Sometimes there's a man... sometimes, there's a man

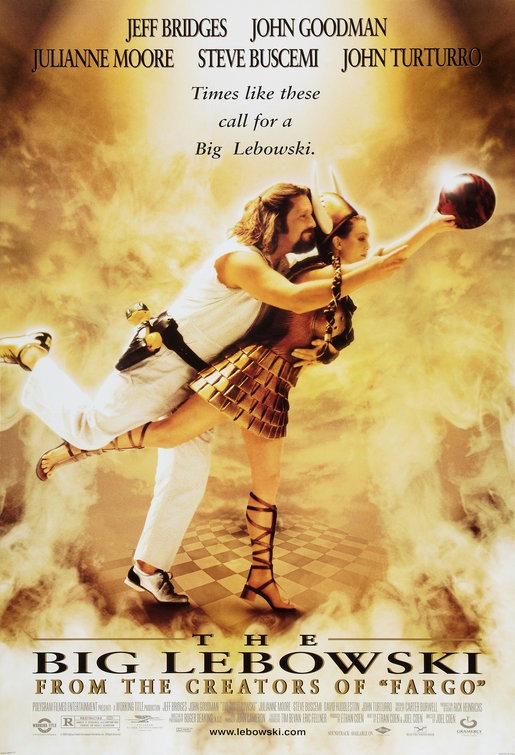

Joel & Ethan Coen have made a career-long habit of never repeating themselves two films in a row - maybe to keep themselves entertained, or looking to keep themselves from being pigeonholed, I don't know. Even so, there's nothing in their career that compares to how hard they switched things up after the great success of Fargo in 1996. The screenplay for The Big Lebowski screenplay predates that movie by several years - they were basically just waiting around for the cast they wanted to all be free at the same time, leading to the film's completion in time for a late 1997 release, though it ended up being held till spring of 1998 - so we can't go too far in saying that it was a deliberate palate-cleanser, but it comes awfully close to being the perfect anti-Fargo. Instead of a narrative coiling tighter and tighter around the characters, it has a nonsense story that nobody in the film seems to care about and even fewer understand; instead of a morality play of almost cosmic dimensions, it's an ambling hang-out movie built around an amiable stoner who's just a good guy because he doesn't have the energy to be anything else.

The trick to all the rest of the movie is that it's as precisely worked-out as any of the films the Coens made during the 1990s, an extraordinarily productive decade for them; but it looks like a shaggy, barely-assembled collection of random scenes that have nothing to do with the kidnapping mystery that purports to be the central spine of the film. The inspiration was the collected work of Raymond Chandler, one of the key crime fiction writers of the 1930s, '40s, and '50s, making this the second Coen film to draw from that time period of that genre, following their Dashiell Hammett homage with 1990's Miller's Crossing; but whereas that film played Hammett relatively straight - relatively - The Big Lebowski (whose is a nod to Chandler's 1939 novel The Big Sleep, one of his best-known works) has a lot more fun ripping Chandlerian motifs from the post-war world where they make the most sense and letting them look all goofy and lost in the early 1990s. Which is itself an oddly particular setting; I imagine that when the first draft was written, the Coens worked in enough references to the Gulf War of late 1990 and early 1991 that they didn't want to have to pull them out.

There aren't even that many references, but the specificity suits the film well, giving it a slight hint of not existing properly in time that goes even beyond the filmmaker's notorious decision to pretend that Fargo was based on real events that had taken place in 1987. It is, in a sense, a very grounded film: it has more socio-political context than any other Coen film, being a very deliberate "what happened after the death of the hippie movment" story; it also has perhaps the most realistic cinematography of any of the films Roger Deakins shot for the directors, making extensive use of the scuzzy amber haze provided by sodium vapor lighting in a big city. But then on the other hand, the whole thing is introduced as a florid tale of the American West, introduced with tongue firmly in cheek as a tumblweed blows across the desert scrub and right into Los Angeles, ending in the Pacific Ocean, while the Sons of the Pioneers sing "Tumbling Tumbleweeds" on the soundtrack, while Sam Elliott - a man whose gravel-saturated voice would suggest a desiccated old cowboy in pretty much any context - narrating us into the setting with such a folksy aw-shucks attitude that he ends up losing his place amidst all the colorful language. And his later physical appearance within the movie just adds to the feeling of artificiality. So it's... a realist fable? Doesn't matter, which is the joke - one of the things that will define The Big Lebowski is that, for all the different things we can bring in to try to contextualise it (cowboy songs, Raymond Chandler, the Coens' own career), it ultimately just plays like a shapeless grab bag of absurd notions, unified only in that they all happen to the same hapless layabout, Jeffrey "The Dude" Lebowski (Jeff Bridges, in my favorite performance of his very impressive career).

It plays like it's shapeless, which is a very different thing than being shapeless, though the shape The Big Lebowski takes is somewhat hard to pin down. One of the things that always makes the film stand out to me as an oddity in the Coens' career is the way it uses dialogue. Starting as early as their second film, 1987's Raising Arizona (like Lebowski, one of their handful of out-and-out comedies), one of their major stylistic trademarks is to stamp each one of their films with an extremely specific dialect. The chirpy sing-song of the upper Midwest in Fargo is the most obvious example, but there's also the drawling wordiness of Raising Arizona or the dense jungle of slang in Miller's Crossing, and there would be several more exercises of this sort still to come. In The Big Lebowski, almost all the characters speak in highly distinctive ways, but they all speak differently (the Coens played with this in Barton Fink, but they didn't go nearly this far with it. The actual "big" Lebowski (David Huddleston) who hires the Dude as the ineffectual private eye to find his missing wife, Bunny (Tara Reid), has a loud speaking manner and a tendency towards big words that make him feel stuffy and stentorian; his personal assistant Brandt (Philip Seymour Hoffman) has a prim rhythm that's posh in a very different way. The feminist outsider artist Maude Lebowski (Julianne Moore), the big Lebowski's estranged daughter, speaks her sentences very quickly and then clips them off, while using an approximation of a Mid-Atlantic accent that feels posh in yet a third way. Walter Sobchak (John Goodman), a bellowing Vietnam vet with a huge chip on his shoulder, gets lots of curt lines to shout, but he's also done the work of adopting a particular kind of Southern California accent that nobody else in the movie uses (it's most audible in his very tight, close "oo" sounds - he generally calls the main character "Dewd" rather than "Dood"). Steve Buscemi, as the Dude and Walter's idiot friend Donny, gets to replace the nasal snarling of his Fargo killer with a sweetly lilting series of short questions, the most uncharacteristically boyish deliveries of his whole career. And that's not even getting to the full-on cartoon characters, like Elliott, or John Turturro's psychotic Jesus Quintana, or Peter Stormare's shticky German nihilist.

At the center of this, Bridges basically just speaks like himself, a regular Californian. The cunning thing the Coens do with him, then, is not to play with dialect comedy, but with vocabulary: the Dude's speaking tic is that he starts to adopts words and whole phrases that other people use in front of him. And this, to go all the way back to the start of the last paragraph, is one way that the film structures itself: through the accretion of dialogue patterns. It's not just in the Dude's speeches that we hear lines repeating themselves, though since he gets by far the most screentime, he's the person where it's most obvious. There are several examples of words and phrases connecting disparate parts of this apparently formless movie, slightly tightening it together into a loose network. One of the things the Coens specifically borrowed from Chandler was his books' sense of Los Angeles as a kind of organic entity, moving from neighborhood to neighborhood and up and down the class hierarchy; language does that here in addition to the movement of the plot. And so does Bridges's performance as the Dude, just sufficiently out-of-focus at any given moment that he always seems slightly out of place no matter where he is; so when he feels out-of-focus in every new location, no matter how different the aesthetic universes of those locations, it always feels like they have something in common.

As to those different aesthetic universes: much as with the dialogue, the film uses a polyglot of visual styles. Deakins can always fall back on the realism as a baseline, but even that has some inflection: the interior of the bowling alley where the Dude, Walter, and Donny spend their happiest hours is a bit softer than the fluorescent harshness of a truly realistic bowling alley would ever look, and the Dude's apartment has a filtered, dusky grunginess that's different than the filthy muddle of the sodium vapor night. Meanwhile, other locations are all marked out visually, sometimes by subtle changes: the big Lebowski's mansion is basically just natural lighting and naturally-motivated lighting, but it has a higher contrast, making it feel sunnier, than the other daytime exteriors in the film. Maude's studio is underlit with smooth, soft blacks that are both moodier and cleaner than any other dark location in a film that does, after all, borrow some cues from film noir, though never in a very systematic way.

And all of these contrast with the way that the film shoots its fantasy sequences: there are two of these, and they are both crisp and sharp, the latter in particular - which also doubles as the first musical number in a Coen film, a sort of low-budget homage to MGM musicals of the '30s whose smooth, shadow-free locations are incongruously kicked off by a playful riff on German Expressionism, as the Dude dances with his own gigantic shadow in a starkly-lit grey doorway. This is the same general approach used by the film's strangest sequence of all - no, the MGM musical pastiche (that's also a non-sexual parody of pornographic films) - isn't its strangest sequence - when the Dude's wanderings take him to a Malibu beach party that's also staged like a sex cult ritual from out of some deranged European art film: a slow motion shot of a topless woman falling through space against a jet-black night sky, followed by a sharp shot of one of her male admirers, bathed in high-contrast orange lighting, is enough to pull this sequence even further into the realm of dream imagery than its actual dream sequences.

That's all a whole lot of different approaches, and the film doesn't even feint towards trying to tie them together. That's part of the joke, that they don't fit together, that the whole world is jerry-rigged out of a hundred disparate parts, and the Dude is so extremely laid back and unfussed that he can simply float from one part to the next without trouble. The mystery plot is basically a giant shrug stretched out as long as possible - not something unknown to '40s mystery writers, nor Chandler specifically, though it's unusual to see it played entirely for comedy - so having the film's aesthetic feel cobbled together from nothing but the Dude's obliviousness is pretty much exactly the right fit.

The Big Lebowski isn't as weightless as I'm probably making it out to be. There's an undercurrent of melancholy stretching from the big Lebowski's insults about the failure of the hippie movements to the Dude's recitation of his great moments as an activist in the '60s in a stoned croak; there's a sense that the Dude has failed. Only Elliott's opening and closing monologues really do much to suggest something else; but of course, those are the moments the film chooses to begin and end with, so they have more emphasis.

Even without recourse to pop sociology, The Big Lebowski isn't an entirely lighthearted romp. This is the first Coen film with a soundtrack made up primarily of pre-existing music, curated for the occasion by T-Bone Burnett (regular Coen composer Carter Burwell provided a couple of cues, but they are not significantly foregrounded), and they tend towards the mordant or jarring: a frantic cover of "Hotel California" by Gipsy Kings; Creedence Clearwater Revival's scorching Vietnam anthem "Run Through the Jungle"; Kenny Rogers & the First Edition's "Just Dropped In", here given an almost apocalyptic mood in concert with the visuals; Townes Van Zandt's vocally strained cover of "Dead Flowers", which takes over the final scene with a wistful melancholy. The three most upbeat songs on the soundtrack are all subverted: "Viva Las Vegas" is used in a scene clarifying some details about the vapid Bunny, Creedence's "Lookin' Out My Back Door" is cut off by a car crash, and the Eagles' "Peaceful Easy Feeling" is subjected to the Dude's dismissive "I fuckin' hate the Eagles", for which he is literally thrown to the curb. Which is all to say, the music places just a little hint of sadness into the movie, in a way that can't quite be pinpointed and is contrasted with the Dude's own easygoing vibe - but it's there.

Of course, first and foremost, this is a comedy, and it's a superb one; among the funniest movies of the '90s, for a start. This is in no small part thanks to how excessively good every last member of the cast is, from Goodman's scene-stealing belligerence that keeps twisting into self-assured, calm logic, to Moore's outstandingly alien line readings (in a film with no end of great dialogue, her reading of "The word itself makes some men uncomfortable. Vagina.", with an impeccably-timed beat between the sentences, strikes me as undervalued), and on, and on. It would be even easier to turn this into a list of my favorite nuggets of acting than my favorite lines of dialogue, so I'll cut myself off, but only after mentioning the way that Hoffman freezes a giant toothy grin onto his face and gets his entire body below his neck to start convulsing in embarrassment is one of my favorite moments in that genius actor's entire career, and the first time that I ever thought to myself that were is a performer well worth paying attention to, going forward.

And as always, the comedy largely centers itself on Bridges, whose blissfully nonplussed reaction shots, well-crafted in by the Coens and Tricia Cooke in the editing room, always provide a grounding effect for the rest of the movie. It's a big outlandish cartoon, going in every which direction, but his loose, limber attitude also give is plenty of simple character-based humor, while providing contrast to the formal precision around him.

The casual shagginess that Bridges gives the film almost ends up being too much, and I won't argue that The Big Lebowski wouldn't benefit from a little bit more tightening up. Did it really need two entirely distinct opening montages? Does every single one of those shaggy asides actually work (I would, at a minimum, think about dropping the performance piece by the Dude's landlord, played by Jack Kehler)? Is there a reason why this amiable, scrappy comedy was also, by however slender a margin, the Coens' longest film up to that point (and still, 22 years later, their third-longest, behind The Ballad of Buster Scruggs and No Country for Old Men)? But then again, these are stupid questions: the movie is all about non-judgmentally, blissfully sidling through life and letting things be as it may, and a movie that was as impeccably-made as Miller's Crossing or Fargo would almost certainly not be able to tap into that vibe so warmly and to such routinely hilarious effect. Sometimes, it's the imperfections that make something interesting, and the battered, weathered Dude is a splendid example of just that.

The trick to all the rest of the movie is that it's as precisely worked-out as any of the films the Coens made during the 1990s, an extraordinarily productive decade for them; but it looks like a shaggy, barely-assembled collection of random scenes that have nothing to do with the kidnapping mystery that purports to be the central spine of the film. The inspiration was the collected work of Raymond Chandler, one of the key crime fiction writers of the 1930s, '40s, and '50s, making this the second Coen film to draw from that time period of that genre, following their Dashiell Hammett homage with 1990's Miller's Crossing; but whereas that film played Hammett relatively straight - relatively - The Big Lebowski (whose is a nod to Chandler's 1939 novel The Big Sleep, one of his best-known works) has a lot more fun ripping Chandlerian motifs from the post-war world where they make the most sense and letting them look all goofy and lost in the early 1990s. Which is itself an oddly particular setting; I imagine that when the first draft was written, the Coens worked in enough references to the Gulf War of late 1990 and early 1991 that they didn't want to have to pull them out.

There aren't even that many references, but the specificity suits the film well, giving it a slight hint of not existing properly in time that goes even beyond the filmmaker's notorious decision to pretend that Fargo was based on real events that had taken place in 1987. It is, in a sense, a very grounded film: it has more socio-political context than any other Coen film, being a very deliberate "what happened after the death of the hippie movment" story; it also has perhaps the most realistic cinematography of any of the films Roger Deakins shot for the directors, making extensive use of the scuzzy amber haze provided by sodium vapor lighting in a big city. But then on the other hand, the whole thing is introduced as a florid tale of the American West, introduced with tongue firmly in cheek as a tumblweed blows across the desert scrub and right into Los Angeles, ending in the Pacific Ocean, while the Sons of the Pioneers sing "Tumbling Tumbleweeds" on the soundtrack, while Sam Elliott - a man whose gravel-saturated voice would suggest a desiccated old cowboy in pretty much any context - narrating us into the setting with such a folksy aw-shucks attitude that he ends up losing his place amidst all the colorful language. And his later physical appearance within the movie just adds to the feeling of artificiality. So it's... a realist fable? Doesn't matter, which is the joke - one of the things that will define The Big Lebowski is that, for all the different things we can bring in to try to contextualise it (cowboy songs, Raymond Chandler, the Coens' own career), it ultimately just plays like a shapeless grab bag of absurd notions, unified only in that they all happen to the same hapless layabout, Jeffrey "The Dude" Lebowski (Jeff Bridges, in my favorite performance of his very impressive career).

It plays like it's shapeless, which is a very different thing than being shapeless, though the shape The Big Lebowski takes is somewhat hard to pin down. One of the things that always makes the film stand out to me as an oddity in the Coens' career is the way it uses dialogue. Starting as early as their second film, 1987's Raising Arizona (like Lebowski, one of their handful of out-and-out comedies), one of their major stylistic trademarks is to stamp each one of their films with an extremely specific dialect. The chirpy sing-song of the upper Midwest in Fargo is the most obvious example, but there's also the drawling wordiness of Raising Arizona or the dense jungle of slang in Miller's Crossing, and there would be several more exercises of this sort still to come. In The Big Lebowski, almost all the characters speak in highly distinctive ways, but they all speak differently (the Coens played with this in Barton Fink, but they didn't go nearly this far with it. The actual "big" Lebowski (David Huddleston) who hires the Dude as the ineffectual private eye to find his missing wife, Bunny (Tara Reid), has a loud speaking manner and a tendency towards big words that make him feel stuffy and stentorian; his personal assistant Brandt (Philip Seymour Hoffman) has a prim rhythm that's posh in a very different way. The feminist outsider artist Maude Lebowski (Julianne Moore), the big Lebowski's estranged daughter, speaks her sentences very quickly and then clips them off, while using an approximation of a Mid-Atlantic accent that feels posh in yet a third way. Walter Sobchak (John Goodman), a bellowing Vietnam vet with a huge chip on his shoulder, gets lots of curt lines to shout, but he's also done the work of adopting a particular kind of Southern California accent that nobody else in the movie uses (it's most audible in his very tight, close "oo" sounds - he generally calls the main character "Dewd" rather than "Dood"). Steve Buscemi, as the Dude and Walter's idiot friend Donny, gets to replace the nasal snarling of his Fargo killer with a sweetly lilting series of short questions, the most uncharacteristically boyish deliveries of his whole career. And that's not even getting to the full-on cartoon characters, like Elliott, or John Turturro's psychotic Jesus Quintana, or Peter Stormare's shticky German nihilist.

At the center of this, Bridges basically just speaks like himself, a regular Californian. The cunning thing the Coens do with him, then, is not to play with dialect comedy, but with vocabulary: the Dude's speaking tic is that he starts to adopts words and whole phrases that other people use in front of him. And this, to go all the way back to the start of the last paragraph, is one way that the film structures itself: through the accretion of dialogue patterns. It's not just in the Dude's speeches that we hear lines repeating themselves, though since he gets by far the most screentime, he's the person where it's most obvious. There are several examples of words and phrases connecting disparate parts of this apparently formless movie, slightly tightening it together into a loose network. One of the things the Coens specifically borrowed from Chandler was his books' sense of Los Angeles as a kind of organic entity, moving from neighborhood to neighborhood and up and down the class hierarchy; language does that here in addition to the movement of the plot. And so does Bridges's performance as the Dude, just sufficiently out-of-focus at any given moment that he always seems slightly out of place no matter where he is; so when he feels out-of-focus in every new location, no matter how different the aesthetic universes of those locations, it always feels like they have something in common.

As to those different aesthetic universes: much as with the dialogue, the film uses a polyglot of visual styles. Deakins can always fall back on the realism as a baseline, but even that has some inflection: the interior of the bowling alley where the Dude, Walter, and Donny spend their happiest hours is a bit softer than the fluorescent harshness of a truly realistic bowling alley would ever look, and the Dude's apartment has a filtered, dusky grunginess that's different than the filthy muddle of the sodium vapor night. Meanwhile, other locations are all marked out visually, sometimes by subtle changes: the big Lebowski's mansion is basically just natural lighting and naturally-motivated lighting, but it has a higher contrast, making it feel sunnier, than the other daytime exteriors in the film. Maude's studio is underlit with smooth, soft blacks that are both moodier and cleaner than any other dark location in a film that does, after all, borrow some cues from film noir, though never in a very systematic way.

And all of these contrast with the way that the film shoots its fantasy sequences: there are two of these, and they are both crisp and sharp, the latter in particular - which also doubles as the first musical number in a Coen film, a sort of low-budget homage to MGM musicals of the '30s whose smooth, shadow-free locations are incongruously kicked off by a playful riff on German Expressionism, as the Dude dances with his own gigantic shadow in a starkly-lit grey doorway. This is the same general approach used by the film's strangest sequence of all - no, the MGM musical pastiche (that's also a non-sexual parody of pornographic films) - isn't its strangest sequence - when the Dude's wanderings take him to a Malibu beach party that's also staged like a sex cult ritual from out of some deranged European art film: a slow motion shot of a topless woman falling through space against a jet-black night sky, followed by a sharp shot of one of her male admirers, bathed in high-contrast orange lighting, is enough to pull this sequence even further into the realm of dream imagery than its actual dream sequences.

That's all a whole lot of different approaches, and the film doesn't even feint towards trying to tie them together. That's part of the joke, that they don't fit together, that the whole world is jerry-rigged out of a hundred disparate parts, and the Dude is so extremely laid back and unfussed that he can simply float from one part to the next without trouble. The mystery plot is basically a giant shrug stretched out as long as possible - not something unknown to '40s mystery writers, nor Chandler specifically, though it's unusual to see it played entirely for comedy - so having the film's aesthetic feel cobbled together from nothing but the Dude's obliviousness is pretty much exactly the right fit.

The Big Lebowski isn't as weightless as I'm probably making it out to be. There's an undercurrent of melancholy stretching from the big Lebowski's insults about the failure of the hippie movements to the Dude's recitation of his great moments as an activist in the '60s in a stoned croak; there's a sense that the Dude has failed. Only Elliott's opening and closing monologues really do much to suggest something else; but of course, those are the moments the film chooses to begin and end with, so they have more emphasis.

Even without recourse to pop sociology, The Big Lebowski isn't an entirely lighthearted romp. This is the first Coen film with a soundtrack made up primarily of pre-existing music, curated for the occasion by T-Bone Burnett (regular Coen composer Carter Burwell provided a couple of cues, but they are not significantly foregrounded), and they tend towards the mordant or jarring: a frantic cover of "Hotel California" by Gipsy Kings; Creedence Clearwater Revival's scorching Vietnam anthem "Run Through the Jungle"; Kenny Rogers & the First Edition's "Just Dropped In", here given an almost apocalyptic mood in concert with the visuals; Townes Van Zandt's vocally strained cover of "Dead Flowers", which takes over the final scene with a wistful melancholy. The three most upbeat songs on the soundtrack are all subverted: "Viva Las Vegas" is used in a scene clarifying some details about the vapid Bunny, Creedence's "Lookin' Out My Back Door" is cut off by a car crash, and the Eagles' "Peaceful Easy Feeling" is subjected to the Dude's dismissive "I fuckin' hate the Eagles", for which he is literally thrown to the curb. Which is all to say, the music places just a little hint of sadness into the movie, in a way that can't quite be pinpointed and is contrasted with the Dude's own easygoing vibe - but it's there.

Of course, first and foremost, this is a comedy, and it's a superb one; among the funniest movies of the '90s, for a start. This is in no small part thanks to how excessively good every last member of the cast is, from Goodman's scene-stealing belligerence that keeps twisting into self-assured, calm logic, to Moore's outstandingly alien line readings (in a film with no end of great dialogue, her reading of "The word itself makes some men uncomfortable. Vagina.", with an impeccably-timed beat between the sentences, strikes me as undervalued), and on, and on. It would be even easier to turn this into a list of my favorite nuggets of acting than my favorite lines of dialogue, so I'll cut myself off, but only after mentioning the way that Hoffman freezes a giant toothy grin onto his face and gets his entire body below his neck to start convulsing in embarrassment is one of my favorite moments in that genius actor's entire career, and the first time that I ever thought to myself that were is a performer well worth paying attention to, going forward.

And as always, the comedy largely centers itself on Bridges, whose blissfully nonplussed reaction shots, well-crafted in by the Coens and Tricia Cooke in the editing room, always provide a grounding effect for the rest of the movie. It's a big outlandish cartoon, going in every which direction, but his loose, limber attitude also give is plenty of simple character-based humor, while providing contrast to the formal precision around him.

The casual shagginess that Bridges gives the film almost ends up being too much, and I won't argue that The Big Lebowski wouldn't benefit from a little bit more tightening up. Did it really need two entirely distinct opening montages? Does every single one of those shaggy asides actually work (I would, at a minimum, think about dropping the performance piece by the Dude's landlord, played by Jack Kehler)? Is there a reason why this amiable, scrappy comedy was also, by however slender a margin, the Coens' longest film up to that point (and still, 22 years later, their third-longest, behind The Ballad of Buster Scruggs and No Country for Old Men)? But then again, these are stupid questions: the movie is all about non-judgmentally, blissfully sidling through life and letting things be as it may, and a movie that was as impeccably-made as Miller's Crossing or Fargo would almost certainly not be able to tap into that vibe so warmly and to such routinely hilarious effect. Sometimes, it's the imperfections that make something interesting, and the battered, weathered Dude is a splendid example of just that.

Categories: comedies, crime pictures, indies and pseudo-indies, mysteries, the coen brothers