Where are you going?

A review requested by David, with thanks to supporting Alternate Ending as a donor through Patreon.

Do you have a movie you'd like to see reviewed? This and other perks can be found on our Patreon page!

Miike Takashi's whole "thing", as I suppose most people who know two things about him are aware (if they know only one thing, it's probably that he's ludicrously prolific, making like ten films every year for a couple of decades), is that he likes to do bizarre and unexpected things that pitch the audience right out of our comfort zone with the genres he's working in. As it generally does, this is mainly used to mean "he makes fucked-up, edgy, violent things", not least because in the anglosphere, his best-known film after almost a quarter of a century remains the freaked-out torture porn/romcom hybrid Audition, one of the early entries in the international trend towards extreme horror content in upsetting psychological thrillers that made up a great deal of horror cinema in the 2000s.

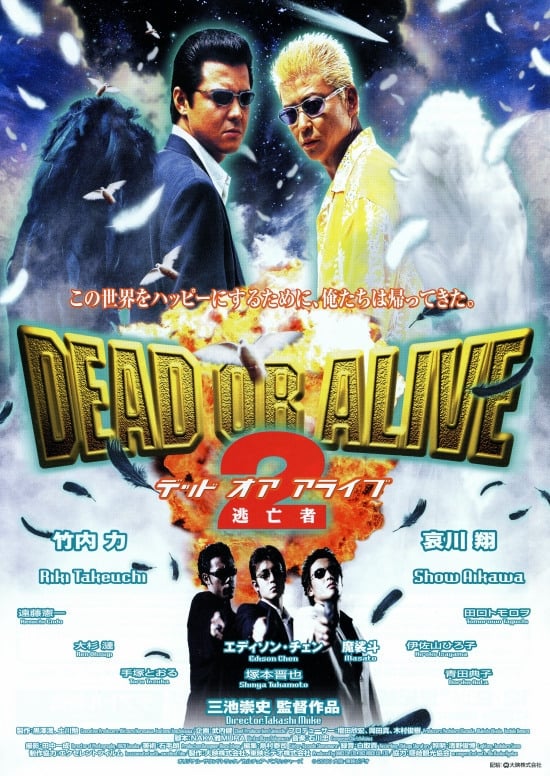

Miike's not really a "horror director" though - with a filmography that deep and wide, he's not really an anything director, but has tried out everything up to and including cheerful family films - and I think it is good to have an occasional reminder that transgressing boundaries in art does not necessarily mean filling it full of lurid adults-only content. At which point I'll clarify that our present subject is an adults-only proposition, but only somewhat incidentally, and that's not what's transgressive about it. The film in question is 2000's Dead or Alive 2: Birds, the middle entry in a trilogy-in-name-only of films connected only by Miike and lead actors Aikawa Shō and Takeuchi Riki (the first two are both yakuza films; the third doesn't even make this modest nod to unity), and on paper, it feels like just another one of the high-concept gangster pictures that became ubiquitous across the globe in the decade after Reservoir Dogs and Pulp Fiction introduced. Mizuki (Aikawa) is an assassin, hired to some yakuza or another in an ongoing gang war. Just as he's about to take his shot, though, some else gets to the target first. And as Mizuki digs into this a bit, he discovers that the other man who was hired to do the same job is also operating under the name of Mizuki.

So far, so much high-energy boilerplate: dueling hitman, hired to do the same job and presumably therefore in competition. And it doesn't really have to get any less boilerplate when Mizuki A discovers that Mizuki B is actually his childhood friend Shuuichi (Takeuchi); criminals being confronted with the shadowy echoes of their past is a longstanding pillar of the gangster genre. No, where DOA 2 becomes suddenly very weird and considerably unusual is in what happens to the film itself when Mizuki and Shuuichi cross paths on the ferry to the island where they lived as children: it transforms into a quiet, contemplative character drama about nostalgia and whether the children we were would be proud of the adults we are.

And so, back to my initial point: Miike's wisdom as a transgressive artist doesn't lie in his ability to pile more and more revolting, shocking, sardonically nihilistic material in to the stuff of a gangster picture. Gangster pictures had gotten extremely good at that by 2000 without having provocateurs like Miike doing that. Instead, the provocation of DOA 2 is to situate all of these gangland shenanigans in a warmly human narrative context, one with an unmistakable moral bent on top of everything. Though thankfully not one it feels the need to grandstand about. The film is, to a startling degree, not glib; is has in fact a kind of anti-glibness that's made all the more concrete and vivid because the film does make some highly ironic gestures. Perhaps the most overt of these comes near the the climax, when the film cross-cuts between a play staged for an audience of squealing children, and the violent deaths of several yakuza. And, just for added measure, the children's play is full of lewd sexual imagery (though I'm not entirely confident it would play as lewdly to a Japanese viewer as to this American). So that's an ironic, leering juxtaposition packed into a second ironic, leering juxtaposition.

The thing is, though, by the time we get to this point in DOA 2, the easy contrast between manic actors mugging for a bunch of happily shrieking children and spectacular, gaudy violence feels kind of pat and obvious - kind of, as I was saying, glib, and I think that Miike has not done this by accident. And he's definitely not doing it just to be smugly above-it-all; there's a lot of boisterous energy here, and the actors playing the actors are really going for it. But it's not just a "cool" gesture, something about it feels a little unsettled and ugly, and I feel like that's what we've been set up with by the earlier parts of the movie; to find something grim and morbid in the contrast, not sarcastic and snotty. And so, the anti-glibness: the real contrast isn't between death and children's entertainment, but between that kind of of slick filmmaking and the good-natured, sluggish sentimentality of the film's extremely long middle.

And with that, why don't we skip back to the middle? Dead or Alive 2: Birds is a crisp 97 minutes long, and it's astounding how many of those minutes simply put the narrative on pause to allow Mizuki and Shu to sink into their childhood memories as they reconnect on their island, find their old childhood friend Kohei (Endo Kenichi) and his pregnant wife Chieko (Aota Noriko), and visit the orphanage where they grew up. Much of this involves grainy flashbacks, and most of it involves cinematographer Tanaka Kazunari treating the film to give the whole thing a heavy yellow glow, the warm, fading tone of old photographs starting to lose their distinction as they grow fuzzy. The film's most powerful recurring motif is bonding over eating noodles, something we see the characters do via editing even before they've met each other again.

It's all extraordinarily nice, something I was surely not prepared to encounter in a Miike yakuza film; whether a viewer in 2000 would be apt to have a preconceived notion of Miike that would give them a similar feeling of surprise, I could not say. But again, Audition already existed by this point, so it seems at least likely that this unabashed, unapologetic wallow in coziness and sentimentality is meant to be just as disorienting as I found it

If that's all there was to it, I have to imagine that DOA 2 would probably feel just as glib in its own way as the films its implicitly pushing against: it's schematic in a different way, but still ultimately schematic. But that's not all there is to it, in part because, for all that the center of the film is a lovely golden-hour meander through nourishing nostlagia, the edge of the film are still a garish sideshow. It's a splashily violent film, in the most literal sense of "splashy": there's a particularly striking angle of someone being shot that we see quite early in the film where a huge splatter of stage blood goes right across the camera lens. It's also a film where one character has a huge penis, three feet long and as thick as a railroad tie, which he heaves around laboriously while the film feebly attempts to use pixelization to unsuccessfully prevent us from seeing it. There's a lot of broad, aggressively sophomoric humor, in other words (and heck, calling some of it "humor" is potentially giving it too much benefit of the doubt. The pixelated dick is for sure a deliberately gag, though). There's a lot of pointedly sick-minded material here, I think as much because Miike just finds it pleasant and fun to include that material as because he's trying to "do something" with it. That being said, there is something being done: the contrast between all of this excessive, tawdry material and the nucleus of friendship and humanity living in that main plot never stops being much weirder than the excess would in its own right.

And in the end, Miike provokes us one last time, with a downbeat ending that jettisons both the sentiment and the garish genre pyrotechnics for a finale that strips out everything but the cold facts of violence and suffering. That, of course, is where Dead or Alive 2: Birds was always going to take us, with all of that steely moralism being built into its middle: all of the warm charm and all of the trashy prurience alike were just setting up for one ably-placed sucker punch. And sure, this all ends up boiling down to the hardly-revelatory announcement that a life lived in violence will tend to be ruined by that violence, but sometimes, it's more about the sprawling way a film gets us to its final word than it what it actually says there. And this is quite a giddy, emotionally resonant journey.

Do you have a movie you'd like to see reviewed? This and other perks can be found on our Patreon page!

Miike Takashi's whole "thing", as I suppose most people who know two things about him are aware (if they know only one thing, it's probably that he's ludicrously prolific, making like ten films every year for a couple of decades), is that he likes to do bizarre and unexpected things that pitch the audience right out of our comfort zone with the genres he's working in. As it generally does, this is mainly used to mean "he makes fucked-up, edgy, violent things", not least because in the anglosphere, his best-known film after almost a quarter of a century remains the freaked-out torture porn/romcom hybrid Audition, one of the early entries in the international trend towards extreme horror content in upsetting psychological thrillers that made up a great deal of horror cinema in the 2000s.

Miike's not really a "horror director" though - with a filmography that deep and wide, he's not really an anything director, but has tried out everything up to and including cheerful family films - and I think it is good to have an occasional reminder that transgressing boundaries in art does not necessarily mean filling it full of lurid adults-only content. At which point I'll clarify that our present subject is an adults-only proposition, but only somewhat incidentally, and that's not what's transgressive about it. The film in question is 2000's Dead or Alive 2: Birds, the middle entry in a trilogy-in-name-only of films connected only by Miike and lead actors Aikawa Shō and Takeuchi Riki (the first two are both yakuza films; the third doesn't even make this modest nod to unity), and on paper, it feels like just another one of the high-concept gangster pictures that became ubiquitous across the globe in the decade after Reservoir Dogs and Pulp Fiction introduced. Mizuki (Aikawa) is an assassin, hired to some yakuza or another in an ongoing gang war. Just as he's about to take his shot, though, some else gets to the target first. And as Mizuki digs into this a bit, he discovers that the other man who was hired to do the same job is also operating under the name of Mizuki.

So far, so much high-energy boilerplate: dueling hitman, hired to do the same job and presumably therefore in competition. And it doesn't really have to get any less boilerplate when Mizuki A discovers that Mizuki B is actually his childhood friend Shuuichi (Takeuchi); criminals being confronted with the shadowy echoes of their past is a longstanding pillar of the gangster genre. No, where DOA 2 becomes suddenly very weird and considerably unusual is in what happens to the film itself when Mizuki and Shuuichi cross paths on the ferry to the island where they lived as children: it transforms into a quiet, contemplative character drama about nostalgia and whether the children we were would be proud of the adults we are.

And so, back to my initial point: Miike's wisdom as a transgressive artist doesn't lie in his ability to pile more and more revolting, shocking, sardonically nihilistic material in to the stuff of a gangster picture. Gangster pictures had gotten extremely good at that by 2000 without having provocateurs like Miike doing that. Instead, the provocation of DOA 2 is to situate all of these gangland shenanigans in a warmly human narrative context, one with an unmistakable moral bent on top of everything. Though thankfully not one it feels the need to grandstand about. The film is, to a startling degree, not glib; is has in fact a kind of anti-glibness that's made all the more concrete and vivid because the film does make some highly ironic gestures. Perhaps the most overt of these comes near the the climax, when the film cross-cuts between a play staged for an audience of squealing children, and the violent deaths of several yakuza. And, just for added measure, the children's play is full of lewd sexual imagery (though I'm not entirely confident it would play as lewdly to a Japanese viewer as to this American). So that's an ironic, leering juxtaposition packed into a second ironic, leering juxtaposition.

The thing is, though, by the time we get to this point in DOA 2, the easy contrast between manic actors mugging for a bunch of happily shrieking children and spectacular, gaudy violence feels kind of pat and obvious - kind of, as I was saying, glib, and I think that Miike has not done this by accident. And he's definitely not doing it just to be smugly above-it-all; there's a lot of boisterous energy here, and the actors playing the actors are really going for it. But it's not just a "cool" gesture, something about it feels a little unsettled and ugly, and I feel like that's what we've been set up with by the earlier parts of the movie; to find something grim and morbid in the contrast, not sarcastic and snotty. And so, the anti-glibness: the real contrast isn't between death and children's entertainment, but between that kind of of slick filmmaking and the good-natured, sluggish sentimentality of the film's extremely long middle.

And with that, why don't we skip back to the middle? Dead or Alive 2: Birds is a crisp 97 minutes long, and it's astounding how many of those minutes simply put the narrative on pause to allow Mizuki and Shu to sink into their childhood memories as they reconnect on their island, find their old childhood friend Kohei (Endo Kenichi) and his pregnant wife Chieko (Aota Noriko), and visit the orphanage where they grew up. Much of this involves grainy flashbacks, and most of it involves cinematographer Tanaka Kazunari treating the film to give the whole thing a heavy yellow glow, the warm, fading tone of old photographs starting to lose their distinction as they grow fuzzy. The film's most powerful recurring motif is bonding over eating noodles, something we see the characters do via editing even before they've met each other again.

It's all extraordinarily nice, something I was surely not prepared to encounter in a Miike yakuza film; whether a viewer in 2000 would be apt to have a preconceived notion of Miike that would give them a similar feeling of surprise, I could not say. But again, Audition already existed by this point, so it seems at least likely that this unabashed, unapologetic wallow in coziness and sentimentality is meant to be just as disorienting as I found it

If that's all there was to it, I have to imagine that DOA 2 would probably feel just as glib in its own way as the films its implicitly pushing against: it's schematic in a different way, but still ultimately schematic. But that's not all there is to it, in part because, for all that the center of the film is a lovely golden-hour meander through nourishing nostlagia, the edge of the film are still a garish sideshow. It's a splashily violent film, in the most literal sense of "splashy": there's a particularly striking angle of someone being shot that we see quite early in the film where a huge splatter of stage blood goes right across the camera lens. It's also a film where one character has a huge penis, three feet long and as thick as a railroad tie, which he heaves around laboriously while the film feebly attempts to use pixelization to unsuccessfully prevent us from seeing it. There's a lot of broad, aggressively sophomoric humor, in other words (and heck, calling some of it "humor" is potentially giving it too much benefit of the doubt. The pixelated dick is for sure a deliberately gag, though). There's a lot of pointedly sick-minded material here, I think as much because Miike just finds it pleasant and fun to include that material as because he's trying to "do something" with it. That being said, there is something being done: the contrast between all of this excessive, tawdry material and the nucleus of friendship and humanity living in that main plot never stops being much weirder than the excess would in its own right.

And in the end, Miike provokes us one last time, with a downbeat ending that jettisons both the sentiment and the garish genre pyrotechnics for a finale that strips out everything but the cold facts of violence and suffering. That, of course, is where Dead or Alive 2: Birds was always going to take us, with all of that steely moralism being built into its middle: all of the warm charm and all of the trashy prurience alike were just setting up for one ably-placed sucker punch. And sure, this all ends up boiling down to the hardly-revelatory announcement that a life lived in violence will tend to be ruined by that violence, but sometimes, it's more about the sprawling way a film gets us to its final word than it what it actually says there. And this is quite a giddy, emotionally resonant journey.