It was the summer of '69

There is a moment in Summer of Soul (...Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised) , about 57 minutes into the 118-minute film, where we see something that is not at all meaningful in and of itself: in the middle of a performance of "I Heard it Through the Grapevine" by Gladys Knight & The Pips the film cuts to a shot from stage left, to fidnd the camera has canted heavily to one side, showing the group seeming to sing and dance on the edge of a steep precipice. It's hard to say if it's a random, tiny error in cinematography, caused by God knows what, or maybe the camera operator decided to be a bit feisty, and stylish (later in the same performance, we see footage from the same angle that has been leveled, at any rate, and given the camera rigs we see infrequently in the film, it doesn't seem likely that it would have happened by accident). Doesn't matter. What's wonderful about is that it's a moment of human messiness that captures something powerfully specific and tiny about the energy coursing through the live musical performances held in Mt. Morris Park (now Marcus Garvey Park) in Harlem, New York in June, July, and August, 1969, during that year's incarnation of the short-lived Harlem Cultural Festival (of which the '69 edition was by far the most successful and influential). It's an unpolished moment that perfectly evokes the physicality of the stage, the cameras, the performance, the sheer tangible vibe of what was happening in that instant at that place in that neighborhood.

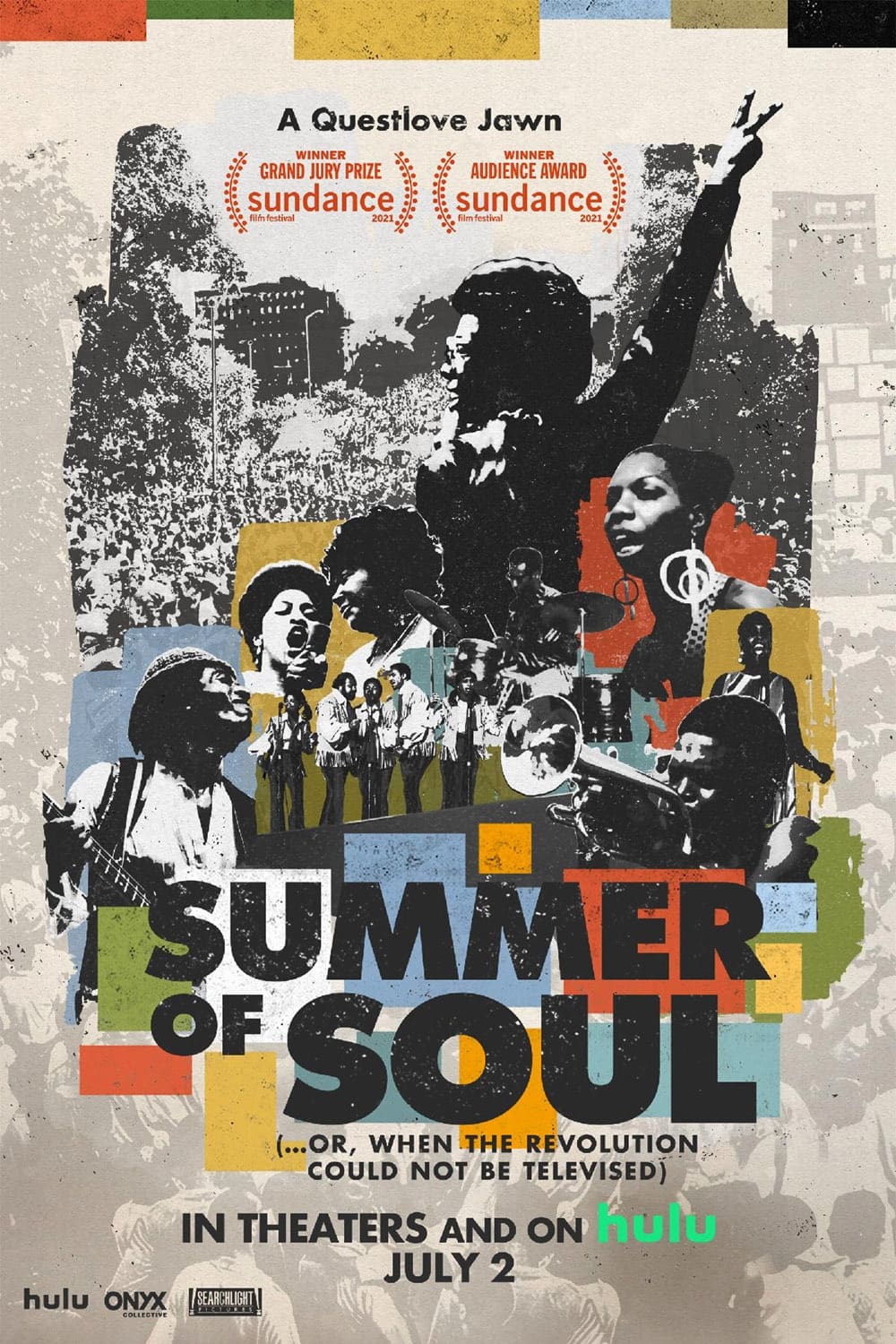

It would be a bit ludicrous to all it the "best" moment in Summer of Soul, which services as a concentrated delivery system for some of the most iconic African-American musical artists active in '69, many of them at the top of their game. But it feels weirdly special, because it's the one point in all of this that feels like the footage has escaped the confinement of the film. Summer of Soul is the newest and one of the most frustrating entries in my very least-favorite subgenre of documentary filmmaking, the "phenomenal footage that has been rather badly served by the way it has been assembled" picture. And this is particularly frustrating here since the marvelous quality of the footage is one of the main arguments that Summer of Soul is looking to make, right down to its subtitle. The festival's organiser, Tony Lawrence, hired Hal Tulchin, a local documentary filmmaker, to record performances from all six weekends, ending up with forty hours of footage all told, and that's sort of where things stopped. Summer of Soul (...Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised) would tell the story that the footage sat in a basement for 50 years, until Ahmir "Questlove" Thompson came to be aware of it, and decided to make his filmmaking debut by cleaning it up and presenting it to the world for the first time ever, and this isn't entirely true. Some of the footage was televised in 1969, some of the footage has cropped up unexpectedly here or thre, and the Nina Simone performance that Questlove very correctly decides needed to be the rousing climax to the whole thing has been rifled through for multiple Simone projects, including the 2015 Oscar nominee What Happened, Miss Simone?

But let us at least spot the film this much: it's extremely good footage, and it is very disappointing that it has been effectively invisible for half a century, and this obviously has a lot to do with the relative value ascribed to soul, gospel, rhythm & blues, and other African-American musical forms by the Caucasian-dominated commercial music industry. Summer of Soul insists right away that the Harlem Cultural Festival should be compared to the contemporaneous Woodstock Music and Art Fair, which of course has been one of the most heavily-mythologised events in the pop culture history of the post-WWII 20th Century. This is in some ways a smart rhetorical coup, and in some otherways an unforced error, but it's also trying to make this material smaller than it is: based on what we see here, the Harlem Cultural Festival looks to have been an unequivocally better festival than Woodstock, where several of the groups gave notoriously bad, even career-worst performances, and to judge from the 1970 documentary Woodstock, suffered as well from simply godawful sound projection. The media presented in Summer of Soul is, regardless of any other considerations, absolutely gorgeous: captured from a very effective array of angles, some of them impressively intimate and focused, and blessed with some drop-dead amazing recording for live music captured at an outdoor festival in '69. It is ear-slicingly clear, with terrific presence and a wide dynamic range that can capture everything from Mavis Staples launching into the high notes of the gospel standard "Take My Hand, Precious Lord" to percussive bass rumbling.

So no arguments: this is fantastic footage, worthy of any showcase that Questlove or any other filmmaker could possibly give it. Summer of Soul is decidedly not good enough for it. The situation is basically this: the concert series, coming in the summer of 1969 of all summers, was avowedly political in its aims, not just giving a platform to several great artists, but providing a fully-formed Black counterculture based in the unapologetic presentation of Black music in all of its forms. To that end, Summer of Soul ends up being less of a concert documentary about the Harlem Cultural Festival than it is a documentary about the state of the Black Power movement, circa August 1969, using the festival as a pretext. So the form that the film ends up taking is to present anywhere from about 15 seconds to about one minute of performance footage, and then to pull in a plethora of talking heads, mostly recorded new in 2019 and 2020, some culled from stock footage from the 1960s. Often they're explaining the meaning of the performance we're looking at. Often, they're just talking about the state of things in 1969, and the music is playing as a countermelody, basically. That's a perfectly legitimate approach to take to making a movie, but I cannot persuade myself that it's the most rewarding thing to do with this specific material.

First and most crucially, it demonstrates a terrified lack of faith in the performances to actually speak for themselves. That's not always unfair. Hearing the members of The Fifth Dimension reminisce about how they stumbled into "Aquarius", and how appearing at the festival felt like a vital opportunity for them to remind the world that they were not, in fact, white people, that's not something we'd be able to get from listening to them sing (I have stacked the deck here: watching the Fifth Dimension watch themselves across the span of five decades is probably the point where the talking heads approach yields the most powerful results). But a lot of the time, it feels thoroughly superfluous. Does hearing e.g. Chris Rock or Lin-Manuel Miranda talk about the importance of giving musical voice to the Black experience tell us anything actually new? I contend that it does not. And then there's there's the flat-out insulting: Nina Simone's set speaks perfectly loudly for itself and speaks to the present moment just fine without having several people pipe up to drown her out and basically say exactly what she's saying, while she's saying it. At the point that you'd rather hear people talk about Nina Simone than hear Nina Simone in her own words, you have decided that endless, artless contextualisation is the point of the film, and Summer of Soul is the worse off for it.

And as to the film's omnipresent, though only rarely and cautiously voiced argument that the burial of this footage prevented it from being a Woodstock-sized cultural event, I can only offer the question: yeah, but what the fuck did Woodstock achieve besides giving Baby Boomers an insanely outsized confidence that you're doing political activism by listening to music? If Questlove's argument is, sincerely, that the Harlem Cultural Festival should have had the impact of Woodstock, he's basically arguing that it should have been a superficial pose that changed absolutely nothing about the world in which we live but served as some unbearably potent nostalgia fodder, and I am 100% sure he's not trying to make that argument. Anyway, I have to ask the question: must music be politically revolutionary? Can't it just be remarkably and powerfully artful, giving voice to a whole universe of feeling from the radically angry to the buoyantly celebratory, in modes from bombastic energy to laser-focused virtuosity?

Because Summer of Soul has music that's all of that and more. When the onslaught of talking heads shuts up and lets the music play out at some length, and the quiet passages are full of crowd noises and not tepid voiceover, and we actually see the beginning and middle and end of performances all in one place, this is some of the most electrifying live footage you'll ever see, performed by people charged up by the unshakeable confidence that what they're doing in this moment truly matters (justifiably or not, that's besides the point). Now that it's out in the world, I hope we get to see more of it, and assembled with less of a wobbly hand, one that won't overindulge on cross-dissolves and reducing entire acts to montages, on top of all the endless talking heads. Because the revolution still hasn't been televised, frankly, not in this format, and it's mildly vexing that a film so righteously angry that the voices of these artists have been covered up is still doing such a poor job of letting them speak for themselves.

It would be a bit ludicrous to all it the "best" moment in Summer of Soul, which services as a concentrated delivery system for some of the most iconic African-American musical artists active in '69, many of them at the top of their game. But it feels weirdly special, because it's the one point in all of this that feels like the footage has escaped the confinement of the film. Summer of Soul is the newest and one of the most frustrating entries in my very least-favorite subgenre of documentary filmmaking, the "phenomenal footage that has been rather badly served by the way it has been assembled" picture. And this is particularly frustrating here since the marvelous quality of the footage is one of the main arguments that Summer of Soul is looking to make, right down to its subtitle. The festival's organiser, Tony Lawrence, hired Hal Tulchin, a local documentary filmmaker, to record performances from all six weekends, ending up with forty hours of footage all told, and that's sort of where things stopped. Summer of Soul (...Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised) would tell the story that the footage sat in a basement for 50 years, until Ahmir "Questlove" Thompson came to be aware of it, and decided to make his filmmaking debut by cleaning it up and presenting it to the world for the first time ever, and this isn't entirely true. Some of the footage was televised in 1969, some of the footage has cropped up unexpectedly here or thre, and the Nina Simone performance that Questlove very correctly decides needed to be the rousing climax to the whole thing has been rifled through for multiple Simone projects, including the 2015 Oscar nominee What Happened, Miss Simone?

But let us at least spot the film this much: it's extremely good footage, and it is very disappointing that it has been effectively invisible for half a century, and this obviously has a lot to do with the relative value ascribed to soul, gospel, rhythm & blues, and other African-American musical forms by the Caucasian-dominated commercial music industry. Summer of Soul insists right away that the Harlem Cultural Festival should be compared to the contemporaneous Woodstock Music and Art Fair, which of course has been one of the most heavily-mythologised events in the pop culture history of the post-WWII 20th Century. This is in some ways a smart rhetorical coup, and in some otherways an unforced error, but it's also trying to make this material smaller than it is: based on what we see here, the Harlem Cultural Festival looks to have been an unequivocally better festival than Woodstock, where several of the groups gave notoriously bad, even career-worst performances, and to judge from the 1970 documentary Woodstock, suffered as well from simply godawful sound projection. The media presented in Summer of Soul is, regardless of any other considerations, absolutely gorgeous: captured from a very effective array of angles, some of them impressively intimate and focused, and blessed with some drop-dead amazing recording for live music captured at an outdoor festival in '69. It is ear-slicingly clear, with terrific presence and a wide dynamic range that can capture everything from Mavis Staples launching into the high notes of the gospel standard "Take My Hand, Precious Lord" to percussive bass rumbling.

So no arguments: this is fantastic footage, worthy of any showcase that Questlove or any other filmmaker could possibly give it. Summer of Soul is decidedly not good enough for it. The situation is basically this: the concert series, coming in the summer of 1969 of all summers, was avowedly political in its aims, not just giving a platform to several great artists, but providing a fully-formed Black counterculture based in the unapologetic presentation of Black music in all of its forms. To that end, Summer of Soul ends up being less of a concert documentary about the Harlem Cultural Festival than it is a documentary about the state of the Black Power movement, circa August 1969, using the festival as a pretext. So the form that the film ends up taking is to present anywhere from about 15 seconds to about one minute of performance footage, and then to pull in a plethora of talking heads, mostly recorded new in 2019 and 2020, some culled from stock footage from the 1960s. Often they're explaining the meaning of the performance we're looking at. Often, they're just talking about the state of things in 1969, and the music is playing as a countermelody, basically. That's a perfectly legitimate approach to take to making a movie, but I cannot persuade myself that it's the most rewarding thing to do with this specific material.

First and most crucially, it demonstrates a terrified lack of faith in the performances to actually speak for themselves. That's not always unfair. Hearing the members of The Fifth Dimension reminisce about how they stumbled into "Aquarius", and how appearing at the festival felt like a vital opportunity for them to remind the world that they were not, in fact, white people, that's not something we'd be able to get from listening to them sing (I have stacked the deck here: watching the Fifth Dimension watch themselves across the span of five decades is probably the point where the talking heads approach yields the most powerful results). But a lot of the time, it feels thoroughly superfluous. Does hearing e.g. Chris Rock or Lin-Manuel Miranda talk about the importance of giving musical voice to the Black experience tell us anything actually new? I contend that it does not. And then there's there's the flat-out insulting: Nina Simone's set speaks perfectly loudly for itself and speaks to the present moment just fine without having several people pipe up to drown her out and basically say exactly what she's saying, while she's saying it. At the point that you'd rather hear people talk about Nina Simone than hear Nina Simone in her own words, you have decided that endless, artless contextualisation is the point of the film, and Summer of Soul is the worse off for it.

And as to the film's omnipresent, though only rarely and cautiously voiced argument that the burial of this footage prevented it from being a Woodstock-sized cultural event, I can only offer the question: yeah, but what the fuck did Woodstock achieve besides giving Baby Boomers an insanely outsized confidence that you're doing political activism by listening to music? If Questlove's argument is, sincerely, that the Harlem Cultural Festival should have had the impact of Woodstock, he's basically arguing that it should have been a superficial pose that changed absolutely nothing about the world in which we live but served as some unbearably potent nostalgia fodder, and I am 100% sure he's not trying to make that argument. Anyway, I have to ask the question: must music be politically revolutionary? Can't it just be remarkably and powerfully artful, giving voice to a whole universe of feeling from the radically angry to the buoyantly celebratory, in modes from bombastic energy to laser-focused virtuosity?

Because Summer of Soul has music that's all of that and more. When the onslaught of talking heads shuts up and lets the music play out at some length, and the quiet passages are full of crowd noises and not tepid voiceover, and we actually see the beginning and middle and end of performances all in one place, this is some of the most electrifying live footage you'll ever see, performed by people charged up by the unshakeable confidence that what they're doing in this moment truly matters (justifiably or not, that's besides the point). Now that it's out in the world, I hope we get to see more of it, and assembled with less of a wobbly hand, one that won't overindulge on cross-dissolves and reducing entire acts to montages, on top of all the endless talking heads. Because the revolution still hasn't been televised, frankly, not in this format, and it's mildly vexing that a film so righteously angry that the voices of these artists have been covered up is still doing such a poor job of letting them speak for themselves.

Categories: concert films, documentaries, message pictures, music