Australian Winter of Blood: Getting saltie

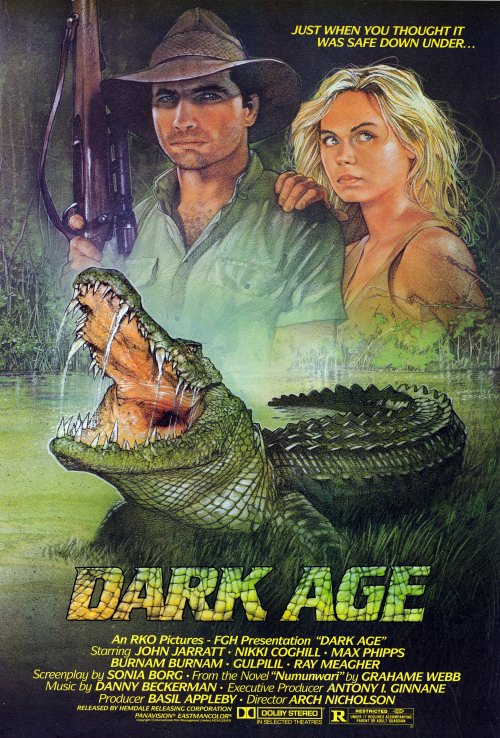

Of all the deadly animals on the Australian continent, none of them is more impressively terrifying than the massive saltwater crocodile, 20 feet of territorial ambush predator honed by nature to have the primordial look of some ancient devouring evil. And here we have what is, to the best of my knowledge, the earliest Australian film about a killer saltwater crocodile, Dark Age from 1987. This seems shockingly late to me, especially given that Dark Age is one of the most transparent Jaws knock-offs I have ever seen, and that particular genre cycle had more or less completely exhausted itself years earlier. But, as I mentioned in connection with 1984's Razorback, it seems that for whatever reason, the Australian horror film industry was slow to embrace the killer animal film, and never made a terribly large number of them.

More's the pity, if Razorback and Dark Age are any indication of the level of quality we could have expected from a more robust body of these films. In the particular case of Dark Age, though I have perhaps implied a certain shabbiness about it by calling it a transparent Jaws knock-off, I should hasten to clarify that what it does with the Jaws model is quite special, and it adopts its own distinct personality from very early on. The film borrows aspects of that 1975 masterpiece down to some unusually specific level of detail: anybody can play the "death of a child kicks us into the second act" card, or the "idiot hunters trying to capture the animal at night end up getting eaten" card, but this is something else: there's a conversation about the animal having craftily gone under the boat that's shortly followed by the animal tethered to the boat, playing a high-speed game of tug-of-war; a hunter who knows more than everybody else is introduced early on, but doesn't enter the plot in a significant way until halfway through. Hell, there's even a scene where two people argue about whether the extremely large animal that destroyed their high-strength fishing equipment was the monster, or some type of large fish. One feels that writers Sonia Borg, Tony Morphett, and Stephen Cross, adapting adapting Graham Webb's novel Numunwari, weren't so much copying Jaws as transcribing it.

And yet, Dark Age persists in feeling very much like its own thing, even in the most derivative scenes. The biggest reason for this is that, for all that the narrative has been scheduled out according to a formula, this is far more than just plugging a large, meat-eating, water-dwelling creature into predetermined beats. Dark Age takes the specifics of making its monster a saltwater crocodile very seriously, from several different angles, of which the most important is flagged for us right at the start of the movie, in a title crawl: these animals figure very highly in the mythology of numerous Australasian and Southeast Asian cultures. It's not clear specifically which Aboriginal Australian culture is meant to be involved in Dark Age - the two Aboriginal actors in the cast, Burnum Burnum (a leading Aboriginal activist) and David Gulpilil, are from two different nations in two different regions of Australia - but it's pretty clear that this is coming from the assumption that "Aboriginal" is one thing (the film's tone is very acutely part of the patronising "we have so much to learn from these Noble Savages and their greater connection to the ways of nature" mode that was all over Hollywood treatments of Native Americans around the same time - I'm not going to call this the Dances with Wolves of killer croc movies, but I'm not going to yell at anybody else for calling it that). Either way, it sets up a three-way conflict: the Aboriginal locals believe the arrival of an especially large and aggressive crocodile is nature's punishment for the whites killing off crocodile populations, and regardless, the animals should be protected and unmolested; the government officials want the thing caught and killed before it can ruin the region's tourism; and in between, ranger Steve Harris (John Jarratt) is eager to find and study this amazing creature while also removing it from the area.

Steve is our protagonist, of course, and thus we arrive at maybe the biggest of Dark Age's missteps: because he's a pretty bland stick in the mud. The human antagonist Besser (Max Phipps), an Ahab-like poacher who first just wants to kill the croc because he's an asshole, then because he's lost an arm to it, is a red-faced huffing-and-puffing ball of rage, but presented with a flair for local color; he's a cartoon baddie, but distinct. Oondabund (Burnum), the Quint figure who dispenses all of the film's exposition about traditional beliefs about salties, is a wry, deadpan comic figure, smarter than the rest of the cast combined and resigned to amusement that he's going to be ignored despite that. I know close to absolutely nothing about Burnum, but he's an absolutely delightful screen presence, bringing an upbeat, why-the-fuck-not attitude to even the most outwardly serious moments. He's not solely responsible for giving Dark Age a lighter tone than one might naturally expect of a movie that has a surprisingly explicit child death scene, but he's a big part of it, and every one of his scenes is a delight - bright and acerbic and pointed, all at once.

You know who's none of those things, is Jarratt: he's slightly pinched and humorless in every scene he doesn't share with Burnum (which is most of them in the first half), and not a whole lot more exciting after that. He's a square-jawed hero type in a movie that's much more wry and self-aware than that. It's hardly fatal - good characters are a bonus in a giant killer animal movie, not a requirement - but the film could be more than just a solid horror adventure, one feels at times, and his grounding presence is at least part of the reason it's not.

Still, best not to dwell on that, because it is a solid horror adventure. Very solid, even. Director Arch Nicholson has studied his Spielberg closely, and gets great mileage out of carefully rationing his shots of the movie's robot croc. It works just as well as hiding the shark in Jaws, and for the same reason: the prop isn't that great, but it starts to build up character and presence when all we can see are bits and pieces of its face, mostly its eyes. So by the time we see full body shots, we're already on the film's side, and willing to treat the clearly artificial nature of the beast as endearing, rather than distracting.

The film moves fast, covering all of the major Jaws plot beats in 91 minutes instead of 124, and adding an entire extra final act to address the fact that this movie has human villains and not just the implacable, hungry animal. But it never feels rushed, and there's even a stillness to the scenes that want to hammer home the mythic weight of the crocodile, rather than its destructive power. In turn, the scenes that do care more about death and destruction tend to be very punchy and quick cut. The pacing of the film in this way reflects the central thematic breakdown in the movie between white and Aboriginal conceptions of the crocodile, as something awe-inspiring in its terror versus horribly violent and savage.

All told, it's a pretty strong killer animal movie, certainly one of the best from the '80s, in any country - not a great decade for the genre, but it counts. There's a good amount of mystery in around the light adventurous tone, accentuated by Danny Beckerman's offbeat, sometimes playful and sometimes droning synth-heavy score; the cinematography by Andrew Lesnie (who would later shoot the cozy Babe and all of Peter Jackson's big-scale epics) oscillated between dappled woodland atmosphere and the hard sun of the inhuman landscape. It's a bit stiffly patronising in its earnest attempts to Say Something abut the tension between Aboriginal and white traditions, but it is at least very sincere about it. A wholly satisfying, better-than-expected genre film altogether, whose legacy is marred mostly by a strange accident of its distribution history: the distributor went bankrupt right before it was set to release, and it got tangled up in a legal mess, meaning that this especially fine example of Australian killer animal cinema was kept out of Australian theaters for 14 years. It's a terribly unjust fate for such a satisfying exemplar of a form that I would have though had been completely exhausted by 1987, but at least history has, to all appearances, corrected itself in the years since.

Body Count: 8 humans and 4 crocodiles.

More's the pity, if Razorback and Dark Age are any indication of the level of quality we could have expected from a more robust body of these films. In the particular case of Dark Age, though I have perhaps implied a certain shabbiness about it by calling it a transparent Jaws knock-off, I should hasten to clarify that what it does with the Jaws model is quite special, and it adopts its own distinct personality from very early on. The film borrows aspects of that 1975 masterpiece down to some unusually specific level of detail: anybody can play the "death of a child kicks us into the second act" card, or the "idiot hunters trying to capture the animal at night end up getting eaten" card, but this is something else: there's a conversation about the animal having craftily gone under the boat that's shortly followed by the animal tethered to the boat, playing a high-speed game of tug-of-war; a hunter who knows more than everybody else is introduced early on, but doesn't enter the plot in a significant way until halfway through. Hell, there's even a scene where two people argue about whether the extremely large animal that destroyed their high-strength fishing equipment was the monster, or some type of large fish. One feels that writers Sonia Borg, Tony Morphett, and Stephen Cross, adapting adapting Graham Webb's novel Numunwari, weren't so much copying Jaws as transcribing it.

And yet, Dark Age persists in feeling very much like its own thing, even in the most derivative scenes. The biggest reason for this is that, for all that the narrative has been scheduled out according to a formula, this is far more than just plugging a large, meat-eating, water-dwelling creature into predetermined beats. Dark Age takes the specifics of making its monster a saltwater crocodile very seriously, from several different angles, of which the most important is flagged for us right at the start of the movie, in a title crawl: these animals figure very highly in the mythology of numerous Australasian and Southeast Asian cultures. It's not clear specifically which Aboriginal Australian culture is meant to be involved in Dark Age - the two Aboriginal actors in the cast, Burnum Burnum (a leading Aboriginal activist) and David Gulpilil, are from two different nations in two different regions of Australia - but it's pretty clear that this is coming from the assumption that "Aboriginal" is one thing (the film's tone is very acutely part of the patronising "we have so much to learn from these Noble Savages and their greater connection to the ways of nature" mode that was all over Hollywood treatments of Native Americans around the same time - I'm not going to call this the Dances with Wolves of killer croc movies, but I'm not going to yell at anybody else for calling it that). Either way, it sets up a three-way conflict: the Aboriginal locals believe the arrival of an especially large and aggressive crocodile is nature's punishment for the whites killing off crocodile populations, and regardless, the animals should be protected and unmolested; the government officials want the thing caught and killed before it can ruin the region's tourism; and in between, ranger Steve Harris (John Jarratt) is eager to find and study this amazing creature while also removing it from the area.

Steve is our protagonist, of course, and thus we arrive at maybe the biggest of Dark Age's missteps: because he's a pretty bland stick in the mud. The human antagonist Besser (Max Phipps), an Ahab-like poacher who first just wants to kill the croc because he's an asshole, then because he's lost an arm to it, is a red-faced huffing-and-puffing ball of rage, but presented with a flair for local color; he's a cartoon baddie, but distinct. Oondabund (Burnum), the Quint figure who dispenses all of the film's exposition about traditional beliefs about salties, is a wry, deadpan comic figure, smarter than the rest of the cast combined and resigned to amusement that he's going to be ignored despite that. I know close to absolutely nothing about Burnum, but he's an absolutely delightful screen presence, bringing an upbeat, why-the-fuck-not attitude to even the most outwardly serious moments. He's not solely responsible for giving Dark Age a lighter tone than one might naturally expect of a movie that has a surprisingly explicit child death scene, but he's a big part of it, and every one of his scenes is a delight - bright and acerbic and pointed, all at once.

You know who's none of those things, is Jarratt: he's slightly pinched and humorless in every scene he doesn't share with Burnum (which is most of them in the first half), and not a whole lot more exciting after that. He's a square-jawed hero type in a movie that's much more wry and self-aware than that. It's hardly fatal - good characters are a bonus in a giant killer animal movie, not a requirement - but the film could be more than just a solid horror adventure, one feels at times, and his grounding presence is at least part of the reason it's not.

Still, best not to dwell on that, because it is a solid horror adventure. Very solid, even. Director Arch Nicholson has studied his Spielberg closely, and gets great mileage out of carefully rationing his shots of the movie's robot croc. It works just as well as hiding the shark in Jaws, and for the same reason: the prop isn't that great, but it starts to build up character and presence when all we can see are bits and pieces of its face, mostly its eyes. So by the time we see full body shots, we're already on the film's side, and willing to treat the clearly artificial nature of the beast as endearing, rather than distracting.

The film moves fast, covering all of the major Jaws plot beats in 91 minutes instead of 124, and adding an entire extra final act to address the fact that this movie has human villains and not just the implacable, hungry animal. But it never feels rushed, and there's even a stillness to the scenes that want to hammer home the mythic weight of the crocodile, rather than its destructive power. In turn, the scenes that do care more about death and destruction tend to be very punchy and quick cut. The pacing of the film in this way reflects the central thematic breakdown in the movie between white and Aboriginal conceptions of the crocodile, as something awe-inspiring in its terror versus horribly violent and savage.

All told, it's a pretty strong killer animal movie, certainly one of the best from the '80s, in any country - not a great decade for the genre, but it counts. There's a good amount of mystery in around the light adventurous tone, accentuated by Danny Beckerman's offbeat, sometimes playful and sometimes droning synth-heavy score; the cinematography by Andrew Lesnie (who would later shoot the cozy Babe and all of Peter Jackson's big-scale epics) oscillated between dappled woodland atmosphere and the hard sun of the inhuman landscape. It's a bit stiffly patronising in its earnest attempts to Say Something abut the tension between Aboriginal and white traditions, but it is at least very sincere about it. A wholly satisfying, better-than-expected genre film altogether, whose legacy is marred mostly by a strange accident of its distribution history: the distributor went bankrupt right before it was set to release, and it got tangled up in a legal mess, meaning that this especially fine example of Australian killer animal cinema was kept out of Australian theaters for 14 years. It's a terribly unjust fate for such a satisfying exemplar of a form that I would have though had been completely exhausted by 1987, but at least history has, to all appearances, corrected itself in the years since.

Body Count: 8 humans and 4 crocodiles.

Categories: adventure, here be monsters, horror, oz/kiwi cinema, summer of blood, thrillers