I guess we all have that Barton Fink feeling. But since you're Barton Fink, I'm assuming you have it in spades.

If there's a key to cracking Barton Fink, and honestly I'm pretty sure that there isn't, it might be the simplest bit of production trivia of all. The 1991 film, the fourth written and directed by Joel & Ethan Coen, was written in a brief burst of activity when they were stuck on the labyrinthine script for Miller's Crossing, their third. To work out a bad case of writer's block, the brothers wrote a fable about a man with writer's block. And maybe there really doesn't need to be any more to it than that. Maybe the whole thing is just an elaborate joke with a single, lame punchline: "writer's block is hell".

That certainly isn't the most outlandish reading I can think of for a movie with a calculated indifference to yielding up meaning. I mean, on the one hand, it's quite straightforward: Barton Fink (John Turturro), a fairly new playwright in 1941, is convinced that he's on the brink of telling a great new story about the American working class, one that will revolutionise American theatre; he is, however a hypocrite and dilettante whose interest in the working class is strictly aesthetic and whose high-minded progressive ideals are mostly about declaring his virtue publicly and thereby impressing his high-minded progressive peers, and who blatantly does not care about the actual working class as it is constituted of individual people, but only as an ideal he has constructed. A message with absolutely no application to our own times, obviously. The Coens have a great deal of fun mocking him - he is the most obnoxious protagonist in any Coen film, maybe even the only one who's genuinely unlikable - by shipping him off to Hollywood, where his extremely self-important awareness of his writing skills proves incapable of the laughably uncomplicated task of writing a formulaic B-picture about wrestlers, a perfectly everyday genre that this self-anointed poet of the masses has apparently never heard of.

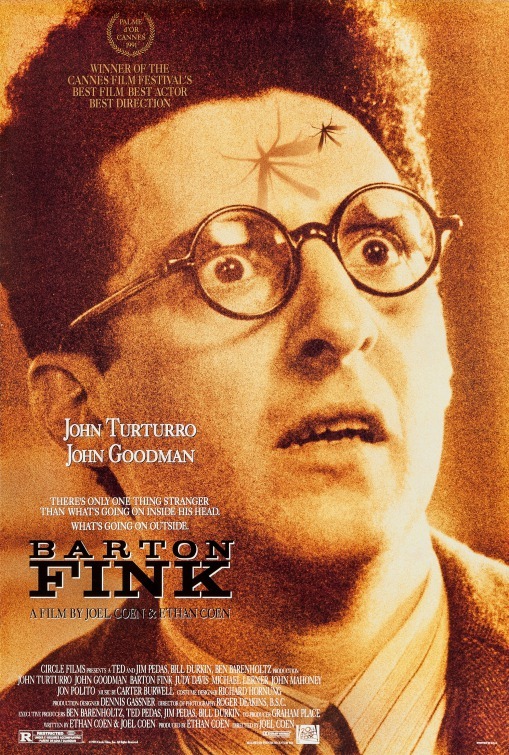

If that's all there was to it - poking fun at the fecklessness of an elite intellectual class so worked up waxing rhapsodic about their ideals that they completely forget to live them - I imagine Barton Fink would still be an enjoyably caustic time. But it's so much more. It's one of the greatest American films of the 1990s, a film that swept the awards at the Cannes International Film Festival so hard (Picture, Director, Actor) that they changed the rules to make sure no film could ever do it again, and still, after all these years and movies, probably the most inexhaustible film the Coens have ever made. For one thing, it's a puzzle, though a puzzle that the Coens have more or less stated outright doesn't have a solution. The film is heavy with symbolism, far more symbolism than any one of their films would possess again, and a lot of it seems frankly inscrutable. Not all of it - some of it is extremely obvious, in fact (the biggest one being that Hotel Earle, where Barton is staying during his trip to Los Angeles, is indicated to be the actual, literal Hell). And some of it seems to obvious in an intuitive way that keeps eluding you when you try to put it into words, like the shot of a seabird plunging into the ocean in the last shot, that the Coens have sworn consistently over the years was a happy accident.

My gut feeling, based more on the rest of the Coens' work than anything Barton Fink directly presents, is that this is a trap. With very few exceptions, these are screenwriters whose favorite mode is one of arch irony, and the ironic take on the film's symbolism goes back to the idea of writer's block. And maybe this is my own bias talking as well, but doesn't it sometimes feel like symbolism is the refuge of a writer who has no ideas and is trying to make them seem fancier by making them opaque? Especially in the case of the mid-century literature of the middlebrow intelligentsia who seem to regard Barton as a great writer - and if I can chase an idea for a moment (but this is a film that encourages dropping what you're doing and running after ideas - it feels deliberately shaggy and meandering after the impeccable mechanics of Miller's Crossing), whether or not he has actual talent is one of the film's great mysteries. The way the film stages his revelations in the second half, when he's finally unblocked, suggests that he's channeling something powerful and divine; but this is immediately undercut with the blunt joke that his big inspiration has been to rip-off his own work, word-for-word. The fatuous praise of middlebrow airheads in the beginning and the anti-intellectual dismissal of a crude studio head in the end both seem to be be neutral evidence at best. I like to imagine that his screenplay is no good, at any rate; the idea that he has made a Faustian pact with the devil (which I think is one of the more obvious bits of symbolism that we can cling to), just to write a mediocre, cliché-ridden bit of midcentury social realism - and not even have the self-awareness to realise it! - feels like an appropriately bitter punchline for the filmmakers who, many years and career twists and turns from this point, would be responsible for Burn After Reading and A Serious Man.

But I was speaking of symbolism, and middlebrow writers relying on it as a crutch to get through writer's block, and part of me can't help but wonder: is that the joke? Especially given that the directors seem to regard their own symbolism as a dead end? Or maybe the joke is on Barton's apparent commitment to the idea that art must be didactic to be meaningful, that everything has to be spelled out and buttoned up. Of the final four sentences that Barton speaks, two of them are "I don't know", and there's no way that's an accident - an author who can't explain anything serving as the final punctuation mark for a couple of authors who won't explain anything.

But perhaps even treating this as a metanarrative joke about writer's block and the Coens' mildly self-negating attitude towards writers who think that they're too good for simply, honest genre mechanics - Barton Fink is one of the most generically slippery movies I can name, and a uniquely impenetrable art film by American standards - perhaps even this goes too far in a movie that feels open to any interpretation as long as we agree that they're all equally wrong. If we go all the way down, maybe the meaning of the film is flagged in a line that, unusually for this film, does jump and down screaming that we notice how immaculately well-built and quippy it is. Audrey Taylor (Judy Davis), the beleagued muse, handmaid, and nanny to a dysfunctional alcoholic former genius writer, and has come over to help Barton crack the mystery of how to write a boilerplate wrestling picture. "Usually, they're... simply morality tales", she says, explaining the basics of Hollywood conflict-building with patronising patience. And perhaps Barton Fink is simply a morality tale, too, though not a simple one, if the distinction makes sense. I hold it to be self-evident that the Coens' filmography broadly breaks into two parts, before and after a three-year gap between 2004's The Ladykillers and 2007's No Country for Old Men, and the difference isn't simply that they were starting to lose their way and then found it. After 2007, their entire filmography, even in the comedies, becomes obsessed with questions of moral behavior in an amoral universe, something that only occasionally shows up in their first run of movies. Morality is a factor in these films, especially 1996's Fargo and 2001's The Man Who Wasn't There, but they're all much more unified by being misadventures about people who think they're more capable than they are getting trapped in a convoluted web of their own creation. Barton Fink has a bit of that - Barton assumes he can sweep out to Los Angeles, bash out a few perfect screenplays, and head back to New York a much richer man - but it's not at all the focus. This is the one film of that first phase of their career that feels like it belongs in the second phase, a grandiose cosmic story about ethics and living with the sins you have committed, already condemned to Hell with no way out. Barton's sins include hypocritically jetting out to Hollywood for money, thinking too highly of his own ability to change the world, looking down on movies that want to be well-built and unpretentious entertainment, and superciliously ignoring Charlie Meadows (John Goodman), the ebullient, eager-to-please salesman who lives in the room next door at the Earle, preferring to talk at him rather than engage him as a fellow human, and that these are what the Coens choose to send him to Hell for speaks to their moral worldview rather cleanly, I think.

What you might not guess from all of that is that Barton Fink is a delight to watch. This is the film where the Coens figured out the knack for comedy that would follow them the rest of their career: 1984's Blood Simple isn't very funny at all, and 1987's Raising Arizona is a big silly farce, and Miller's Crossing is very "clever" but not really "funny". Barton Fink hits the sweet spot that the brothers would keep hitting thereafter: a sharp, barking, absurdist sense of humor that intertwines with the heavy weight of the story so intimately that it's often impossible to tell if we're watching a particularly morbid dark comedy, or a particularly hilarious tragedy. Barton Fink is clearly not "a comedy", though it's often funny as hell. Transparently so, in its tour of Hollywood venality, embodied by the giddy performance of Michael Lerner as Jack Lipnick, the force of pure will who runs the studio that Barton has gotten a contract with. It's a sublime marriage of performer and part, resulting in line after line of breathtaking screwball banter, charged with a perfect level of toxic indifference masked by bonhomie. It's not the only great purely comic performance: Tony Shalhoub's gravelly producer and John Mahoney's vulgar drunk author are both pitched exactly where they need to be as well, while Davis and Jon Polito are both funny and deeply melancholy as toadies with a broken sense of their own self worth.

But the highlight, both of acting, and of getting at the Coens' brilliant new comic sensibility, is surely Goodman, whose performance as Charlie is in the running for the best acting in any Coen film. Part of the film's very strange comic strategy is to sharply contrast the fast-moving dialogue and brightly-lit spaces of L.A. with the slow, dusky interiors of the Hotel Earle, and Goodman's performance is the anchor to that space (along with a glorious small role for Steve Buscemi as the inhumanly upbeat bellhop Chet). The film slows down incredibly inside the hotel, lingering on the droning rhythm of a bad air conditioning system deep in the sound mix (augmented by composer Carter Burwell's extremely sparing use of fragments of bass music - this is one of the two least-musical of all Coen films, but it uses its score with unmatched precision), and other sound effects plucked very deliberately to ride atop the mix, creating a space that feels constructed one piece at a time. That vibe carries over on to the editing (the Coens cut this film themselves, with Michael Berenbaum and Tricia Cooke along to assist - the former making his last film with the brothers, the latter about to become one of their most important collaborators, as well as Ethan Coen's wife), which places establishing shots into the film like great, heavy blocks, leaving long pauses in front of and behind the actors' beats.

It's a methodical, lugubrious tone to define a major location, and Goodman's cheery attitude at once provides a contrast to it while also drawing something out of it. His earnestness itself become, maybe not funny, but certainly worked into the film to give these scenes the cadence of humor, in part because of all the actors in the cast, he feels like the only one delivering the brittle, old-fashioned dialogue in a register that feels like he's actually talking the way that comes naturally to him, rather than because he's performing stylised dialogue in a stylised movie. This isn't to criticise the rest of the cast: it is a stylised movie, and part of the style is having Charlie feel the most natural and human figure in it, the agreeable, soulful figure who, in Goodman's hands, keeps swallowing back his hurt at the way he's being treated by Barton, often doing nothing but twitching his lips and eyelashes while Turturro commands the camera's attention as he speaks. And somehow, on top of all of this, Goodman makes it playful and light, making Barton's arrogance part of the flow of banter, rather than asking us to see Charlie as a put-upon sad sack (which the film could absolutely no survive). He's amusing because he's likable and real, in the midst of a cast full of caricatures and cynicism, and that's the more sarcastic, ironic joke of the whole film, the fact that - SPOILER ALERT - the Coens and Goodman have made Barton such a smug ass that we actually feel sorrier for a serial killing Nazi who is possibly also the actual, literal Devil. END SPOILERS

A final note on this film too big and complex for any truly final note: it's immaculately crafted, of course, that's true of even the very shitty Coen brothers movies. It lacks the sharp edge of Miller's Crossing, never screaming that we notice its form the way that film's editing and camera movements do, but it's no less precise and perfect. I have mentioned the visual contrast between the sunshine of southern California and the solemn gloom of the hotel, and the latter location, in particular, is a triumph of using just the right amount of ghostly light to make the space seem sepulchral, particularly as the hallways are framed to make their oppressive rectangular linearity dominate the composition - they are the most plunging, deep, infinite hallways I have ever seen, suggesting even more than all the screenplay put together that the Earle is a space out of time, a joyless spiritual plane of dusty and mildew. The steady movements of the camera, the way that the composition and lens choices box Barton and Charlie in as they talk, these are all superb visuals, less flashy than Miller's Crossing, less rich, but they get into you at a deeper emotional level. Not that the brighter scenes outside the hotel aren't well done (there's a scene at a USO dance that's particularly striking, feeling more docu-realist than anything else in the film, and paradoxically feeling completely unreal because of it), or immaculately composed, but they're not as good at the scenes in the Earle of showing of the great talent of British cinematographer Roger Deakins, a relative newcomer to American filmmaking whom the Coens lucked into hiring after Barry Sonnenfeld had abandoned cinematography to direct The Addams Family. Deakins's earlier films, the little bit I'm familiar with, aren't the work of a slouch, by any means (what I've seen of Nineteen Eighty-Four looks especially impressive), but they don't strike one as the work of a genuine genius the way his Hotel Earle interiors do, his first masterpiece. We'll be hearing from this crazy cinematographer, and I don't mean a postcard.

That certainly isn't the most outlandish reading I can think of for a movie with a calculated indifference to yielding up meaning. I mean, on the one hand, it's quite straightforward: Barton Fink (John Turturro), a fairly new playwright in 1941, is convinced that he's on the brink of telling a great new story about the American working class, one that will revolutionise American theatre; he is, however a hypocrite and dilettante whose interest in the working class is strictly aesthetic and whose high-minded progressive ideals are mostly about declaring his virtue publicly and thereby impressing his high-minded progressive peers, and who blatantly does not care about the actual working class as it is constituted of individual people, but only as an ideal he has constructed. A message with absolutely no application to our own times, obviously. The Coens have a great deal of fun mocking him - he is the most obnoxious protagonist in any Coen film, maybe even the only one who's genuinely unlikable - by shipping him off to Hollywood, where his extremely self-important awareness of his writing skills proves incapable of the laughably uncomplicated task of writing a formulaic B-picture about wrestlers, a perfectly everyday genre that this self-anointed poet of the masses has apparently never heard of.

If that's all there was to it - poking fun at the fecklessness of an elite intellectual class so worked up waxing rhapsodic about their ideals that they completely forget to live them - I imagine Barton Fink would still be an enjoyably caustic time. But it's so much more. It's one of the greatest American films of the 1990s, a film that swept the awards at the Cannes International Film Festival so hard (Picture, Director, Actor) that they changed the rules to make sure no film could ever do it again, and still, after all these years and movies, probably the most inexhaustible film the Coens have ever made. For one thing, it's a puzzle, though a puzzle that the Coens have more or less stated outright doesn't have a solution. The film is heavy with symbolism, far more symbolism than any one of their films would possess again, and a lot of it seems frankly inscrutable. Not all of it - some of it is extremely obvious, in fact (the biggest one being that Hotel Earle, where Barton is staying during his trip to Los Angeles, is indicated to be the actual, literal Hell). And some of it seems to obvious in an intuitive way that keeps eluding you when you try to put it into words, like the shot of a seabird plunging into the ocean in the last shot, that the Coens have sworn consistently over the years was a happy accident.

My gut feeling, based more on the rest of the Coens' work than anything Barton Fink directly presents, is that this is a trap. With very few exceptions, these are screenwriters whose favorite mode is one of arch irony, and the ironic take on the film's symbolism goes back to the idea of writer's block. And maybe this is my own bias talking as well, but doesn't it sometimes feel like symbolism is the refuge of a writer who has no ideas and is trying to make them seem fancier by making them opaque? Especially in the case of the mid-century literature of the middlebrow intelligentsia who seem to regard Barton as a great writer - and if I can chase an idea for a moment (but this is a film that encourages dropping what you're doing and running after ideas - it feels deliberately shaggy and meandering after the impeccable mechanics of Miller's Crossing), whether or not he has actual talent is one of the film's great mysteries. The way the film stages his revelations in the second half, when he's finally unblocked, suggests that he's channeling something powerful and divine; but this is immediately undercut with the blunt joke that his big inspiration has been to rip-off his own work, word-for-word. The fatuous praise of middlebrow airheads in the beginning and the anti-intellectual dismissal of a crude studio head in the end both seem to be be neutral evidence at best. I like to imagine that his screenplay is no good, at any rate; the idea that he has made a Faustian pact with the devil (which I think is one of the more obvious bits of symbolism that we can cling to), just to write a mediocre, cliché-ridden bit of midcentury social realism - and not even have the self-awareness to realise it! - feels like an appropriately bitter punchline for the filmmakers who, many years and career twists and turns from this point, would be responsible for Burn After Reading and A Serious Man.

But I was speaking of symbolism, and middlebrow writers relying on it as a crutch to get through writer's block, and part of me can't help but wonder: is that the joke? Especially given that the directors seem to regard their own symbolism as a dead end? Or maybe the joke is on Barton's apparent commitment to the idea that art must be didactic to be meaningful, that everything has to be spelled out and buttoned up. Of the final four sentences that Barton speaks, two of them are "I don't know", and there's no way that's an accident - an author who can't explain anything serving as the final punctuation mark for a couple of authors who won't explain anything.

But perhaps even treating this as a metanarrative joke about writer's block and the Coens' mildly self-negating attitude towards writers who think that they're too good for simply, honest genre mechanics - Barton Fink is one of the most generically slippery movies I can name, and a uniquely impenetrable art film by American standards - perhaps even this goes too far in a movie that feels open to any interpretation as long as we agree that they're all equally wrong. If we go all the way down, maybe the meaning of the film is flagged in a line that, unusually for this film, does jump and down screaming that we notice how immaculately well-built and quippy it is. Audrey Taylor (Judy Davis), the beleagued muse, handmaid, and nanny to a dysfunctional alcoholic former genius writer, and has come over to help Barton crack the mystery of how to write a boilerplate wrestling picture. "Usually, they're... simply morality tales", she says, explaining the basics of Hollywood conflict-building with patronising patience. And perhaps Barton Fink is simply a morality tale, too, though not a simple one, if the distinction makes sense. I hold it to be self-evident that the Coens' filmography broadly breaks into two parts, before and after a three-year gap between 2004's The Ladykillers and 2007's No Country for Old Men, and the difference isn't simply that they were starting to lose their way and then found it. After 2007, their entire filmography, even in the comedies, becomes obsessed with questions of moral behavior in an amoral universe, something that only occasionally shows up in their first run of movies. Morality is a factor in these films, especially 1996's Fargo and 2001's The Man Who Wasn't There, but they're all much more unified by being misadventures about people who think they're more capable than they are getting trapped in a convoluted web of their own creation. Barton Fink has a bit of that - Barton assumes he can sweep out to Los Angeles, bash out a few perfect screenplays, and head back to New York a much richer man - but it's not at all the focus. This is the one film of that first phase of their career that feels like it belongs in the second phase, a grandiose cosmic story about ethics and living with the sins you have committed, already condemned to Hell with no way out. Barton's sins include hypocritically jetting out to Hollywood for money, thinking too highly of his own ability to change the world, looking down on movies that want to be well-built and unpretentious entertainment, and superciliously ignoring Charlie Meadows (John Goodman), the ebullient, eager-to-please salesman who lives in the room next door at the Earle, preferring to talk at him rather than engage him as a fellow human, and that these are what the Coens choose to send him to Hell for speaks to their moral worldview rather cleanly, I think.

What you might not guess from all of that is that Barton Fink is a delight to watch. This is the film where the Coens figured out the knack for comedy that would follow them the rest of their career: 1984's Blood Simple isn't very funny at all, and 1987's Raising Arizona is a big silly farce, and Miller's Crossing is very "clever" but not really "funny". Barton Fink hits the sweet spot that the brothers would keep hitting thereafter: a sharp, barking, absurdist sense of humor that intertwines with the heavy weight of the story so intimately that it's often impossible to tell if we're watching a particularly morbid dark comedy, or a particularly hilarious tragedy. Barton Fink is clearly not "a comedy", though it's often funny as hell. Transparently so, in its tour of Hollywood venality, embodied by the giddy performance of Michael Lerner as Jack Lipnick, the force of pure will who runs the studio that Barton has gotten a contract with. It's a sublime marriage of performer and part, resulting in line after line of breathtaking screwball banter, charged with a perfect level of toxic indifference masked by bonhomie. It's not the only great purely comic performance: Tony Shalhoub's gravelly producer and John Mahoney's vulgar drunk author are both pitched exactly where they need to be as well, while Davis and Jon Polito are both funny and deeply melancholy as toadies with a broken sense of their own self worth.

But the highlight, both of acting, and of getting at the Coens' brilliant new comic sensibility, is surely Goodman, whose performance as Charlie is in the running for the best acting in any Coen film. Part of the film's very strange comic strategy is to sharply contrast the fast-moving dialogue and brightly-lit spaces of L.A. with the slow, dusky interiors of the Hotel Earle, and Goodman's performance is the anchor to that space (along with a glorious small role for Steve Buscemi as the inhumanly upbeat bellhop Chet). The film slows down incredibly inside the hotel, lingering on the droning rhythm of a bad air conditioning system deep in the sound mix (augmented by composer Carter Burwell's extremely sparing use of fragments of bass music - this is one of the two least-musical of all Coen films, but it uses its score with unmatched precision), and other sound effects plucked very deliberately to ride atop the mix, creating a space that feels constructed one piece at a time. That vibe carries over on to the editing (the Coens cut this film themselves, with Michael Berenbaum and Tricia Cooke along to assist - the former making his last film with the brothers, the latter about to become one of their most important collaborators, as well as Ethan Coen's wife), which places establishing shots into the film like great, heavy blocks, leaving long pauses in front of and behind the actors' beats.

It's a methodical, lugubrious tone to define a major location, and Goodman's cheery attitude at once provides a contrast to it while also drawing something out of it. His earnestness itself become, maybe not funny, but certainly worked into the film to give these scenes the cadence of humor, in part because of all the actors in the cast, he feels like the only one delivering the brittle, old-fashioned dialogue in a register that feels like he's actually talking the way that comes naturally to him, rather than because he's performing stylised dialogue in a stylised movie. This isn't to criticise the rest of the cast: it is a stylised movie, and part of the style is having Charlie feel the most natural and human figure in it, the agreeable, soulful figure who, in Goodman's hands, keeps swallowing back his hurt at the way he's being treated by Barton, often doing nothing but twitching his lips and eyelashes while Turturro commands the camera's attention as he speaks. And somehow, on top of all of this, Goodman makes it playful and light, making Barton's arrogance part of the flow of banter, rather than asking us to see Charlie as a put-upon sad sack (which the film could absolutely no survive). He's amusing because he's likable and real, in the midst of a cast full of caricatures and cynicism, and that's the more sarcastic, ironic joke of the whole film, the fact that - SPOILER ALERT - the Coens and Goodman have made Barton such a smug ass that we actually feel sorrier for a serial killing Nazi who is possibly also the actual, literal Devil. END SPOILERS

A final note on this film too big and complex for any truly final note: it's immaculately crafted, of course, that's true of even the very shitty Coen brothers movies. It lacks the sharp edge of Miller's Crossing, never screaming that we notice its form the way that film's editing and camera movements do, but it's no less precise and perfect. I have mentioned the visual contrast between the sunshine of southern California and the solemn gloom of the hotel, and the latter location, in particular, is a triumph of using just the right amount of ghostly light to make the space seem sepulchral, particularly as the hallways are framed to make their oppressive rectangular linearity dominate the composition - they are the most plunging, deep, infinite hallways I have ever seen, suggesting even more than all the screenplay put together that the Earle is a space out of time, a joyless spiritual plane of dusty and mildew. The steady movements of the camera, the way that the composition and lens choices box Barton and Charlie in as they talk, these are all superb visuals, less flashy than Miller's Crossing, less rich, but they get into you at a deeper emotional level. Not that the brighter scenes outside the hotel aren't well done (there's a scene at a USO dance that's particularly striking, feeling more docu-realist than anything else in the film, and paradoxically feeling completely unreal because of it), or immaculately composed, but they're not as good at the scenes in the Earle of showing of the great talent of British cinematographer Roger Deakins, a relative newcomer to American filmmaking whom the Coens lucked into hiring after Barry Sonnenfeld had abandoned cinematography to direct The Addams Family. Deakins's earlier films, the little bit I'm familiar with, aren't the work of a slouch, by any means (what I've seen of Nineteen Eighty-Four looks especially impressive), but they don't strike one as the work of a genuine genius the way his Hotel Earle interiors do, his first masterpiece. We'll be hearing from this crazy cinematographer, and I don't mean a postcard.