Spider, spider, burning bright

The biggest problem that was always going to face Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse is that it was never going to have the staggering shock of the truly new and revolutionary. Even if the first sequel to 2018's Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse were to have a story more expansive and elaborate than that film (and it does), and to tell that story with a more technically complex style with a broader array of stylistic reference points (and it does), it would never quite be able to shake the feeling that these things are now expected. That's not fair, but so little in the world is.

At any rate, Across the Spider-Verse is absolutely, unquestionably "bigger" than Into the Spider-Verse. The burning question is whether it is "better" than Into the Spider-Verse, and I'm pretty comfortable in saying that it isn't. That was, of course, always going to be an extraordinary high bar to clear: Into the Spider-Verse is among the best (I would say, the best) comic book adaptations ever made, and among the most aesthetically radical (I would say the most aesthetically radical) computer-animated feature films of the 2010s. In its story of how a random Brooklyn teenager, Miles Morales (Shameik Moore), came to possess the powers of a radioactive spider, and learned that thousands of other spider-heroes existed in thousands of parallel universes, and furthermore came to learn how to use his powers in service to do good and noble things, while also freeing himself from the surly bounds of Earth, it captures a sense of limitless possibility and pure weightless joy that no other superhero movie before it had ever come close to managing in all the many years since Christopher Reeve made us believe that a man could fly. To its great credit, Across the Spider-Verse has no interest in simply doing more of the same: like all the very best superhero sequels, it trusts that the "what" and "how" have been sufficiently pinned down already, so now its job is to go on and do something else. I am, to be honest, not sure that the "something else" worked out: while Across the Spider-Verse unquestionably has a busier story, with more layers, I think there's something that's just more satisfying about the clean, elemental character arc and laser-focused emotional appeal of the first movie. The difference, I guess, is that Into the Spider-Verse transported me with awe, while Across the Spider-Verse, no matter how world-class awesome it gets, pretty much just left me sitting there.

It assuredly doesn't help that Across the Spider-Verse was made alongside its own sequel, 2024's Spider-Man: Beyond the Spider-Verse, and with that guarantee locked in place, the film's writers - Phil Lord & Christopher Miller and Dave Callaham (Lord had a credit on the first movie as well, and Miller undoubtedly contributed elements to it; Callaham is a newcomer to the series) - off-loaded a lot of the storytelling work to that film. This is the other candidate for "biggest problem": Across the Spider-Verse quite literally isn't telling a complete story. Not in the standard "two films made in the same production block" way where it wraps up this conflict and then plants the hook for the next film all in one smooth movement. In the way where it gets about two-thirds of the way through its rising action and then slams on the breaks, shouts "okay, cool everybody, see you in ten months!" and leaps into the credits. There is a very real sense in which it is not possible for Across the Spider-Verse even can be "satisfying", because it has not, as yet, gestured towards offering us any satisfaction, except in that it somewhat loosely structures itself around the character arc of its most prominent side character, Gwen "Spider-Woman" Stacy (Hailee Steinfeld), and while even her story has a generous number of loose ends dangling off of it, her thorny relationship with her dad (Shea Whigham), a cop trying to arrest Spider-Woman for murder, does feels like it's resolved enough that you can sort of use it as the excuse to argue that Across the Spider-Verse does actually have some kind of shape.

Setting aside the question of whether Beyond the Spider-Verse will actually stick the landing of this three-quarters-of-a-story (there seems to be absolutely no reason to doubt the care and vision already expressed by this creative team, so my assumption is that they will; on the other hand, I was pretty optimistic about The Dark Knight Rises before it opened), I'll admit that I just don't find the story, even the best-executed complete version of it, to be as interesting as the one from Into the Spider-Verse, and certainly not as emotionally engaging. The actual plot meat-and-potatoes of Across the Spider-Verse is pretty straightforward, for something that runs to 141 minutes (and unquestionably shouldn't, though this is also something where 10 different people would probably offer 15 different suggestions for exactly what 20 minutes needs to go): Miles has been very lonely for all his spider-friends from the first movie, especially Gwen, and wants to figure out how to re-open the multiverse to visit them. Gwen, meanwhile, has had a terrible fight with her cop dad (Shea Whigham), who tried to put her under arrest after he learned that she was Spider-Woman, and has now joined an elite multiversal fighting force of seemingly all of the thousands of different Spider-People, fighting to preserve the multiverse from collapse. And there's an especially bad weak point in Miles's universe, since the events of the first movie led to the creation of The Spot (Jason Schwartzman), a pathetic excuse for a supervillain whose very body is a transdimensional object. She's assigned to stop this new threat, and decides there can be no harm in popping by to say hi to Miles, who thus finds out about all of this complicated Spider-Lore, and badly wants to join the same. Unfortunately, the head of the Spider-Corps, Spider-Man 2099 (Oscar Isaac), has reason to assume that Miles himself is one of the most dangerous threats to the integrity of the multiverse.

And then... see you in 2024, mostly, though a lot of things do get more or less get to a point where it seems pretty clear how they might resolve, maybe even probably will resolve. What we've already got is sufficient to do two main things. Story-wise, the thing is to begin the process of indulging in a meta-commentary on what it means to have a Spider-Man movie when there has already been such an enormous quantity of Spider-Man media (several different films and TV shows starring versions of the character get quick cameos), and what it means to tell a story using this character, and particularly what it means to tell a story using this character when you have various executives, editors, and hair-trigger online fans all with their own very concrete ideas of what "a Spider-Man story" can and/or must include. Compared to the much simpler meta-commentary in Into the Spider-Verse, which was mostly about what it means to read comic books and see yourself reflected in them, none of this feels very... humane, I guess is the word. Maybe it's just that I care less. But the first movie tapped into the awe of letting your imagination run wild, and this feels like its interests don't extend beyond picking fights on Twitter. We'll just have to see what 2024 brings.

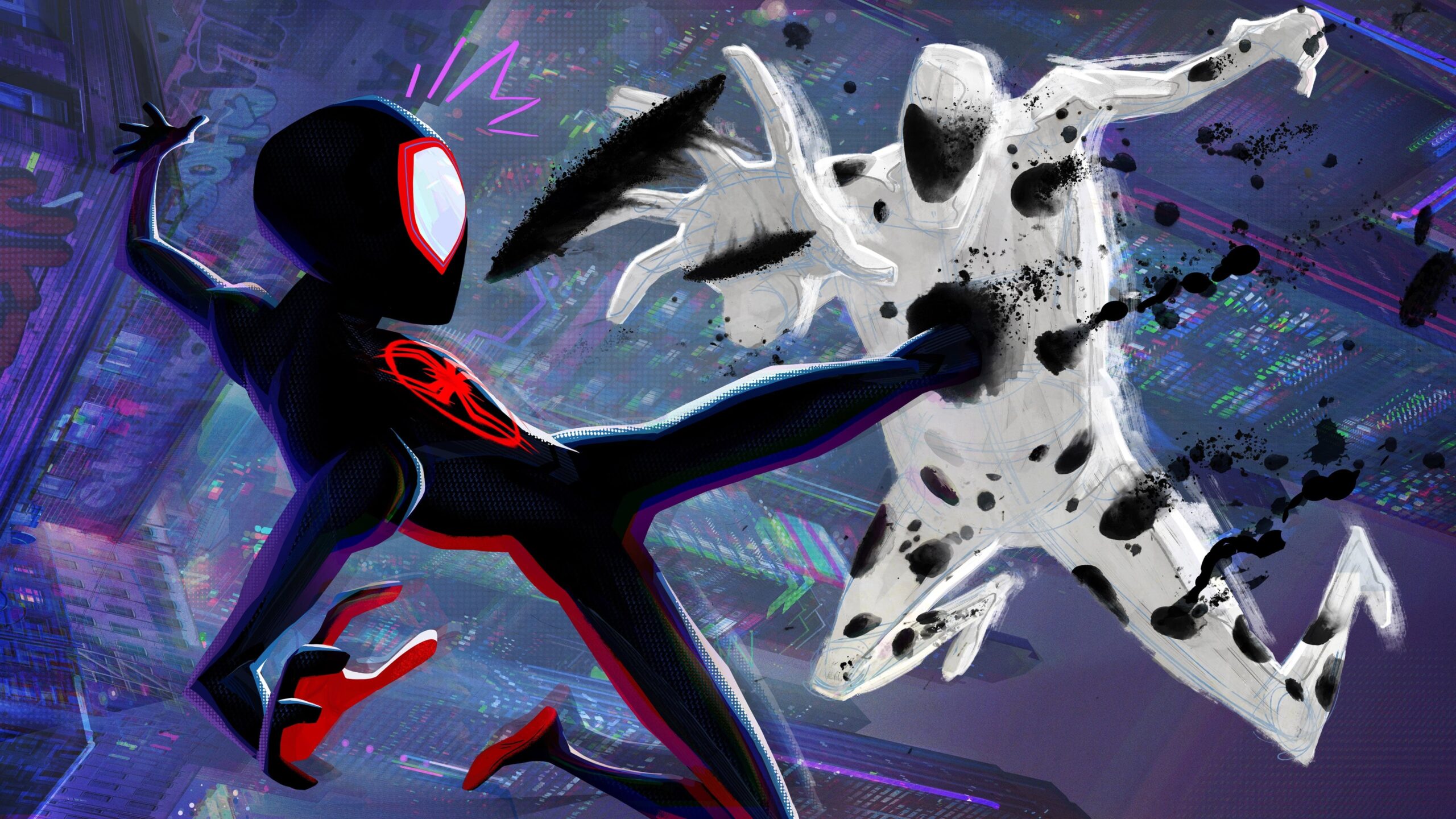

We do not, however, need to wait for 2024 to get the absolute jaw-dropping triumph of animation represented by Across the Spider-Verse, an extravagant blend of styles and visual ideas and techniques that makes the bleeding-edge radicalism of the 2018 film seem downright boring. This is the other thing that the great big sprawling multiverse concept gives us: a functionally infinite universe to play in. And unlike most recent multiverse pictures (a phrase that makes me tired just typing it out), Across the Spider-Verse is treating the notion of multiple universes as a great responsibility, if you will, something that makes a promise to the viewer, that we'll see a truly wide and varied array of possible realities, not just "our reality, but people wear shoes on their hands". For starters, Across the Spider-Verse begins with the notion that different universes adapted from a long-running comic book franchise should look to all the different kinds of comic book aesthetics that have existed in Spider-Man's decades-long history. And I do mean begins with that notion. Even the studio logos are drawn to resemble what those company icons might have looked like over a number of years in several different media, and once the film properly begins, it introduces us to Gwen's own universe, where everything has the scuffy, smeary brush work of a watercolor painting. So much so that I didn't really realise until finishing that sentence that I'd used the phrase "brush work" to describe something that exists only as a series of instructions in a computer for how to scatter light (which also only exists as a set of instructions in a computer). There's a hazy, almost fanciful feeling to it, something ready to back off and go into Impressionistic fields of lighter and dark colors rather than realistically depict spaces, growing more abstract the more intense the emotional conflict between daughter and father grows. It's not the last painterly aesthetic the film trots out, either, as it bookends this with some gorgeous end credits that feel sort of like if the James Bond credits sequences were modeled on oil paintings.

In between these two classy painterly modes, we get such an unrelenting onslaught of styles. Probably not everything, though I am tempted by that word. It's all your standard 3-D CGI models being moved in 3-D CGI spaces, but they've been painted and textured with a seemingly inexhaustible number of options drawn from comic books, but also the broader world of graphic art. The first fight scene pits the oil painting Gwen against a version of the villain Vulture drawn in faded umber ink on ancient paper (he's meant to look like a living version of an illustration from the notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci), and this ends up proving to be more of an attempt to train us on something easy than it is an early attempt to show off by hauling out the big guns. I think if you were to do nothing while watching Across the Spider-Verse other than try to catalogue every different aesthetic that shows up and figure out what it's in reference to, you'd still have a pretty big job on your hands. I would be doing none of you a service by digging into this too terribly far (the most I laughed at any joke in the entire film was at the appearance of a particular animation style that I was completely unprepared to see pop up for a couple of shots), but it's a wondrous collage of different approaches crammed together in one frame, with not just the textures but the color palettes and lighting and the amount of "3-D-ness" carefully managed for every single character. It's maximalism of the most exhausting kind, in a great and thrilling way

Hand-in-hand with the above, having access to every possible Spider-Man concept means that the the filmmakers can keep whipping out surprises and new ideas right up until it ends. If I were to temper my enthusiasm, it would be only by saying that, compared to Into the Spider-Verse, this is going more for quantity than quality: there's nothing here as well-developed and funny as Nicolas Cage's Spider-Man Noir and John Mulvaney's Spider-Ham (the film is, in general, less funny than the first one, and as it goes along, it grows increasingly clear that "funny" isn't really much of a top priority). This one is more about quick hits of "boy, wasn't THAT weird?" absurdist humor than letting something offbeat evolve slowly into something ridiculous. Still, it absolutely means that Across the Spider-Verse never comes within a mile of being boring: it's impressive how something this long can hit the finish line without having ever really repeated itself or stretched a bit out longer than it needed to go. There are moments of tranquility, moments of wild kineticism, moments of zany humor, moments that both do the grim work of franchise "world-building" (every previous cinematic universe involving Spider-Man characters gets a shout-out) and lightly make fun of the whole idea of franchises. Where the film pulls all of this from, I can't say; what it could possibly have left for the third film, I also can't say. But we are watching some incredibly imaginative kids playing in an enormous sandbox, and even if this taxes those imaginations to the limits, those limits are way, way the hell out there.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

If you enjoyed this article, why not support Alternate Ending as a recurring donor through Patreon, or with a one-time donation via Paypal? For just a dollar a month you can contribute to the ongoing health of the site, while also enjoying several fun perks!

At any rate, Across the Spider-Verse is absolutely, unquestionably "bigger" than Into the Spider-Verse. The burning question is whether it is "better" than Into the Spider-Verse, and I'm pretty comfortable in saying that it isn't. That was, of course, always going to be an extraordinary high bar to clear: Into the Spider-Verse is among the best (I would say, the best) comic book adaptations ever made, and among the most aesthetically radical (I would say the most aesthetically radical) computer-animated feature films of the 2010s. In its story of how a random Brooklyn teenager, Miles Morales (Shameik Moore), came to possess the powers of a radioactive spider, and learned that thousands of other spider-heroes existed in thousands of parallel universes, and furthermore came to learn how to use his powers in service to do good and noble things, while also freeing himself from the surly bounds of Earth, it captures a sense of limitless possibility and pure weightless joy that no other superhero movie before it had ever come close to managing in all the many years since Christopher Reeve made us believe that a man could fly. To its great credit, Across the Spider-Verse has no interest in simply doing more of the same: like all the very best superhero sequels, it trusts that the "what" and "how" have been sufficiently pinned down already, so now its job is to go on and do something else. I am, to be honest, not sure that the "something else" worked out: while Across the Spider-Verse unquestionably has a busier story, with more layers, I think there's something that's just more satisfying about the clean, elemental character arc and laser-focused emotional appeal of the first movie. The difference, I guess, is that Into the Spider-Verse transported me with awe, while Across the Spider-Verse, no matter how world-class awesome it gets, pretty much just left me sitting there.

It assuredly doesn't help that Across the Spider-Verse was made alongside its own sequel, 2024's Spider-Man: Beyond the Spider-Verse, and with that guarantee locked in place, the film's writers - Phil Lord & Christopher Miller and Dave Callaham (Lord had a credit on the first movie as well, and Miller undoubtedly contributed elements to it; Callaham is a newcomer to the series) - off-loaded a lot of the storytelling work to that film. This is the other candidate for "biggest problem": Across the Spider-Verse quite literally isn't telling a complete story. Not in the standard "two films made in the same production block" way where it wraps up this conflict and then plants the hook for the next film all in one smooth movement. In the way where it gets about two-thirds of the way through its rising action and then slams on the breaks, shouts "okay, cool everybody, see you in ten months!" and leaps into the credits. There is a very real sense in which it is not possible for Across the Spider-Verse even can be "satisfying", because it has not, as yet, gestured towards offering us any satisfaction, except in that it somewhat loosely structures itself around the character arc of its most prominent side character, Gwen "Spider-Woman" Stacy (Hailee Steinfeld), and while even her story has a generous number of loose ends dangling off of it, her thorny relationship with her dad (Shea Whigham), a cop trying to arrest Spider-Woman for murder, does feels like it's resolved enough that you can sort of use it as the excuse to argue that Across the Spider-Verse does actually have some kind of shape.

Setting aside the question of whether Beyond the Spider-Verse will actually stick the landing of this three-quarters-of-a-story (there seems to be absolutely no reason to doubt the care and vision already expressed by this creative team, so my assumption is that they will; on the other hand, I was pretty optimistic about The Dark Knight Rises before it opened), I'll admit that I just don't find the story, even the best-executed complete version of it, to be as interesting as the one from Into the Spider-Verse, and certainly not as emotionally engaging. The actual plot meat-and-potatoes of Across the Spider-Verse is pretty straightforward, for something that runs to 141 minutes (and unquestionably shouldn't, though this is also something where 10 different people would probably offer 15 different suggestions for exactly what 20 minutes needs to go): Miles has been very lonely for all his spider-friends from the first movie, especially Gwen, and wants to figure out how to re-open the multiverse to visit them. Gwen, meanwhile, has had a terrible fight with her cop dad (Shea Whigham), who tried to put her under arrest after he learned that she was Spider-Woman, and has now joined an elite multiversal fighting force of seemingly all of the thousands of different Spider-People, fighting to preserve the multiverse from collapse. And there's an especially bad weak point in Miles's universe, since the events of the first movie led to the creation of The Spot (Jason Schwartzman), a pathetic excuse for a supervillain whose very body is a transdimensional object. She's assigned to stop this new threat, and decides there can be no harm in popping by to say hi to Miles, who thus finds out about all of this complicated Spider-Lore, and badly wants to join the same. Unfortunately, the head of the Spider-Corps, Spider-Man 2099 (Oscar Isaac), has reason to assume that Miles himself is one of the most dangerous threats to the integrity of the multiverse.

And then... see you in 2024, mostly, though a lot of things do get more or less get to a point where it seems pretty clear how they might resolve, maybe even probably will resolve. What we've already got is sufficient to do two main things. Story-wise, the thing is to begin the process of indulging in a meta-commentary on what it means to have a Spider-Man movie when there has already been such an enormous quantity of Spider-Man media (several different films and TV shows starring versions of the character get quick cameos), and what it means to tell a story using this character, and particularly what it means to tell a story using this character when you have various executives, editors, and hair-trigger online fans all with their own very concrete ideas of what "a Spider-Man story" can and/or must include. Compared to the much simpler meta-commentary in Into the Spider-Verse, which was mostly about what it means to read comic books and see yourself reflected in them, none of this feels very... humane, I guess is the word. Maybe it's just that I care less. But the first movie tapped into the awe of letting your imagination run wild, and this feels like its interests don't extend beyond picking fights on Twitter. We'll just have to see what 2024 brings.

We do not, however, need to wait for 2024 to get the absolute jaw-dropping triumph of animation represented by Across the Spider-Verse, an extravagant blend of styles and visual ideas and techniques that makes the bleeding-edge radicalism of the 2018 film seem downright boring. This is the other thing that the great big sprawling multiverse concept gives us: a functionally infinite universe to play in. And unlike most recent multiverse pictures (a phrase that makes me tired just typing it out), Across the Spider-Verse is treating the notion of multiple universes as a great responsibility, if you will, something that makes a promise to the viewer, that we'll see a truly wide and varied array of possible realities, not just "our reality, but people wear shoes on their hands". For starters, Across the Spider-Verse begins with the notion that different universes adapted from a long-running comic book franchise should look to all the different kinds of comic book aesthetics that have existed in Spider-Man's decades-long history. And I do mean begins with that notion. Even the studio logos are drawn to resemble what those company icons might have looked like over a number of years in several different media, and once the film properly begins, it introduces us to Gwen's own universe, where everything has the scuffy, smeary brush work of a watercolor painting. So much so that I didn't really realise until finishing that sentence that I'd used the phrase "brush work" to describe something that exists only as a series of instructions in a computer for how to scatter light (which also only exists as a set of instructions in a computer). There's a hazy, almost fanciful feeling to it, something ready to back off and go into Impressionistic fields of lighter and dark colors rather than realistically depict spaces, growing more abstract the more intense the emotional conflict between daughter and father grows. It's not the last painterly aesthetic the film trots out, either, as it bookends this with some gorgeous end credits that feel sort of like if the James Bond credits sequences were modeled on oil paintings.

In between these two classy painterly modes, we get such an unrelenting onslaught of styles. Probably not everything, though I am tempted by that word. It's all your standard 3-D CGI models being moved in 3-D CGI spaces, but they've been painted and textured with a seemingly inexhaustible number of options drawn from comic books, but also the broader world of graphic art. The first fight scene pits the oil painting Gwen against a version of the villain Vulture drawn in faded umber ink on ancient paper (he's meant to look like a living version of an illustration from the notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci), and this ends up proving to be more of an attempt to train us on something easy than it is an early attempt to show off by hauling out the big guns. I think if you were to do nothing while watching Across the Spider-Verse other than try to catalogue every different aesthetic that shows up and figure out what it's in reference to, you'd still have a pretty big job on your hands. I would be doing none of you a service by digging into this too terribly far (the most I laughed at any joke in the entire film was at the appearance of a particular animation style that I was completely unprepared to see pop up for a couple of shots), but it's a wondrous collage of different approaches crammed together in one frame, with not just the textures but the color palettes and lighting and the amount of "3-D-ness" carefully managed for every single character. It's maximalism of the most exhausting kind, in a great and thrilling way

Hand-in-hand with the above, having access to every possible Spider-Man concept means that the the filmmakers can keep whipping out surprises and new ideas right up until it ends. If I were to temper my enthusiasm, it would be only by saying that, compared to Into the Spider-Verse, this is going more for quantity than quality: there's nothing here as well-developed and funny as Nicolas Cage's Spider-Man Noir and John Mulvaney's Spider-Ham (the film is, in general, less funny than the first one, and as it goes along, it grows increasingly clear that "funny" isn't really much of a top priority). This one is more about quick hits of "boy, wasn't THAT weird?" absurdist humor than letting something offbeat evolve slowly into something ridiculous. Still, it absolutely means that Across the Spider-Verse never comes within a mile of being boring: it's impressive how something this long can hit the finish line without having ever really repeated itself or stretched a bit out longer than it needed to go. There are moments of tranquility, moments of wild kineticism, moments of zany humor, moments that both do the grim work of franchise "world-building" (every previous cinematic universe involving Spider-Man characters gets a shout-out) and lightly make fun of the whole idea of franchises. Where the film pulls all of this from, I can't say; what it could possibly have left for the third film, I also can't say. But we are watching some incredibly imaginative kids playing in an enormous sandbox, and even if this taxes those imaginations to the limits, those limits are way, way the hell out there.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

If you enjoyed this article, why not support Alternate Ending as a recurring donor through Patreon, or with a one-time donation via Paypal? For just a dollar a month you can contribute to the ongoing health of the site, while also enjoying several fun perks!