Summer of Blood: All gone to Hell

It was undoubtedly too much to hope that a horror movie as idiosyncratic as Hellraiser would end up producing one good sequel after another, especially given its perch at the end of the 1980s. In fact, it was already too much to hope that Hellraiser would have been able to produce even one good sequel, which is why Hellbound: Hellraiser II is such a delightful surprise. And I won't lie, even though I knew better, part of me was sufficiently bold to think, softly and to myself, "Heck, if they could get it right once..."

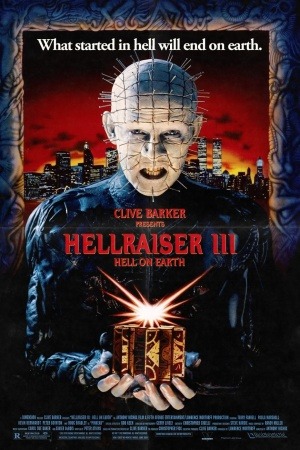

No, no, no, younger and more innocent version of me. Getting it right once means not a damn thing, and sure enough, Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth sucks. Like, a lot. And that's disappointing, but not at all shocking - after all, Hell on Earth didn't make itself known until 1992, four whole years after the second film, and if the late '80s were a rough and uncertain time for horror movies, the early '90s (by which I suppose I mean 1989 through 1995) might very well be the worst stretch of horror cinema since the genre was born in the silent era. Add that time frame to the long gap in between entries (never a good sign in horror franchises, though it must have been nice for that four years when there were only good Hellraiser movies), and the elementary fact that horror sequels are already a dodgy prospect, and, well... I will not say, "it's surprising Hell on Earth is as good as it managed to be", because that would be horribly misleading. "As good as it managed to be", in this case, is pretty fucking bad. But it is, anyway, gratifying that Hell on Earth didn't find a way to be much, much worse.

Oh my, where to begin? With the beginning, I suppose, where we meet a man it's pretty much impossible not to detest immediately. He is, though we don't know this yet, J.P. Monroe (Kevin Bernhardt), the smug owner of a popular nightclub in whatever indeterminate city the film takes place, and he's looking for decoration in a tiny little art gallery that keeps peculiar hours to suit its shady business model. Or at least this is the obvious presumption to make, given that J.P. shows up there in the middle of the night, and that the particular objet d'art that catches his eye is the very same pillar in which the souls of the four Cenobites were trapped at the end of Hellbound, along with the puzzle box that lets them out into the world - the Pillar of Souls, I take it to be called, in Hellraiser circles, but I don't believe that name ever appears in the movie, and so I will call it the Hellpillar, like I was doing in my head the whole time I was watching.

With this little taste of things to come, we switch over to find Joey (Terry Farrell), a resentful TV news reporter who has just finally managed to convince her bosses that she deserves a big break, only to find that her "big break" involves being given a shitty assignment about which there is nothing interesting to say, at the local hospital. You can tell she's the protagonist because she has an androgynous name; and it was at this exact moment that I stopped wondering if Hell on Earth was going to be better than I'd heard, because any 1992 film that couldn't be bothered to avoid even the laziest '80s horror tropes is not a 1992 film that is going to be very much fun to watch. At any rate, Joey and her cameraman Doc (Ken Carpenter) are just about to pack it up when an emergency case comes in: it's a young man covered in the spiny chains that we certainly ought to recognise by this point in the series can only mean that Hell is breaking loose. Joey hasn't quite processed what's going on around her when the man is ripped apart, but she does note two things he says: "Boiler Room" and "Terri".

At this point, her reporter sense kicks in, and she tracks the dead man back to The Boiler Room, that very same nightclub that J.P. runs. We now get to find out that J.P. has become so successful by catering to literally every possible niche audience: The Boiler Room appears at first to be a BDSM-themed bar (complete with darling little decorations of baby dolls about to be pierced by spikes), but inside a little bit more, and it's just your average industrial rave club, and what's through this door here? Well, duh, it's an elegant full-service restaurant with white linen tablecloths and crystal place settings.

The Boiler Room makes no goddamn sense.

While she's poking about, Joey eventually finds a path of breadcrumbs* that lead her straight to Terri (Paula Marshall), who stole the puzzle box in the first place. Seems that she had a bit of a flirtation with J.P. that ended badly, and that is why she stole the only removable piece of the hideous new statue he just installed in his private bedchamber behind The Boiler Room. Taking pity on the young girl, Joey lets her stay the night, while continuing her hunt: eventually, she finds that the Hellpillar was bought from an estate sale at an old asylum, and it's connected somehow to a girl named Kirsty Cotton. From then, it's a simple matter to get hold of the tapes of Kirsty's interviews with the doctors, providing Ashley Laurence with a tremendously unnecessary cameo. More importantly, the tape is interrupted by a mysterious figure of a British WWI officer (Doug Bradley) who addresses Joey by name and gives her cryptic advice.

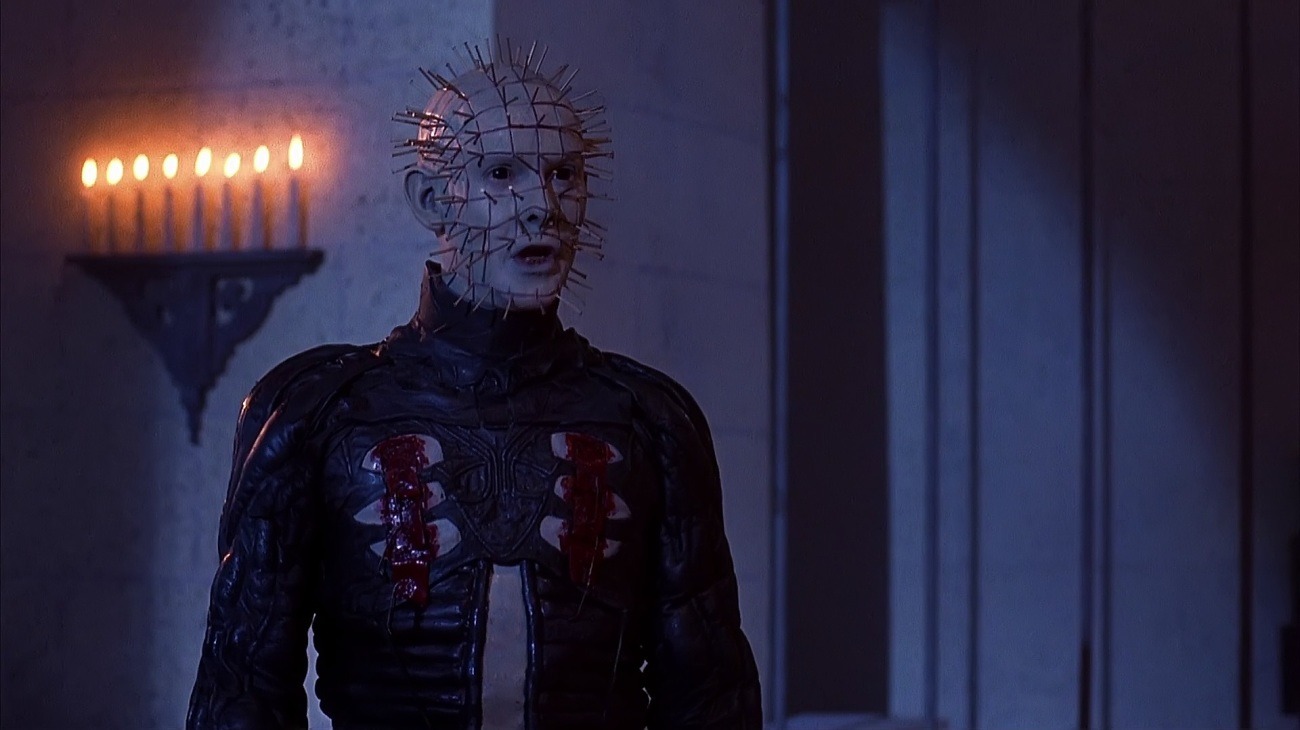

While all this has been happening, an errant spot of rat blood has ended up on the Hellpillar, and sure enough, it revives our beloved Pinhead (Doug Bradley, as well), though he doesn't make his full self known until after J.P. brings a random clubgoer back to his pad for a one-night stand that ends with her being devoured flesh-first by the statue. Pinhead quickly appeals to J.P.'s lesser nature, and they make a pact: J.P. will keep bringing bodies, and when Pinhead is able to escape his bonds and bring Hell itself to Earth, J.P. gets to stay alive. This backfires fairly spectacularly, for when he manages to cajole Terri into coming back for another go-round, J.P. ends up being eaten by the Hellpillar himself. And so is Pinhead able to manifest himself in the flesh, as it were.

The good news is that Joey is ready, sort of. She's been having terrible dreams involving that British officer, who turns out to be the ghost of Captain Elliot Spencer. Spencer is the man who found the puzzle box during his quest to find greater and more exotic physical sensations following the shell-shock of the war - this is, incidentally, the only point at which Hell on Earth taps into anything resembling the metaphysics of Clive Barker's original script and novella that got the whole franchise going - subsequently being turned into Pinhead through the box's dark powers, and he explains what is going on. I will not also explain what is going on, because it makes the entirety of the Hellraiser series worse to know the details.

And so it is that Pinhead destroys God knows how many people in The Boiler Room, turns a bunch of them into Cenobites, and tromps down a few city streets until he faces off with Joey. I'm told that the big draw of this movie during its original release was "Pinhead walks free on the Earth!" and if that's the case, it must have been powerfully disappointing to see that this consisted of a few dingy city streets late at night, and an idiotic battle between neo-Cenobites whose designs are so ridiculous I would just as soon not describe them, and cops, ending in a bit of flashy ending that presumably makes sense to someone. I am not he.

If you walked into this cold, I think it might be possible to find Hell on Earth a leaden, but not especially wretched example of early-'90s body horror. Not a good movie, by any stretch: director Anthony Hickox has no sense at all for visual flair or pacing, and the interiors have a hideously over-lit feeling. Not in the sense of being too bright, but in the sense that the lighting that's there feels like stage lighting, a little bit too present for its own good. And the acting is pretty damn bad: Terry Farrell, later of Star Trek: Deep Space Nine is mediocre to fair in a role that only really asks her to be flinty, but that's enough to make her the best member of the main cast: Bernhardt is a clown, and Marshall's flailing and reedy line deliveries are indescribable (Bradley, of course, does as he does: but he's out to sea with some of the dialogue given to him). The make-up is effective, if sort of idiotic; the CD Cenobite in particular is something that should have remained on the drawing board.

As the third Hellraiser, though, Hell on Earth is beyond worthless. Once again, the whole concept behind the franchise has been rejiggered: first the Cenobites were masochistic sensualists beyond human kenning who lived in an alternate dimension, then they were former humans who had been turned into the guardians of what may have been the actual afterlife, and now... there's some in-movie dialogue explaining it, but in a nutshell, Pinhead is just a horror movie villain. He does evil because it delights him to do evil, and whatever the hell place he comes from, and what the box has to do with it, is left unexplained.

But no, despite how carefully screenwriter Peter Atkins makes certain to include the word "flesh" in the dialogue, there is no trace of the disturbing intersection between the physical and psychological that were the backbone of the first two films, and even though Bradley plays Pinhead in all the same ways, the villain feels much different, and more hollow: he's just a killer with outré fashion sense. He isn't actually dangerous, any more than any given movie psycho slasher is dangerous, because he just fills a story role. The old Pinhead represented a coherent and suitably disturbing philosophy, and was an infinitely better villain as a result.

Again, I do not hold this against the movie. Hellbound was already supposed to have committed all of these exact same sins, and we should count ourselves lucky that it ended up turning out so well. Hell on Earth simple fulfilled its duty as a delayed horror sequel, to suck all the air out that made the first movie good, and count on a brand name and an iconic killer to do the work of crafting a world or holding a point of view. The only real surprise with this is that Clive Barker was still onboard as an executive producer; one would have thought that he'd be a little more careful about what was happening to his baby, but in the end, money is money. And that is the only reason why Hell on Earth was made in the first place.

Body Count: There are so many people killed in the destruction of the club that I can't imagine how to count them. So if we focus on the "featured" deaths, it's 12, plus scads, plus another handful in Joey's dreams.

Reviews in this series

Hellraiser (Barker, 1987)

Hellbound: Hellraiser II (Randel, 1988)

Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth (Hickox, 1992)

Hellraiser: Bloodline (Smithee [Yagher], 1996)

Hellraiser: Inferno (Derrickson, 2000)

Hellraiser: Hellseeker (Bota, 2002)

Hellraiser: Deader (Bota, 2005)

Hellraiser: Hellworld (Bota, 2005)

Hellraiser: Revelations (García, 2011)

Hellraiser: Judgment (Tunnicliffe, 2018)

Hellraiser (Bruckner, 2022)

*Metaphorical ones.

No, no, no, younger and more innocent version of me. Getting it right once means not a damn thing, and sure enough, Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth sucks. Like, a lot. And that's disappointing, but not at all shocking - after all, Hell on Earth didn't make itself known until 1992, four whole years after the second film, and if the late '80s were a rough and uncertain time for horror movies, the early '90s (by which I suppose I mean 1989 through 1995) might very well be the worst stretch of horror cinema since the genre was born in the silent era. Add that time frame to the long gap in between entries (never a good sign in horror franchises, though it must have been nice for that four years when there were only good Hellraiser movies), and the elementary fact that horror sequels are already a dodgy prospect, and, well... I will not say, "it's surprising Hell on Earth is as good as it managed to be", because that would be horribly misleading. "As good as it managed to be", in this case, is pretty fucking bad. But it is, anyway, gratifying that Hell on Earth didn't find a way to be much, much worse.

Oh my, where to begin? With the beginning, I suppose, where we meet a man it's pretty much impossible not to detest immediately. He is, though we don't know this yet, J.P. Monroe (Kevin Bernhardt), the smug owner of a popular nightclub in whatever indeterminate city the film takes place, and he's looking for decoration in a tiny little art gallery that keeps peculiar hours to suit its shady business model. Or at least this is the obvious presumption to make, given that J.P. shows up there in the middle of the night, and that the particular objet d'art that catches his eye is the very same pillar in which the souls of the four Cenobites were trapped at the end of Hellbound, along with the puzzle box that lets them out into the world - the Pillar of Souls, I take it to be called, in Hellraiser circles, but I don't believe that name ever appears in the movie, and so I will call it the Hellpillar, like I was doing in my head the whole time I was watching.

With this little taste of things to come, we switch over to find Joey (Terry Farrell), a resentful TV news reporter who has just finally managed to convince her bosses that she deserves a big break, only to find that her "big break" involves being given a shitty assignment about which there is nothing interesting to say, at the local hospital. You can tell she's the protagonist because she has an androgynous name; and it was at this exact moment that I stopped wondering if Hell on Earth was going to be better than I'd heard, because any 1992 film that couldn't be bothered to avoid even the laziest '80s horror tropes is not a 1992 film that is going to be very much fun to watch. At any rate, Joey and her cameraman Doc (Ken Carpenter) are just about to pack it up when an emergency case comes in: it's a young man covered in the spiny chains that we certainly ought to recognise by this point in the series can only mean that Hell is breaking loose. Joey hasn't quite processed what's going on around her when the man is ripped apart, but she does note two things he says: "Boiler Room" and "Terri".

At this point, her reporter sense kicks in, and she tracks the dead man back to The Boiler Room, that very same nightclub that J.P. runs. We now get to find out that J.P. has become so successful by catering to literally every possible niche audience: The Boiler Room appears at first to be a BDSM-themed bar (complete with darling little decorations of baby dolls about to be pierced by spikes), but inside a little bit more, and it's just your average industrial rave club, and what's through this door here? Well, duh, it's an elegant full-service restaurant with white linen tablecloths and crystal place settings.

The Boiler Room makes no goddamn sense.

While she's poking about, Joey eventually finds a path of breadcrumbs* that lead her straight to Terri (Paula Marshall), who stole the puzzle box in the first place. Seems that she had a bit of a flirtation with J.P. that ended badly, and that is why she stole the only removable piece of the hideous new statue he just installed in his private bedchamber behind The Boiler Room. Taking pity on the young girl, Joey lets her stay the night, while continuing her hunt: eventually, she finds that the Hellpillar was bought from an estate sale at an old asylum, and it's connected somehow to a girl named Kirsty Cotton. From then, it's a simple matter to get hold of the tapes of Kirsty's interviews with the doctors, providing Ashley Laurence with a tremendously unnecessary cameo. More importantly, the tape is interrupted by a mysterious figure of a British WWI officer (Doug Bradley) who addresses Joey by name and gives her cryptic advice.

While all this has been happening, an errant spot of rat blood has ended up on the Hellpillar, and sure enough, it revives our beloved Pinhead (Doug Bradley, as well), though he doesn't make his full self known until after J.P. brings a random clubgoer back to his pad for a one-night stand that ends with her being devoured flesh-first by the statue. Pinhead quickly appeals to J.P.'s lesser nature, and they make a pact: J.P. will keep bringing bodies, and when Pinhead is able to escape his bonds and bring Hell itself to Earth, J.P. gets to stay alive. This backfires fairly spectacularly, for when he manages to cajole Terri into coming back for another go-round, J.P. ends up being eaten by the Hellpillar himself. And so is Pinhead able to manifest himself in the flesh, as it were.

The good news is that Joey is ready, sort of. She's been having terrible dreams involving that British officer, who turns out to be the ghost of Captain Elliot Spencer. Spencer is the man who found the puzzle box during his quest to find greater and more exotic physical sensations following the shell-shock of the war - this is, incidentally, the only point at which Hell on Earth taps into anything resembling the metaphysics of Clive Barker's original script and novella that got the whole franchise going - subsequently being turned into Pinhead through the box's dark powers, and he explains what is going on. I will not also explain what is going on, because it makes the entirety of the Hellraiser series worse to know the details.

And so it is that Pinhead destroys God knows how many people in The Boiler Room, turns a bunch of them into Cenobites, and tromps down a few city streets until he faces off with Joey. I'm told that the big draw of this movie during its original release was "Pinhead walks free on the Earth!" and if that's the case, it must have been powerfully disappointing to see that this consisted of a few dingy city streets late at night, and an idiotic battle between neo-Cenobites whose designs are so ridiculous I would just as soon not describe them, and cops, ending in a bit of flashy ending that presumably makes sense to someone. I am not he.

If you walked into this cold, I think it might be possible to find Hell on Earth a leaden, but not especially wretched example of early-'90s body horror. Not a good movie, by any stretch: director Anthony Hickox has no sense at all for visual flair or pacing, and the interiors have a hideously over-lit feeling. Not in the sense of being too bright, but in the sense that the lighting that's there feels like stage lighting, a little bit too present for its own good. And the acting is pretty damn bad: Terry Farrell, later of Star Trek: Deep Space Nine is mediocre to fair in a role that only really asks her to be flinty, but that's enough to make her the best member of the main cast: Bernhardt is a clown, and Marshall's flailing and reedy line deliveries are indescribable (Bradley, of course, does as he does: but he's out to sea with some of the dialogue given to him). The make-up is effective, if sort of idiotic; the CD Cenobite in particular is something that should have remained on the drawing board.

As the third Hellraiser, though, Hell on Earth is beyond worthless. Once again, the whole concept behind the franchise has been rejiggered: first the Cenobites were masochistic sensualists beyond human kenning who lived in an alternate dimension, then they were former humans who had been turned into the guardians of what may have been the actual afterlife, and now... there's some in-movie dialogue explaining it, but in a nutshell, Pinhead is just a horror movie villain. He does evil because it delights him to do evil, and whatever the hell place he comes from, and what the box has to do with it, is left unexplained.

But no, despite how carefully screenwriter Peter Atkins makes certain to include the word "flesh" in the dialogue, there is no trace of the disturbing intersection between the physical and psychological that were the backbone of the first two films, and even though Bradley plays Pinhead in all the same ways, the villain feels much different, and more hollow: he's just a killer with outré fashion sense. He isn't actually dangerous, any more than any given movie psycho slasher is dangerous, because he just fills a story role. The old Pinhead represented a coherent and suitably disturbing philosophy, and was an infinitely better villain as a result.

Again, I do not hold this against the movie. Hellbound was already supposed to have committed all of these exact same sins, and we should count ourselves lucky that it ended up turning out so well. Hell on Earth simple fulfilled its duty as a delayed horror sequel, to suck all the air out that made the first movie good, and count on a brand name and an iconic killer to do the work of crafting a world or holding a point of view. The only real surprise with this is that Clive Barker was still onboard as an executive producer; one would have thought that he'd be a little more careful about what was happening to his baby, but in the end, money is money. And that is the only reason why Hell on Earth was made in the first place.

Body Count: There are so many people killed in the destruction of the club that I can't imagine how to count them. So if we focus on the "featured" deaths, it's 12, plus scads, plus another handful in Joey's dreams.

Reviews in this series

Hellraiser (Barker, 1987)

Hellbound: Hellraiser II (Randel, 1988)

Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth (Hickox, 1992)

Hellraiser: Bloodline (Smithee [Yagher], 1996)

Hellraiser: Inferno (Derrickson, 2000)

Hellraiser: Hellseeker (Bota, 2002)

Hellraiser: Deader (Bota, 2005)

Hellraiser: Hellworld (Bota, 2005)

Hellraiser: Revelations (García, 2011)

Hellraiser: Judgment (Tunnicliffe, 2018)

Hellraiser (Bruckner, 2022)

*Metaphorical ones.