Amicus Horror: All of them witches

This October, I'll be working my way through several of the films made by Amicus Productions, the second-most-beloved British horror film specialists of the 1960s and '70s. First up, though, is the film that was an Amicus film before Amicus existed.

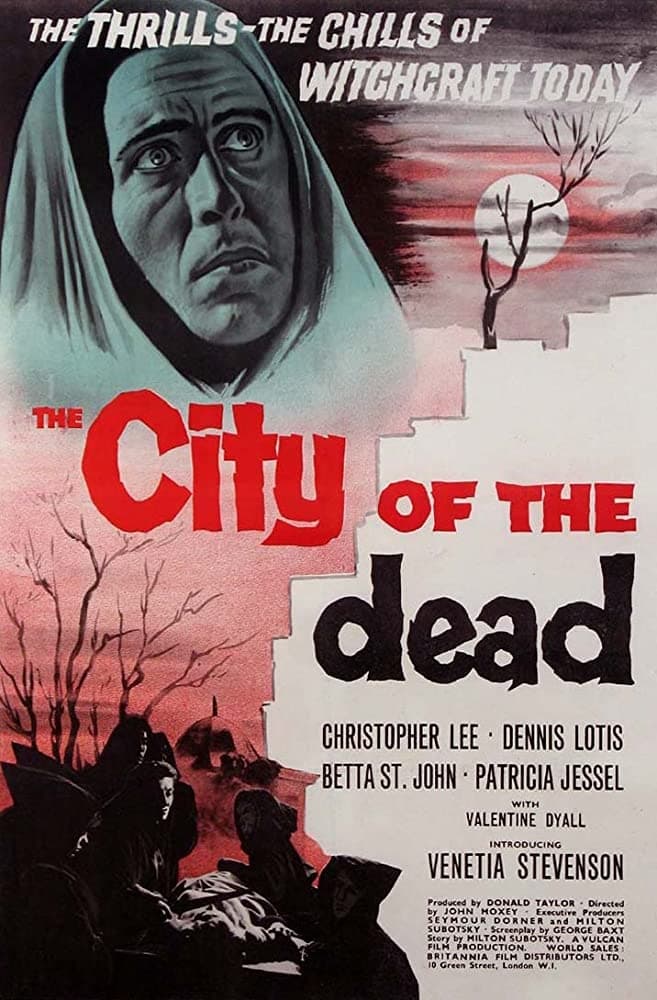

The film industries of the United Kingdom and the United States have always been awfully permeable, and in the form of 1960's The City of the Dead, we find an especially fun bit of transatlantic maneuvering. It's a British-made film and it has the feel of one, with the unmistakable coziness of something shot at Shepperton Studios, and an all-British cast bringing a distinctly classical approach to their roles. But it's an American screenplay on a quintessentially American subject and in a quintessentially American locale; though the way the themes are teased out - the conflict between the very old and the very young - takes on a particularly English-ish vibe. And the producers, Milton Subotsky and Max Rosenberg, were Americans who had seen success in America, making it a little unclear why they needed to find money on the far side of the ocean. Yet they found such success in migrating that they stayed to found a whole entire company, Amicus Productions, which would during its 15-year lifespan become one of the most recognisable names in British genre cinema - admittedly not a competitive field, but Amicus was also trying to carve out a reputation in territory that had been the exclusive domain of Hammer Film.

That's all in the wake of The City of the Dead, which had no such aspirations, of course (it was, for the record, not made by Amicus Productions, but by Vulcan Films - the only film in that company's history, and it has been customary to regard this as the proto-Amicus). It's not even particularly ambitious for a cheapie programmer: the budget was a ludicrously tiny ₤45,000, which was enough to pay for a running time of just 78 minutes, squarely in "the filler half of a double feature" territory. It started life as a television pilot written by George Baxt before Subotsky added enough new subplots to bring it up to a running time that could conceivably pass muster as a commercially-released feature. Even as such an incredibly little project with such unmistakably modest goals, it barely met them: it turned a profit (at the minuscule budget, it would be hard-pressed not to), but not much else, and it certainly didn't make the kind of in-roads into Hammer's territory that the filmmakers presumably hoped for.

This is a real pity, because even without making allowances for what B-horror is usually up to, The City of the Dead is a real treat, and almost impossibly for quickie genre film of this age, it completely blindsided me. In part, no doubt, because it acts so much like a generic programmer, lulling the viewer into assuming that we're watching one kind of thing, when we're actually watching something else entirely. I'm not even sure if the film knows that it's doing this. What this all means is that, 60 years old or not, I'm going to try very hard to talk around the film's plot, since I assume that if I had never heard anything about this film other than that it exists there's a good chance that you, my reader, have heard only the same amount, and I would not want to ruin the surprise for you.

We get right down to business, opening on a witch-burning: in Whitewood, Massachusetts, in 1692, a certain Elizabeth Selwyn (Patricia Jessel) has been found guilty of consorting with the man-goat, and is to be put to death. Before this happens, she and her fellow devil-worshipper, Jethrow Keane (Valentine Dyall), are able to spit out one last prayer to Lucifer, begging him to curse the town and give them eternal life. In the original cut, anyway. The American distributors, in 1962, snipped out these exact lines of dialogue, which set up pretty much the entire plot. Because we Yanks are apparently more sensitive about controversial material in our horror movies than the English, all of a sudden.

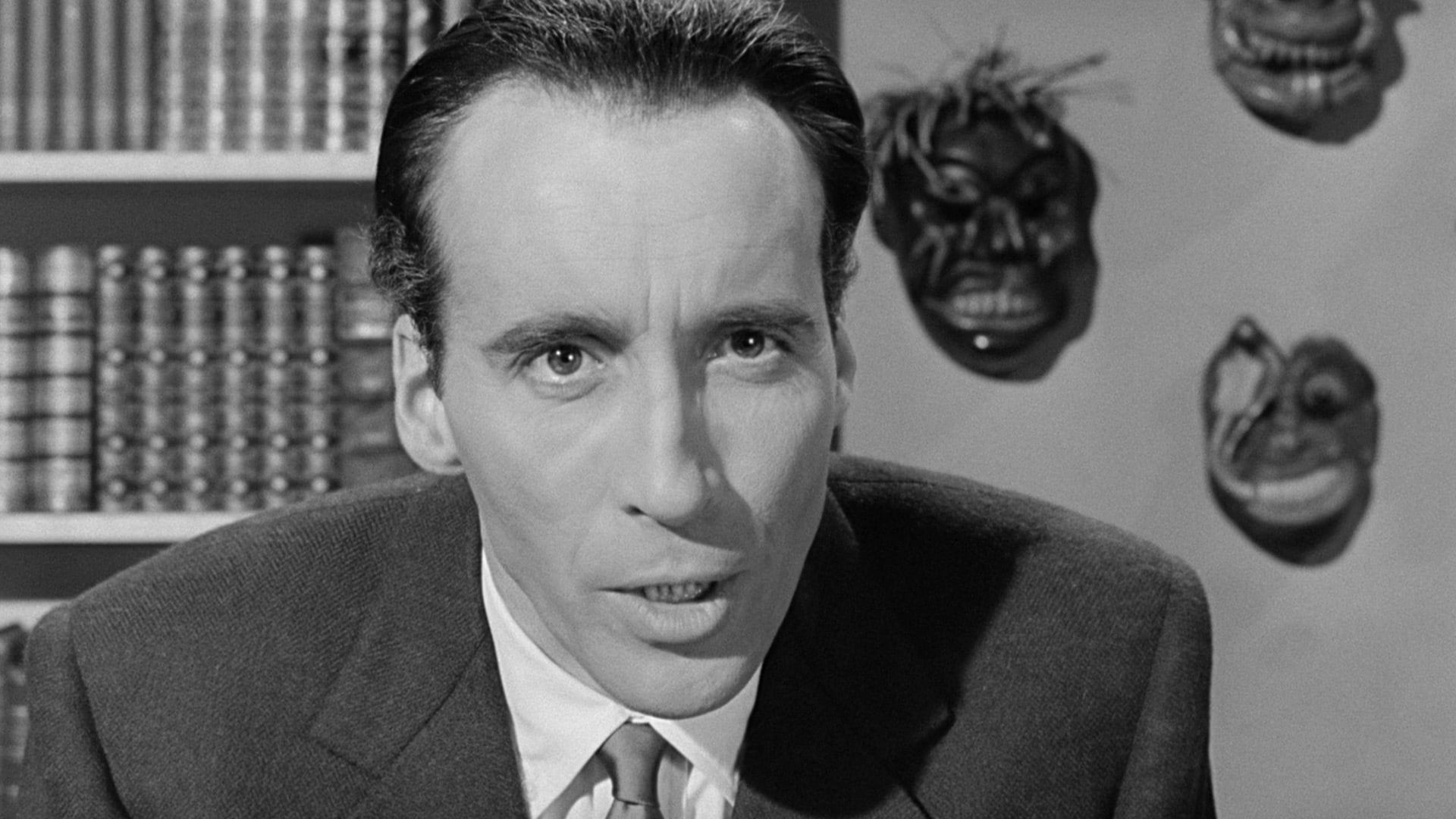

Anyway, the curse being invoked, we slam into the present day, where Elizabeth's dying word is being loudly and enthusiastically shouted by Alan Driscoll (Christopher Lee), a professor of history and folklore, at his mostly rapt class. The "mostly" is due to Bill Maitland (Tom Naylor), a science major whose conviction that all these "humanities" and "social sciences" are just so much hot wind leads him to declare, in just a couple of scenes, that all of this nonsense about "looking at documents" and "constructing historical narratives" is functionally indistinguishable from snake-handling. He doesn't use these words, but the sentiment is there. I had Thoughts about Bill Maitland, you might say. Anyway, Bill thinks that studying folklore is fucking ridiculous, and as Driscoll continues to wax rhetorical on the subject, he snidely announces "Dig that crazy beat" to his friends. This being, you see, an attempt to freshen up Gothic horror tropes for the 20th Century, unlike the musty old Victorianisms going on at Hammer; that means appealing to the youth, and in 1960, the youth, they "dug" things. And some of what they dug were "beats". I am being snarky because this is by far the dumbest thing that happens in the film, which speaks pretty highly of the film.

Bill's girlfriend, Nan Barlow (Venetia Stevenson) is also taking the class, and she's very much among the rapt: in fact, Nan is a history major, and has gotten so excited by Driscoll's story of a witch burning that she wants to use the upcoming school break to go on a little research trip to find some primary sources in the little New England towns where these witch traditions used to thrive. Driscoll recommends Whitewood, and gives her the names of some contacts, and off she goes.

We arrive in over-the-top-Gothic-spookshow territory even before Nan arrives in Whitewood: as she drives through the inky black night, just lousy with fog, she meets a traditional Nervous Innkeeper, though in this case, he is a Nervous Service Station Attendant (James Dyrenforth), and he tells her in the oblique way of such vaguely ominous doomsayers in Gothic horror movies that bad things happen to people who go to that miserable, forgotten town. And not much later, she picks up a hitchhiker, and wouldn't you know that the hitchhiker is a dead ringer for Jethrow Keane - he's even named Jethrow, which is our first sign of how well that prayer to Satan worked. In Whitewood, Jethrow apparently evaporates into mist while Nan isn't looking, and while this discomfits her, she's far too sensible to freak out. Instead, she heads right into the Raven's Inn and uses Driscoll's name to finagle a room out of the hostile proprietor, Mrs. Newless - and we get our second familiar face of the evening, since as her barely-disguised surname suggests, Mrs. Newless looks for all the world like the resurrected Elizabeth Selwyn. Nan doesn't know that, of course, so she takes the landlady's behavior as merely the unfriendly eccentricity of a rural New Englander, and spends the next day mucking around town, where the only person who isn't oozing menace is a woman about her own age, Patricia Russell (Betta St. John), who has only just returned to Whitewood after years away, to help her grandfather (Norman MacOwan), the blind and apparently slightly batty reverend in a town where a consecrated Christian church seems unusually incongruous.

Up to this point, The City of the Dead has held nothing back. Director John Llewellyn Moxey, making his first feature film, goes all-in on the thick, gloomy atmosphere, and despite the pittance of a budget, John Blezard put together some pretty delightfully shameless horror movie sets to let that atmosphere really sink all the way into your bones. Everything about Whitewood is suffused with the spirit of a rickety old haunted house, the kind with more enthusiasm than quality, from the omnipresent fog to the severely high contrast in Desmond Dickinson's lush black and white cinematography. It is frankly kitschy, and I was prepared to write it off as just kitsch right about this point. Immensely satisfying kitsch, I want to point out! The film's go-for-broke atmosphere was doing literally all of the work, but it was doing the work, and I'm not immune to the charms of a good attempt by a movie to ladle on fog, shout "boo!", and then we can both have a fine laugh about how playfully garish it all is. That took the sting out of how brutally predictable this all felt: the film is surprisingly non-specific in connecting Newless with Selwyn, and Jethrow 1 with Jethrow 2 (no music cues, no "aha!" camera angles), which made me wonder if it was somehow trying to make that a surprise (and there was, of course, the open question: are the reincarnated, immortal, or just the descendants of the dead witches?). There's also, of course, the matter of casting Christopher Lee in a throwaway role at the start of a story. Hammer was still using Lee as a character actor and second-banana at this point, which is probably why Vulcan Films was able to afford him as the "name". Still, even if Hammer wasn't letting him out from underneath Peter Cushing's shadow yet, he was still a big enough face that you know they wouldn't have given him such an empty, functional part as Driscoll if that character wasn't going to come back as part of some secret involving the witches in the film's back half. So I was pretty much comfortable in writing off The City of the Dead as some excellent atmosphere-on-a-budget covering up for the sins of an indifferent script and a bunch of actors who were all finding pretty much one note and hitting it (presumably, the rest of their brainpower went into maintaining their uncertain American accents - Stevenson and Naylor are probably better at it than the rest of the cast, and I will say that watching Lee turn his rich purring voice onto nasal Amerianisms is at least amusing, if not always convincing).

Well, I was wrong, and good for the film in suckering me in so completely. Oh, I wasn't wrong about what was happening - like, obviously Newless and Jethrow 2 are nefarious witches, obviously Driscoll has something to do with it, and whathaveyou. But I was wrong that the film didn't want me to notice that. The extreme obviousness of the plot, like the extreme obviousness of the style, is very much something the film is weaponising against us: as we're watching Nan obliviously plunge her way into this nest of witchery, we are, on some level, supposed to recognise that she's getting way the hell in over her head in the face of some incredibly unsubtle menace and villainy. The film ends up activating all those secrets I had been so bored to figure out much earlier than I expected, and in the space of one hell of a shocking and even upsetting graphic match cut, The City of the Dead has suddenly become something much more difficult and bold than I had assumed would be remotely possible for a tossed-off low-budget programmer: one of the boldest acts of narrative mindfuckery that 1960 was capable of producing, frankly. I will say nothing about what happens, or why the place that the film ends up is absolutely nothing like I was anticipating from the set-up, other than to suggest that this marriage of heaving Gothic style and brazenly modern storytelling is exactly the kind of aggressively fresh way of approaching horror that one hopes for from a pair of producers looking to make their mark in a generic landscape that's not looking to make room for them unless it is forced to do so. The film is still a bit kitschy and the low budget shows and the acting can be a bit stiff, but The City of the Dead honest-to-God shocked me, and I cannot remember the last time I had that reaction to something over half a century old, especially something in a mostly formulaic genre like Gothic horror. It's a complete delight in its spooky silliness, and I am officially outraged that it has no reputation to speak of beyond being the movie that happened before Amicus was a thing yet.

The film industries of the United Kingdom and the United States have always been awfully permeable, and in the form of 1960's The City of the Dead, we find an especially fun bit of transatlantic maneuvering. It's a British-made film and it has the feel of one, with the unmistakable coziness of something shot at Shepperton Studios, and an all-British cast bringing a distinctly classical approach to their roles. But it's an American screenplay on a quintessentially American subject and in a quintessentially American locale; though the way the themes are teased out - the conflict between the very old and the very young - takes on a particularly English-ish vibe. And the producers, Milton Subotsky and Max Rosenberg, were Americans who had seen success in America, making it a little unclear why they needed to find money on the far side of the ocean. Yet they found such success in migrating that they stayed to found a whole entire company, Amicus Productions, which would during its 15-year lifespan become one of the most recognisable names in British genre cinema - admittedly not a competitive field, but Amicus was also trying to carve out a reputation in territory that had been the exclusive domain of Hammer Film.

That's all in the wake of The City of the Dead, which had no such aspirations, of course (it was, for the record, not made by Amicus Productions, but by Vulcan Films - the only film in that company's history, and it has been customary to regard this as the proto-Amicus). It's not even particularly ambitious for a cheapie programmer: the budget was a ludicrously tiny ₤45,000, which was enough to pay for a running time of just 78 minutes, squarely in "the filler half of a double feature" territory. It started life as a television pilot written by George Baxt before Subotsky added enough new subplots to bring it up to a running time that could conceivably pass muster as a commercially-released feature. Even as such an incredibly little project with such unmistakably modest goals, it barely met them: it turned a profit (at the minuscule budget, it would be hard-pressed not to), but not much else, and it certainly didn't make the kind of in-roads into Hammer's territory that the filmmakers presumably hoped for.

This is a real pity, because even without making allowances for what B-horror is usually up to, The City of the Dead is a real treat, and almost impossibly for quickie genre film of this age, it completely blindsided me. In part, no doubt, because it acts so much like a generic programmer, lulling the viewer into assuming that we're watching one kind of thing, when we're actually watching something else entirely. I'm not even sure if the film knows that it's doing this. What this all means is that, 60 years old or not, I'm going to try very hard to talk around the film's plot, since I assume that if I had never heard anything about this film other than that it exists there's a good chance that you, my reader, have heard only the same amount, and I would not want to ruin the surprise for you.

We get right down to business, opening on a witch-burning: in Whitewood, Massachusetts, in 1692, a certain Elizabeth Selwyn (Patricia Jessel) has been found guilty of consorting with the man-goat, and is to be put to death. Before this happens, she and her fellow devil-worshipper, Jethrow Keane (Valentine Dyall), are able to spit out one last prayer to Lucifer, begging him to curse the town and give them eternal life. In the original cut, anyway. The American distributors, in 1962, snipped out these exact lines of dialogue, which set up pretty much the entire plot. Because we Yanks are apparently more sensitive about controversial material in our horror movies than the English, all of a sudden.

Anyway, the curse being invoked, we slam into the present day, where Elizabeth's dying word is being loudly and enthusiastically shouted by Alan Driscoll (Christopher Lee), a professor of history and folklore, at his mostly rapt class. The "mostly" is due to Bill Maitland (Tom Naylor), a science major whose conviction that all these "humanities" and "social sciences" are just so much hot wind leads him to declare, in just a couple of scenes, that all of this nonsense about "looking at documents" and "constructing historical narratives" is functionally indistinguishable from snake-handling. He doesn't use these words, but the sentiment is there. I had Thoughts about Bill Maitland, you might say. Anyway, Bill thinks that studying folklore is fucking ridiculous, and as Driscoll continues to wax rhetorical on the subject, he snidely announces "Dig that crazy beat" to his friends. This being, you see, an attempt to freshen up Gothic horror tropes for the 20th Century, unlike the musty old Victorianisms going on at Hammer; that means appealing to the youth, and in 1960, the youth, they "dug" things. And some of what they dug were "beats". I am being snarky because this is by far the dumbest thing that happens in the film, which speaks pretty highly of the film.

Bill's girlfriend, Nan Barlow (Venetia Stevenson) is also taking the class, and she's very much among the rapt: in fact, Nan is a history major, and has gotten so excited by Driscoll's story of a witch burning that she wants to use the upcoming school break to go on a little research trip to find some primary sources in the little New England towns where these witch traditions used to thrive. Driscoll recommends Whitewood, and gives her the names of some contacts, and off she goes.

We arrive in over-the-top-Gothic-spookshow territory even before Nan arrives in Whitewood: as she drives through the inky black night, just lousy with fog, she meets a traditional Nervous Innkeeper, though in this case, he is a Nervous Service Station Attendant (James Dyrenforth), and he tells her in the oblique way of such vaguely ominous doomsayers in Gothic horror movies that bad things happen to people who go to that miserable, forgotten town. And not much later, she picks up a hitchhiker, and wouldn't you know that the hitchhiker is a dead ringer for Jethrow Keane - he's even named Jethrow, which is our first sign of how well that prayer to Satan worked. In Whitewood, Jethrow apparently evaporates into mist while Nan isn't looking, and while this discomfits her, she's far too sensible to freak out. Instead, she heads right into the Raven's Inn and uses Driscoll's name to finagle a room out of the hostile proprietor, Mrs. Newless - and we get our second familiar face of the evening, since as her barely-disguised surname suggests, Mrs. Newless looks for all the world like the resurrected Elizabeth Selwyn. Nan doesn't know that, of course, so she takes the landlady's behavior as merely the unfriendly eccentricity of a rural New Englander, and spends the next day mucking around town, where the only person who isn't oozing menace is a woman about her own age, Patricia Russell (Betta St. John), who has only just returned to Whitewood after years away, to help her grandfather (Norman MacOwan), the blind and apparently slightly batty reverend in a town where a consecrated Christian church seems unusually incongruous.

Up to this point, The City of the Dead has held nothing back. Director John Llewellyn Moxey, making his first feature film, goes all-in on the thick, gloomy atmosphere, and despite the pittance of a budget, John Blezard put together some pretty delightfully shameless horror movie sets to let that atmosphere really sink all the way into your bones. Everything about Whitewood is suffused with the spirit of a rickety old haunted house, the kind with more enthusiasm than quality, from the omnipresent fog to the severely high contrast in Desmond Dickinson's lush black and white cinematography. It is frankly kitschy, and I was prepared to write it off as just kitsch right about this point. Immensely satisfying kitsch, I want to point out! The film's go-for-broke atmosphere was doing literally all of the work, but it was doing the work, and I'm not immune to the charms of a good attempt by a movie to ladle on fog, shout "boo!", and then we can both have a fine laugh about how playfully garish it all is. That took the sting out of how brutally predictable this all felt: the film is surprisingly non-specific in connecting Newless with Selwyn, and Jethrow 1 with Jethrow 2 (no music cues, no "aha!" camera angles), which made me wonder if it was somehow trying to make that a surprise (and there was, of course, the open question: are the reincarnated, immortal, or just the descendants of the dead witches?). There's also, of course, the matter of casting Christopher Lee in a throwaway role at the start of a story. Hammer was still using Lee as a character actor and second-banana at this point, which is probably why Vulcan Films was able to afford him as the "name". Still, even if Hammer wasn't letting him out from underneath Peter Cushing's shadow yet, he was still a big enough face that you know they wouldn't have given him such an empty, functional part as Driscoll if that character wasn't going to come back as part of some secret involving the witches in the film's back half. So I was pretty much comfortable in writing off The City of the Dead as some excellent atmosphere-on-a-budget covering up for the sins of an indifferent script and a bunch of actors who were all finding pretty much one note and hitting it (presumably, the rest of their brainpower went into maintaining their uncertain American accents - Stevenson and Naylor are probably better at it than the rest of the cast, and I will say that watching Lee turn his rich purring voice onto nasal Amerianisms is at least amusing, if not always convincing).

Well, I was wrong, and good for the film in suckering me in so completely. Oh, I wasn't wrong about what was happening - like, obviously Newless and Jethrow 2 are nefarious witches, obviously Driscoll has something to do with it, and whathaveyou. But I was wrong that the film didn't want me to notice that. The extreme obviousness of the plot, like the extreme obviousness of the style, is very much something the film is weaponising against us: as we're watching Nan obliviously plunge her way into this nest of witchery, we are, on some level, supposed to recognise that she's getting way the hell in over her head in the face of some incredibly unsubtle menace and villainy. The film ends up activating all those secrets I had been so bored to figure out much earlier than I expected, and in the space of one hell of a shocking and even upsetting graphic match cut, The City of the Dead has suddenly become something much more difficult and bold than I had assumed would be remotely possible for a tossed-off low-budget programmer: one of the boldest acts of narrative mindfuckery that 1960 was capable of producing, frankly. I will say nothing about what happens, or why the place that the film ends up is absolutely nothing like I was anticipating from the set-up, other than to suggest that this marriage of heaving Gothic style and brazenly modern storytelling is exactly the kind of aggressively fresh way of approaching horror that one hopes for from a pair of producers looking to make their mark in a generic landscape that's not looking to make room for them unless it is forced to do so. The film is still a bit kitschy and the low budget shows and the acting can be a bit stiff, but The City of the Dead honest-to-God shocked me, and I cannot remember the last time I had that reaction to something over half a century old, especially something in a mostly formulaic genre like Gothic horror. It's a complete delight in its spooky silliness, and I am officially outraged that it has no reputation to speak of beyond being the movie that happened before Amicus was a thing yet.