Foul deeds will rise

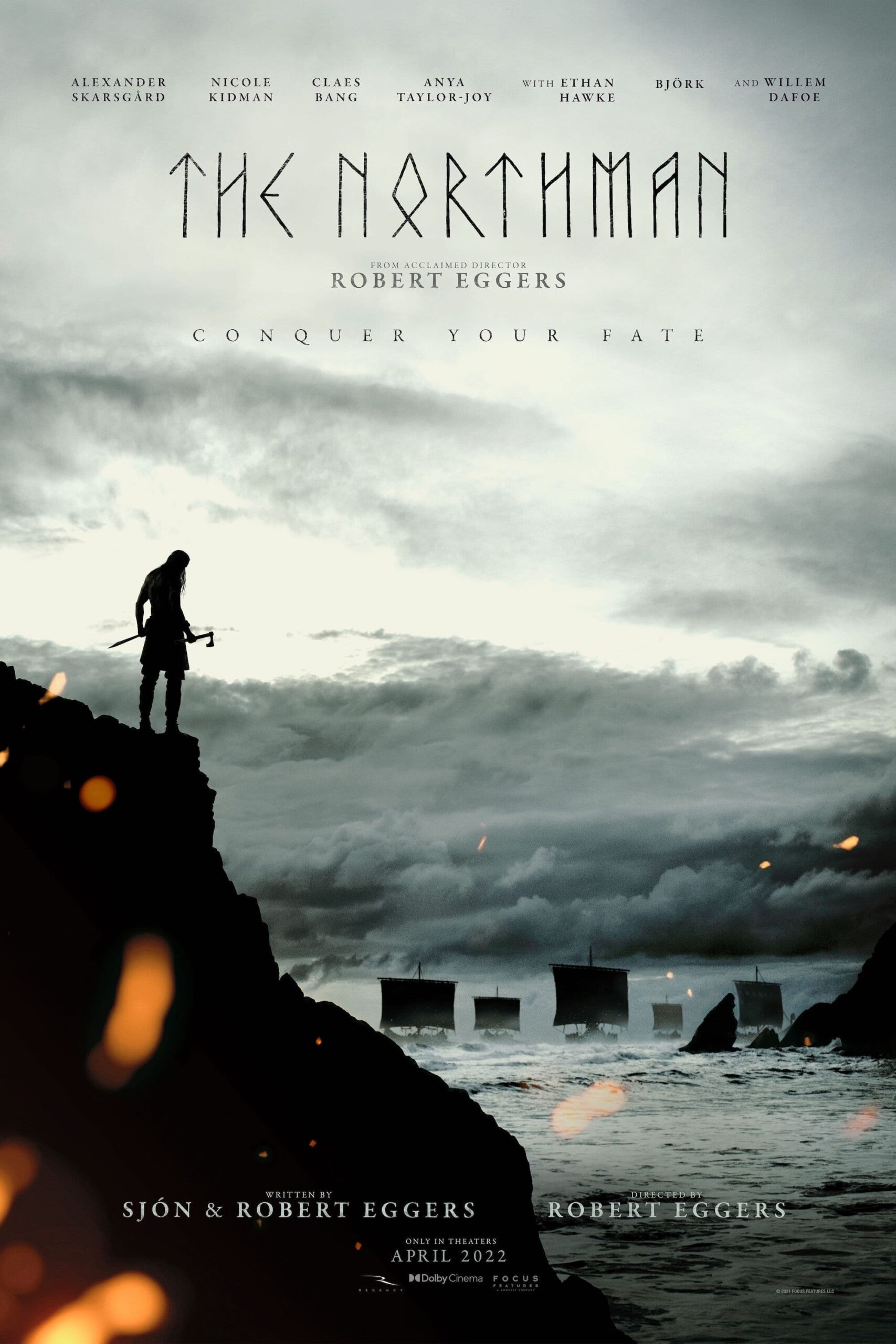

I'm always a sucker for films that tell us early on how we are to approach them, and The Northman - the third feature film directed by Robert Eggers after 2015's The Witch and 2019's The Lighthouse, and the one where I'm comfortable declaring in front of all the world that he's officially my favorite new American filmmaker of the last 10 years - is particularly obliging on that front. The very first thing that we see is a volcano belching lava, filling the frame; the very first thing we hear is a declaration from the god Óðinn, emerging from the heart of the volcano in a booming, electronically distorted voice that is uncredited, but I suspect is probably a composite of multiple of the film's male actors. It doesn't matter, or rather it almost matters that the film doesn't tell us who is doing the voice, because it contributes to the very important feeling the film is already working on creating: that we're listening to actual Óðinn (okay, fine, "Odin", I'll stop now), something deep and cosmic and primordial. And that's exactly what The Northman wants and needs us to think, because what the film is telling us right now, and will require us to know for every one of the film's 136 minutes thereafter, is that we're watching a film in which Odin exists in a real, tangible, non-fantastical way.

Or, at the very least, that this is a film made in the mindset of Odin existing. Very much like The Witch (to which it feels more like a direct follow-up than either feels of a piece with The Lighthouse), The Northman boasts as one of its best strengths that the filmmakers are telling a story built around a very different moral and philosophical, and even aesthetic worldview than our own. And this goes even farther, since The Witch is still ultimately grounded in Protestant Christianity, and presents a worldview that I imagine the vast majority of anglophone viewers would at least be able recognise as a variant form of one that still broadly speaking exists The Northman, in contrast, is set between 895 and around 915 CE, amongst the Norse people of northern Europe. Christianity is referenced briefly and viewed as a kind of impenetrable foreign religion that's off-putting but probably harmless. And that's the closest the film comes to intersecting with the mental landscape of currently-living people.

The film's narrative reflects a wholly alien way of inhabiting the world. It's a revenge story; it is, indeed, only a revenge story. It has carved down to the bone everything that does not fit into the précis, "a boy's father is brutally slaughtered, and he spends the rest of his life plotting how to brutally slaughter the man responsible". There are no grace notes or flourishes, just a steady line marching from Point A to Point B. The script, by Eggers and Icelandic poet Sjón, treats very seriously the idea of Fate as an active force in the daily lives of humans, a force as all-pervading and irresistible as gravity - or, in keeping with the film's brutal, raw setting, as irresistible as the deadly lash of ice cold seawater and the featureless faces of granite mountains. And it tells its story with that dedication to Fate locked in place. It is a film of unyielding straight lines - almost literal straight lines, visualised in the film's amazing tracking shots.

Not even tracking shots, really: push-ins. Eggers and cinematographer Jarin Blaschke have settled on an implacable compositional style that feels as ruthlessly beholden to right angles as anything this side of Wes Anderson, though used for almost precisely opposite reasons: no precious doll-house dioramas here, just merciless grids of movement through space and within frames. The push-ins are the best of these: throughout the movie, the camera relentless moves in perfect straight lines towards groups of characters, keeping them centered in compositions. It is somehow fluid and inorganic simultaneously, like water flowing down a rock face. Given that we know Eggers loves playing with the psychological impact of lettering (it is surely correct to claim that calling a film The VVitch sets us up for a very particular emotional and intellectual experience that just plain The Witch doesn't), I think it's only a little stretch to say that the push-ins put me in mind of a runic alphabet, like the one that gets used for all of the title cards in The Northman (they're then subtitled into English). Runes are, after all, a type of letting that fits the culture that used them: graceless, designed not for beauty but to survive the harsh condition of being etched violently into stone. Runes are cold and pragmatic and meant for living in rocky places that know mostly winter. And the push-ins have that same kind of feeling. There's nothing showy about them. They are blunt. They are carved into the world of the film, and they do not guide us so much as force us to look at things. Sometimes, a little bit of extra movement gets put into the shots, and this always magnifies that sense: for example, one early tracking shot begins to move at 45 degrees off the face of the lens towards the young prince, roughly transforming a group shot into a single that looks at him in his final moments of happy childhood innocence. Later, a shot moves onto a boat on a river, turning a stiff 90 degrees to look ahead, and then 90 degrees more to see the shore we've just moved from, as though moving anything other than a precise 90 degrees would shatter the inflexible POV of the primitive, barely-civilised setting.

And oh! how inflexible it is, and oh! how barely-civilised. The Northman is based on the legend of Amleth, which is certainly best-known to English speakers today as the ultimate source material for William Shakespeare's play Hamlet; this film and that play both have moved a decent way away from the legend, and not in the same direction. So all that remains is Amleth (Alexander Skarsgård), whose father King Aurvandill War-Raven (Ethan Hawke) was killed by his bastard half-uncle Fjölnir (Claes Bang), and whose mother Gudrún (Nicole Kidman) was taken as wife by the same bastard. In order to get close enough to Fjölnir to strike a fatal blow, Amleth pretends to be a dimwitted Rus slave, and having set up the pretense, he waits - in this case, for the signs given to him by Fate, not because of any internal psychological battle, like Shakespeare gave to his Hamlet. The Northman doesn't really afford its cast of characters any internal psychology. It wouldn't be in keeping with the brutally straightforward moral universe it is fleshing out, which consists of two kinds of people: the vicious, bestial thugs who we're rooting for, and the vicious, bestial thugs we're hoping to see die violently. And also Olga (Anya Taylor-Joy), an actual Rus slave that Amleth falls in love with, though just because she's not a bestial thug doesn't mean she really ends up with a character.

Given the extremely hard limits the film places on them, the cast does phenomenal work being expressive and striking big epic emotional states. The ones who are best are the ones who manage to feel the least like actual humans, ideally because they're playing figures who seem to emerge from the mists of dream and myth: literally, since the two best characters, with the two best performances backing them up, are Willem Dafoe as a mystic fool and Iceland's favorite singing elf-queen Björk (who has collaborated with Sjón as a lyricist) as a seeress who gives voice to that same Fate who feels like more of a real character than anyone else in the film. Björk solitary scene - it breaks my heart that she's not in more of the film, and the same time I think it's exactly the right choice - is the film's highlight, a phantasmagorical nightmare in which she seems to coalesce out of the grey murk that finds Blaschke seeming to experiment with the absolute least amount of light you need to expose 35mm film. We first see here as three serpentine eyes floating in a flat misty space, and slowly a mouth appears beneath those eyes, and they turn out to be shells or beads dangling from a headdress she's wearing, two of the shells hovering over the blacked-out holes where her actual eyes aren't. It's an image that feels at both brand new and impossibly ancient, and while I think the film's insistence on taking the superstitions and cosmology of the Norsemen at face value pays off pretty constantly throughout the film, it pays off the most here.

The other thing the film takes at face value is the ugly, guttural brutality of life on the shores of the North Sea, circa 1000 years ago. The project began from Skarsgård's desire to star in a proper Viking movie, and I have no idea if there's an ounce of historical accuracy here, but it sure does feel like this is digging into something terrible and powerful about the violence of that life. The film goes right on up to the edge of how much violence could be safely placed into a mainstream film, but it's not even really the violence per se that lingers, not even the striking, self-consciously iconic staging of that violence as battles between silhouettes in fog, in the deep blue night, against a raging volcano. It's the pageantry of violence. Far more than any of the film's beheadings, stabbings, dismemberments, or disembowelings (and those all do, in fact, need to be plurals), what chilled and terrified me was a scene of Amleth and several other Vikings, dressed in the animal hides of berserkers, dancing in a hideously perfect, even tuneful rhythm while a war poem was bellowed out. And as much as I have loved alliterative poetry ever since completely failing to read Beowulf in the original Old English at a young age, I don't think I realised till The Northman just how much intense, raging momentum could be packed into the distinctive, archaic patterns of that form. And the camera is doing its ruthless straight-line movement thing, while the actors describe chaotic but eerily precise circles. It's the film's best evocation of all the themes coursing through it: life as ritualised violence, pattern and repetition, men reducing themselves - or, more horrifyingly, elevating themselves to the status of ravenous wild animals.

It's all very bleak and cruel. And stylistically intoxicating: the film's fog and harsh landscapes and impenetrable night scenes all add up to images that combine raw ugliness and ethereal beauty in a striking unity. And I was quite swept away by Robin Carolan and Sebastian Gainsborough's musical score, pulsing out with a more refined, artful version of the same primitive instinct animating the rest of the film. But very bleak and cruel, and its defiantly anti-modern approach to storytelling is almost willfully off-putting: naturalistic character psychology doesn't even exist here as a rumor, and the story consists of one plot point iterated and repeated and inverted and refined over two hours in a way that borrows more from oral epic poetry than cinematic narration. But my God, it's a stunner, totally unlike anything else that gets released in theaters: it was an idiotic money sink and every penny that Focus Features won't get back is right on screen. Not that the last two years "count", but I haven't enjoyed a film this much since well before the pandemic got going in 2020, and I haven't been this eager to revisit the alien cadences of a bold new movie since... actually, since The Lighthouse, so there you have it.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

If you enjoyed this article, why not support Alternate Ending as a recurring donor through Patreon, or with a one-time donation via Paypal? For just a dollar a month you can contribute to the ongoing health of the site, while also enjoying several fun perks!

Or, at the very least, that this is a film made in the mindset of Odin existing. Very much like The Witch (to which it feels more like a direct follow-up than either feels of a piece with The Lighthouse), The Northman boasts as one of its best strengths that the filmmakers are telling a story built around a very different moral and philosophical, and even aesthetic worldview than our own. And this goes even farther, since The Witch is still ultimately grounded in Protestant Christianity, and presents a worldview that I imagine the vast majority of anglophone viewers would at least be able recognise as a variant form of one that still broadly speaking exists The Northman, in contrast, is set between 895 and around 915 CE, amongst the Norse people of northern Europe. Christianity is referenced briefly and viewed as a kind of impenetrable foreign religion that's off-putting but probably harmless. And that's the closest the film comes to intersecting with the mental landscape of currently-living people.

The film's narrative reflects a wholly alien way of inhabiting the world. It's a revenge story; it is, indeed, only a revenge story. It has carved down to the bone everything that does not fit into the précis, "a boy's father is brutally slaughtered, and he spends the rest of his life plotting how to brutally slaughter the man responsible". There are no grace notes or flourishes, just a steady line marching from Point A to Point B. The script, by Eggers and Icelandic poet Sjón, treats very seriously the idea of Fate as an active force in the daily lives of humans, a force as all-pervading and irresistible as gravity - or, in keeping with the film's brutal, raw setting, as irresistible as the deadly lash of ice cold seawater and the featureless faces of granite mountains. And it tells its story with that dedication to Fate locked in place. It is a film of unyielding straight lines - almost literal straight lines, visualised in the film's amazing tracking shots.

Not even tracking shots, really: push-ins. Eggers and cinematographer Jarin Blaschke have settled on an implacable compositional style that feels as ruthlessly beholden to right angles as anything this side of Wes Anderson, though used for almost precisely opposite reasons: no precious doll-house dioramas here, just merciless grids of movement through space and within frames. The push-ins are the best of these: throughout the movie, the camera relentless moves in perfect straight lines towards groups of characters, keeping them centered in compositions. It is somehow fluid and inorganic simultaneously, like water flowing down a rock face. Given that we know Eggers loves playing with the psychological impact of lettering (it is surely correct to claim that calling a film The VVitch sets us up for a very particular emotional and intellectual experience that just plain The Witch doesn't), I think it's only a little stretch to say that the push-ins put me in mind of a runic alphabet, like the one that gets used for all of the title cards in The Northman (they're then subtitled into English). Runes are, after all, a type of letting that fits the culture that used them: graceless, designed not for beauty but to survive the harsh condition of being etched violently into stone. Runes are cold and pragmatic and meant for living in rocky places that know mostly winter. And the push-ins have that same kind of feeling. There's nothing showy about them. They are blunt. They are carved into the world of the film, and they do not guide us so much as force us to look at things. Sometimes, a little bit of extra movement gets put into the shots, and this always magnifies that sense: for example, one early tracking shot begins to move at 45 degrees off the face of the lens towards the young prince, roughly transforming a group shot into a single that looks at him in his final moments of happy childhood innocence. Later, a shot moves onto a boat on a river, turning a stiff 90 degrees to look ahead, and then 90 degrees more to see the shore we've just moved from, as though moving anything other than a precise 90 degrees would shatter the inflexible POV of the primitive, barely-civilised setting.

And oh! how inflexible it is, and oh! how barely-civilised. The Northman is based on the legend of Amleth, which is certainly best-known to English speakers today as the ultimate source material for William Shakespeare's play Hamlet; this film and that play both have moved a decent way away from the legend, and not in the same direction. So all that remains is Amleth (Alexander Skarsgård), whose father King Aurvandill War-Raven (Ethan Hawke) was killed by his bastard half-uncle Fjölnir (Claes Bang), and whose mother Gudrún (Nicole Kidman) was taken as wife by the same bastard. In order to get close enough to Fjölnir to strike a fatal blow, Amleth pretends to be a dimwitted Rus slave, and having set up the pretense, he waits - in this case, for the signs given to him by Fate, not because of any internal psychological battle, like Shakespeare gave to his Hamlet. The Northman doesn't really afford its cast of characters any internal psychology. It wouldn't be in keeping with the brutally straightforward moral universe it is fleshing out, which consists of two kinds of people: the vicious, bestial thugs who we're rooting for, and the vicious, bestial thugs we're hoping to see die violently. And also Olga (Anya Taylor-Joy), an actual Rus slave that Amleth falls in love with, though just because she's not a bestial thug doesn't mean she really ends up with a character.

Given the extremely hard limits the film places on them, the cast does phenomenal work being expressive and striking big epic emotional states. The ones who are best are the ones who manage to feel the least like actual humans, ideally because they're playing figures who seem to emerge from the mists of dream and myth: literally, since the two best characters, with the two best performances backing them up, are Willem Dafoe as a mystic fool and Iceland's favorite singing elf-queen Björk (who has collaborated with Sjón as a lyricist) as a seeress who gives voice to that same Fate who feels like more of a real character than anyone else in the film. Björk solitary scene - it breaks my heart that she's not in more of the film, and the same time I think it's exactly the right choice - is the film's highlight, a phantasmagorical nightmare in which she seems to coalesce out of the grey murk that finds Blaschke seeming to experiment with the absolute least amount of light you need to expose 35mm film. We first see here as three serpentine eyes floating in a flat misty space, and slowly a mouth appears beneath those eyes, and they turn out to be shells or beads dangling from a headdress she's wearing, two of the shells hovering over the blacked-out holes where her actual eyes aren't. It's an image that feels at both brand new and impossibly ancient, and while I think the film's insistence on taking the superstitions and cosmology of the Norsemen at face value pays off pretty constantly throughout the film, it pays off the most here.

The other thing the film takes at face value is the ugly, guttural brutality of life on the shores of the North Sea, circa 1000 years ago. The project began from Skarsgård's desire to star in a proper Viking movie, and I have no idea if there's an ounce of historical accuracy here, but it sure does feel like this is digging into something terrible and powerful about the violence of that life. The film goes right on up to the edge of how much violence could be safely placed into a mainstream film, but it's not even really the violence per se that lingers, not even the striking, self-consciously iconic staging of that violence as battles between silhouettes in fog, in the deep blue night, against a raging volcano. It's the pageantry of violence. Far more than any of the film's beheadings, stabbings, dismemberments, or disembowelings (and those all do, in fact, need to be plurals), what chilled and terrified me was a scene of Amleth and several other Vikings, dressed in the animal hides of berserkers, dancing in a hideously perfect, even tuneful rhythm while a war poem was bellowed out. And as much as I have loved alliterative poetry ever since completely failing to read Beowulf in the original Old English at a young age, I don't think I realised till The Northman just how much intense, raging momentum could be packed into the distinctive, archaic patterns of that form. And the camera is doing its ruthless straight-line movement thing, while the actors describe chaotic but eerily precise circles. It's the film's best evocation of all the themes coursing through it: life as ritualised violence, pattern and repetition, men reducing themselves - or, more horrifyingly, elevating themselves to the status of ravenous wild animals.

It's all very bleak and cruel. And stylistically intoxicating: the film's fog and harsh landscapes and impenetrable night scenes all add up to images that combine raw ugliness and ethereal beauty in a striking unity. And I was quite swept away by Robin Carolan and Sebastian Gainsborough's musical score, pulsing out with a more refined, artful version of the same primitive instinct animating the rest of the film. But very bleak and cruel, and its defiantly anti-modern approach to storytelling is almost willfully off-putting: naturalistic character psychology doesn't even exist here as a rumor, and the story consists of one plot point iterated and repeated and inverted and refined over two hours in a way that borrows more from oral epic poetry than cinematic narration. But my God, it's a stunner, totally unlike anything else that gets released in theaters: it was an idiotic money sink and every penny that Focus Features won't get back is right on screen. Not that the last two years "count", but I haven't enjoyed a film this much since well before the pandemic got going in 2020, and I haven't been this eager to revisit the alien cadences of a bold new movie since... actually, since The Lighthouse, so there you have it.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

If you enjoyed this article, why not support Alternate Ending as a recurring donor through Patreon, or with a one-time donation via Paypal? For just a dollar a month you can contribute to the ongoing health of the site, while also enjoying several fun perks!

Categories: action, adventure, costume dramas, men with swords, shakespeare, top 10, violence and gore