Australian Winter of Blood: God and the Devil couldn't have created a more despicable species

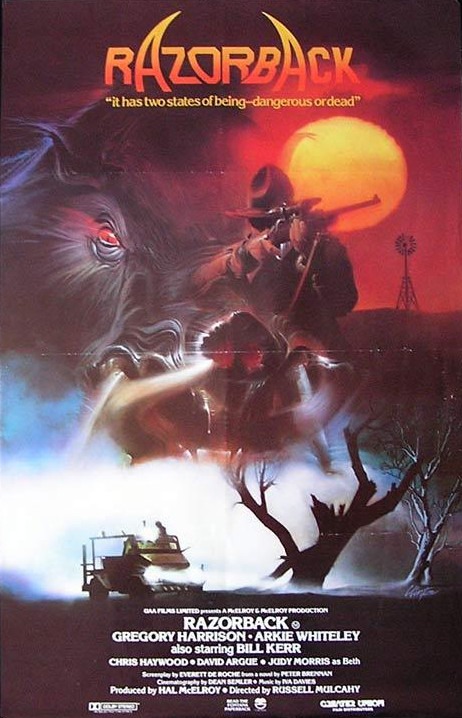

Given the incredible number of Australian animals that can kill a human in a variety of unpleasant ways, it's absolutely no surprise that there are horror films about such creatures. The only surprise is that there aren't more. As far as I can tell, the first killer animal film in the country's history was 1978's Long Weekend, a story of the wilderness taking revenge on some city assholes - an eco-horror film on the Frogs model for a post-Jaws world. As far as I can tell once again (though I am much less certain this time, the next Australian killer animal film, and the first to substantially borrow from the Jaws formula, didn't come out until six years later, in the form of 1984's Razorback - written by Everett De Roche, who also wrote Long Weekend, and several other significant early Australian horror films besides (this is no less than his third appearance in this Winter of Blood, following Patrick and Roadgames, something I was unaware of when I first assembled the schedule).

Razorback is a film about an impossibly large wild boar that eats people. It has virtually no interests outside of chasing that idea to its natural conclusion. Given the complexities of De Roche's earlier scripts, it would be easy to expect some layers here, but there's really not, and I think I admire the film for it. With nothing to distract it, it goes hard and fast for nothing but pure horror, and as a direct result has a degree of menacing atmosphere that is virtually unknown to the giant man-eating animal genre. The result is that it's less ridiculous than just about any of them; it's even a bit upsetting and bleak at times, and this is the mode it opens in. Somewhere in the Outback, grizzled old Jack Cullen (Bill Kerr) is at home watching his two-year-old grandson, when his house is torn apart by an enormous feral hog - Cullen barely glimpses it, but the damage it does admirably speaks to its size, as does the fact that it's able to race away with the boy like he ways nothing. One smash cut later, Cullen is standing trial for child murder, and everyone in the courtroom is openly mocking his anguished tale of a razorback the size of a small elephant. One smash cut later, the case has been dismissed for lack of evidence, and Cullen has the haunted look of a man with nothing left on his mind but killing.

One final smash cut takes us to New York, two years later, where television news reporter and animal rights activist Beth Winters (Judy Morris) is grimacing at her latest segment. She's ready to take some time off and spend her new pregnancy being relaxed, but she can't bring herself to pass up a hot tip about a pet food company in Australia illegally using kangaroos in its products. So off she goes for one last bit of work: her first step is to make everyone in the small town near the factory distrust her as some bleeding heart American; her second is to cross paths with Cullen, who doesn't care in the slightest about kangaroos, but says things about boars that suggest that he's been spending all of the last two years harboring Biblical wrath against boars. Stymied, she travels into the bush, where she catches a brief glimpse of something that looks boar-shaped but is much too big; subsequently two kangaroo-hunting psychos, Benny (Chris Haywood) and Dicko (David Argue) try to put a little scare into her, then try to sexually assault and possibly kill her, and only the nearby presence of a very large-sounding animal chases them off. Beth shuts herself in her car, but given that the boar that emerges from the gloom is larger than that car, it makes shot work of ripping the door off and dragging Beth away.

And now we arrive at our last new plot, the one that will take us the rest of the way through the film, as Beth's husband Carl (Gregory Harrison) travels to Australia to see if he can find what happened. He has enough presence of mind not to immediately announce himself as a crusading American, but all that means is that he gets himself on a hunting trip with Benny and Dicko, and as soon as it becomes clear that he doesn't have the stomach for their cruel methods, they leave him behind in the desert. Here, he manages to escape an attack by a group of feral pigs by hiding atop a windmill, and then crawls through the desert, hallucinating all the way, until he arrives at the remote home of Sarah Cameron (Arkie Whiteley), a friend of Cullen's who has been observing the increasing violence of the local feral pig populations with some alarm.

That gets us around halfway through the film, and it is by a considerable margin the better half. Once Carl and Cullen meet up, the film falls into the trap of many a horror film: it becomes less about the incomprehensible and mysterious, more of a series of action beats designed to contained the monster, both human and porcine. The Pet Pak canning facility, where most of the last act takes place, is an enjoyably over-the-top collection of conveyor belts, cherry red lighting, and open spaces filled with tumbling fog banks, but it's still a massive step down from the limitless vistas of the Outback. All in all, the film simply grows too domesticated as it winds towards the end, and the mere fact that we see a whole lot more of the very excellent animatronic razorback is a pretty limited compensation for how much the film's atmosphere collapses around this point.

The flipside, of course, is that the atmosphere up to this point is simply remarkable, enough to make this one of the strongest monster animal movies I have ever seen. That the first two victims are a two-year-old and a pregnant woman speaks to how much the makers of Razorback are willing to wallop us, and the first part of the movie wallops pretty damn hard indeed. A lot of this in some very large, excessive ways, though director Russell Mulcahy (making his first feature, and I daresay his best, after making quite a name for himself with his music videos) knows how to go small, as well: the use of medium close-ups during the trial scene in the beginning to carve Jake Cullen away from the rest of humanity gives the character lonely pathos alongside the expected anger and sorrow.

That being said, when the film goes big, it does so with great success. Mulcahy does terrific work in translating the stylistic logic of music videos into cinema, with a lot of fast cuts, bold colors, and a willingness to allow compositions to stand alone in their iconic grandeur without necessarily worrying if they fit together. And that goes for everything from shots of footprints in the sand to shot of the razorback's huge, hairy snout rising out of the darkness. This oughtn't work, but given how much the first hour already feels like a collection of striking narrative beats rather than a clear throughline (just consider how long it takes us to get a protagonist!), treating images as individual blasts of emotion and atmosphere fits with the overall flow.

Razorback also benefits from the cinematography of Dean Semler, who got the job on the strength of Mad Max 2, one of the best-looking films ever shot in Australia. All of his strengths are on admirably full display here, and if anything, Razorback goes even further in creating self-consciously mythic shots of the Outback landscapes, particularly during Carl's hallucinatory walk about, full of gorgeous sun-baked sand and severe blue skies, or robust sunsets. The shot of the horizon when Beth briefly sees the boar is a stunning field of hot, humid yellow slice by the dark red of the land; the night scenes with a heavy, rust-colored moon feel more primordial and dangerous than just about any other night in any other '80s horror film.

In short, the film looks like a nightmare, full of vivid, colorful, immaculately-composed images. And that nightmare feeling is exactly what it needs to sell its central conceit of giant killer boar. The razorback makes no sense, and all the characters know it; they simply have to deal with the fact that it exists anyway. This is nightmare narrative logic to a T, and having visuals that feel so unnatural and ethereal makes the presence of an impossible boar-monster feel like something perfectly natural given the impossibilities of the Australian wilderness and the inhumanity of that place even without silly movie monsters on top of it.

Body Count: 5 humans, 2 kangaroos, a couple of disembodied animals heads, and 1 giant boar.

Razorback is a film about an impossibly large wild boar that eats people. It has virtually no interests outside of chasing that idea to its natural conclusion. Given the complexities of De Roche's earlier scripts, it would be easy to expect some layers here, but there's really not, and I think I admire the film for it. With nothing to distract it, it goes hard and fast for nothing but pure horror, and as a direct result has a degree of menacing atmosphere that is virtually unknown to the giant man-eating animal genre. The result is that it's less ridiculous than just about any of them; it's even a bit upsetting and bleak at times, and this is the mode it opens in. Somewhere in the Outback, grizzled old Jack Cullen (Bill Kerr) is at home watching his two-year-old grandson, when his house is torn apart by an enormous feral hog - Cullen barely glimpses it, but the damage it does admirably speaks to its size, as does the fact that it's able to race away with the boy like he ways nothing. One smash cut later, Cullen is standing trial for child murder, and everyone in the courtroom is openly mocking his anguished tale of a razorback the size of a small elephant. One smash cut later, the case has been dismissed for lack of evidence, and Cullen has the haunted look of a man with nothing left on his mind but killing.

One final smash cut takes us to New York, two years later, where television news reporter and animal rights activist Beth Winters (Judy Morris) is grimacing at her latest segment. She's ready to take some time off and spend her new pregnancy being relaxed, but she can't bring herself to pass up a hot tip about a pet food company in Australia illegally using kangaroos in its products. So off she goes for one last bit of work: her first step is to make everyone in the small town near the factory distrust her as some bleeding heart American; her second is to cross paths with Cullen, who doesn't care in the slightest about kangaroos, but says things about boars that suggest that he's been spending all of the last two years harboring Biblical wrath against boars. Stymied, she travels into the bush, where she catches a brief glimpse of something that looks boar-shaped but is much too big; subsequently two kangaroo-hunting psychos, Benny (Chris Haywood) and Dicko (David Argue) try to put a little scare into her, then try to sexually assault and possibly kill her, and only the nearby presence of a very large-sounding animal chases them off. Beth shuts herself in her car, but given that the boar that emerges from the gloom is larger than that car, it makes shot work of ripping the door off and dragging Beth away.

And now we arrive at our last new plot, the one that will take us the rest of the way through the film, as Beth's husband Carl (Gregory Harrison) travels to Australia to see if he can find what happened. He has enough presence of mind not to immediately announce himself as a crusading American, but all that means is that he gets himself on a hunting trip with Benny and Dicko, and as soon as it becomes clear that he doesn't have the stomach for their cruel methods, they leave him behind in the desert. Here, he manages to escape an attack by a group of feral pigs by hiding atop a windmill, and then crawls through the desert, hallucinating all the way, until he arrives at the remote home of Sarah Cameron (Arkie Whiteley), a friend of Cullen's who has been observing the increasing violence of the local feral pig populations with some alarm.

That gets us around halfway through the film, and it is by a considerable margin the better half. Once Carl and Cullen meet up, the film falls into the trap of many a horror film: it becomes less about the incomprehensible and mysterious, more of a series of action beats designed to contained the monster, both human and porcine. The Pet Pak canning facility, where most of the last act takes place, is an enjoyably over-the-top collection of conveyor belts, cherry red lighting, and open spaces filled with tumbling fog banks, but it's still a massive step down from the limitless vistas of the Outback. All in all, the film simply grows too domesticated as it winds towards the end, and the mere fact that we see a whole lot more of the very excellent animatronic razorback is a pretty limited compensation for how much the film's atmosphere collapses around this point.

The flipside, of course, is that the atmosphere up to this point is simply remarkable, enough to make this one of the strongest monster animal movies I have ever seen. That the first two victims are a two-year-old and a pregnant woman speaks to how much the makers of Razorback are willing to wallop us, and the first part of the movie wallops pretty damn hard indeed. A lot of this in some very large, excessive ways, though director Russell Mulcahy (making his first feature, and I daresay his best, after making quite a name for himself with his music videos) knows how to go small, as well: the use of medium close-ups during the trial scene in the beginning to carve Jake Cullen away from the rest of humanity gives the character lonely pathos alongside the expected anger and sorrow.

That being said, when the film goes big, it does so with great success. Mulcahy does terrific work in translating the stylistic logic of music videos into cinema, with a lot of fast cuts, bold colors, and a willingness to allow compositions to stand alone in their iconic grandeur without necessarily worrying if they fit together. And that goes for everything from shots of footprints in the sand to shot of the razorback's huge, hairy snout rising out of the darkness. This oughtn't work, but given how much the first hour already feels like a collection of striking narrative beats rather than a clear throughline (just consider how long it takes us to get a protagonist!), treating images as individual blasts of emotion and atmosphere fits with the overall flow.

Razorback also benefits from the cinematography of Dean Semler, who got the job on the strength of Mad Max 2, one of the best-looking films ever shot in Australia. All of his strengths are on admirably full display here, and if anything, Razorback goes even further in creating self-consciously mythic shots of the Outback landscapes, particularly during Carl's hallucinatory walk about, full of gorgeous sun-baked sand and severe blue skies, or robust sunsets. The shot of the horizon when Beth briefly sees the boar is a stunning field of hot, humid yellow slice by the dark red of the land; the night scenes with a heavy, rust-colored moon feel more primordial and dangerous than just about any other night in any other '80s horror film.

In short, the film looks like a nightmare, full of vivid, colorful, immaculately-composed images. And that nightmare feeling is exactly what it needs to sell its central conceit of giant killer boar. The razorback makes no sense, and all the characters know it; they simply have to deal with the fact that it exists anyway. This is nightmare narrative logic to a T, and having visuals that feel so unnatural and ethereal makes the presence of an impossible boar-monster feel like something perfectly natural given the impossibilities of the Australian wilderness and the inhumanity of that place even without silly movie monsters on top of it.

Body Count: 5 humans, 2 kangaroos, a couple of disembodied animals heads, and 1 giant boar.