Blockbuster History: Germanic mythology

Every week this summer, we'll be taking an historical tour of the Hollywood blockbuster by examining an older film that is in some way a spiritual precursor to one of the weekend's wide releases. This week: at a sufficiently far remove, Thor: Love and Thunder is ultimately based on the legends and mythology of Northern European cultures of the first millennium AD. At much less of a remove, the same broadly defined folklore traditions have previously inspired a much different effects-driven spectacular, from a period when the didn't have "blockbuster-type" movies as such, though this enormous epic would certainly fit the bill if they did.

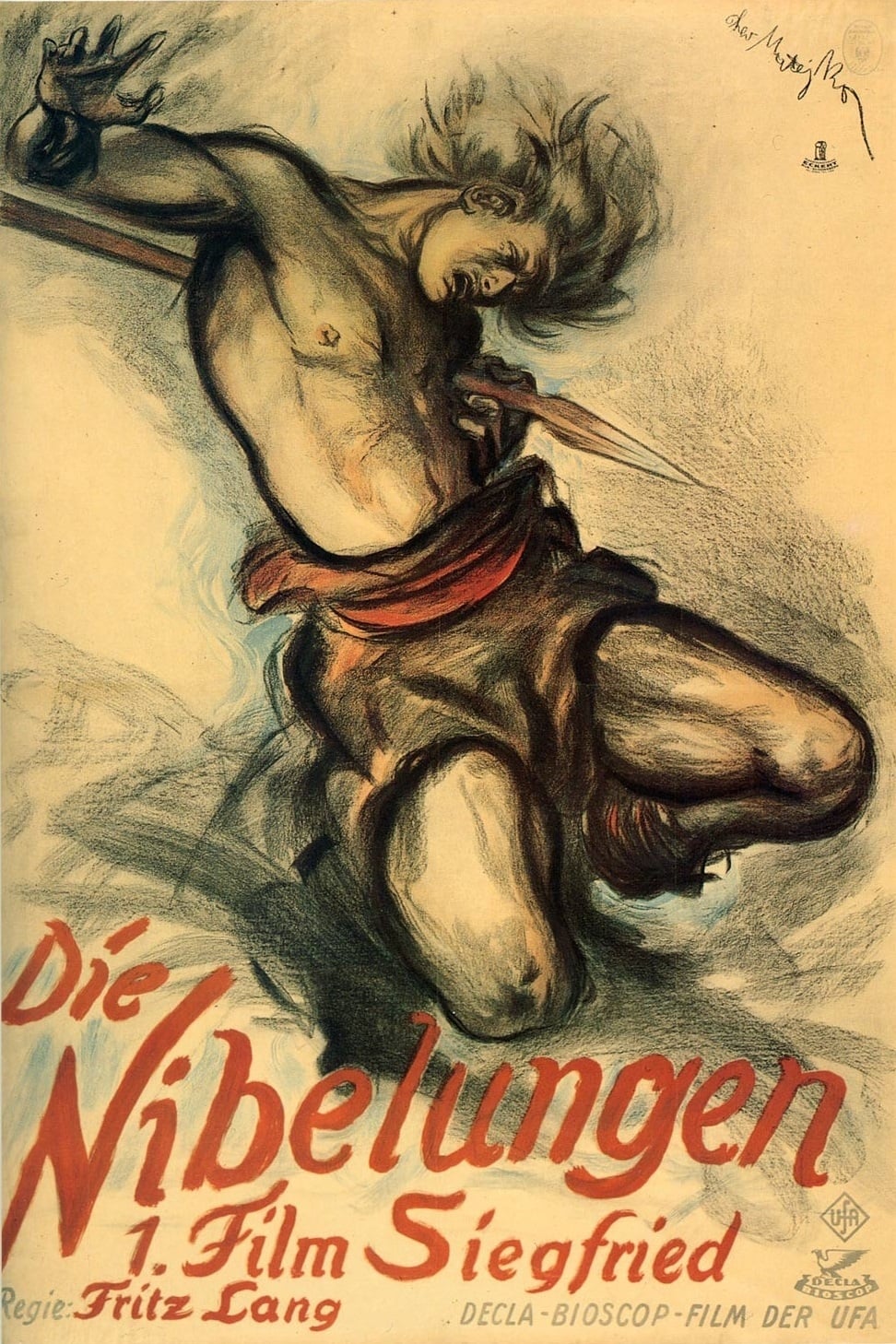

It's tough to have a handle on just how much there is to Die Nibelungen, a two-part epic film from 1924 directed by Fritz Lang from a script written by his then-wife Thea von Harbou. It was probably tough to have a handle on it in 1924, though at least audiences in the '20s were accustomed to a certain level of grandiose physical production. These were the glorious days of "oh, you need a full-scale sea battle between two armadas in your movie? Then I guess we had better stage a full-scale sea battle off the coast of Catalina", and what's especially cool about that is that you can't be certain what movie I'm referencing in that non-hypothetical, because it happened multiple times.* Almost a century later, our senses have been dulled by too much photorealistic CGI that allows filmmakers to create literally anything in the human imagination, as long as they don't mind that it's just the tiniest bit flat and weightless. Seeing a movie with the sheer damn scale of Lang's pair of films is like having rich curry after a long time only eating boiled oats.

Die Nibelungen is, to date, the most recent major artwork in a narrative tradition stretching back to around 1200 AD in a form we can directly document, though it was clearly old even then: the collection of stories accrued around a few generations of royal house of the Burgundians (sometimes called the Nibelungs), a Germanic tribe in the Rhine Valley who firmly entered recorded history in the early 5th Century. They were devastated by the Huns in 437 and relocated into what is now eastern France, where they were eventually absorbed, not without violence, into the Frankish Merovingian kingdoms, by the midpoint of the 6th Century. The story of their war with the Huns still echoed in the regions they had once lived, though, and over the centuries evolved into two similar but crucially distinct storytelling families. We might broadly define one of these as the "Norse" line, though by the time it reached written form in the 13th Century, it was largely centered in Iceland, which in that century produced both the prose Völsungasaga and a collection of poetry conventionally referred to as the Poetic Edda (the relative dating of the two, and their textual relationship, is a matter of conjecture). It was this material that substantially served as the basis for Richard Wagner's revision of the material into operatic form in the latter half of the 19th Century, the four-part cycle Der Ring des Nibelungen, which I would very comfortably declare the primary reason that the Nibelung lore remains well-known (insofar as it is well-known) all the way into the 21st Century.

The other line of descent, the "German" line, told a less fanciful and "mythic" version of the story, one more grounded in political history than misty archetypes (relatively speaking), and it probably produced a written version earlier, with the Middle High German epic poem Das Nibelungenlied ("The Song of the Nibelungs"), which is generally dated to around 1200. This is the version that Harbou and Lang adapted for their film, with considerable more fidelity than Wagner's free adaptation of Völsungasaga, and one must wonder if that was at least in part Lang's very deliberate way of saying "no, he did it all wrong, it should be this way". At a minimum, it's almost impossible to imagine Lang having a very high opinion of Wagner, an ill-tempered anti-Semite reactionary by the standards of the mid-19th Century, and far from being an attempt to ride on the opera's coattails, his diptych feels more like an attempt at a counternarrative, offering the German national epic in a form that's not quite so archly conservative and hung-up on racial purity (Lang would later flee Nazi Germany in 1933, almost as soon as there was such a thing as a "Nazi Germany" to flee from, while Harbou ended up as a prolific propagandist for the Third Reich. That's not the thing that specifically ended their marriage, but it must have led to some very fraught conversations). And even so, there are still some borrowings from Wagner's version of the story around the edges - its gravitational pull was just that strong.

Das Nibelungenlied, like many such antique texts whose origins are shrouded in uncertainty and competing documents, doesn't have a specific structure per se, though one has been conventionally placed upon it, and part of that convention is to observe that it cleaves pretty neatly into two halves. Lang and Harbou honored that cleavage in dividing their massive narrative (about four and three-quarter hours at the framerate used by the exquisite 2012 restoration conducted by Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung) right at the point where the plot undergoes a fairly massive shift. This leaves us with Die Nibelungen: Siegfried, released in the winter of '24, and Die Nibelungen: Kriemhild's Revenge, released in the spring, and now that I've spent all of this time setting the scene for you, it's time to take them each in turn. For they are, in fact, very distinct objects, focused on different narratives which are filmed using different stylistic approaches - they're even in different genres. Siegfried, our present subject, is the robust mythic fantasy of the pair, and it would be hard to deny that makes it considerably more fun to watch, whatever we might say about the films' relative quality. Or to put it another way, only one of the films has a dragon.

It's an extremely damn good dragon, too, and it comes quite early in the film; the encounter between Siegfried (Paul Richter) and the great beast makes up the plot of the first "canto", the division into roughly 25-minute chunks that the film takes to make itself more manageable still (and, one assumes, to accommodate the film projection technology available in the 1920s). Truthfully, the dragon sequence, as well as all of the first canto, does feel a bit detachable from the whole thing, which even with its fantastical touches is never again such an out-and-out fairy tale as it is here at the start. The situation we arrive to find is that Siegfried, a prince of the the kingdom of Xanten, has been studying how to forge a sword under the tutelage of the dwarflike creature Mime (Georg John), a great blacksmith. When we first see Siegfried, he has in fact just completed the finest sword Mime has ever seen, and feeling jealous, the smith sends his protégé on a "shortcut" through a dangerous, beast-infest wood. On the far side lies the castle of the Burgundians, where King Gunther (Theodor Loos) reigns alongside his two brothers and his sister Kriemhild (Margarete Schön), a legendary beauty. Upon hearing rumors of her in Mime's shop, Siegfried has decided to go straight to Burgundy and marry her.

But first, the dragon, and one of the most god-damnedest A+++ fantasy setpieces in all the many decades they've been making fantastic movies. First things first, it does not look like a "real" dragon in any useful sense. It looks like an enormous papier-mâché puppet, and it moves with an unmissable stiffness through a fairly limited number of articulated joints. That's not the exciting part. The exciting part is that this papier-mâché puppet is 60 feet long. It's practically a set unto itself, and seeing Richter stride up to it, in a shot scale that registers as medium-wide relative to the dragon but leaves Siegfried as a small little smudge in the frame, is as genuinely cowing and awe-inspiring as anything I've seen in any fantasy film from the near-century since Siegfried premiered. Even the obviously fake, clunky-looking dragon somehow adds to this effect rather than subtracts from it, because the palpable artifice of it acquires its own form of spectatorial appeal. We know that dragon puppet exists in the same physical space as Richter; even in 1924, visual effects trickery would have looked better than this. So we know that it's dozens of feet long. And we know that its movements are being caused by God knows how much human labor. The visibility of the filmmaking calls attention to how cool and ridiculously ambitious that filmmaking it is.

And that's without even mentioning how great the scene is as an example of staging - and Siegfried has, I genuinely think, some of the best staging in Lang's career and in the whole of the 1920s. The dragon is on a small bluff above a pond, with trees in the foreground; it's a fully three-dimensional space that's not just deep (from the trees to the dragon) and across (from the tree to Siegfried, also in the foreground), but up and down, as the pool below the dragon creates an additional axis of possible movement. These three axes are all given a full workout as Lang brings Richter up to the puppet, and then uses fast cutting of close-ups and medium shots to create a feeling of violent chaos in the fight between man and monster. These close-ups include detailed shot of Siegfried's sword piercing the dragon's eye, which pops out and uncorks a unrealistically strong stream of blood and ichor; I'm not going to call this the earliest gore effect I've ever seen or that exists, but it's a hell of a gross one, in a way that adds to the sense of physical reality and danger in the scene.

All told, it's a masterpiece-level scene, on par with anything else Lang ever directed, and it's hard not to feel like with its conclusion, Siegfried has peaked immodestly early. But for its remaining two hours, the film continues to be a superb and sumptuous example of all Lang's skills for arrange people in space as elements in a precisely-controlled geometric composition. And since Lang was one of the greatest directors in history for doing this exact thing, that's pretty superb indeed. The bulk of the story includes politicking at the Burgundian court of Worms, with Siegfried attempting to claim Kriemhild's hand from Gunther, but being told the price will be helping Gunther find and win the great warrior woman Brunhild (Hanna Ralph), Queen of Iceland. This happens, with the help of some magic artifacts Siegfried stole from the dwarf-hoard controlled by the Nibelung chieftain, Alberich (John again) - note that Lang and Harbou have here taken Wagner's use of "Nibelung" to refer to the dwarf race, rather than the Burgundians - and all is well, it seems. Siegfried and Kriemhild are ecstatically happy, and Brunhild is content (thanks to the subterfuge), that she has been taken as wife by the only man in the world who could best her in feats of strength, which is the only thing she wanted. But the more time she spends around the whinging, cowering Gunther, the more she figures out that something untoward is afoot. In fairly short order, she's begun manipulating the members of the court, notably Gunter's advisor Hagen Tronje (Hans Adalbert Schlettow), to figure out the truth and potentially set herself in a good position to avenge herself on the deceitful Gunther.

Part of the charm of Siegfried, which it borrows from Das Nibelungenlied, is that there are no real "good guys" here: just a bunch of people acting with short-sighted attention to their immediate best interests, and ending up making terribly compromised decisions as a result. Gunther is a selfish weakling, Siegfried is a jolly con artist, Brunhild is a devious plotter, Hagen is a treacherous lout. Kriemhild alone emerges as basically good all of the time, though she's not free of fits of jealous; her descent into amorality will eventually make up the bulk of Kriemhild's Revenge. The point being, the humans populating this story are, first and foremost, humans: they're complicated, admirable in some ways and unlikable in others, and not at all the declamatory stock types we might expect from a historical fantasy epic.

Siegfried's ability to capitalise on this nuanced human material isn't absolute, in part because the film's focus on iconography means that the actors are somewhat limited to striking bold poses and looking like painted figures. This is especially true of Richter, who gives the weakest of the lead performances, and in the main role; his Siegfried is truly nothing more than the sum of his manly chest and chiseled features. Other cast members are better to varying degrees; the women are the strongest performers here (and Schön will be better still in the next film), with Ralph finding ways of shading Brunhild as both righteous in her indignation and malicious in her decisions about how to avenger herself, based largely on her tight stances, wary and defensive, and the naked hatred in her facial expressions.

Still, this is a larger-than-life tale of bold historical currents embodied in singular humans, less about the singular humans themselves, and this is the mode where Lang and his collaborators thrive. It's not just that the well-framed and multidimensional images of the sets are gorgeous; the way those sets (designed by Otto Hunte and Karl Vollbrecht) wrap around the characters tends to add a layer of formal behavior that traps them in this world of courtly intrigue. Something similar happens with the costumes, designed by Paul Gerd Guderian and Aenne Willkomm; they look very little like the 13th Century and not a blessed thing like the 5th, but they're perfect anyway. The men's outfits are all dominated by geometric patterns, grides and lines that turn their bodies into pieces of the compositions, while Kriemhild's entire visual appearance, from her gown to the plaited braids framing her upper body, gives the impression that she's just a sculptural element. The images strongly give us the impression of characters who are locked into place in a world they can only survive, at best, and certainly not control or bend to their will. Lang's visual geometry, going forward, would always largely serve to explore how people are at the mercy of their environments, but I'm not sure that he ever bettered Siegfried for how much that geometry seems to be the founding principle of the entire culture the story depicts. This is a film of sternly rectilinear human spaces, dominated by doorways, daises, and enormous flights of perfectly symmetrical steps; and these are contrasted to the more naturally soft lines and organic shapes of the natural world of the Rhine (created mostly on soundstages), which is freer but more dangerous, a raw primeval wilderness that suggests, in all its unapologetic Romanticism, the messiness that the Burgundian court is forcibly trying to define itself against.

The one thing unifying all of it is the grandeur of it all; these are huge spaces for huge themes and a big story that had come to this movie with centuries of authority and dignity behind it. Humans get crushed in this aesthetic; they get crushed in this narrative, too, which is exactly the point. Siegfried is a story about deceit turning to ruin, humans who think they can control their destinies being snuffed out for their arrogant. It has a visual style that perfectly suits that, rendering the human spaces just as much as the natural ones places that are simply beyond human-sized concerns. It feels mythic and epic like very little else in all of cinema, including its own... sequel? Second half? Whatever the case, when we arrive at Kriemhild's Revenge, we'll find this grandeur has been redirected and the immaculate precision of the images given far less stress than it is here. But that's a different story with a different tragedy than this one; and for the specific tragedy contained within Siegfried, I genuinely cannot imagine how changing the aesthetic even slightly (up to and including Richter's theatrical posing) could do anything but lessen the impact of what I think might very well be a genuinely perfect work of the cinematic arts.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

If you enjoyed this article, why not support Alternate Ending as a recurring donor through Patreon, or with a one-time donation via Paypal? For just a dollar a month you can contribute to the ongoing health of the site, while also enjoying several fun perks!

*Not the Catalina part. That was me just randomly naming a place in California that has a coast.

It's tough to have a handle on just how much there is to Die Nibelungen, a two-part epic film from 1924 directed by Fritz Lang from a script written by his then-wife Thea von Harbou. It was probably tough to have a handle on it in 1924, though at least audiences in the '20s were accustomed to a certain level of grandiose physical production. These were the glorious days of "oh, you need a full-scale sea battle between two armadas in your movie? Then I guess we had better stage a full-scale sea battle off the coast of Catalina", and what's especially cool about that is that you can't be certain what movie I'm referencing in that non-hypothetical, because it happened multiple times.* Almost a century later, our senses have been dulled by too much photorealistic CGI that allows filmmakers to create literally anything in the human imagination, as long as they don't mind that it's just the tiniest bit flat and weightless. Seeing a movie with the sheer damn scale of Lang's pair of films is like having rich curry after a long time only eating boiled oats.

Die Nibelungen is, to date, the most recent major artwork in a narrative tradition stretching back to around 1200 AD in a form we can directly document, though it was clearly old even then: the collection of stories accrued around a few generations of royal house of the Burgundians (sometimes called the Nibelungs), a Germanic tribe in the Rhine Valley who firmly entered recorded history in the early 5th Century. They were devastated by the Huns in 437 and relocated into what is now eastern France, where they were eventually absorbed, not without violence, into the Frankish Merovingian kingdoms, by the midpoint of the 6th Century. The story of their war with the Huns still echoed in the regions they had once lived, though, and over the centuries evolved into two similar but crucially distinct storytelling families. We might broadly define one of these as the "Norse" line, though by the time it reached written form in the 13th Century, it was largely centered in Iceland, which in that century produced both the prose Völsungasaga and a collection of poetry conventionally referred to as the Poetic Edda (the relative dating of the two, and their textual relationship, is a matter of conjecture). It was this material that substantially served as the basis for Richard Wagner's revision of the material into operatic form in the latter half of the 19th Century, the four-part cycle Der Ring des Nibelungen, which I would very comfortably declare the primary reason that the Nibelung lore remains well-known (insofar as it is well-known) all the way into the 21st Century.

The other line of descent, the "German" line, told a less fanciful and "mythic" version of the story, one more grounded in political history than misty archetypes (relatively speaking), and it probably produced a written version earlier, with the Middle High German epic poem Das Nibelungenlied ("The Song of the Nibelungs"), which is generally dated to around 1200. This is the version that Harbou and Lang adapted for their film, with considerable more fidelity than Wagner's free adaptation of Völsungasaga, and one must wonder if that was at least in part Lang's very deliberate way of saying "no, he did it all wrong, it should be this way". At a minimum, it's almost impossible to imagine Lang having a very high opinion of Wagner, an ill-tempered anti-Semite reactionary by the standards of the mid-19th Century, and far from being an attempt to ride on the opera's coattails, his diptych feels more like an attempt at a counternarrative, offering the German national epic in a form that's not quite so archly conservative and hung-up on racial purity (Lang would later flee Nazi Germany in 1933, almost as soon as there was such a thing as a "Nazi Germany" to flee from, while Harbou ended up as a prolific propagandist for the Third Reich. That's not the thing that specifically ended their marriage, but it must have led to some very fraught conversations). And even so, there are still some borrowings from Wagner's version of the story around the edges - its gravitational pull was just that strong.

Das Nibelungenlied, like many such antique texts whose origins are shrouded in uncertainty and competing documents, doesn't have a specific structure per se, though one has been conventionally placed upon it, and part of that convention is to observe that it cleaves pretty neatly into two halves. Lang and Harbou honored that cleavage in dividing their massive narrative (about four and three-quarter hours at the framerate used by the exquisite 2012 restoration conducted by Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung) right at the point where the plot undergoes a fairly massive shift. This leaves us with Die Nibelungen: Siegfried, released in the winter of '24, and Die Nibelungen: Kriemhild's Revenge, released in the spring, and now that I've spent all of this time setting the scene for you, it's time to take them each in turn. For they are, in fact, very distinct objects, focused on different narratives which are filmed using different stylistic approaches - they're even in different genres. Siegfried, our present subject, is the robust mythic fantasy of the pair, and it would be hard to deny that makes it considerably more fun to watch, whatever we might say about the films' relative quality. Or to put it another way, only one of the films has a dragon.

It's an extremely damn good dragon, too, and it comes quite early in the film; the encounter between Siegfried (Paul Richter) and the great beast makes up the plot of the first "canto", the division into roughly 25-minute chunks that the film takes to make itself more manageable still (and, one assumes, to accommodate the film projection technology available in the 1920s). Truthfully, the dragon sequence, as well as all of the first canto, does feel a bit detachable from the whole thing, which even with its fantastical touches is never again such an out-and-out fairy tale as it is here at the start. The situation we arrive to find is that Siegfried, a prince of the the kingdom of Xanten, has been studying how to forge a sword under the tutelage of the dwarflike creature Mime (Georg John), a great blacksmith. When we first see Siegfried, he has in fact just completed the finest sword Mime has ever seen, and feeling jealous, the smith sends his protégé on a "shortcut" through a dangerous, beast-infest wood. On the far side lies the castle of the Burgundians, where King Gunther (Theodor Loos) reigns alongside his two brothers and his sister Kriemhild (Margarete Schön), a legendary beauty. Upon hearing rumors of her in Mime's shop, Siegfried has decided to go straight to Burgundy and marry her.

But first, the dragon, and one of the most god-damnedest A+++ fantasy setpieces in all the many decades they've been making fantastic movies. First things first, it does not look like a "real" dragon in any useful sense. It looks like an enormous papier-mâché puppet, and it moves with an unmissable stiffness through a fairly limited number of articulated joints. That's not the exciting part. The exciting part is that this papier-mâché puppet is 60 feet long. It's practically a set unto itself, and seeing Richter stride up to it, in a shot scale that registers as medium-wide relative to the dragon but leaves Siegfried as a small little smudge in the frame, is as genuinely cowing and awe-inspiring as anything I've seen in any fantasy film from the near-century since Siegfried premiered. Even the obviously fake, clunky-looking dragon somehow adds to this effect rather than subtracts from it, because the palpable artifice of it acquires its own form of spectatorial appeal. We know that dragon puppet exists in the same physical space as Richter; even in 1924, visual effects trickery would have looked better than this. So we know that it's dozens of feet long. And we know that its movements are being caused by God knows how much human labor. The visibility of the filmmaking calls attention to how cool and ridiculously ambitious that filmmaking it is.

And that's without even mentioning how great the scene is as an example of staging - and Siegfried has, I genuinely think, some of the best staging in Lang's career and in the whole of the 1920s. The dragon is on a small bluff above a pond, with trees in the foreground; it's a fully three-dimensional space that's not just deep (from the trees to the dragon) and across (from the tree to Siegfried, also in the foreground), but up and down, as the pool below the dragon creates an additional axis of possible movement. These three axes are all given a full workout as Lang brings Richter up to the puppet, and then uses fast cutting of close-ups and medium shots to create a feeling of violent chaos in the fight between man and monster. These close-ups include detailed shot of Siegfried's sword piercing the dragon's eye, which pops out and uncorks a unrealistically strong stream of blood and ichor; I'm not going to call this the earliest gore effect I've ever seen or that exists, but it's a hell of a gross one, in a way that adds to the sense of physical reality and danger in the scene.

All told, it's a masterpiece-level scene, on par with anything else Lang ever directed, and it's hard not to feel like with its conclusion, Siegfried has peaked immodestly early. But for its remaining two hours, the film continues to be a superb and sumptuous example of all Lang's skills for arrange people in space as elements in a precisely-controlled geometric composition. And since Lang was one of the greatest directors in history for doing this exact thing, that's pretty superb indeed. The bulk of the story includes politicking at the Burgundian court of Worms, with Siegfried attempting to claim Kriemhild's hand from Gunther, but being told the price will be helping Gunther find and win the great warrior woman Brunhild (Hanna Ralph), Queen of Iceland. This happens, with the help of some magic artifacts Siegfried stole from the dwarf-hoard controlled by the Nibelung chieftain, Alberich (John again) - note that Lang and Harbou have here taken Wagner's use of "Nibelung" to refer to the dwarf race, rather than the Burgundians - and all is well, it seems. Siegfried and Kriemhild are ecstatically happy, and Brunhild is content (thanks to the subterfuge), that she has been taken as wife by the only man in the world who could best her in feats of strength, which is the only thing she wanted. But the more time she spends around the whinging, cowering Gunther, the more she figures out that something untoward is afoot. In fairly short order, she's begun manipulating the members of the court, notably Gunter's advisor Hagen Tronje (Hans Adalbert Schlettow), to figure out the truth and potentially set herself in a good position to avenge herself on the deceitful Gunther.

Part of the charm of Siegfried, which it borrows from Das Nibelungenlied, is that there are no real "good guys" here: just a bunch of people acting with short-sighted attention to their immediate best interests, and ending up making terribly compromised decisions as a result. Gunther is a selfish weakling, Siegfried is a jolly con artist, Brunhild is a devious plotter, Hagen is a treacherous lout. Kriemhild alone emerges as basically good all of the time, though she's not free of fits of jealous; her descent into amorality will eventually make up the bulk of Kriemhild's Revenge. The point being, the humans populating this story are, first and foremost, humans: they're complicated, admirable in some ways and unlikable in others, and not at all the declamatory stock types we might expect from a historical fantasy epic.

Siegfried's ability to capitalise on this nuanced human material isn't absolute, in part because the film's focus on iconography means that the actors are somewhat limited to striking bold poses and looking like painted figures. This is especially true of Richter, who gives the weakest of the lead performances, and in the main role; his Siegfried is truly nothing more than the sum of his manly chest and chiseled features. Other cast members are better to varying degrees; the women are the strongest performers here (and Schön will be better still in the next film), with Ralph finding ways of shading Brunhild as both righteous in her indignation and malicious in her decisions about how to avenger herself, based largely on her tight stances, wary and defensive, and the naked hatred in her facial expressions.

Still, this is a larger-than-life tale of bold historical currents embodied in singular humans, less about the singular humans themselves, and this is the mode where Lang and his collaborators thrive. It's not just that the well-framed and multidimensional images of the sets are gorgeous; the way those sets (designed by Otto Hunte and Karl Vollbrecht) wrap around the characters tends to add a layer of formal behavior that traps them in this world of courtly intrigue. Something similar happens with the costumes, designed by Paul Gerd Guderian and Aenne Willkomm; they look very little like the 13th Century and not a blessed thing like the 5th, but they're perfect anyway. The men's outfits are all dominated by geometric patterns, grides and lines that turn their bodies into pieces of the compositions, while Kriemhild's entire visual appearance, from her gown to the plaited braids framing her upper body, gives the impression that she's just a sculptural element. The images strongly give us the impression of characters who are locked into place in a world they can only survive, at best, and certainly not control or bend to their will. Lang's visual geometry, going forward, would always largely serve to explore how people are at the mercy of their environments, but I'm not sure that he ever bettered Siegfried for how much that geometry seems to be the founding principle of the entire culture the story depicts. This is a film of sternly rectilinear human spaces, dominated by doorways, daises, and enormous flights of perfectly symmetrical steps; and these are contrasted to the more naturally soft lines and organic shapes of the natural world of the Rhine (created mostly on soundstages), which is freer but more dangerous, a raw primeval wilderness that suggests, in all its unapologetic Romanticism, the messiness that the Burgundian court is forcibly trying to define itself against.

The one thing unifying all of it is the grandeur of it all; these are huge spaces for huge themes and a big story that had come to this movie with centuries of authority and dignity behind it. Humans get crushed in this aesthetic; they get crushed in this narrative, too, which is exactly the point. Siegfried is a story about deceit turning to ruin, humans who think they can control their destinies being snuffed out for their arrogant. It has a visual style that perfectly suits that, rendering the human spaces just as much as the natural ones places that are simply beyond human-sized concerns. It feels mythic and epic like very little else in all of cinema, including its own... sequel? Second half? Whatever the case, when we arrive at Kriemhild's Revenge, we'll find this grandeur has been redirected and the immaculate precision of the images given far less stress than it is here. But that's a different story with a different tragedy than this one; and for the specific tragedy contained within Siegfried, I genuinely cannot imagine how changing the aesthetic even slightly (up to and including Richter's theatrical posing) could do anything but lessen the impact of what I think might very well be a genuinely perfect work of the cinematic arts.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

If you enjoyed this article, why not support Alternate Ending as a recurring donor through Patreon, or with a one-time donation via Paypal? For just a dollar a month you can contribute to the ongoing health of the site, while also enjoying several fun perks!

*Not the Catalina part. That was me just randomly naming a place in California that has a coast.