Do not be frightened, it is only farce

A review requested by Kevin, with thanks to supporting Alternate Ending as a donor through Patreon.

Do you have a movie you'd like to see reviewed? This and other perks can be found on our Patreon page!

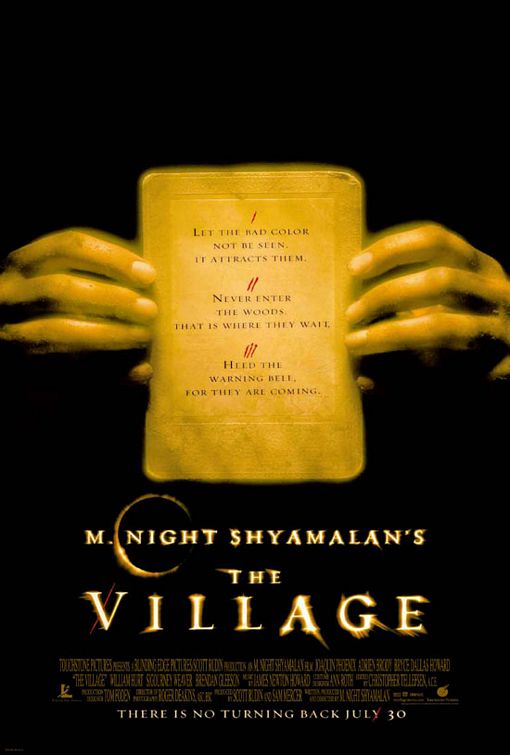

In later years, Film Twitter has (in its Film Twitter way) decided that M. Night Shyamalan's 2004 feature The Village is in fact better than its reputation. And since its reputation was that it was the specific moment that "promising but inconsistent young director M. Night Shyamalan" turned in the public's eye into "talentless idiot M. Night Shyamalan", it didn't take a lot to be better than that.

Big bold revisionist takes are fun and all, but I'm not able to join in this one. I will concede one point to the Shyamalan auteurists, though: saying the film is bad because of the pair of twists in the final act is largely unfair, and saying that the second of those twists, in particular is some combination of clichéd, predictable, arbitrary, or nonsensical isn't precisely the same thing as saying it's bad. I would certainly not say that it is good, but I think I can tolerate it at least as well as the reveals at the end of Signs, the director's preceding film, and that film certainly got a rosier critical reception than this one. But to the greater point, I agree that the twist ending doesn't ruin The Village; where I part ways with the film's younger generation of defenders is that the reason I think this is that I don't consider that there was anything to ruin. This was pretty whiffy a long way before the last act even starts. The Village has a script that magnifies all of Shyamalan's worst tics as a writer by requiring him to write arch, stylised dialogue, when he barely has ever demonstrated a convincing ability to write everyday human speech. It scatters a handful of trite character details across a large but ultimately under-developed cast, populated by a murderer's row of acting talent who have all been led to some very dubious places. I would indeed say that the twist comes closer to salvaging this than ruining it; it at least provides a possible explanation for why these people all feel so maddeningly inauthentic.

Anyway, I suspect that, all these years after its release, this has become one of those films better-known for how it ends than how it sents up that ending, so let's go back to the beginning. The village, Covington, is a small community surrounded on all sides by forest, and this has functionally locked it off from the rest of humanity. At least none of the younger generation - the village, broadly speaking, has just two, Elderly Parents and Twenty- and Thirty-Something Children (there are at least a few children of the thirtysomethings around and about, but we never really get to know any of them) - have ever apparently gone deep enough into the woods to lose sight of the scattering of buildings that make up their home. That's because those woods are home to Those We Don't Speak Of, a species of creature that is barely ever seen and understood even less, but some things are known. First and foremost, they are attracted by the color red, which they are also seen to wear, so absolutely nothing in the town can be that color. Second, they will kill you if you set foot into their territory, and they're also known to come into the village itself at night to cause terror, which is why the entire society of the villagers is built around maintaining watch fires and policing the boundary between forest and clearing, and only secondarily around doing the things that allow a small, isolated 19th Century community to continue existing.

This is the situation; the plot is a bit scrawnier than that. In a spectacular error of judgment, the film was marketed as a terrifying horror film about Those We Don't Speak Of, and it just isn't; Shyamalan was never really a "horror director", as much as that has always been his reputation (1999's The Sixth Sense was his only proper example of that genre all the way up to 2015's The Visit), and while there's one outright scene of terror in the film (which has been placed, narratively, after a point where the terror in question has been nullified, which is of the more obvious signs of how sloppy this script is), and quite a bit of lingering creepiness, this is trying to be something else entirely. Specifically, it's a moody fabulistic love story, and one that I think fails pretty hard, but that's for later in the review. The point is, the Touchstone Pictures marketing department leaned way the hell into the bloody otherworldly threat of Those We Speak Of Almost To The Exclusion Of Anything Else, and so raised expectations that The Village was absolutely not designed or equipped to pay off.

What it was designed to do is, again, kind of scrawny. Short version: Lucius Hunt (Joaquin Phoenix), the village's resident Quiet But Good Man, is quietly in love with Ivy Walker (Bryce Dallas Howard, in her first big role), the blind daughter of village elder Edward Walker (William Hurt). Lucius has ambitions to learn more about the world outside of the woods, earning him the distrust of every older resident of the town, including his own mother Alice (Sigourney Weaver); his actions seem to trigger a wave of Those activity as hasn't been seen in a while. This isn't really the story. At a certain point, Ivy and Lucius announce to the villagers their intent to wed, which upsets Noah Percy (Adrien Brody), the village's resident Blithering Idiot, who also has eyes for Ivy. So Noah stabs Lucius. This is the story, ultimately, but it takes a great deal of time to arrive.

Anyway, The Village is ultimately not really a "story" movie. Its title is already enough to tell us: this is about the society of the village, a somewhat Fordian assemblage of iconic types that can be pretty easily split into the camps of the younger folk who are just trying to live a better life, and the older folk who have a rather cumbersome and seemingly arbitrary collection of rules, act very furtive and mysterious, and are obviously hypocrites. Less because we have any specific evidence of hypocrisy, at first, than because the older generation, acting furtively in a somewhat Fordian story about a close-knit agrarian society, is always going to turn out to be hypocritical. Probably puritanical and reactionary as well, and wouldn't you know: they are.

All the more so since The Village isn't just a Fordian fable of a small community; it's also a full-fledged Post-9/11 movie. Edward Walker and the rest of the village elders aren't just run of the mill rural hypocrites; they're stand-ins for the authoritarian turn in the United States in the 2000s, when the fear of a barely-articulated Threatening Outsider and the all-encompassing desire to be safe and secure in little insular bubbles detached from the world as it's lived led to the rise of a censorious, and aye, puritanical government and culture in support of that government. It's all very serious and sincere, because of course, that has always really been Shyamalan's "thing": he is a nakedly sincere filmmaker of raw sentimentality, and there's an aching, lumpy earnestness at the heart of virtually every one of his movies other than The Visit and maybe 2016's Split. And I do not think it's a coincidence that those are, along with The Sixth Sense, his two best movies. For there are two problems here: one, Shyamalan's writing is too contrived and brittle and artificial to support real emotions, and he had never before written anything more brittle than The Village (a record that would be immediately broken by his next film, Lady in the Water). The cast here is full of top-notch talent: besides the names I have mentioned, Brendan Gleeson, Cherry Jones, and Celia Weston are all in the cast. And this killer ensemble is simply incapable of doing anything with the half-formed 19th Century clichés of their characters, and the not-even-half-formed lines they're spouting. Hurt's biggest speech finds him inserting pauses seemingly at random, like a phone call that keeps dropping out. The three main younger people, meanwhile, are all bad: Phoenix is boringly stolid in a role that offers nothing interesting to play, while Howard demonstrates the shallow lack of screen presence that would continue to crop up all the rest of her career. Brody's approach to playing an imbecile is a stunning, indescribably off-putting mixture of all the most tasteless, ugly, insulting shortcuts to playing intellectually disabled characters that have been developed by the hackiest actors throughout history. It's a simply unbearable performance, and it would probably be enough to make me dislike a much stronger film than The Village as it stands.

The other problem is that, like almost all of Shyamalan's films, this is all extremely stupid: the twist really is as nonsensical as the angriest critics said back in 2004, and while you can make it "work" - as in fact the film does, rather laboriously, much later in the proceedings than this amount of exposition is wanted or welcome - it's so contrived and unlikely, involving such batshit decisions by the people making them, that it can only function as a fable after that, not a real story about real people. And I do not think that the problem is the stupidity per se. It's that Shyamalan, again, is 100% sincere and unstinting in his desire to go for Big Emotions and to make Big Claims about The Problems of Today. He is very, very, very, very serious, and The Village, like many of his movies, is shlocky. Or, rather, it should be shlocky. Treat this with the crudeness of a '70s agrarian horror picture, and you've got something. Treat it as a solemn, prestigious middlebrow art film with popcorn movie trappings, and you have something airless and leaden, unable to get out of its own way, and pinioned by relying on the rich emotional connection between Ivy and Lucius that shows up nowhere whatsoever in Howard or Phoenix's performances.

The saving grace of all of this is that it's at least plush. Shyamalan's gifts as a visual creator can be and have been overstated, and I think he makes some blatant mistakes here: there is slow-motion used in a moment where it does incredible damage to the movie, and camera movement in general feels uncertain and randomly applied. But it is a pretty slinky-looking movie, as only something shot by the great Roger Deakins could look. The film's color conceit, in which there's no red and a whole shitload of yellow, is a weird limitation, but Deakins had long since proven himself an ace with monochromatic palettes, and he gives The Village a worn-out, autumnal feeling that makes everything feel cool and isolated even when there's nothing actively driving that feeling otherwise. And he has some fantastic torchlit sequences. The sets, designed by Tom Foden, and the costumes, designed by Ann Roth, work very nicely with that color palette to create a sense of the pre-industrial woods straight out of 19th Century painting; it's a little fanciful, a little nostalgic, and feeds into the storybook feeling of the last third that's pretty much the only place the film actually does something interesting tonally. James Newton Howard's score is an odd fit for the material, I think, but it has a lovely soaring quality that is considerably augmented by violin virtuoso Hilary Hahn, getting some terrific solos in. So no two ways about it: handsomely crafted. But there's no substance to how handsome it is; it feels like it's pretty in an effort to prop up the script rather than dress it out, or even just to be gorgeous-looking for the sake of beauty. And the script takes so much propping up; it is, in retrospect, nowhere close to Shyamalan's worst, but it's a damn site even from his somewhat contrived best.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

Do you have a movie you'd like to see reviewed? This and other perks can be found on our Patreon page!

In later years, Film Twitter has (in its Film Twitter way) decided that M. Night Shyamalan's 2004 feature The Village is in fact better than its reputation. And since its reputation was that it was the specific moment that "promising but inconsistent young director M. Night Shyamalan" turned in the public's eye into "talentless idiot M. Night Shyamalan", it didn't take a lot to be better than that.

Big bold revisionist takes are fun and all, but I'm not able to join in this one. I will concede one point to the Shyamalan auteurists, though: saying the film is bad because of the pair of twists in the final act is largely unfair, and saying that the second of those twists, in particular is some combination of clichéd, predictable, arbitrary, or nonsensical isn't precisely the same thing as saying it's bad. I would certainly not say that it is good, but I think I can tolerate it at least as well as the reveals at the end of Signs, the director's preceding film, and that film certainly got a rosier critical reception than this one. But to the greater point, I agree that the twist ending doesn't ruin The Village; where I part ways with the film's younger generation of defenders is that the reason I think this is that I don't consider that there was anything to ruin. This was pretty whiffy a long way before the last act even starts. The Village has a script that magnifies all of Shyamalan's worst tics as a writer by requiring him to write arch, stylised dialogue, when he barely has ever demonstrated a convincing ability to write everyday human speech. It scatters a handful of trite character details across a large but ultimately under-developed cast, populated by a murderer's row of acting talent who have all been led to some very dubious places. I would indeed say that the twist comes closer to salvaging this than ruining it; it at least provides a possible explanation for why these people all feel so maddeningly inauthentic.

Anyway, I suspect that, all these years after its release, this has become one of those films better-known for how it ends than how it sents up that ending, so let's go back to the beginning. The village, Covington, is a small community surrounded on all sides by forest, and this has functionally locked it off from the rest of humanity. At least none of the younger generation - the village, broadly speaking, has just two, Elderly Parents and Twenty- and Thirty-Something Children (there are at least a few children of the thirtysomethings around and about, but we never really get to know any of them) - have ever apparently gone deep enough into the woods to lose sight of the scattering of buildings that make up their home. That's because those woods are home to Those We Don't Speak Of, a species of creature that is barely ever seen and understood even less, but some things are known. First and foremost, they are attracted by the color red, which they are also seen to wear, so absolutely nothing in the town can be that color. Second, they will kill you if you set foot into their territory, and they're also known to come into the village itself at night to cause terror, which is why the entire society of the villagers is built around maintaining watch fires and policing the boundary between forest and clearing, and only secondarily around doing the things that allow a small, isolated 19th Century community to continue existing.

This is the situation; the plot is a bit scrawnier than that. In a spectacular error of judgment, the film was marketed as a terrifying horror film about Those We Don't Speak Of, and it just isn't; Shyamalan was never really a "horror director", as much as that has always been his reputation (1999's The Sixth Sense was his only proper example of that genre all the way up to 2015's The Visit), and while there's one outright scene of terror in the film (which has been placed, narratively, after a point where the terror in question has been nullified, which is of the more obvious signs of how sloppy this script is), and quite a bit of lingering creepiness, this is trying to be something else entirely. Specifically, it's a moody fabulistic love story, and one that I think fails pretty hard, but that's for later in the review. The point is, the Touchstone Pictures marketing department leaned way the hell into the bloody otherworldly threat of Those We Speak Of Almost To The Exclusion Of Anything Else, and so raised expectations that The Village was absolutely not designed or equipped to pay off.

What it was designed to do is, again, kind of scrawny. Short version: Lucius Hunt (Joaquin Phoenix), the village's resident Quiet But Good Man, is quietly in love with Ivy Walker (Bryce Dallas Howard, in her first big role), the blind daughter of village elder Edward Walker (William Hurt). Lucius has ambitions to learn more about the world outside of the woods, earning him the distrust of every older resident of the town, including his own mother Alice (Sigourney Weaver); his actions seem to trigger a wave of Those activity as hasn't been seen in a while. This isn't really the story. At a certain point, Ivy and Lucius announce to the villagers their intent to wed, which upsets Noah Percy (Adrien Brody), the village's resident Blithering Idiot, who also has eyes for Ivy. So Noah stabs Lucius. This is the story, ultimately, but it takes a great deal of time to arrive.

Anyway, The Village is ultimately not really a "story" movie. Its title is already enough to tell us: this is about the society of the village, a somewhat Fordian assemblage of iconic types that can be pretty easily split into the camps of the younger folk who are just trying to live a better life, and the older folk who have a rather cumbersome and seemingly arbitrary collection of rules, act very furtive and mysterious, and are obviously hypocrites. Less because we have any specific evidence of hypocrisy, at first, than because the older generation, acting furtively in a somewhat Fordian story about a close-knit agrarian society, is always going to turn out to be hypocritical. Probably puritanical and reactionary as well, and wouldn't you know: they are.

All the more so since The Village isn't just a Fordian fable of a small community; it's also a full-fledged Post-9/11 movie. Edward Walker and the rest of the village elders aren't just run of the mill rural hypocrites; they're stand-ins for the authoritarian turn in the United States in the 2000s, when the fear of a barely-articulated Threatening Outsider and the all-encompassing desire to be safe and secure in little insular bubbles detached from the world as it's lived led to the rise of a censorious, and aye, puritanical government and culture in support of that government. It's all very serious and sincere, because of course, that has always really been Shyamalan's "thing": he is a nakedly sincere filmmaker of raw sentimentality, and there's an aching, lumpy earnestness at the heart of virtually every one of his movies other than The Visit and maybe 2016's Split. And I do not think it's a coincidence that those are, along with The Sixth Sense, his two best movies. For there are two problems here: one, Shyamalan's writing is too contrived and brittle and artificial to support real emotions, and he had never before written anything more brittle than The Village (a record that would be immediately broken by his next film, Lady in the Water). The cast here is full of top-notch talent: besides the names I have mentioned, Brendan Gleeson, Cherry Jones, and Celia Weston are all in the cast. And this killer ensemble is simply incapable of doing anything with the half-formed 19th Century clichés of their characters, and the not-even-half-formed lines they're spouting. Hurt's biggest speech finds him inserting pauses seemingly at random, like a phone call that keeps dropping out. The three main younger people, meanwhile, are all bad: Phoenix is boringly stolid in a role that offers nothing interesting to play, while Howard demonstrates the shallow lack of screen presence that would continue to crop up all the rest of her career. Brody's approach to playing an imbecile is a stunning, indescribably off-putting mixture of all the most tasteless, ugly, insulting shortcuts to playing intellectually disabled characters that have been developed by the hackiest actors throughout history. It's a simply unbearable performance, and it would probably be enough to make me dislike a much stronger film than The Village as it stands.

The other problem is that, like almost all of Shyamalan's films, this is all extremely stupid: the twist really is as nonsensical as the angriest critics said back in 2004, and while you can make it "work" - as in fact the film does, rather laboriously, much later in the proceedings than this amount of exposition is wanted or welcome - it's so contrived and unlikely, involving such batshit decisions by the people making them, that it can only function as a fable after that, not a real story about real people. And I do not think that the problem is the stupidity per se. It's that Shyamalan, again, is 100% sincere and unstinting in his desire to go for Big Emotions and to make Big Claims about The Problems of Today. He is very, very, very, very serious, and The Village, like many of his movies, is shlocky. Or, rather, it should be shlocky. Treat this with the crudeness of a '70s agrarian horror picture, and you've got something. Treat it as a solemn, prestigious middlebrow art film with popcorn movie trappings, and you have something airless and leaden, unable to get out of its own way, and pinioned by relying on the rich emotional connection between Ivy and Lucius that shows up nowhere whatsoever in Howard or Phoenix's performances.

The saving grace of all of this is that it's at least plush. Shyamalan's gifts as a visual creator can be and have been overstated, and I think he makes some blatant mistakes here: there is slow-motion used in a moment where it does incredible damage to the movie, and camera movement in general feels uncertain and randomly applied. But it is a pretty slinky-looking movie, as only something shot by the great Roger Deakins could look. The film's color conceit, in which there's no red and a whole shitload of yellow, is a weird limitation, but Deakins had long since proven himself an ace with monochromatic palettes, and he gives The Village a worn-out, autumnal feeling that makes everything feel cool and isolated even when there's nothing actively driving that feeling otherwise. And he has some fantastic torchlit sequences. The sets, designed by Tom Foden, and the costumes, designed by Ann Roth, work very nicely with that color palette to create a sense of the pre-industrial woods straight out of 19th Century painting; it's a little fanciful, a little nostalgic, and feeds into the storybook feeling of the last third that's pretty much the only place the film actually does something interesting tonally. James Newton Howard's score is an odd fit for the material, I think, but it has a lovely soaring quality that is considerably augmented by violin virtuoso Hilary Hahn, getting some terrific solos in. So no two ways about it: handsomely crafted. But there's no substance to how handsome it is; it feels like it's pretty in an effort to prop up the script rather than dress it out, or even just to be gorgeous-looking for the sake of beauty. And the script takes so much propping up; it is, in retrospect, nowhere close to Shyamalan's worst, but it's a damn site even from his somewhat contrived best.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.