Life with Father

In the year of our Lord 2020, you have either made your peace with Sofia Coppola's entire filmmaking project focusing on stories of upper-class women suffering from an indescribable ennui - women whose biographies overlap in significant ways with Coppola herself - or you have not. As long as they remain insightful and clever, I'm an unapologetic fanboy. So I'm not going to go over that whole song-and-dance with On the Rocks, her seventh feature, and one that lives securely inside her comfort zone. It's basically an aged-up version of Somewhere from 2010, a very quite and low-key sketch of boredom and a gulf of emotional inaccessibility between a father and daughter, and the film that probably best exemplifies the "so, you really cannot imagine what it's like not to be rich?" criticism of the director's filmography. It's also a film that has very patiently set up permanent residence in my brain in the intervening decade, constantly cropping up when I don't expect it to, in order to remind me of how nuanced and precise and deeply felt it is as a nonjudgmental character study, earning my besotted adoration in part by never doing anything to demand it other than by being simple and honest. And because of this, I am inclined to give On the Rocks quite a bit of benefit of the doubt, and maybe in a perfect world, I would wait ten years to actually write this review. Unfortunately, reviews of new movies don't work that way.

On the Rocks is a little bit about how tiring it is to be the daughter of a celebrated father (thus Somewhere) and a little bit about how tiring it is to have an emotionally distant husband who is very nice in a detached way as he leaves you alone in a glamorous, glossy apartment (thus Lost in Translation, which I imagine remains Coppola's most highly-regarded film), and a little bit about shiny surfaces that don't have much to them beneath the shine (Coppola is working with cinematographer Philippe Le Sourd again after their magnificent collaboration on the 2017 version of The Beguiled, and he makes New York at night sparkle like a black diamond), and really a little bit about a lot of things. All these things center upon Laura (Rashida Jones, herself a daughter of a world-renowned father in his own medium), who we meet on the day of her wedding to Dean (Marlon Wayans), a man about whom we'll never learn very much, presumably because there isn't much to learn. In a stunning cut that is a stark reminder of how timid and shitty most contemporary filmmaking is with story structure, we move from the newlyweds in the full flush of horny infatuation right to a point in time when they already have a toddler, and before we're able to get our bearings, the toddler has become a schoolkid, with a younger sister as well. It's enough to give you the best kind of whiplash, embodying just in its almost bland editing the feeling of waking up and realising that ten years have gone by and what do you even have to show for it? And now Laura is just a few months shy of 40, and in one last unstressed bit of storytelling-through-structure, the action slows down to a glacial crawl, setting up a nimble contrast between how crazy fast a decade can go by despite every single day feeling like it crawls past over an eternity.

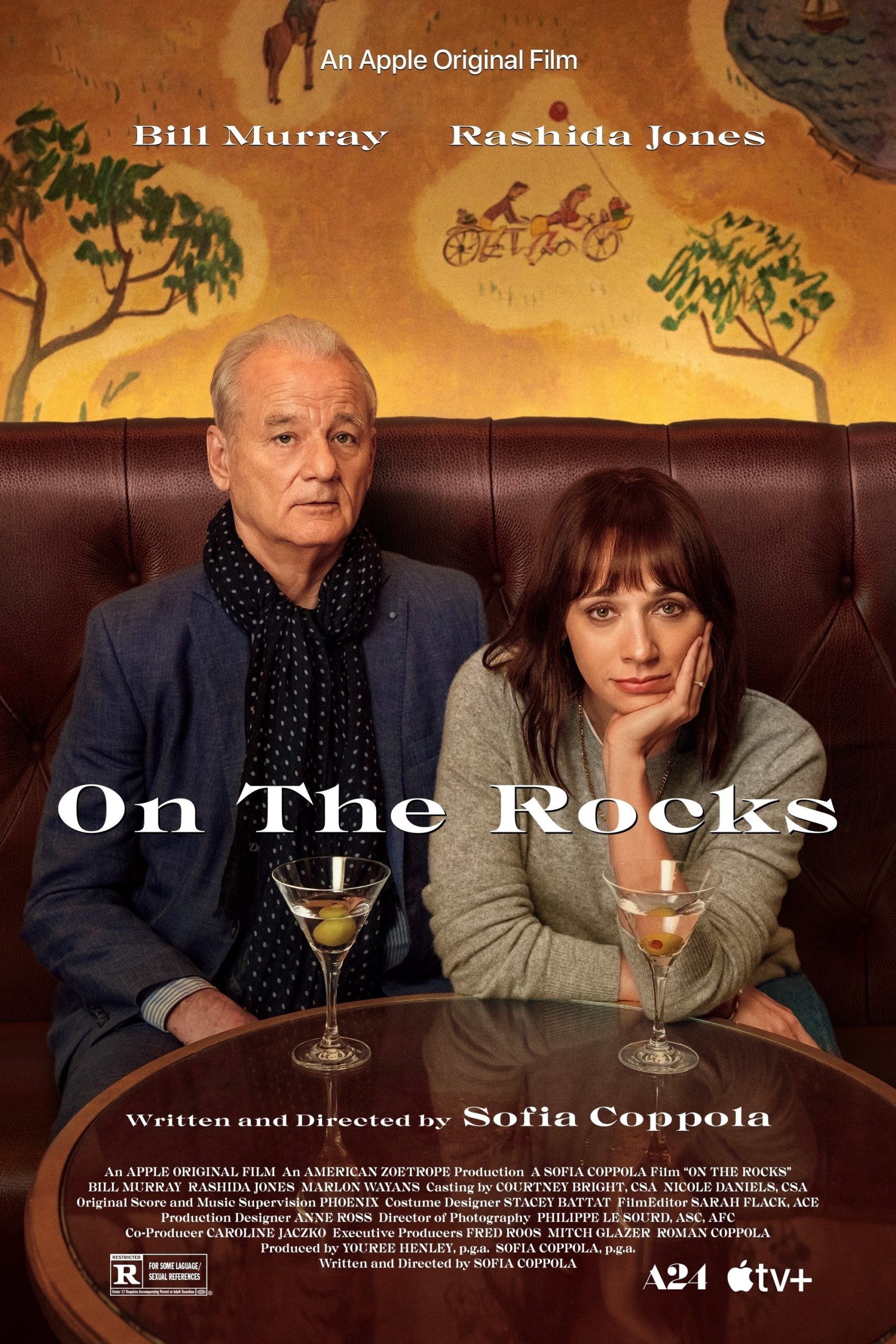

And this is depicted in a couple ways: repeated scenes shot from repeated angles, with repeated comic beats (the film builds itself along a motif of Laura standing in line to pick up the kids from school next to the prattling, droning Vanessa, played by Jenny Slate as a perfect embodiment of bourgeois affectations orbiting a profound vacuum of personality), interspersed amongst conversations that do nothing and go nowhere. Call it boring and redundant, if you prefer; for me, Jones's exhaustion in the role, not playing a woman at the end of her tether so much as a woman who is learning anew every day just how much goddamn tether she still has to play out, makes every single scene of the film at least engaging on the level of character beats, even if the story is basically lying there like a fish at the bottom of a boat. Eventually, she lands upon a suspicion that Dean is cheating on her, and it seems awfully possible that she doesn't altogether believe that he is, and maybe doesn't even care if he is, but is just grateful to have something to provide the possibility for drama in her life. Which is presumably also why she makes the self-evidently wrong decision to look for advice from her legendary womaniser of a father, Felix (Bill Murray), a charismatic sexist who decides instantly that she's right about Dean, and starts helping her concoct a plan to prove it.

The bulk of the film is built around letting Jones and Murray orbit each other - not playing off of each other, really, which is part of the delight. Jones turns Laura's annoyance with Felix's loutish ways up pretty high pretty fast, and so she spends the whole movie trafficking in exasperated reaction shots, while Murray (in a role that isn't challenging him much at all, though he still appears to be enjoying it) plays Felix as someone whose main enjoyment in life his hearing his own witty words and delighting in his own breezy charm, and so much the better if he gets to gesture in the direction of patching up a strained relationship with his daughter. And to the credit of both actors, the relationship between Laura and Felix seems real, and worth patching up; it's unhealthy and all, or we wouldn't have a narrative, but it's clearly founded on a core of genuine affection that flows both ways, in the way one can love a relative while also finding them exhausting and irritating company for good and petty reasons.

Thankfully, this isn't a film about how two misfits learn about each other, hug, and make up; it is Laura's movie, not Laura and Felix's movie, and it is unsentimental about the fact that she has suffered from her dad's glib way of inhabiting the world, even if she's probably better with him in her life than not. The problems of an impulsive dad who's clearly trying to impress her with how much zany, endearing fun he can be as he helps her zip around New York, stalking Dean, are folded into the whole array of things that are making Laura's life frustrating. This is all played for low-key humor and shaggy hang-out realism rather than the uncertain, awkward melancholy and slightly dreamy quality of Coppola's best films, and perhaps because it's reflecting middle-aged pragmatism rather than the the passions of young adults or adolescents, it doesn't have much feeling of urgency, nor any sense of this being a weighty story of profound psychological depth. It's just a light, generous sketch of a well-written and well-played character beautifully shot and patiently paced; a small work, but pristine.

On the Rocks is a little bit about how tiring it is to be the daughter of a celebrated father (thus Somewhere) and a little bit about how tiring it is to have an emotionally distant husband who is very nice in a detached way as he leaves you alone in a glamorous, glossy apartment (thus Lost in Translation, which I imagine remains Coppola's most highly-regarded film), and a little bit about shiny surfaces that don't have much to them beneath the shine (Coppola is working with cinematographer Philippe Le Sourd again after their magnificent collaboration on the 2017 version of The Beguiled, and he makes New York at night sparkle like a black diamond), and really a little bit about a lot of things. All these things center upon Laura (Rashida Jones, herself a daughter of a world-renowned father in his own medium), who we meet on the day of her wedding to Dean (Marlon Wayans), a man about whom we'll never learn very much, presumably because there isn't much to learn. In a stunning cut that is a stark reminder of how timid and shitty most contemporary filmmaking is with story structure, we move from the newlyweds in the full flush of horny infatuation right to a point in time when they already have a toddler, and before we're able to get our bearings, the toddler has become a schoolkid, with a younger sister as well. It's enough to give you the best kind of whiplash, embodying just in its almost bland editing the feeling of waking up and realising that ten years have gone by and what do you even have to show for it? And now Laura is just a few months shy of 40, and in one last unstressed bit of storytelling-through-structure, the action slows down to a glacial crawl, setting up a nimble contrast between how crazy fast a decade can go by despite every single day feeling like it crawls past over an eternity.

And this is depicted in a couple ways: repeated scenes shot from repeated angles, with repeated comic beats (the film builds itself along a motif of Laura standing in line to pick up the kids from school next to the prattling, droning Vanessa, played by Jenny Slate as a perfect embodiment of bourgeois affectations orbiting a profound vacuum of personality), interspersed amongst conversations that do nothing and go nowhere. Call it boring and redundant, if you prefer; for me, Jones's exhaustion in the role, not playing a woman at the end of her tether so much as a woman who is learning anew every day just how much goddamn tether she still has to play out, makes every single scene of the film at least engaging on the level of character beats, even if the story is basically lying there like a fish at the bottom of a boat. Eventually, she lands upon a suspicion that Dean is cheating on her, and it seems awfully possible that she doesn't altogether believe that he is, and maybe doesn't even care if he is, but is just grateful to have something to provide the possibility for drama in her life. Which is presumably also why she makes the self-evidently wrong decision to look for advice from her legendary womaniser of a father, Felix (Bill Murray), a charismatic sexist who decides instantly that she's right about Dean, and starts helping her concoct a plan to prove it.

The bulk of the film is built around letting Jones and Murray orbit each other - not playing off of each other, really, which is part of the delight. Jones turns Laura's annoyance with Felix's loutish ways up pretty high pretty fast, and so she spends the whole movie trafficking in exasperated reaction shots, while Murray (in a role that isn't challenging him much at all, though he still appears to be enjoying it) plays Felix as someone whose main enjoyment in life his hearing his own witty words and delighting in his own breezy charm, and so much the better if he gets to gesture in the direction of patching up a strained relationship with his daughter. And to the credit of both actors, the relationship between Laura and Felix seems real, and worth patching up; it's unhealthy and all, or we wouldn't have a narrative, but it's clearly founded on a core of genuine affection that flows both ways, in the way one can love a relative while also finding them exhausting and irritating company for good and petty reasons.

Thankfully, this isn't a film about how two misfits learn about each other, hug, and make up; it is Laura's movie, not Laura and Felix's movie, and it is unsentimental about the fact that she has suffered from her dad's glib way of inhabiting the world, even if she's probably better with him in her life than not. The problems of an impulsive dad who's clearly trying to impress her with how much zany, endearing fun he can be as he helps her zip around New York, stalking Dean, are folded into the whole array of things that are making Laura's life frustrating. This is all played for low-key humor and shaggy hang-out realism rather than the uncertain, awkward melancholy and slightly dreamy quality of Coppola's best films, and perhaps because it's reflecting middle-aged pragmatism rather than the the passions of young adults or adolescents, it doesn't have much feeling of urgency, nor any sense of this being a weighty story of profound psychological depth. It's just a light, generous sketch of a well-written and well-played character beautifully shot and patiently paced; a small work, but pristine.