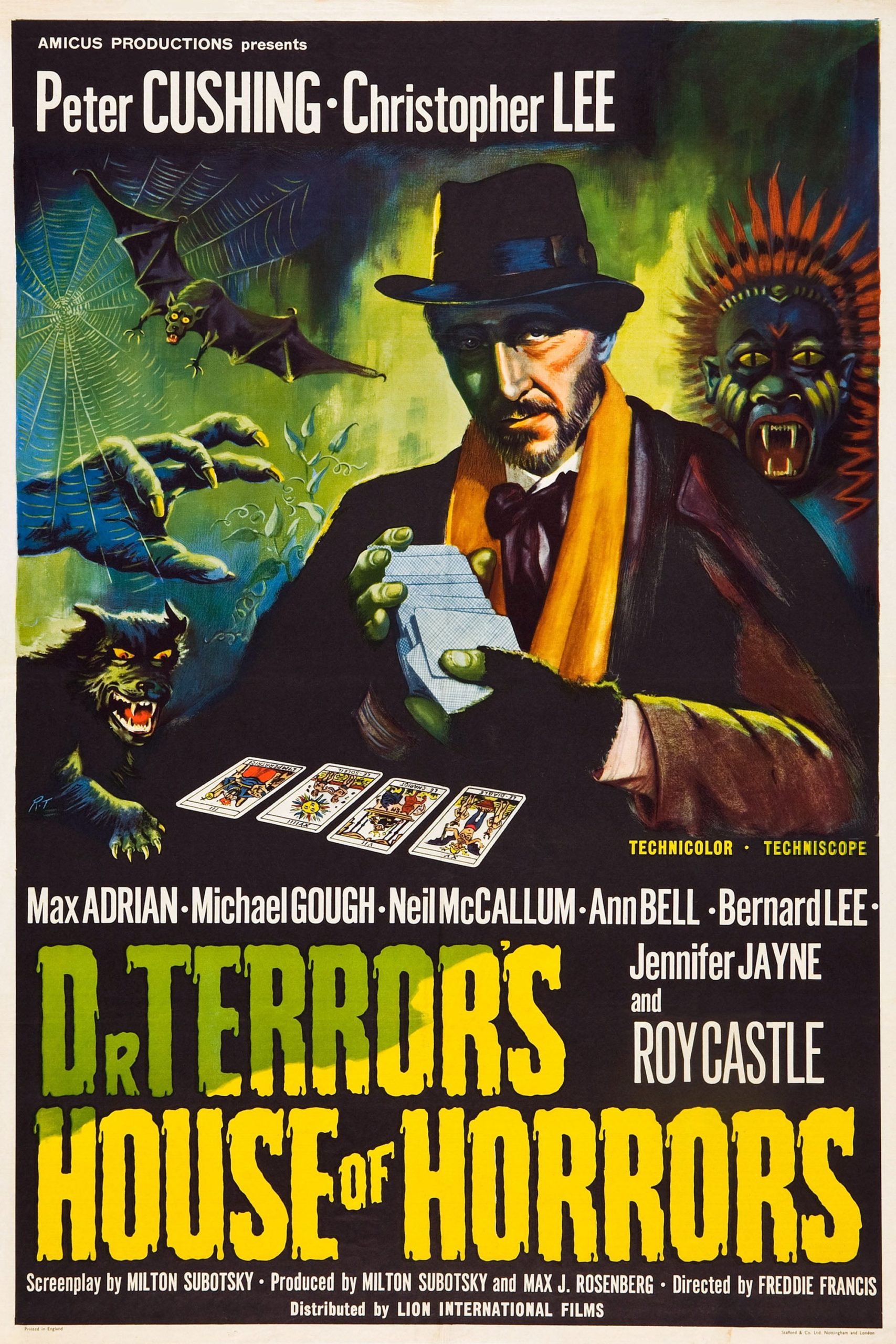

Amicus Horror: It's in the cards

Amicus Productions was only around a short time, from 1962 to 1977, and it produced a fairly small number of features, 28 in total (one of which it sold off rather than distribute under its own name). Despite this, it has one of the strongest reputations in the history of British genre film production. Of those 28 films, 16 of them are horror films, and seven - a full quarter of Amicus's entire output - are horror anthologies. And these anthology films, in particular, are regarded as one of the most classic bodies of horror cinema to come out of the 1960s and '70s.

Obviously, it didn't have to be thus. When it was first formed by American expatriates Milton Subotsky and Max Rosenberg, Amicus was just looking to make profitable movies of whatever sort it could. To that end, their first two films as Amicus were pure exploitation cinema in one of the '60s most reliably profitable genres: teen musicals. As far as I can tell, It's Trad, Dad! brought a huge return on its budget in 1962, and Just for Fun still turned a profit, albeit a smaller one, but this was not the director Amicus's heads wanted to keep going. And so, for their third movie, they turned to the only branch of exploitation cinema more reliably profitable than teenybopper trend-hopping: low-budget horror. And while I have said "it didn't have to be thus", it was still probably inevitable: Subotsky and Rosenberg were both fans of the genre, and had made their entry into the British film industry via the ultra-cheap Gothic The City of the Dead in 1960.

Now, trying to make a horror movie in Great Britain in the mid-'60s meant running square into the monolithic fact of Hammer Film Productions, a company that had, in the later half of the the 1950s, executed a slightly higher-budget version of the same turn that Amcius was in the process of attempting. In so doing, it had established itself as the major horror studio in the English-speaking world, creating a lock on the genre like no one company had since Universal in the 1930s. Amicus was never going to be able to compete with Hammer on an equal footing, so it came up with a couple of ways to carve a new niche for itself. One of these would be to leave Gothic horror to Hammer, as well as period trappings: every one of Amicus's 16 horror films is set in the modern day, inasmuch as we get evidence one way or the other. Hammer wouldn't make a similar jump until the 1970s, when they were essentially forced to by the collapse of the market for Gothics. The other was those anthology films, or "portmanteaus", as Amicus called them: a fine way to bundle several different stories all in one package, giving the viewer a little bit of everything. Subotsky was a great fan of the 1945 British anthology film Dead of Night, and he even suggested at times that his love of that film is what inspired him to take up writing short horror scripts in the first place.

Amicus's other big strategy was the exact opposite of they above: pilfering Hammer's talent pool. The anthology format undoubtedly helped with that: much easier to get a bigger name like Peter Cushing or Christopher Lee into the cast if you only need to pay them for a fifth of a movie, rather than a full movie. If this means that viewers ever since the films were new have sometimes conflated this or that Amicus film with the work of the bigger, more well-heeled studio... well, that could hardly have been a terrible outcome for Subotsky and Rosenberg.

All of this brings us, anyway, to 1965, when Amicus at long last jumped into producing horror films with Dr. Terror's House of Horrors, a "portmanteau" filled with five little tales of the paranormal that Subotsky had written back when he was first inspired by Dead of Night. This sets Dr. Terror apart from the six later Amicus anthology films, which were all based on adapting the work of specific authors or stories from specific magazines. Here, we instead get several O. Henry-esque tales of people experiencing some ironic twist that neatly dovetails with their naughty behavior.

But first, we get a framework narrative, and the big innovation that Amicus supplied to the horror anthology form: the framework is itself one of the creepy tales with an ironic twist, rather than just a box for the rest of the film. In this case, six men are sharing a train cabin leaving London; five of them are exactly the sort of staid Englisher you'd expect to see in such an environment, but the sixth is a colorful little eccentric who drops his valise, revealing a deck of Tarot cards. With four of the other five men having no clue what the hell these are, and the fifth finding them to be utter nonsense, the man has an opening to introduce himself and his work. His name is Dr. Schreck (Peter Cushing! See, I told you!), and he is a scholar of parapsychology and mysticism and all that. He notes that his name is German for "Terror", and jokingly claims that he calls his Tarot deck a "house of horrors" on account of how it tends to scare the people who are unprepared to encounter it, and thus, in its laborious way, we get the title.

Schreck convinces each of the five men in the cabin with him to undergo a Tarot reading, and hence we get the five stories that make up the rest of the film, which suggest the horrible destinies waiting for each of them. First up is Jim Dawson (Neil McCallum), who hears about what will happen when he arrives at his present destination, his old family manor in the Hebrides. He's fixing it up to sell it to the recently widowed Deirdre Biddulph (Ursula Howells), but is very annoyed to discover that one of the things that needs to be fixed is the whole in the wall that has revealed the burial place of the wicked Count Cosmo Valdemar, a reputed werewolf who was the original owner of the house, until he was killed by some ancestral Dawson. A longstanding legend holds that Valdemar will return to take his revenge on the Dawsons, and when a maid (Katy Wild) is found horribly murdered, Jim quickly jumps to the assumption that there might be something to that legend.

Once Jim's horrible fate is revealed - every one of the stories ends with the listener suffering a horrible fate of some sort - Schreck turns to Bill Rogers (Alan Freeman), and lets him know about the dreadful things that will happen to him at the conclusion of an upcoming family vacation. Climbing up the wall of his home, he and his wife Ann (Ann Bell) find a mysterious vine; a mysterious vine that seems to recoil in pain when Bill tries to cut it off, and even to defend itself violently. He immediately brings his story to a pair of government scientists, Hopkins (Bernard Lee) and Drake (Jeremy Kemp), and they find this a bit ludicrous, but the possibility of some strange new vine is too tempting to pass up. They're the first to learn just how far the vine is willing to go to protect itself. Or just to be a murderous asshole.

Next up is Biff Bailey (Roy Castle), an up-and-coming jazz musician who gets an opportunity to play some clubs in the Caribbean with his band. Because there's definitely call for white British jazz musicians to tour the Americas, I guess. One night, he meets a black man he takes to be a local, Sammy Coin (Kenny Lynch), who turns out to in fact be an English native himself. But Sammy knows enough of the area to accidentally let Biff know about a secret vodou ceremony happening outside of town. Biff immediately smells a chance to get some musical inspiration that's much more authentic than the watery jazz he's been playing, and against Sammy's warning, watches the ceremony from a distance, transcribing the chants he hears. He quickly gets found and thrown out, but he's able to hang onto the music, and creates a new arrangement to play when he gets back home. Unfortunately, he hasn't accounted for the possibility that the music in question will raise spirits he's not ready to control - spirits that, moreover, plainly don't take kindly to a dipshit white guy raising them.

At this point, the fellow passenger who has been huffing and puffing about what ridiculous nonsense this all is gets to huffing and puffing even louder. And so Schreck turns his attention this man next. He's art critic Franklyn Marsh (Lee), who has for whatever reason developed a huge vendetta against an artist by the name of Eric Landor (fellow Hammer veteran Michael Gough). He has taken such pleasure in wittily and merciless attacking Landor's work that the artist has finally decided to play a rather devious prank on him, right out in public. This makes Marsh even more haughty and angry still, and he makes the rather drastic turn from attacking Landor in print with his rapier wit, to attacking him on the street with his car. The subsequent attack leaves Landor alive but his hand must be cut off, and with that, his career as an artist is over. And, in short order, he kills himself. But his hand remains horribly alive, and it starts chasing Marsh for its own revenge.

The last passenger is an American, Dr. Bob Carroll (Donald Sutherland). He learns that the French woman he's thinking of proposing to, Nicolle (Jennifer Jayne) will say yes, and will move back to the United States with him, and whoopsie-doodle, that she's a vampire. Or, at least, the circumstantial evidence strongly suggests that this is the case, given that the small town where they live is suddenly beset with vampire-looking attacks right when she arrives. Bob asks his colleague, Dr. Blake (Max Adrian), for help in solving this vampiric mystery, and Blake's advice turns out be not very helpful in an extremely destructive way.

We have here the very rarest kind of anthology film: one without a weak link. It's definitely possible to rank these: I wouldn't hesitate to put "Creeping Vine" last (the chapters all have the most joylessly literal titles - "Werewolf", "Disembodied Hand", and so on), and this is almost entirely because it has to move way too fast to fit everything in; scenes don't transition, so much as we are bodily thrown from one location into the next, and Hopkins and Drake behave as they do not because it is in the character to do so, but because the film needs them to shift very fast if we're going to get to the climax on schedule. That's the other thing: these are all really short sequences. Dr. Terror runs to a total of just 98 minutes, which means that none of these even hits 20 minutes by itself; this means that all of them end up feeling more like sketches than fully developed stories. Oddly, this turns out to be a strength; it underlines the feeling that this is more about Schreck shocking his subjects with the inexplicable and inevitable chain of events that they'll hardly be able to comprehend before they stumble into their ironic fates. And given how Schreck's own story ends up, it's as likely that he's just taunting them as anything else.

As I was saying, though, there's not really a weak link, and it's even harder to pinpoint the best story than the worst (I'd put "Disembodied Hand" just a smidgen above "Vampire"; the former has Lee being haughty, the latter has a hell of a good final twist). The short running time of each segment probably has something to do with this; we drop in and out of each story so fast that they don't really register as separate things, and they all do feel like branches off of the story of that train compartment, rather than than that story feeling like a contrivance to get us at the individual segments.

Whatever the case, Dr. Terror has the very delightful feeling of binging several five-page short stories in a row, the kind that are mostly just there to set you up for a wallop, wallop you, and then end. Subotsky obviously loves these kind of stories, and he tells them with a whole lot of vigor and energy, which is by and large matched by the filmmaking. These are pretty silly tales, all things considered, and the film knows this; but they're also treated with a kind of seriousness that means it's not just being played for parody. Adrian's performance in the last story is maybe the clearest example of this: his character is ridiculous at pretty much every turn (the brevity of the story means that his man of science has to go to "oh, probably vampires" basically right away), and gets more so the deeper into the sequence we go, and he plays the part with an obviously little twinkle of a hammy showman. But he also takes seriously the death and mystery and gloom that hover over the whole thing. Different actors make the same balance in different ways: Lee's performance of genuine heart-palpitating panic at seeing the hand out of the corner of his eye is gripping and devoid of even the smallest hint of camp; Castle treats Biff as a big jolly idiot who has been in need of a comeuppance for much longer than just this story. I can't even really describe what the hell Cushing is up to, with his chirpy, elfin German accent and his freaky stares, which are all the freakier since he gets almost nothing but close-ups. It's both the goofiest part of the movie and the most threatening.

Overseeing all of this is director Freddie Francis, another Hammer mainstay who was about to become an Amicus mainstay: he would end up directing seven of their 28 features. But more than that, he was one of the greatest cinematographers of his generation (in fact, 1965 was the first year of his retirement from cinematography, until David Lynch brought him back 15 years later with The Elephant Man), and Dr. Terror is visibly the kind of film that happens when a cinematographer takes to directing. There are a great many unexpectedly complicated compositions in the film, places where Francis and the film's actual cinematographer, Alan Hume, play around with deep focus to make the film's different planes of action all bounce off of each other in interesting ways. The best of this happens in the framing narrative, as they concoct different methods of keeping the attention focused on Schreck, weighting him heavily in group shots, lighting Cushing slightly differently than the rest of the cast, giving him lots of sharp, bright close-ups where we can see every hair of his wispy mustache and beard. But even elsewhere, the film gets a huge kick out of filling spaces with light and bodies; it's a very busy film, crammed full of lively stuff.

This focus on cinematography has the very happy side effect of making the film look richer than it is. You don't see this kind of elaborate work in a cheap production, after all, so the fact that it's all over Dr. Terror acts as a kind of mental override, insisting that what we're looking at must be lavish, no matter how scrawny the sets look, sometimes. That, plus the extreme confidence of every single member of the cast, makes this feel quite a bit more polished and classy than it has any reason to be, especially given how knowingly schlocky it is. That combination of schlock and class is a wonderful sweet spot for any horror film to land in, and by getting to that point so ready, Dr. Terror makes a great argument that Amicus was ready to play in the horror big leagues, even with its first time at bat.

Obviously, it didn't have to be thus. When it was first formed by American expatriates Milton Subotsky and Max Rosenberg, Amicus was just looking to make profitable movies of whatever sort it could. To that end, their first two films as Amicus were pure exploitation cinema in one of the '60s most reliably profitable genres: teen musicals. As far as I can tell, It's Trad, Dad! brought a huge return on its budget in 1962, and Just for Fun still turned a profit, albeit a smaller one, but this was not the director Amicus's heads wanted to keep going. And so, for their third movie, they turned to the only branch of exploitation cinema more reliably profitable than teenybopper trend-hopping: low-budget horror. And while I have said "it didn't have to be thus", it was still probably inevitable: Subotsky and Rosenberg were both fans of the genre, and had made their entry into the British film industry via the ultra-cheap Gothic The City of the Dead in 1960.

Now, trying to make a horror movie in Great Britain in the mid-'60s meant running square into the monolithic fact of Hammer Film Productions, a company that had, in the later half of the the 1950s, executed a slightly higher-budget version of the same turn that Amcius was in the process of attempting. In so doing, it had established itself as the major horror studio in the English-speaking world, creating a lock on the genre like no one company had since Universal in the 1930s. Amicus was never going to be able to compete with Hammer on an equal footing, so it came up with a couple of ways to carve a new niche for itself. One of these would be to leave Gothic horror to Hammer, as well as period trappings: every one of Amicus's 16 horror films is set in the modern day, inasmuch as we get evidence one way or the other. Hammer wouldn't make a similar jump until the 1970s, when they were essentially forced to by the collapse of the market for Gothics. The other was those anthology films, or "portmanteaus", as Amicus called them: a fine way to bundle several different stories all in one package, giving the viewer a little bit of everything. Subotsky was a great fan of the 1945 British anthology film Dead of Night, and he even suggested at times that his love of that film is what inspired him to take up writing short horror scripts in the first place.

Amicus's other big strategy was the exact opposite of they above: pilfering Hammer's talent pool. The anthology format undoubtedly helped with that: much easier to get a bigger name like Peter Cushing or Christopher Lee into the cast if you only need to pay them for a fifth of a movie, rather than a full movie. If this means that viewers ever since the films were new have sometimes conflated this or that Amicus film with the work of the bigger, more well-heeled studio... well, that could hardly have been a terrible outcome for Subotsky and Rosenberg.

All of this brings us, anyway, to 1965, when Amicus at long last jumped into producing horror films with Dr. Terror's House of Horrors, a "portmanteau" filled with five little tales of the paranormal that Subotsky had written back when he was first inspired by Dead of Night. This sets Dr. Terror apart from the six later Amicus anthology films, which were all based on adapting the work of specific authors or stories from specific magazines. Here, we instead get several O. Henry-esque tales of people experiencing some ironic twist that neatly dovetails with their naughty behavior.

But first, we get a framework narrative, and the big innovation that Amicus supplied to the horror anthology form: the framework is itself one of the creepy tales with an ironic twist, rather than just a box for the rest of the film. In this case, six men are sharing a train cabin leaving London; five of them are exactly the sort of staid Englisher you'd expect to see in such an environment, but the sixth is a colorful little eccentric who drops his valise, revealing a deck of Tarot cards. With four of the other five men having no clue what the hell these are, and the fifth finding them to be utter nonsense, the man has an opening to introduce himself and his work. His name is Dr. Schreck (Peter Cushing! See, I told you!), and he is a scholar of parapsychology and mysticism and all that. He notes that his name is German for "Terror", and jokingly claims that he calls his Tarot deck a "house of horrors" on account of how it tends to scare the people who are unprepared to encounter it, and thus, in its laborious way, we get the title.

Schreck convinces each of the five men in the cabin with him to undergo a Tarot reading, and hence we get the five stories that make up the rest of the film, which suggest the horrible destinies waiting for each of them. First up is Jim Dawson (Neil McCallum), who hears about what will happen when he arrives at his present destination, his old family manor in the Hebrides. He's fixing it up to sell it to the recently widowed Deirdre Biddulph (Ursula Howells), but is very annoyed to discover that one of the things that needs to be fixed is the whole in the wall that has revealed the burial place of the wicked Count Cosmo Valdemar, a reputed werewolf who was the original owner of the house, until he was killed by some ancestral Dawson. A longstanding legend holds that Valdemar will return to take his revenge on the Dawsons, and when a maid (Katy Wild) is found horribly murdered, Jim quickly jumps to the assumption that there might be something to that legend.

Once Jim's horrible fate is revealed - every one of the stories ends with the listener suffering a horrible fate of some sort - Schreck turns to Bill Rogers (Alan Freeman), and lets him know about the dreadful things that will happen to him at the conclusion of an upcoming family vacation. Climbing up the wall of his home, he and his wife Ann (Ann Bell) find a mysterious vine; a mysterious vine that seems to recoil in pain when Bill tries to cut it off, and even to defend itself violently. He immediately brings his story to a pair of government scientists, Hopkins (Bernard Lee) and Drake (Jeremy Kemp), and they find this a bit ludicrous, but the possibility of some strange new vine is too tempting to pass up. They're the first to learn just how far the vine is willing to go to protect itself. Or just to be a murderous asshole.

Next up is Biff Bailey (Roy Castle), an up-and-coming jazz musician who gets an opportunity to play some clubs in the Caribbean with his band. Because there's definitely call for white British jazz musicians to tour the Americas, I guess. One night, he meets a black man he takes to be a local, Sammy Coin (Kenny Lynch), who turns out to in fact be an English native himself. But Sammy knows enough of the area to accidentally let Biff know about a secret vodou ceremony happening outside of town. Biff immediately smells a chance to get some musical inspiration that's much more authentic than the watery jazz he's been playing, and against Sammy's warning, watches the ceremony from a distance, transcribing the chants he hears. He quickly gets found and thrown out, but he's able to hang onto the music, and creates a new arrangement to play when he gets back home. Unfortunately, he hasn't accounted for the possibility that the music in question will raise spirits he's not ready to control - spirits that, moreover, plainly don't take kindly to a dipshit white guy raising them.

At this point, the fellow passenger who has been huffing and puffing about what ridiculous nonsense this all is gets to huffing and puffing even louder. And so Schreck turns his attention this man next. He's art critic Franklyn Marsh (Lee), who has for whatever reason developed a huge vendetta against an artist by the name of Eric Landor (fellow Hammer veteran Michael Gough). He has taken such pleasure in wittily and merciless attacking Landor's work that the artist has finally decided to play a rather devious prank on him, right out in public. This makes Marsh even more haughty and angry still, and he makes the rather drastic turn from attacking Landor in print with his rapier wit, to attacking him on the street with his car. The subsequent attack leaves Landor alive but his hand must be cut off, and with that, his career as an artist is over. And, in short order, he kills himself. But his hand remains horribly alive, and it starts chasing Marsh for its own revenge.

The last passenger is an American, Dr. Bob Carroll (Donald Sutherland). He learns that the French woman he's thinking of proposing to, Nicolle (Jennifer Jayne) will say yes, and will move back to the United States with him, and whoopsie-doodle, that she's a vampire. Or, at least, the circumstantial evidence strongly suggests that this is the case, given that the small town where they live is suddenly beset with vampire-looking attacks right when she arrives. Bob asks his colleague, Dr. Blake (Max Adrian), for help in solving this vampiric mystery, and Blake's advice turns out be not very helpful in an extremely destructive way.

We have here the very rarest kind of anthology film: one without a weak link. It's definitely possible to rank these: I wouldn't hesitate to put "Creeping Vine" last (the chapters all have the most joylessly literal titles - "Werewolf", "Disembodied Hand", and so on), and this is almost entirely because it has to move way too fast to fit everything in; scenes don't transition, so much as we are bodily thrown from one location into the next, and Hopkins and Drake behave as they do not because it is in the character to do so, but because the film needs them to shift very fast if we're going to get to the climax on schedule. That's the other thing: these are all really short sequences. Dr. Terror runs to a total of just 98 minutes, which means that none of these even hits 20 minutes by itself; this means that all of them end up feeling more like sketches than fully developed stories. Oddly, this turns out to be a strength; it underlines the feeling that this is more about Schreck shocking his subjects with the inexplicable and inevitable chain of events that they'll hardly be able to comprehend before they stumble into their ironic fates. And given how Schreck's own story ends up, it's as likely that he's just taunting them as anything else.

As I was saying, though, there's not really a weak link, and it's even harder to pinpoint the best story than the worst (I'd put "Disembodied Hand" just a smidgen above "Vampire"; the former has Lee being haughty, the latter has a hell of a good final twist). The short running time of each segment probably has something to do with this; we drop in and out of each story so fast that they don't really register as separate things, and they all do feel like branches off of the story of that train compartment, rather than than that story feeling like a contrivance to get us at the individual segments.

Whatever the case, Dr. Terror has the very delightful feeling of binging several five-page short stories in a row, the kind that are mostly just there to set you up for a wallop, wallop you, and then end. Subotsky obviously loves these kind of stories, and he tells them with a whole lot of vigor and energy, which is by and large matched by the filmmaking. These are pretty silly tales, all things considered, and the film knows this; but they're also treated with a kind of seriousness that means it's not just being played for parody. Adrian's performance in the last story is maybe the clearest example of this: his character is ridiculous at pretty much every turn (the brevity of the story means that his man of science has to go to "oh, probably vampires" basically right away), and gets more so the deeper into the sequence we go, and he plays the part with an obviously little twinkle of a hammy showman. But he also takes seriously the death and mystery and gloom that hover over the whole thing. Different actors make the same balance in different ways: Lee's performance of genuine heart-palpitating panic at seeing the hand out of the corner of his eye is gripping and devoid of even the smallest hint of camp; Castle treats Biff as a big jolly idiot who has been in need of a comeuppance for much longer than just this story. I can't even really describe what the hell Cushing is up to, with his chirpy, elfin German accent and his freaky stares, which are all the freakier since he gets almost nothing but close-ups. It's both the goofiest part of the movie and the most threatening.

Overseeing all of this is director Freddie Francis, another Hammer mainstay who was about to become an Amicus mainstay: he would end up directing seven of their 28 features. But more than that, he was one of the greatest cinematographers of his generation (in fact, 1965 was the first year of his retirement from cinematography, until David Lynch brought him back 15 years later with The Elephant Man), and Dr. Terror is visibly the kind of film that happens when a cinematographer takes to directing. There are a great many unexpectedly complicated compositions in the film, places where Francis and the film's actual cinematographer, Alan Hume, play around with deep focus to make the film's different planes of action all bounce off of each other in interesting ways. The best of this happens in the framing narrative, as they concoct different methods of keeping the attention focused on Schreck, weighting him heavily in group shots, lighting Cushing slightly differently than the rest of the cast, giving him lots of sharp, bright close-ups where we can see every hair of his wispy mustache and beard. But even elsewhere, the film gets a huge kick out of filling spaces with light and bodies; it's a very busy film, crammed full of lively stuff.

This focus on cinematography has the very happy side effect of making the film look richer than it is. You don't see this kind of elaborate work in a cheap production, after all, so the fact that it's all over Dr. Terror acts as a kind of mental override, insisting that what we're looking at must be lavish, no matter how scrawny the sets look, sometimes. That, plus the extreme confidence of every single member of the cast, makes this feel quite a bit more polished and classy than it has any reason to be, especially given how knowingly schlocky it is. That combination of schlock and class is a wonderful sweet spot for any horror film to land in, and by getting to that point so ready, Dr. Terror makes a great argument that Amicus was ready to play in the horror big leagues, even with its first time at bat.