His love is real. He is not.

Setting aside the question the question of whether the end results are actually worth it - my answer would be "mostly, yes" - one must give After Yang the unhesitating credit that it is a complete work of narrative cinema, in which every element of the image and sound has been carefully positioned to work harmoniously towards the expression of a tightly-controlled set of emotions that derive from, and shape our response to, the story being told in the script. There's absolutely no reason for any of this to be remarkable or praiseworthy, but we live in a fallen age, and as I sat watching the film - the second feature directed by video essayist Kogonada, after 2017's Columbus - what kept wowing me over and over through the film's 96 minutes was how impeccable it all felt; nothing out of place, nothing done by accident, nothing that failed to serve as a little fractal representation of the whole. Being impeccable isn't the first thing everyone looks for out of a movie, and in this case, I'm not altogether sure that it's what I was looking for, but there's an undeniable joy in seeing a film come together just so to build a sophisticated, layered set of concepts and feelings all working below the surface of the story to create the most evocative possible version of that story.

Part of where I get to admiring the hell out of the movie without much loving it all is that the script for After Yang, adapted by Kogonada from Alexander Weinstein's short story "Saying Goodbye to Yang" from the 2016 science fiction collection Children of the New World, is built around one of the most routine, by-the-books sci-fi conceits imaginable. The whole result is like watching a chef trained in molecular gastronomy spend hours of time and effort carefully handcrafting a flawlessly symmetrical grilled cheese sandwich. Yes, it's tasty, but even the very best version of it comes as absolutely no surprise, and you have to wonder at a point if you couldn't have gotten something equally as delicious faster and with much less visible effort. In this case, the story is set at some point in the middle-distant future; the year is purposefully kept obscure, but the sets and clothing (both designed, by Alexandra Schaller and Arjun Bhasin respectively, to suggest a post-industrial embrace of eco-friendly, renewable construction techniques; it's done so subtly that I don't see how you could possibly notice it if you weren't armed with that knowledge in advance) all say "at least several years from now", and the implied geopolitical situation says "at least a few decades from now". And the way that we keep learning about this world, and in particular the relationship between what are presently called the United States and China in this world, is the most elegantly subtle and small element of a very subtle screenplay - often it's a clause in a sentence designed to be explaining a completely different situation that lets us know what's happening. Suffice it to say, there has been some large influx of Chinese-born infants to wealthy U.S. families in the recent past, with a war between the two superpowers apparently residing far enough in the past that relations are normal, but recent enough that there's a lot of fraught soft power jockeying going on. Part of that soft power takes the form of perfectly human-seeming robots designed to serve as surrogate big siblings to teach the Chinese adoptees about their cultural heritage.

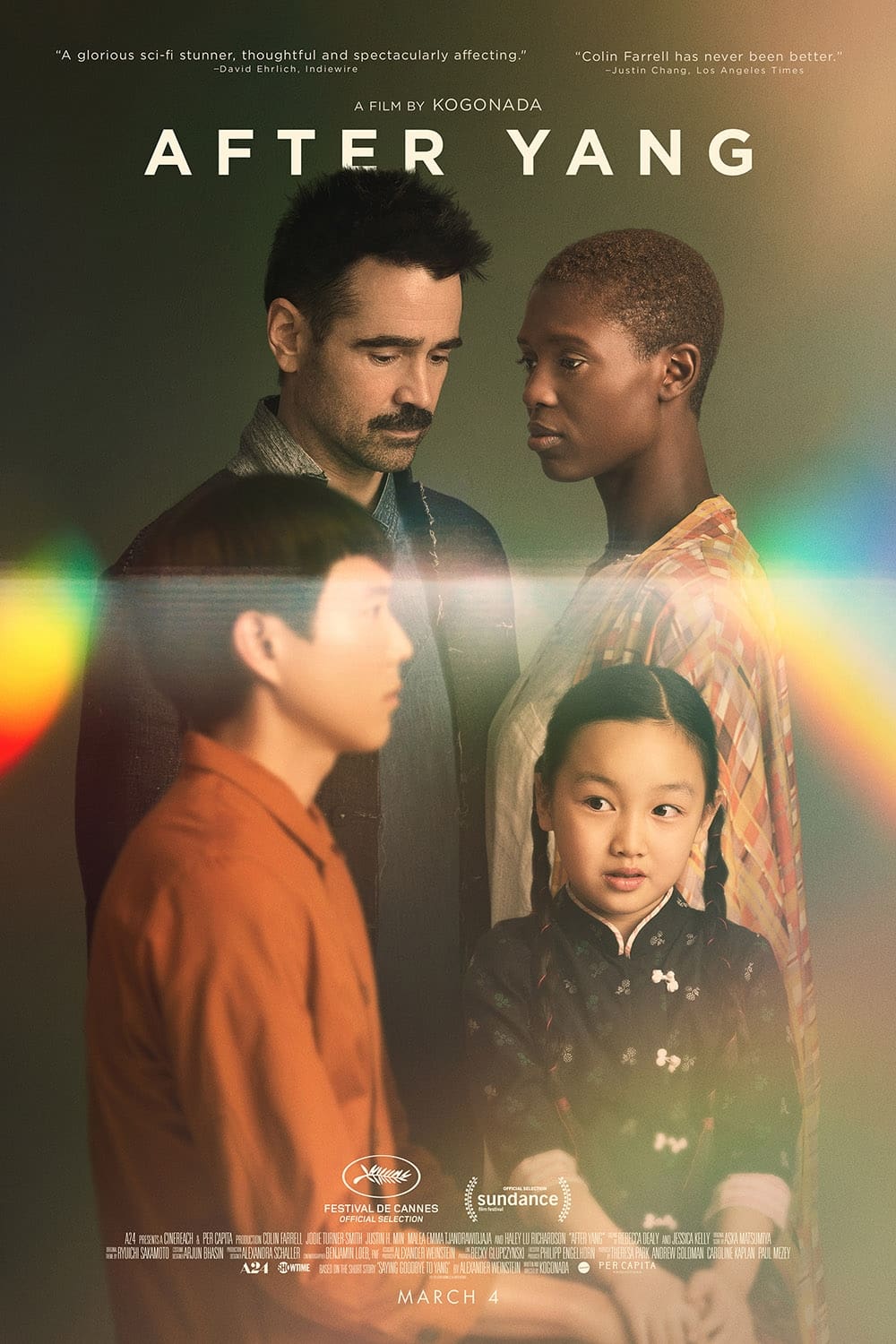

All of which resides far, far in the background of the actual story, which is that Jake (Colin Farrell) and Kyra (Jodie Turner-Smith) adopted Mika (Malea Emma Tjandrawidjaja) some years ago, and then a little while later purchased a secondhand robot, Yang (Justin H. Min) to keep her company as they go about their busy lives. Shortly after the film starts, Yang breaks, and there seems to be no good way to fix him, though after Jake has spent a few days storming around in an increasingly panicked frenzy, the possibility of at least recovering Yang's memories. And as he starts to sort through them, he discovers that Yang had perhaps a much richer life than the rest of the family knew about, and maybe a much richer life than was theoretically possible.

The genre-savvy among you already know where this is going, in terms of the ideas being plumbed if not the specifics of the narrative (which I will admit, kept me guessing, if only because I wasn't in the least expecting this solemn family drama to turn into a mystery partway through). First, the A.I. stuff: what does it, like mean to treat an object like a member of the family? Do simulated intelligences that can perfectly mimic human behavior in every visible and invisible way "count" as human? What happens when our programs turn out to be better at being themselves than being our tools? And then, the memory stuff: in a world where everything is recorded and can be replayed, what does it mean to conflate past experiences with viewing those memories in the present? If technology allows us to keep recycling the past, what is going to motivate us to let go of it and mourn what we've lost? Should we mourn what we've lost?

To the credit of everybody involved, After Yang never treats these chestnuts as stale, the kind of grist for stories about virtual people and virtual memories dating back for decades now. They are stale, but better by far to have a movie that takes them at face value and tries to build itself around grappling with them aesthetically, than one that just craps out some trite clichés. Still, the film expects us to do a lot of work to get to themes that the Star Trek franchise alone has covered a couple of dozen different times by now.

The main focus, anyway, isn't on the "robots: just like us?" material, and even less on the "so, what does it meant to be 'Chinese'?" material, but on the process of grieving and coping with loss, and feeling the hole created when someone who used to be in our life isn't any more. This is where the film's freshest and best material is, including the one big surprise: Kogonada (who edited as well as directing and writing) has fashioned a clever little trick to suggest how we get hung up on certain memories, by showing brief passages of scenes in flashback multiple times in a row, from different angles. Which also serves as a contrast to the couple of scenes of Jake scrubbing through Yang's memories, seeing the same dialogue multiple times from the same angle. It's clever, evocative, and - crucially - not at all overused, so it remains surprising and telling even the last times we see it crop up.

Other than that, After Yang mostly only offers extremely well-done versions of commonplace things. Kogonada and cinematographer Benjamin Loeb have created a series of precisely squared-off compositions, very much in keeping with the architectural compositions the director crafted in Columbus, and these give the film a distinctly airless, contained feeling; so does the perpetual low-lighting throughout. Both of these creep into the film only as it turns toward death and loss; the opening credits, in particular, are a shocking contrast to the rest, as we see groups of four figures performing rhythmic, patterned dance moves in empty spaces against backgrounds of solid color, all cut in brisk pace to the pulsing beat of a brightly urgent piece of throbbing music that stands far apart from the whispering hush that otherwise characteirses Aska Matsumiya's gorgeously dour score.

So, musically & visually, the film becomes heavy and hushed, and it has a perfect human embodiment in Farrell, who is the only person onscreen who really gets a fully-defined character to play (though several of the smaller roles are filled well). He's excellent at playing the non-emotive misery and dry-eyed sorrow that drive the film, and channeling it towards its slow shifts towards something less heavy.

Still, the film is not peppy - not slow-moving in the least, but pretty airless and grim, and including Farrell's performance, it tends to abstract everything, so it feels very intellectual on top of it. And while this remote feeling works, it makes After Yang seem somewhat more obscure than it needs to (again, it's making us do an awful lot of work to get some pretty standard robot shit). It also does the film very little good that it starts to over-invest in its mysterious backstory, involving a mysterious woman played by a purposefully opaque Haley Lu Richardson; the technology material is generally better as little bits of flavoring ("oh, that would be a privacy concern in the future!", that kind of thing), and it increasingly takes over as the film progresses. Still, what's never lost is the perfection of the compositions and the unity of the mood, the way that image and music and acting seem like facets of each other rather than constituent parts in a machine. It's an impressive, confident achievement, and while I think it shares a certain hermetic chilliness with Columbus, it confirms that Kogonada has one of the sharpest eyes of any new filmmaker out there.

Part of where I get to admiring the hell out of the movie without much loving it all is that the script for After Yang, adapted by Kogonada from Alexander Weinstein's short story "Saying Goodbye to Yang" from the 2016 science fiction collection Children of the New World, is built around one of the most routine, by-the-books sci-fi conceits imaginable. The whole result is like watching a chef trained in molecular gastronomy spend hours of time and effort carefully handcrafting a flawlessly symmetrical grilled cheese sandwich. Yes, it's tasty, but even the very best version of it comes as absolutely no surprise, and you have to wonder at a point if you couldn't have gotten something equally as delicious faster and with much less visible effort. In this case, the story is set at some point in the middle-distant future; the year is purposefully kept obscure, but the sets and clothing (both designed, by Alexandra Schaller and Arjun Bhasin respectively, to suggest a post-industrial embrace of eco-friendly, renewable construction techniques; it's done so subtly that I don't see how you could possibly notice it if you weren't armed with that knowledge in advance) all say "at least several years from now", and the implied geopolitical situation says "at least a few decades from now". And the way that we keep learning about this world, and in particular the relationship between what are presently called the United States and China in this world, is the most elegantly subtle and small element of a very subtle screenplay - often it's a clause in a sentence designed to be explaining a completely different situation that lets us know what's happening. Suffice it to say, there has been some large influx of Chinese-born infants to wealthy U.S. families in the recent past, with a war between the two superpowers apparently residing far enough in the past that relations are normal, but recent enough that there's a lot of fraught soft power jockeying going on. Part of that soft power takes the form of perfectly human-seeming robots designed to serve as surrogate big siblings to teach the Chinese adoptees about their cultural heritage.

All of which resides far, far in the background of the actual story, which is that Jake (Colin Farrell) and Kyra (Jodie Turner-Smith) adopted Mika (Malea Emma Tjandrawidjaja) some years ago, and then a little while later purchased a secondhand robot, Yang (Justin H. Min) to keep her company as they go about their busy lives. Shortly after the film starts, Yang breaks, and there seems to be no good way to fix him, though after Jake has spent a few days storming around in an increasingly panicked frenzy, the possibility of at least recovering Yang's memories. And as he starts to sort through them, he discovers that Yang had perhaps a much richer life than the rest of the family knew about, and maybe a much richer life than was theoretically possible.

The genre-savvy among you already know where this is going, in terms of the ideas being plumbed if not the specifics of the narrative (which I will admit, kept me guessing, if only because I wasn't in the least expecting this solemn family drama to turn into a mystery partway through). First, the A.I. stuff: what does it, like mean to treat an object like a member of the family? Do simulated intelligences that can perfectly mimic human behavior in every visible and invisible way "count" as human? What happens when our programs turn out to be better at being themselves than being our tools? And then, the memory stuff: in a world where everything is recorded and can be replayed, what does it mean to conflate past experiences with viewing those memories in the present? If technology allows us to keep recycling the past, what is going to motivate us to let go of it and mourn what we've lost? Should we mourn what we've lost?

To the credit of everybody involved, After Yang never treats these chestnuts as stale, the kind of grist for stories about virtual people and virtual memories dating back for decades now. They are stale, but better by far to have a movie that takes them at face value and tries to build itself around grappling with them aesthetically, than one that just craps out some trite clichés. Still, the film expects us to do a lot of work to get to themes that the Star Trek franchise alone has covered a couple of dozen different times by now.

The main focus, anyway, isn't on the "robots: just like us?" material, and even less on the "so, what does it meant to be 'Chinese'?" material, but on the process of grieving and coping with loss, and feeling the hole created when someone who used to be in our life isn't any more. This is where the film's freshest and best material is, including the one big surprise: Kogonada (who edited as well as directing and writing) has fashioned a clever little trick to suggest how we get hung up on certain memories, by showing brief passages of scenes in flashback multiple times in a row, from different angles. Which also serves as a contrast to the couple of scenes of Jake scrubbing through Yang's memories, seeing the same dialogue multiple times from the same angle. It's clever, evocative, and - crucially - not at all overused, so it remains surprising and telling even the last times we see it crop up.

Other than that, After Yang mostly only offers extremely well-done versions of commonplace things. Kogonada and cinematographer Benjamin Loeb have created a series of precisely squared-off compositions, very much in keeping with the architectural compositions the director crafted in Columbus, and these give the film a distinctly airless, contained feeling; so does the perpetual low-lighting throughout. Both of these creep into the film only as it turns toward death and loss; the opening credits, in particular, are a shocking contrast to the rest, as we see groups of four figures performing rhythmic, patterned dance moves in empty spaces against backgrounds of solid color, all cut in brisk pace to the pulsing beat of a brightly urgent piece of throbbing music that stands far apart from the whispering hush that otherwise characteirses Aska Matsumiya's gorgeously dour score.

So, musically & visually, the film becomes heavy and hushed, and it has a perfect human embodiment in Farrell, who is the only person onscreen who really gets a fully-defined character to play (though several of the smaller roles are filled well). He's excellent at playing the non-emotive misery and dry-eyed sorrow that drive the film, and channeling it towards its slow shifts towards something less heavy.

Still, the film is not peppy - not slow-moving in the least, but pretty airless and grim, and including Farrell's performance, it tends to abstract everything, so it feels very intellectual on top of it. And while this remote feeling works, it makes After Yang seem somewhat more obscure than it needs to (again, it's making us do an awful lot of work to get some pretty standard robot shit). It also does the film very little good that it starts to over-invest in its mysterious backstory, involving a mysterious woman played by a purposefully opaque Haley Lu Richardson; the technology material is generally better as little bits of flavoring ("oh, that would be a privacy concern in the future!", that kind of thing), and it increasingly takes over as the film progresses. Still, what's never lost is the perfection of the compositions and the unity of the mood, the way that image and music and acting seem like facets of each other rather than constituent parts in a machine. It's an impressive, confident achievement, and while I think it shares a certain hermetic chilliness with Columbus, it confirms that Kogonada has one of the sharpest eyes of any new filmmaker out there.