pretty damn close. While this doesn't quite hit the highest heights of Tales from the Crypt, its relative weak points are stronger; its four stories are of remarkably even quality, and the closest any of them has to a flaw is that the fourth is a bit insubstantial, comparatively speaking. But even this turns out have a good reason behind it.

The unifying theme of the film this time around is the work of Ronald Chetwynd-Hayes, a beloved author of ghost stories, and while I have no exposure to his work outside of this movie, if this is in any way representative, I can definitely see the appeal. Unlike pretty much all of the other Amicus portmanteau films up to this point, the stories in From Beyond the Grave don't build up to ironic endings in which the protagonists' flaws karmically manifest in their comeuppance; they're just quick little yarns about spooky shit happening sort of at random.

Karma is still involved, and it comes in the form of the framing narrative, which is awfully clever and thoughtful, though it's much more insubstantial than I might have liked, given that this the only place where we get any Cushing this time around. He's playing the proprietor of Temptations, Limited, an overstuffed curiosity and antique shop on a quiet side street, and we know right from the start that something mysterious is up with it, because this side street somehow magically appears during a very well-hidden cut during a series of tracking shots through an old rural churchyard. Also because it is named "Temptations, Limited". Over the course of the movie, four different men show up at the store, and find themselves drawn to a particular object; they acquire the object through somewhat shady means, and that's when the curse activates. As payment for trying to cheat the amiable old man (or trickster demon, as the case might be), something horrible happens to them.

The first customer is Edward Charlton (David Warner), an antiques expert who wants a lavish old mirror that comes with a too-steep £250 price tag. Swiftly and decisively he lies to the proprietor that it's obviously a replica, and gets the cost slashed down to £25, and takes it home, where he proudly displays it over the dining table. At a party, one of his friends suggests that it looks like the perfect mirror for a séance, and so everybody playfully agrees to hold one, and this is the point where From Beyond the Grave first shows off its strengths, and first-time director Kevin Connor reveals his deft hand for horror. For no sooner than the séance starts than Charlton is suddenly thrust into a ghostly space, a minimalist hellscape sketched out of a few bare tree branches and empty teal space. It's so preposterously unreal that it manages to feel less like low-budget filmmaking (which is, of course, exactly what it is), and more like some kind of half-formed pocket universe that symbolises a space as much as it depicts one. We're thrown into it suddenly enough for the contrast to be shocking all by itself: Connor was an editor before he was a director, and he has an editor's sense of how the collision of two shots can force a response out of the viewer. The suddenness of the cutting keeps up when Charlton is confronted with a hideous figure (Marcel Steiner), clammy and grey with corpse-like sunken eyes, who advances silently before stabbing Charlton, who jolts back to the séance with a scream.

Over the days to come, the figure appears in the old mirror, demanding to be fed in a guttural voice; Charlton, seemingly without even having the capacity to disobey, obliges by bringing home prostitutes and murdering them. With every death, the being in the mirror seems a little more robust and lively, and Charlton seems a bit more haggard. And of course, the time will come when the ghost is ready to be reborn into the world. None of this is all that surprising; it's all in the execution, which has a headlong flow and feeling of days slipping by in a constant blur of murder and snarling threats by the effectively creepy ghost (again, Connor was an editor by trade, and that's especially clear in this segment). The horror of the sequence is about being inexorably controlled by a being of unadorned malevolence, but it's also about the much smaller misery of just being tired from being forced to do something constantly, and Warner's beleaguered performance does fantastic work in getting us to that point.

It's a rock-solid opening, and it's neatly matched by the second segment, which makes up for in complexity and psychological acuity what it lacks in overripe horror atmosphere. Christopher Lowe (Ian Bannen) is a miserable nobody, with a wife, Mabel (Diana Dors), that he can't stand - the feeling is mutual - and a son (John O'Farrell) who barely seems to register his existence. One day, on the way home from work, he spontaneously buys shoelaces from a shabby street peddler (Donald Pleasance) with a misspelled, handmade sign declaring himself to be an out-of-luck military veteran. Lowe, who had an undistinguished stint in the military himself, leaps at the opportunity to finally impress somebody: he manages to steal a medal from Temptations, Limited, one suggesting he was higher-ranking and considerably more valorous than was the case. Soon, he and the peddler - named Jim Underwood - have struck up a friendship, and he's also taken by Jim's daughter Emily (Angela Pleasance, Donald's daughter). She reciprocates, and has a potential scheme for how to remove Mabel from the picture. It involves witchcraft, and it also involves Lowe being the unwitting dupe of a greater plot than he realises.

"An Act of Kindness" - this segment's title - is rather more complicated than the above lets on, mostly because of how elliptically it sketches out Lowe's pathetic misery and his seedy attempts to break out of it. Bannen is superb at playing a gregarious surface-level affability, the sort of man who is hellbent on exuding a sense of emotionally neutral satisfaction, stripping his humanity in one way that makes it easy to start sacrificing it in others, once the possibility of doing away with his wife comes up. It's the most sedate and domestic of the segments in From Beyond the Grave, with Connor favoring slightly wide shots that make it feel a bit like a television theater adaptation; this refusal to do anything to foreground genre means that it sneaks up on us, and that sense of a character drama being infested with horror material, to the great misfortune of its protagonist, goes a long way towards making this an unusually compelling and full story, certainly the most elaborate of this film's four segments.

The third story is our comic interlude, in which Reginald Warren (Ian Carmichael) swaps the price tags on two snuff boxes to give himself a little bit of a deal. On the train ride home, he sits across from a very goofy-looking and goofy-sounding woman, a certain Madame Orloff (Margaret Leighton), who declares that he has an "elemental" on his shoulder - an invisible demon that only children, animals, and psychics like herself can detect. And it's a murderous one, the worst kind. Warren is content to forget all about it, but things start piling up pretty fast: his dog runs away, and his wife Susan (Nyree Dawn Porter) starts experience physical attacks with no apparent attacker. And soon, the Warrens feel ready to call upon Madame Orloff to have her stage an exorcism.

This segment lives and dies on Leighton's performance: without the right kind of comic energy, it's easy to imagine this coming across as stupid or shrill. She hits her target perfectly, I think, concocting a prim, batty figure of great authority and dignity even as she's flopping about and squawking in a ridiculously keyed-up tone of voice. What's particularly impressive is that she does this while the sequence also persistently makes sure we feel that the elemental is a genuine, present threat, maintaining the stakes of the story and even providing us with a rather shocking climax of horror movie vindictiveness. Carmichael and Porter get blown off the screen by Leighton a little bit, which is the main reason it's hard to regard this at quite the level of the first two segments; it's more fun as a collection of different tones than as a story. Still, we're miles away from a genuinely failed story, and this showcases the great privilege of anthology films: as long as it can hustle us to its sucker-punch ending, there doesn't need to be much in the way of sophisticated storytelling.

The last client of the day is William Seaton (Ian Ogilvy), who falls in love with a hideous ornate door propped against one wall, and while he doesn't have enough cash to pay for it, the proprietor agrees to knock a little bit off the price tag. With this done, he steps away, conspicuously leaving, the register drawer open, so that Seaton - who had just complained about how this was going to leave him flat broke - has a good long opportunity to steal some money back. We do not see this happen; the moment it would have taken place is hidden in a cut. And this raises the question of whether Seaton deserves the karmic retribution he would seem to get, when he and his wife Rosemary (Lesley-Anne Down) install the door over their stationery closet. To their amazement, when the door is opened, it leads them into an old-fashioned room, painted all in blue; this proves to be the study of a warlock named Sir Michael Sinclair (Jack Watson), who many decades ago cursed the door to trap innocents, so that he might devour their souls and return to the world of the living.

This final segment is the odd duck of the film, for a couple of reasons. It's quite short and simple, for one thing: there's not really a sense of Sinclair's menace building or expanding, just a bunch of punchy little scenes in the blue room. It also interacts with the framing narrative differently from the other three, though how this happens won't be clear until it ends. This all leads to a slight feeling that it lacks substance; Ogilvy and Down play off of each other extremely well, giving their married couple a spiky, playful vibe that pays off very nicely when they have to take turns rescuing each other, but there's no depth to them like we get with Lowe, nor the sense of being worn down that we get with Charlton and Warren. It is, of the four stories, the one that feels the most like a light yarn; there are no stakes and no depths, just a desire to spook us with a bizarre angry ghost living inside a pocket universe behind a door. It's something of a companion piece to the first story, in this respect, without the horrible sense of fatalism and evil; it's almost a plucky finale to the whole movie, in fact, save for a quick little button in which we start to learn how much more there is to the proprietor than he lets on. But this all turns out to be motivated, and the motivation adds a nice wrinkle to what would otherwise be a formulaic collection of tales.

Even with the formula in place, though, From Beyond the Grave is a great delight, showing off all of Amicus's strengths and demonstrating fewer weakness than literally any of their other films. If it's something of the last hurrah for the studio in its most ideal state, it's a joyful one; unlike Hammer, which spent the '70s wheezing its way into a pauper's grave, the last of Amicus's signature anthology films would never give you the slightest thought that the end was near, or that they couldn't continue on with this fun little low-budget spookshows indefinitely. Alas that it was not the case!

The unifying theme of the film this time around is the work of Ronald Chetwynd-Hayes, a beloved author of ghost stories, and while I have no exposure to his work outside of this movie, if this is in any way representative, I can definitely see the appeal. Unlike pretty much all of the other Amicus portmanteau films up to this point, the stories in From Beyond the Grave don't build up to ironic endings in which the protagonists' flaws karmically manifest in their comeuppance; they're just quick little yarns about spooky shit happening sort of at random.

Karma is still involved, and it comes in the form of the framing narrative, which is awfully clever and thoughtful, though it's much more insubstantial than I might have liked, given that this the only place where we get any Cushing this time around. He's playing the proprietor of Temptations, Limited, an overstuffed curiosity and antique shop on a quiet side street, and we know right from the start that something mysterious is up with it, because this side street somehow magically appears during a very well-hidden cut during a series of tracking shots through an old rural churchyard. Also because it is named "Temptations, Limited". Over the course of the movie, four different men show up at the store, and find themselves drawn to a particular object; they acquire the object through somewhat shady means, and that's when the curse activates. As payment for trying to cheat the amiable old man (or trickster demon, as the case might be), something horrible happens to them.

The first customer is Edward Charlton (David Warner), an antiques expert who wants a lavish old mirror that comes with a too-steep £250 price tag. Swiftly and decisively he lies to the proprietor that it's obviously a replica, and gets the cost slashed down to £25, and takes it home, where he proudly displays it over the dining table. At a party, one of his friends suggests that it looks like the perfect mirror for a séance, and so everybody playfully agrees to hold one, and this is the point where From Beyond the Grave first shows off its strengths, and first-time director Kevin Connor reveals his deft hand for horror. For no sooner than the séance starts than Charlton is suddenly thrust into a ghostly space, a minimalist hellscape sketched out of a few bare tree branches and empty teal space. It's so preposterously unreal that it manages to feel less like low-budget filmmaking (which is, of course, exactly what it is), and more like some kind of half-formed pocket universe that symbolises a space as much as it depicts one. We're thrown into it suddenly enough for the contrast to be shocking all by itself: Connor was an editor before he was a director, and he has an editor's sense of how the collision of two shots can force a response out of the viewer. The suddenness of the cutting keeps up when Charlton is confronted with a hideous figure (Marcel Steiner), clammy and grey with corpse-like sunken eyes, who advances silently before stabbing Charlton, who jolts back to the séance with a scream.

Over the days to come, the figure appears in the old mirror, demanding to be fed in a guttural voice; Charlton, seemingly without even having the capacity to disobey, obliges by bringing home prostitutes and murdering them. With every death, the being in the mirror seems a little more robust and lively, and Charlton seems a bit more haggard. And of course, the time will come when the ghost is ready to be reborn into the world. None of this is all that surprising; it's all in the execution, which has a headlong flow and feeling of days slipping by in a constant blur of murder and snarling threats by the effectively creepy ghost (again, Connor was an editor by trade, and that's especially clear in this segment). The horror of the sequence is about being inexorably controlled by a being of unadorned malevolence, but it's also about the much smaller misery of just being tired from being forced to do something constantly, and Warner's beleaguered performance does fantastic work in getting us to that point.

It's a rock-solid opening, and it's neatly matched by the second segment, which makes up for in complexity and psychological acuity what it lacks in overripe horror atmosphere. Christopher Lowe (Ian Bannen) is a miserable nobody, with a wife, Mabel (Diana Dors), that he can't stand - the feeling is mutual - and a son (John O'Farrell) who barely seems to register his existence. One day, on the way home from work, he spontaneously buys shoelaces from a shabby street peddler (Donald Pleasance) with a misspelled, handmade sign declaring himself to be an out-of-luck military veteran. Lowe, who had an undistinguished stint in the military himself, leaps at the opportunity to finally impress somebody: he manages to steal a medal from Temptations, Limited, one suggesting he was higher-ranking and considerably more valorous than was the case. Soon, he and the peddler - named Jim Underwood - have struck up a friendship, and he's also taken by Jim's daughter Emily (Angela Pleasance, Donald's daughter). She reciprocates, and has a potential scheme for how to remove Mabel from the picture. It involves witchcraft, and it also involves Lowe being the unwitting dupe of a greater plot than he realises.

"An Act of Kindness" - this segment's title - is rather more complicated than the above lets on, mostly because of how elliptically it sketches out Lowe's pathetic misery and his seedy attempts to break out of it. Bannen is superb at playing a gregarious surface-level affability, the sort of man who is hellbent on exuding a sense of emotionally neutral satisfaction, stripping his humanity in one way that makes it easy to start sacrificing it in others, once the possibility of doing away with his wife comes up. It's the most sedate and domestic of the segments in From Beyond the Grave, with Connor favoring slightly wide shots that make it feel a bit like a television theater adaptation; this refusal to do anything to foreground genre means that it sneaks up on us, and that sense of a character drama being infested with horror material, to the great misfortune of its protagonist, goes a long way towards making this an unusually compelling and full story, certainly the most elaborate of this film's four segments.

The third story is our comic interlude, in which Reginald Warren (Ian Carmichael) swaps the price tags on two snuff boxes to give himself a little bit of a deal. On the train ride home, he sits across from a very goofy-looking and goofy-sounding woman, a certain Madame Orloff (Margaret Leighton), who declares that he has an "elemental" on his shoulder - an invisible demon that only children, animals, and psychics like herself can detect. And it's a murderous one, the worst kind. Warren is content to forget all about it, but things start piling up pretty fast: his dog runs away, and his wife Susan (Nyree Dawn Porter) starts experience physical attacks with no apparent attacker. And soon, the Warrens feel ready to call upon Madame Orloff to have her stage an exorcism.

This segment lives and dies on Leighton's performance: without the right kind of comic energy, it's easy to imagine this coming across as stupid or shrill. She hits her target perfectly, I think, concocting a prim, batty figure of great authority and dignity even as she's flopping about and squawking in a ridiculously keyed-up tone of voice. What's particularly impressive is that she does this while the sequence also persistently makes sure we feel that the elemental is a genuine, present threat, maintaining the stakes of the story and even providing us with a rather shocking climax of horror movie vindictiveness. Carmichael and Porter get blown off the screen by Leighton a little bit, which is the main reason it's hard to regard this at quite the level of the first two segments; it's more fun as a collection of different tones than as a story. Still, we're miles away from a genuinely failed story, and this showcases the great privilege of anthology films: as long as it can hustle us to its sucker-punch ending, there doesn't need to be much in the way of sophisticated storytelling.

The last client of the day is William Seaton (Ian Ogilvy), who falls in love with a hideous ornate door propped against one wall, and while he doesn't have enough cash to pay for it, the proprietor agrees to knock a little bit off the price tag. With this done, he steps away, conspicuously leaving, the register drawer open, so that Seaton - who had just complained about how this was going to leave him flat broke - has a good long opportunity to steal some money back. We do not see this happen; the moment it would have taken place is hidden in a cut. And this raises the question of whether Seaton deserves the karmic retribution he would seem to get, when he and his wife Rosemary (Lesley-Anne Down) install the door over their stationery closet. To their amazement, when the door is opened, it leads them into an old-fashioned room, painted all in blue; this proves to be the study of a warlock named Sir Michael Sinclair (Jack Watson), who many decades ago cursed the door to trap innocents, so that he might devour their souls and return to the world of the living.

This final segment is the odd duck of the film, for a couple of reasons. It's quite short and simple, for one thing: there's not really a sense of Sinclair's menace building or expanding, just a bunch of punchy little scenes in the blue room. It also interacts with the framing narrative differently from the other three, though how this happens won't be clear until it ends. This all leads to a slight feeling that it lacks substance; Ogilvy and Down play off of each other extremely well, giving their married couple a spiky, playful vibe that pays off very nicely when they have to take turns rescuing each other, but there's no depth to them like we get with Lowe, nor the sense of being worn down that we get with Charlton and Warren. It is, of the four stories, the one that feels the most like a light yarn; there are no stakes and no depths, just a desire to spook us with a bizarre angry ghost living inside a pocket universe behind a door. It's something of a companion piece to the first story, in this respect, without the horrible sense of fatalism and evil; it's almost a plucky finale to the whole movie, in fact, save for a quick little button in which we start to learn how much more there is to the proprietor than he lets on. But this all turns out to be motivated, and the motivation adds a nice wrinkle to what would otherwise be a formulaic collection of tales.

Even with the formula in place, though, From Beyond the Grave is a great delight, showing off all of Amicus's strengths and demonstrating fewer weakness than literally any of their other films. If it's something of the last hurrah for the studio in its most ideal state, it's a joyful one; unlike Hammer, which spent the '70s wheezing its way into a pauper's grave, the last of Amicus's signature anthology films would never give you the slightest thought that the end was near, or that they couldn't continue on with this fun little low-budget spookshows indefinitely. Alas that it was not the case!

Categories: amicus productions, anthology films, british cinema, horror, scary ghosties