The war at home

According to a certain strand of criticism that has existed since the early 1960s, the biggest single shortcoming with Ingmar Bergman is that he is fundamentally apolitical. His international heyday exactly overlapped with a moment of heightened political activism around the world from artists of every medium, much of it oriented in opposition to the United States' military intervention in Vietnam, and the omnipresent threat of the Cold War catching fire. During this incredibly fraught time, Bergman was steadily flinging himself at philosophical esoterica that had everything to do with great cosmic questions about God and personal identity and the pain of interpersonal relationships; his films were, according this line of thought, conspicuously detached from real-world concerns and irredeemably bourgeois and middlebrow.

I have my own thoughts about whether this is a productive line of criticism, on at least two grounds: first, politically activist art is almost invariably terrible, and when it's not, it's generally because the art has been allowed to completely smother the political activism; second, the first time Bergman made an openly political film, it was the appalling This Can't Happen Here, and if Bergman's films remaining disconnected from the world around them was the price that had to be paid for him to never again make anything that idiotic and incompetent, it was a bargain. Nonetheless, there did come a point where the director made an effort to acknowledge, for at least the span of one feature film (and at 103 minutes, quite a long feature film by his standards), the astonishing and terrifyingly chaotic state of the world in the late 1960s, which was hitting its peak of chaos in 1968, the year that Shame was released. For Shame is that politically-minded-by-Bergman-standards film, of course, which is why I'm going on about all of this right now.

The film is not literally about Vietnam, and when pressed, Bergman insisted that it wasn't metaphorically about Vietnam, either. But a movie about the devastating human cost of war released in 1968 was going to have certain unmistakable resonances whether the filmmakers intended it to or not. Even more than that, it's kind of irresistibly about being an artist who insists on remaining detached from the ongoing concerns of the world, only to find that the world is going to come for you no matter how stubbornly apolitical you want to be. Specifically, it's about the Rosenbergs, Jan (Max von Sydow) and Eva (Liv Ullmann), former violinists who have moved to an island somewhere far away from the urban centers of Sweden, hoping to avoid the civil war that has apparently broken out on the mainland, in whatever broken-down near-future this is meant to be. They've been there for a few years, and Jan is utterly at peace with what their small, constrained lives, though Eva is considerably less certain if they can justify living this way. Soon it sort of won't matter; one afternoon, after returning from a ferry trip to sell berries in the nearest town, the Rosenbergs' yard is infested with paratroopers, and discover that the war has come to them. Over the rest of the movie, they will be captured and released multiple times, interrogated for possible sedition, and find their marriage tested explicitly by the presence of mayor-turned-military leader Jacobi (Gunnar Björnstrand), who offers the couple allowances in exchange for romantic attention from Eva. But mostly, it is tested due to their own secret selves, with Eva growing increasingly repulsed by Jan's wormy attempts to avoid having an opinion or taking a stand on anything.

We have, in other words, Bergman's second consecutive story in which the marriage between characters played by Ullmann and von Sydow find their relationship disintegrating due to the man's failures, set on an isolated island, and told through the veil of a genre. And indeed, Hour of the Wolf, Shame, and the following year's The Passion of Anna (which continues the formula) are often spoken of together as a loose trilogy (the Island Trilogy is how I've usually heard it referenced). I will confess right now that I think Hour of the Wolf is the stronger of the two 1968 films, which is not the consensus; all three films tend to be overshadowed by the earlier loose trilogy of the 1960s, Through a Glass Darkly and Winter Light and The Silence, and all six films are hidden by the blinding glare from the epochal Persona, but Shame is surely the best-known and most highly-acclaimed of the three island films. This was not a conclusion shared by Bergman himself, and I largely agree with his criticisms of this particular film: he felt that the opening half of the movie (basically everything up to the point that Eva starts openly disdaining Jan; it's conveniently marked out by a fade-to-black that comes almost exactly one hour into the film) was too messy and unfocused, that he was indulging in saying the same thing over and over again & could easily have condensed it all into a prologue, and that the heart of the film was the marital conflict that really just isn't present at all before the midway point.

I might phrase it a bit differently: there are two distinct movies within Shame, and they never speak to each other. I have mentioned that this is a genre film: of course, it's specifically a war film, and much of that opening hour that Bergman later regretted is all taken up with the stuff of war cinema, though more of the grinding, miserable terror of being a civilian living under constant threat of violence erupting in your neighborhood, than of combat and military action itself. That is to say, an American might have a hard time recognising the genre elements here, but I suspect that any European in the 1960s, having been exposed to Italian Neorealism at the right time, would absolutely spot the ways in which this belongs to a breed of "how the citizenry copes with war" films that are, I think, somewhat unique to that continent. But this is all beside the point. Shame is a war film, much more actively than Hour of the Wolf was a horror film. And I think that's exactly where the problem lies. Hour of the Wolf knew what it was about: it is the wife's experience of watching her husband fall into madness and hallucination, and discover the deep fear and pain of being trapped in a marriage with someone who is possibly dangerous and certainly too unstable to withstand the emotional needs of an intimate relationship. Horror is used in that film as a way into the domestic drama, but it is always a domestic drama first. Shame doesn't manage the same trick: the war material is, after a fashion, used as a metaphor for the marital drama, but it also uses it as a commentary on the arbitrary violence and social decay of war. And on the flipside, the marital drama doesn't really need war, the way that Hour of the Wolf "needs" horror" - there needs to be something of consequence for the couple to disagree about, but it needn't be political at all. In fact, the film even provides a better alternative, in the form of the couple's hypothetical child, and how they would spar over raising it.

And these are the two films I mentioned: it is a war film and a domestic drama, not a war film that is a domestic drama. That results in something that feels much less precise than Hour of the Wolf, or really any of Bergman's films from the 1960s, notwithstanding the bizarre farce of 1964's All These Women (which nobody in their right mind would call a major work). If I am to recklessly launch wholeheartedly into baseless speculation, it feels like Bergman's heart belonged exactly where we would assume, based on everything he'd made prior to this point: the story of a marriage being tested and found shaky, with lots of opportunities for acting fireworks. Which are, to be certain, gorgeous fireworks, and we'll get there just as soon as I'm done complaining about the story. It doesn't seem like he really cares about making a war film, though I think he liked the idea of having made a film about the dehumanising effects of life in a military occupation. But that film and the story of the Rosenbergs don't inherently comment on each other, and I don't think they have been made to do so, either.

Because of this, Shame feels awfully shapeless to me, a collection of scenes that are sometimes great and sometimes merely good, but often disconnected from each other. It's busy as hell, a far cry from all of Bergman's best masterpieces, which generally feel like almost nothing happens during their running times. Perhaps the moral here is that Bergman had a very distinct skill set, and he thrived only when doing exactly the things he could do better than any other filmmaker of his generation. Perhaps the moral is that I have an unnecessarily particular mental model for what makes "an Ingmar Bergman film", and I'm not willing to expand it just for a war movie that is, even in its best incarnation, not doing anything indisputably new with the form.

Whatever Shame lacks as a narrative and an exploration of themes, though, it at least makes up for in its exemplary craftsmanship, and magnificent performances, as I promised I'd talk about. Ullmann and von Sydow are both absolutely superb here; Ullmann's third world-class performance in her third film with Bergman, though I'd argue that she has been offered fewer showpiece moments than in either Persona or Hour of the Wolf. That means that von Sydow is arguably the bigger stand-out, in what I think I am comfortable anointing the best performance he ever gave for this director. I think it's fair to say that, in the decades since Bergman's career exploded into the international art film Zeitgeist, von Sydow has emerged as probably the single most famous and beloved of all his acting collaborators, second maybe only to Ullmann herself; but I will admit that he's not one of my favorites. Setting aside the self-evident reality that all of the best performances in Bergman's movies come from women, I'm generally much more excited by Björnstrand or Erland Josephson's work for the director; this surely has as much to do with the roles von Sydow got as anything (Through a Glass Darkly, in particular, seems tailor-made to make sure he doesn't stand out in the ensemble). Still, what he's up to in this film is absolutely the equal to anything else done by a male in any Bergman film, in tightly-wound, neurotic characterisation of Jan as a man who has rationalised terror as pragmatism and is, as the film progresses, torn open in a most uncomfortable, savage way by being forced into self-reflection that he's been putting off for so long. Eva's arc is fairly straightforward, and Ullmann handles it well: comfort to guilt-stricken comfort to anger at the collapse of the world around her. It's tidy, though. Jan's arc is much more savage, with von Sydow looking, as the film progresses, like he's on the verge of disintegrating right before our eyes: he is dazed, raw in voice and face, a haggard husk tottering around unsteadily.

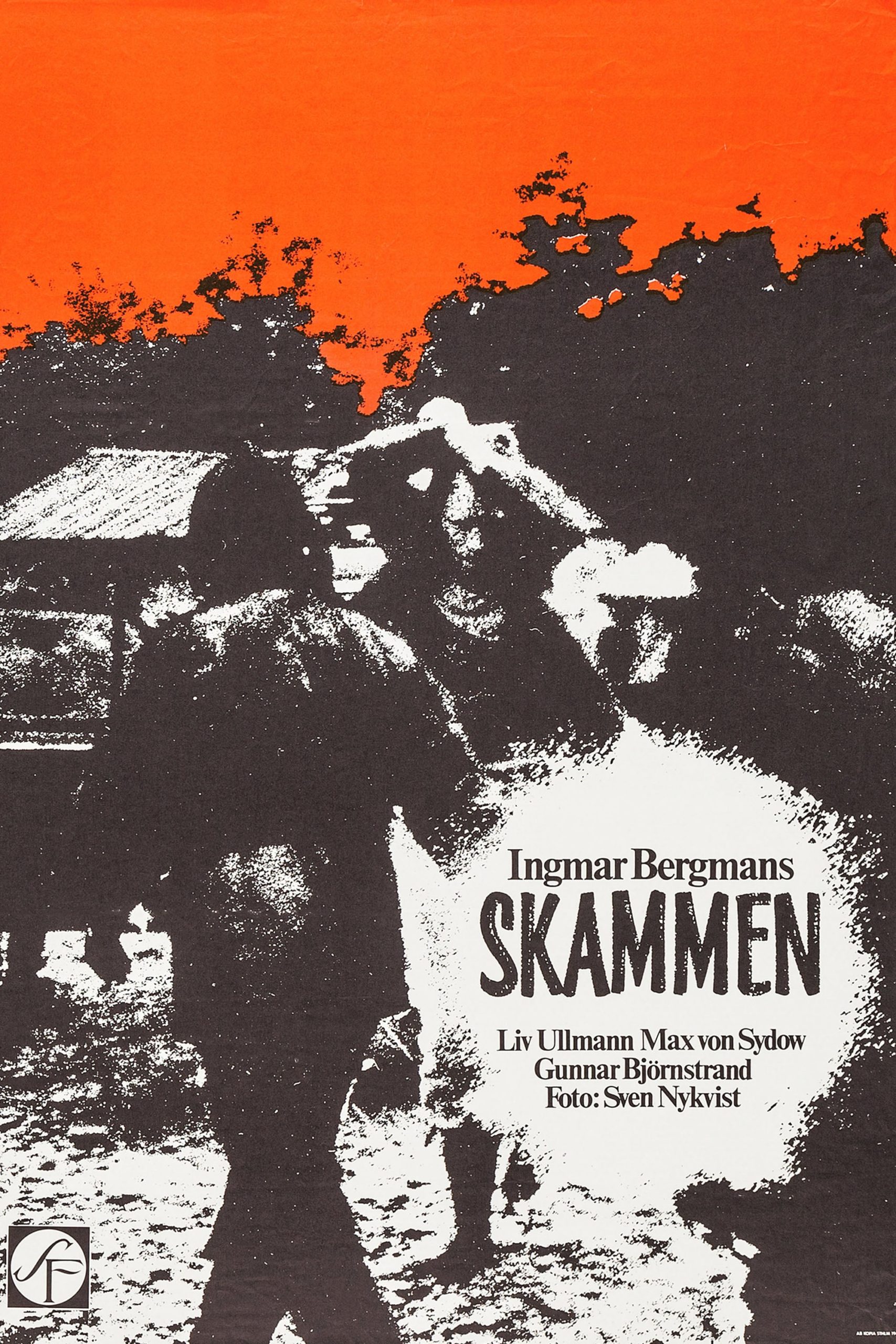

On top of the expected great acting, there's the expected great cinematography by Sven Nykvist, who is drawing very directly from realism: the film is focused on a full range of greys with less showy contrast than he often used, and the compositions tend to be boxier and less prone to poetic movements and striking angles. This fits the content so well that it's hard to grouse that it's a bit less knock-you-on-your-ass pretty than most of his work in black-and-white with Bergman. But it does mean, I think, that this is a rare example of the editing and sound taking precedence over the visuals, the sound especially: the opening of the film, under its credits (which are styled differently than the usual Bergman credits: still whit text on black, but it's a different typeface - it has serifs! - and the cards are stuffed more full. It gives the thing the vague sense of an official report), is an increasingly chaotic and jarring montage of war noises, all of them sounding overly-sweetened and fake, but in a way that only adds to the feeling of disruptive violence. And throughout the rest of the film, offscreen sounds of war will be a significant way the film both adds to its realism and also its sense of despair at the seeming end of civilisation.

So definitely not a film without some very fine merits, and the cluster of meanings we can assign to that word, Shame, put it in line with all of Bergman's great work of the 1960s. It is not so much that the title is a crux, as that is is deliberately all-encompassing: it can refer to Bergman's shame at dodging politics or Jan's shame at the same, God's shame at creating a violent world; humanity's shame at embracing war as a first resort; the same of being a bad and weak husband; and that's without even pausing to think about it. All of these get us to the Big Questions of '60s art cinema, and Bergman's particular contributions to the form; while I don't think that making a war film came naturally to him, he figured out a way to make it his own. The result is far from my favorite work by the director, but it's still a formidable work that demands being grappled with, both for its position within his career, and within the greater corpus of cinema from that era, and its uncertain status in Bergman's canon compared to his biggest-name titles (I think it is broadly considered one of his "essential" films, but the least-essential of those) should absolutely not be meant as a sign that this is anything but a major work, even if I'm not sure that it's successful.

I have my own thoughts about whether this is a productive line of criticism, on at least two grounds: first, politically activist art is almost invariably terrible, and when it's not, it's generally because the art has been allowed to completely smother the political activism; second, the first time Bergman made an openly political film, it was the appalling This Can't Happen Here, and if Bergman's films remaining disconnected from the world around them was the price that had to be paid for him to never again make anything that idiotic and incompetent, it was a bargain. Nonetheless, there did come a point where the director made an effort to acknowledge, for at least the span of one feature film (and at 103 minutes, quite a long feature film by his standards), the astonishing and terrifyingly chaotic state of the world in the late 1960s, which was hitting its peak of chaos in 1968, the year that Shame was released. For Shame is that politically-minded-by-Bergman-standards film, of course, which is why I'm going on about all of this right now.

The film is not literally about Vietnam, and when pressed, Bergman insisted that it wasn't metaphorically about Vietnam, either. But a movie about the devastating human cost of war released in 1968 was going to have certain unmistakable resonances whether the filmmakers intended it to or not. Even more than that, it's kind of irresistibly about being an artist who insists on remaining detached from the ongoing concerns of the world, only to find that the world is going to come for you no matter how stubbornly apolitical you want to be. Specifically, it's about the Rosenbergs, Jan (Max von Sydow) and Eva (Liv Ullmann), former violinists who have moved to an island somewhere far away from the urban centers of Sweden, hoping to avoid the civil war that has apparently broken out on the mainland, in whatever broken-down near-future this is meant to be. They've been there for a few years, and Jan is utterly at peace with what their small, constrained lives, though Eva is considerably less certain if they can justify living this way. Soon it sort of won't matter; one afternoon, after returning from a ferry trip to sell berries in the nearest town, the Rosenbergs' yard is infested with paratroopers, and discover that the war has come to them. Over the rest of the movie, they will be captured and released multiple times, interrogated for possible sedition, and find their marriage tested explicitly by the presence of mayor-turned-military leader Jacobi (Gunnar Björnstrand), who offers the couple allowances in exchange for romantic attention from Eva. But mostly, it is tested due to their own secret selves, with Eva growing increasingly repulsed by Jan's wormy attempts to avoid having an opinion or taking a stand on anything.

We have, in other words, Bergman's second consecutive story in which the marriage between characters played by Ullmann and von Sydow find their relationship disintegrating due to the man's failures, set on an isolated island, and told through the veil of a genre. And indeed, Hour of the Wolf, Shame, and the following year's The Passion of Anna (which continues the formula) are often spoken of together as a loose trilogy (the Island Trilogy is how I've usually heard it referenced). I will confess right now that I think Hour of the Wolf is the stronger of the two 1968 films, which is not the consensus; all three films tend to be overshadowed by the earlier loose trilogy of the 1960s, Through a Glass Darkly and Winter Light and The Silence, and all six films are hidden by the blinding glare from the epochal Persona, but Shame is surely the best-known and most highly-acclaimed of the three island films. This was not a conclusion shared by Bergman himself, and I largely agree with his criticisms of this particular film: he felt that the opening half of the movie (basically everything up to the point that Eva starts openly disdaining Jan; it's conveniently marked out by a fade-to-black that comes almost exactly one hour into the film) was too messy and unfocused, that he was indulging in saying the same thing over and over again & could easily have condensed it all into a prologue, and that the heart of the film was the marital conflict that really just isn't present at all before the midway point.

I might phrase it a bit differently: there are two distinct movies within Shame, and they never speak to each other. I have mentioned that this is a genre film: of course, it's specifically a war film, and much of that opening hour that Bergman later regretted is all taken up with the stuff of war cinema, though more of the grinding, miserable terror of being a civilian living under constant threat of violence erupting in your neighborhood, than of combat and military action itself. That is to say, an American might have a hard time recognising the genre elements here, but I suspect that any European in the 1960s, having been exposed to Italian Neorealism at the right time, would absolutely spot the ways in which this belongs to a breed of "how the citizenry copes with war" films that are, I think, somewhat unique to that continent. But this is all beside the point. Shame is a war film, much more actively than Hour of the Wolf was a horror film. And I think that's exactly where the problem lies. Hour of the Wolf knew what it was about: it is the wife's experience of watching her husband fall into madness and hallucination, and discover the deep fear and pain of being trapped in a marriage with someone who is possibly dangerous and certainly too unstable to withstand the emotional needs of an intimate relationship. Horror is used in that film as a way into the domestic drama, but it is always a domestic drama first. Shame doesn't manage the same trick: the war material is, after a fashion, used as a metaphor for the marital drama, but it also uses it as a commentary on the arbitrary violence and social decay of war. And on the flipside, the marital drama doesn't really need war, the way that Hour of the Wolf "needs" horror" - there needs to be something of consequence for the couple to disagree about, but it needn't be political at all. In fact, the film even provides a better alternative, in the form of the couple's hypothetical child, and how they would spar over raising it.

And these are the two films I mentioned: it is a war film and a domestic drama, not a war film that is a domestic drama. That results in something that feels much less precise than Hour of the Wolf, or really any of Bergman's films from the 1960s, notwithstanding the bizarre farce of 1964's All These Women (which nobody in their right mind would call a major work). If I am to recklessly launch wholeheartedly into baseless speculation, it feels like Bergman's heart belonged exactly where we would assume, based on everything he'd made prior to this point: the story of a marriage being tested and found shaky, with lots of opportunities for acting fireworks. Which are, to be certain, gorgeous fireworks, and we'll get there just as soon as I'm done complaining about the story. It doesn't seem like he really cares about making a war film, though I think he liked the idea of having made a film about the dehumanising effects of life in a military occupation. But that film and the story of the Rosenbergs don't inherently comment on each other, and I don't think they have been made to do so, either.

Because of this, Shame feels awfully shapeless to me, a collection of scenes that are sometimes great and sometimes merely good, but often disconnected from each other. It's busy as hell, a far cry from all of Bergman's best masterpieces, which generally feel like almost nothing happens during their running times. Perhaps the moral here is that Bergman had a very distinct skill set, and he thrived only when doing exactly the things he could do better than any other filmmaker of his generation. Perhaps the moral is that I have an unnecessarily particular mental model for what makes "an Ingmar Bergman film", and I'm not willing to expand it just for a war movie that is, even in its best incarnation, not doing anything indisputably new with the form.

Whatever Shame lacks as a narrative and an exploration of themes, though, it at least makes up for in its exemplary craftsmanship, and magnificent performances, as I promised I'd talk about. Ullmann and von Sydow are both absolutely superb here; Ullmann's third world-class performance in her third film with Bergman, though I'd argue that she has been offered fewer showpiece moments than in either Persona or Hour of the Wolf. That means that von Sydow is arguably the bigger stand-out, in what I think I am comfortable anointing the best performance he ever gave for this director. I think it's fair to say that, in the decades since Bergman's career exploded into the international art film Zeitgeist, von Sydow has emerged as probably the single most famous and beloved of all his acting collaborators, second maybe only to Ullmann herself; but I will admit that he's not one of my favorites. Setting aside the self-evident reality that all of the best performances in Bergman's movies come from women, I'm generally much more excited by Björnstrand or Erland Josephson's work for the director; this surely has as much to do with the roles von Sydow got as anything (Through a Glass Darkly, in particular, seems tailor-made to make sure he doesn't stand out in the ensemble). Still, what he's up to in this film is absolutely the equal to anything else done by a male in any Bergman film, in tightly-wound, neurotic characterisation of Jan as a man who has rationalised terror as pragmatism and is, as the film progresses, torn open in a most uncomfortable, savage way by being forced into self-reflection that he's been putting off for so long. Eva's arc is fairly straightforward, and Ullmann handles it well: comfort to guilt-stricken comfort to anger at the collapse of the world around her. It's tidy, though. Jan's arc is much more savage, with von Sydow looking, as the film progresses, like he's on the verge of disintegrating right before our eyes: he is dazed, raw in voice and face, a haggard husk tottering around unsteadily.

On top of the expected great acting, there's the expected great cinematography by Sven Nykvist, who is drawing very directly from realism: the film is focused on a full range of greys with less showy contrast than he often used, and the compositions tend to be boxier and less prone to poetic movements and striking angles. This fits the content so well that it's hard to grouse that it's a bit less knock-you-on-your-ass pretty than most of his work in black-and-white with Bergman. But it does mean, I think, that this is a rare example of the editing and sound taking precedence over the visuals, the sound especially: the opening of the film, under its credits (which are styled differently than the usual Bergman credits: still whit text on black, but it's a different typeface - it has serifs! - and the cards are stuffed more full. It gives the thing the vague sense of an official report), is an increasingly chaotic and jarring montage of war noises, all of them sounding overly-sweetened and fake, but in a way that only adds to the feeling of disruptive violence. And throughout the rest of the film, offscreen sounds of war will be a significant way the film both adds to its realism and also its sense of despair at the seeming end of civilisation.

So definitely not a film without some very fine merits, and the cluster of meanings we can assign to that word, Shame, put it in line with all of Bergman's great work of the 1960s. It is not so much that the title is a crux, as that is is deliberately all-encompassing: it can refer to Bergman's shame at dodging politics or Jan's shame at the same, God's shame at creating a violent world; humanity's shame at embracing war as a first resort; the same of being a bad and weak husband; and that's without even pausing to think about it. All of these get us to the Big Questions of '60s art cinema, and Bergman's particular contributions to the form; while I don't think that making a war film came naturally to him, he figured out a way to make it his own. The result is far from my favorite work by the director, but it's still a formidable work that demands being grappled with, both for its position within his career, and within the greater corpus of cinema from that era, and its uncertain status in Bergman's canon compared to his biggest-name titles (I think it is broadly considered one of his "essential" films, but the least-essential of those) should absolutely not be meant as a sign that this is anything but a major work, even if I'm not sure that it's successful.