Summer of Blood: Hellfire

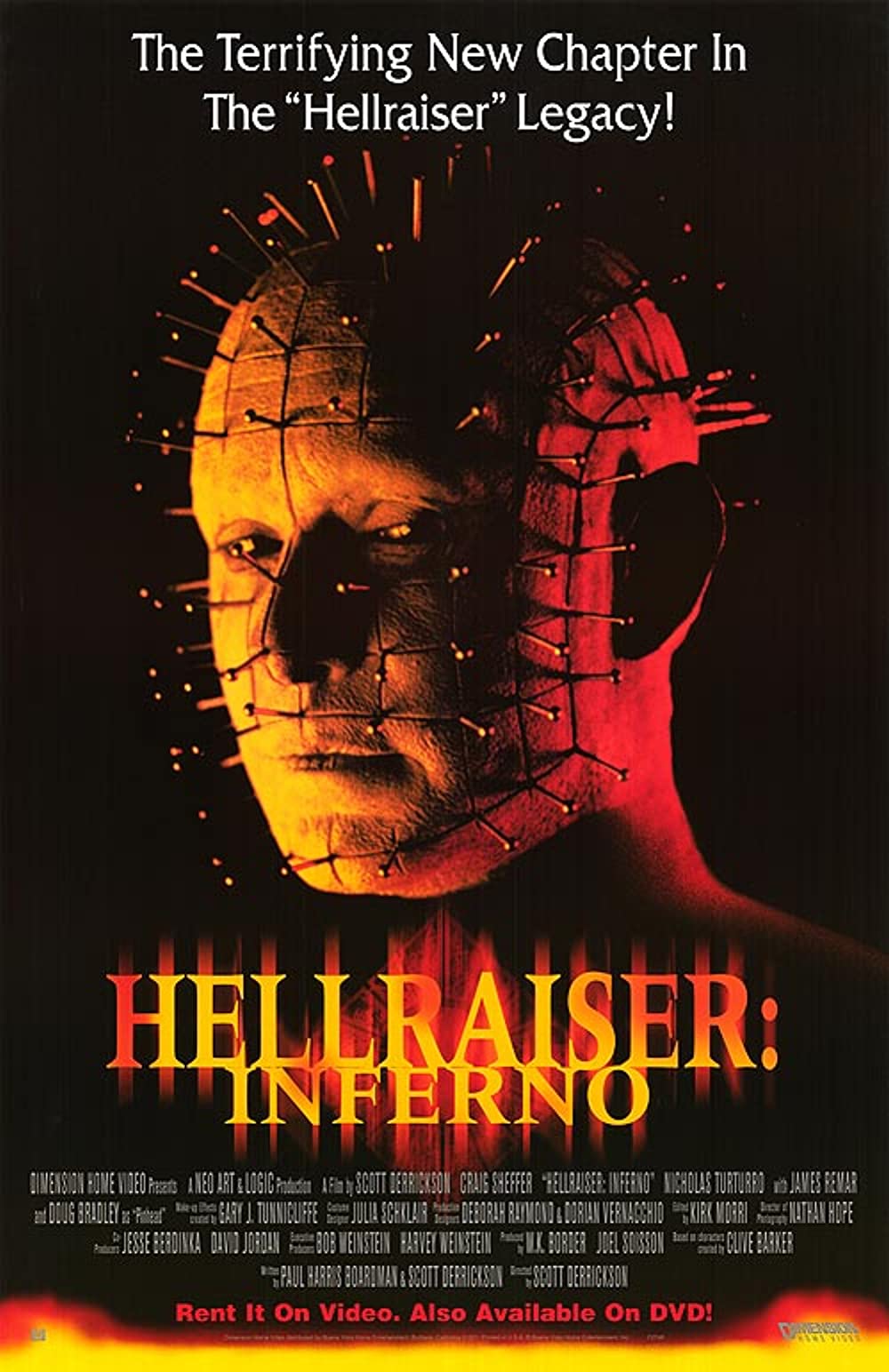

Among those people invested enough in the ongoing development of the Hellraiser franchise for such issues to matter, the direct-to-video era of the franchise that started in the year 2000 - four years after the last theatrical release, the much-disliked whipping boy Hellraiser: Bloodline - is also accused of being the "we just stuck Pinhead in an unrelated script that was lying around the Dimension Films offices" era, and it is not entirely clear to me that this is fair. Take, for example, the case of Hellraiser: Inferno, the fifth film overall in the franchise, and the one that inaugurated its DTV epoch. It is true that Doug Bradley (the actor who plays that most viscerally iconic '80s movie killer here, and had done so in all four earlier films stretching back to Hellraiser in 1986), claimed that this movie was an original script that had been retrofitted into a Hellraiser movie. And he would probably know. But it is also true that Scott Derrickson, the director and co-writer, has said that's just nonsense, he & co-writer Paul Harris Boardman were invited to pitch a new Hellraiser and this is what they pitched, and they wrote it to order. And he would definitely know, though if we want to be unduly cynical, he would also likely have a stronger incentive to lie about this than Bradley.

That being said, even if we accept the best-case version of the film's writing history - that it was born and bred to be the fifth Hellraiser movie and never anything but - we're still stuck with "so it was purpose-built to go in this franchise, and it's this fucking bad at it?" Maybe it's even more comforting to assume it was a patch-up job. Hellraiser: Inferno may or may not be a good standalone horror movie - I am inclined more towards "or may not" - but it's a broken-down catastrophe as a Hellraiser picture, flushing every of the weird and kinky and troubling philosophy underpinning even the very worst of the theatrically-released films that preceded it. Pinhead has up till now been both a morally unfathomable emblem of the desire for extreme sensory input at all cost, and an angry slashy-movie psychopath, and those are already two very different things to square; Inferno wants him to be "spiritual judge in an all but explicitly Christian moral universe", and I mean 90% of the point of these is that they are very obviously not Christian. Derrickson, however, is Christian, or at least he plays one at the movies (subsequent to this film, during his largely undeserved ongoing career in big studio features, he's directed two explicitly Christian horror films, 2005's The Exorcism of Emily Rose and 2014's Deliver Us from Evil), which isn't a problem as such, except that he seems to have gotten hung up on an extremely literal meaning of "hell" that's not compatible with the one the series had used up till this point, and much less interesting and complicated as well.

Even so, Inferno is better than Bloodline, and it is way the hell better than the 1992 Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth, because complain as much as I like, the Hellraisers were more than able to fuck up the basics long before they went direct to video. Derrickson isn't a director I care for very much, but it's still readily apparent that he had more than it took to make cheapie sludge like this. One could go so far as to accuse him of overdirecting the movie, I would even say, which is a pretty small and inconsequential insult as far as direct-to-video horror goes. Most of these sorts of movies barely feel directed at all; there might be points where Derrickson's unfocused "look at me! look what I can do!" showmanship gets tiresome, but it's got an aesthetic personality and something not unlike a decent budget to carry it off (I mean, the film was still cheap, at a reported $2 million, but not by DTV standards).

And I don't want to undersell that it is tiresome, in places. There's an early moment where our lead antihero, corrupt cop Joseph Thorne (Craig Sheffer, who had previously been involved with films based on author Clive Barker's writings when he starred in 1990's Nightbreed) comes home to his longsuffering wife (Noelle Evans) and daughter (Lindsay Taylor) - this is the kind of film that doesn't even briefly suppose that the antihero cop's wife needs any descriptive adjectives other than "longsuffering" - and registers a moment of tenderness towards the child by setting his cheek against her sleeping face. And for this shot, the camera rotates ninety degrees to lie on its side, so that Joe's head is pointing down and the daughter's head is pointing up, and the bed makes the right side of the frame. It's extremely fussy and while, in light of where the film ends up going, you can stretch so hard to come up with a dubious meaning about how he's facing down to hell and she's looking up towards heaven, or something equally symbolic, but it's mostly just a strange stylistic gesture that calls a hell of a lot attention to itself for no good reason.

At least the other directorial overreaching is generally in service of making this more X-treme or intense or whatnot. The one that leaps to mind, which also comes early on, is when Joe has gone to his favorite prostitute (and now we start to see why he is an antihero, and why his wife is longsuffering), and she drops slowly down out of the frame to give him a blow job, a standard enough shot, at which the frame fades to red. Then it fades back in to a sex scene that has been so overexposed that he basically only see vague patches of shadow representing the human face in the field of bleached-out white. Again, it doesn't really do much, but at least creates a kind of heightened... something. "This movie fucks, and it's ugly, because humanity is ugly!" That kind of thing. I guess.

Other little random spurts of high style come and go - there's a dingy rural-looking bar with neon lights hanging on its outside walls that could not possibly flag its complete debt to Twin Peaks any harder, for example, and it's apparent (though less shameless) in a few other places that Derrickson knows his David Lynch - but for the most part, Hellraiser: Inferno quickly settles into a very clear stylistic groove, and that groove's name is "violent crime horror released in the wake of Se7en". It might even be more specifically "in the wake of the post-Se7en television crime series Millennium", given the particularly occult and torture-centric vision of human depravity that Inferno builds its mystery around: Joe has been put case of ritualistic serial murders where the bodies have been subject to some kind of horrible torment and mortification, and every crime scene includes a finger that has been chopped off of a human child's hand.

At the first of these, he also finds a small filigreed box, our good friend the Lament Configuration - which is given that name in dialogue, making it I believe the first Hellraiser movie to make that name text - and of course he immediately starts poking at it and causes it to open. Immediately following this, Joe starts to have strange visions of horrific violence that later turns out to come to pass, as well as seeing two women (Lynn Speier, Trisha Kara) who have been identically mutilated in elaborate, ritualistic-looking ways. Soon enough, Joe has connected the murders to a shadowy figure know as The Engineer (a name from barker's novella The Hellbound Heart, from which this franchise ultimately derives; it meant something very different there), and at the same time, the Engineer's MO changes, so that by chance or design, he's only killing people Joe personally knows.

None of this has much of anything to do with Hellraiser, and it will have even less to do with Hellraiser as it enters its third act and we start to learn just what evil Joe actually unleashed when he solved that puzzle box, but I think we can err on the side of charity and overlook that. After all, if having anything to do with Hellraiser gets us Hell on Earth, we're well rid of it. Taken solely on its own terms as a psychology horror mystery about a dirty cop and all-around shitty person being forced to look at the cruelty of the world as a reflection of his own awful behavior, Inferno isn't terrible. It's got some pretty significant problems, of which the most persistent is Sheffer's performance: he's being hammy and over the top in his performance of a gruff "mean asshole", lowering his eyes to glower all the time and clenching his teeth so hard it's a wonder they don't shatter, and keeping his mouth locked into big frown, almost more like a pouty child than anything else.

It's a pretty flimsy, unconvincing lead performance, and it has a major negative effect on a film whose overall strategy is entirely based on the filmmakers' ability to create a convincing mood of brutal moral decay; it's a severe and serious movie with a goofy mock-serious dead weight in its center, around whom virtually everything else in the entire movie pivots. But let us give Inferno credit where it is due: Derrickson and his crew have done a fairly good job at recycling that "1990s nihilism chic" aesthetic, creating a movie whose heavy atmosphere might have been done better elsewhere, but it has a heavy atmosphere, and that's more than either Hell on Earth or Bloodline can claim.

And even though its Hellraiser elements feel underused and badly misconceived, Hellraiser; Inferno is still able to find its way into the disturbing fleshiness that is the central feature of its (possibly adopted) franchise. The twin women of Joe's visions are excellent additions to the community of Cenobites, designed with some delirious nightmare touches (the first time we see one, she appears to be a detached head rising up on spindly little spider-legs, given all of the various spikes poking out of various leather). Their worked into the film with sufficient uncanny power that even the long lizard tongues that should have been an immediate dealbreaker work to create an appropriately weird and warped feeling.

As for our returning villain Pinhead, I have to give Inferno this much credit: he's no longer a slasher movie monster. Part of what made Hellraiser and Hellbound: Hellraiser II so distinct and nervy is that Pinhead and the other Cenobites aren't expressly murderous bad guys in those films. They're amoral third-party observers who have certain rules and philosophies that make extremely messy death a significant and perhaps inevitable side effect of their presence, but they don't kill for the love of killing. The latter two theatrical sequels fucked that up, to their considerable detriment. Hellraiser: Inferno doesn't get us back to the first pair of movies - its conception of Pinhead, as I've said, is placed into an explicitly Christian moral framework, and he doesn't work there any more than he worked in a weird Aliens riff back in 1996. But at least he's chilly, not psychopathic. That's a good shift back towards something that Bradley can work with, and even in his teeny amount of screentime, he manages to restore some of the taciturn dignity to the character, remaining towering and stern and more officious in his cruelty than bloodthirsty. It's not a lot - it is, in fact, very little - but it's enough to give one hope that the direct-to-video Hellraisers might not be all bad. Though it doesn't come a too much of a surprise that a crummy '00s horror movie is still a good deal better than a crummy '90s horror movie.

Body Count: Given the way the narrative is structured, with Joe walking into places where someone has already died and we don't always get a good look at the corpse, this is a meaningless stat, honestly. If we mean that a character is seen alive, and then is seen being killed on-screen, then there are 3, two of whom are the same character and one of whom we already saw dead earlier. That kind of thing. I'm tempted to cheat, and say that it's very much the driving force of the story that 10 people end up dead, and in some capacity we see or hear how all 10 of them die, so let's just go with that.

Reviews in this series

Hellraiser (Barker, 1987)

Hellbound: Hellraiser II (Randel, 1988)

Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth (Hickox, 1992)

Hellraiser: Bloodline (Smithee [Yagher], 1996)

Hellraiser: Inferno (Derrickson, 2000)

Hellraiser: Hellseeker (Bota, 2002)

Hellraiser: Deader (Bota, 2005)

Hellraiser: Hellworld (Bota, 2005)

Hellraiser: Revelations (García, 2011)

Hellraiser: Judgment (Tunnicliffe, 2018)

Hellraiser (Bruckner, 2022)

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

If you enjoyed this article, why not support Alternate Ending as a recurring donor through Patreon, or with a one-time donation via Paypal? For just a dollar a month you can contribute to the ongoing health of the site, while also enjoying several fun perks!

That being said, even if we accept the best-case version of the film's writing history - that it was born and bred to be the fifth Hellraiser movie and never anything but - we're still stuck with "so it was purpose-built to go in this franchise, and it's this fucking bad at it?" Maybe it's even more comforting to assume it was a patch-up job. Hellraiser: Inferno may or may not be a good standalone horror movie - I am inclined more towards "or may not" - but it's a broken-down catastrophe as a Hellraiser picture, flushing every of the weird and kinky and troubling philosophy underpinning even the very worst of the theatrically-released films that preceded it. Pinhead has up till now been both a morally unfathomable emblem of the desire for extreme sensory input at all cost, and an angry slashy-movie psychopath, and those are already two very different things to square; Inferno wants him to be "spiritual judge in an all but explicitly Christian moral universe", and I mean 90% of the point of these is that they are very obviously not Christian. Derrickson, however, is Christian, or at least he plays one at the movies (subsequent to this film, during his largely undeserved ongoing career in big studio features, he's directed two explicitly Christian horror films, 2005's The Exorcism of Emily Rose and 2014's Deliver Us from Evil), which isn't a problem as such, except that he seems to have gotten hung up on an extremely literal meaning of "hell" that's not compatible with the one the series had used up till this point, and much less interesting and complicated as well.

Even so, Inferno is better than Bloodline, and it is way the hell better than the 1992 Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth, because complain as much as I like, the Hellraisers were more than able to fuck up the basics long before they went direct to video. Derrickson isn't a director I care for very much, but it's still readily apparent that he had more than it took to make cheapie sludge like this. One could go so far as to accuse him of overdirecting the movie, I would even say, which is a pretty small and inconsequential insult as far as direct-to-video horror goes. Most of these sorts of movies barely feel directed at all; there might be points where Derrickson's unfocused "look at me! look what I can do!" showmanship gets tiresome, but it's got an aesthetic personality and something not unlike a decent budget to carry it off (I mean, the film was still cheap, at a reported $2 million, but not by DTV standards).

And I don't want to undersell that it is tiresome, in places. There's an early moment where our lead antihero, corrupt cop Joseph Thorne (Craig Sheffer, who had previously been involved with films based on author Clive Barker's writings when he starred in 1990's Nightbreed) comes home to his longsuffering wife (Noelle Evans) and daughter (Lindsay Taylor) - this is the kind of film that doesn't even briefly suppose that the antihero cop's wife needs any descriptive adjectives other than "longsuffering" - and registers a moment of tenderness towards the child by setting his cheek against her sleeping face. And for this shot, the camera rotates ninety degrees to lie on its side, so that Joe's head is pointing down and the daughter's head is pointing up, and the bed makes the right side of the frame. It's extremely fussy and while, in light of where the film ends up going, you can stretch so hard to come up with a dubious meaning about how he's facing down to hell and she's looking up towards heaven, or something equally symbolic, but it's mostly just a strange stylistic gesture that calls a hell of a lot attention to itself for no good reason.

At least the other directorial overreaching is generally in service of making this more X-treme or intense or whatnot. The one that leaps to mind, which also comes early on, is when Joe has gone to his favorite prostitute (and now we start to see why he is an antihero, and why his wife is longsuffering), and she drops slowly down out of the frame to give him a blow job, a standard enough shot, at which the frame fades to red. Then it fades back in to a sex scene that has been so overexposed that he basically only see vague patches of shadow representing the human face in the field of bleached-out white. Again, it doesn't really do much, but at least creates a kind of heightened... something. "This movie fucks, and it's ugly, because humanity is ugly!" That kind of thing. I guess.

Other little random spurts of high style come and go - there's a dingy rural-looking bar with neon lights hanging on its outside walls that could not possibly flag its complete debt to Twin Peaks any harder, for example, and it's apparent (though less shameless) in a few other places that Derrickson knows his David Lynch - but for the most part, Hellraiser: Inferno quickly settles into a very clear stylistic groove, and that groove's name is "violent crime horror released in the wake of Se7en". It might even be more specifically "in the wake of the post-Se7en television crime series Millennium", given the particularly occult and torture-centric vision of human depravity that Inferno builds its mystery around: Joe has been put case of ritualistic serial murders where the bodies have been subject to some kind of horrible torment and mortification, and every crime scene includes a finger that has been chopped off of a human child's hand.

At the first of these, he also finds a small filigreed box, our good friend the Lament Configuration - which is given that name in dialogue, making it I believe the first Hellraiser movie to make that name text - and of course he immediately starts poking at it and causes it to open. Immediately following this, Joe starts to have strange visions of horrific violence that later turns out to come to pass, as well as seeing two women (Lynn Speier, Trisha Kara) who have been identically mutilated in elaborate, ritualistic-looking ways. Soon enough, Joe has connected the murders to a shadowy figure know as The Engineer (a name from barker's novella The Hellbound Heart, from which this franchise ultimately derives; it meant something very different there), and at the same time, the Engineer's MO changes, so that by chance or design, he's only killing people Joe personally knows.

None of this has much of anything to do with Hellraiser, and it will have even less to do with Hellraiser as it enters its third act and we start to learn just what evil Joe actually unleashed when he solved that puzzle box, but I think we can err on the side of charity and overlook that. After all, if having anything to do with Hellraiser gets us Hell on Earth, we're well rid of it. Taken solely on its own terms as a psychology horror mystery about a dirty cop and all-around shitty person being forced to look at the cruelty of the world as a reflection of his own awful behavior, Inferno isn't terrible. It's got some pretty significant problems, of which the most persistent is Sheffer's performance: he's being hammy and over the top in his performance of a gruff "mean asshole", lowering his eyes to glower all the time and clenching his teeth so hard it's a wonder they don't shatter, and keeping his mouth locked into big frown, almost more like a pouty child than anything else.

It's a pretty flimsy, unconvincing lead performance, and it has a major negative effect on a film whose overall strategy is entirely based on the filmmakers' ability to create a convincing mood of brutal moral decay; it's a severe and serious movie with a goofy mock-serious dead weight in its center, around whom virtually everything else in the entire movie pivots. But let us give Inferno credit where it is due: Derrickson and his crew have done a fairly good job at recycling that "1990s nihilism chic" aesthetic, creating a movie whose heavy atmosphere might have been done better elsewhere, but it has a heavy atmosphere, and that's more than either Hell on Earth or Bloodline can claim.

And even though its Hellraiser elements feel underused and badly misconceived, Hellraiser; Inferno is still able to find its way into the disturbing fleshiness that is the central feature of its (possibly adopted) franchise. The twin women of Joe's visions are excellent additions to the community of Cenobites, designed with some delirious nightmare touches (the first time we see one, she appears to be a detached head rising up on spindly little spider-legs, given all of the various spikes poking out of various leather). Their worked into the film with sufficient uncanny power that even the long lizard tongues that should have been an immediate dealbreaker work to create an appropriately weird and warped feeling.

As for our returning villain Pinhead, I have to give Inferno this much credit: he's no longer a slasher movie monster. Part of what made Hellraiser and Hellbound: Hellraiser II so distinct and nervy is that Pinhead and the other Cenobites aren't expressly murderous bad guys in those films. They're amoral third-party observers who have certain rules and philosophies that make extremely messy death a significant and perhaps inevitable side effect of their presence, but they don't kill for the love of killing. The latter two theatrical sequels fucked that up, to their considerable detriment. Hellraiser: Inferno doesn't get us back to the first pair of movies - its conception of Pinhead, as I've said, is placed into an explicitly Christian moral framework, and he doesn't work there any more than he worked in a weird Aliens riff back in 1996. But at least he's chilly, not psychopathic. That's a good shift back towards something that Bradley can work with, and even in his teeny amount of screentime, he manages to restore some of the taciturn dignity to the character, remaining towering and stern and more officious in his cruelty than bloodthirsty. It's not a lot - it is, in fact, very little - but it's enough to give one hope that the direct-to-video Hellraisers might not be all bad. Though it doesn't come a too much of a surprise that a crummy '00s horror movie is still a good deal better than a crummy '90s horror movie.

Body Count: Given the way the narrative is structured, with Joe walking into places where someone has already died and we don't always get a good look at the corpse, this is a meaningless stat, honestly. If we mean that a character is seen alive, and then is seen being killed on-screen, then there are 3, two of whom are the same character and one of whom we already saw dead earlier. That kind of thing. I'm tempted to cheat, and say that it's very much the driving force of the story that 10 people end up dead, and in some capacity we see or hear how all 10 of them die, so let's just go with that.

Reviews in this series

Hellraiser (Barker, 1987)

Hellbound: Hellraiser II (Randel, 1988)

Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth (Hickox, 1992)

Hellraiser: Bloodline (Smithee [Yagher], 1996)

Hellraiser: Inferno (Derrickson, 2000)

Hellraiser: Hellseeker (Bota, 2002)

Hellraiser: Deader (Bota, 2005)

Hellraiser: Hellworld (Bota, 2005)

Hellraiser: Revelations (García, 2011)

Hellraiser: Judgment (Tunnicliffe, 2018)

Hellraiser (Bruckner, 2022)

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

If you enjoyed this article, why not support Alternate Ending as a recurring donor through Patreon, or with a one-time donation via Paypal? For just a dollar a month you can contribute to the ongoing health of the site, while also enjoying several fun perks!

Categories: crime pictures, horror, mysteries, needless sequels, summer of blood