Ocean of secrets

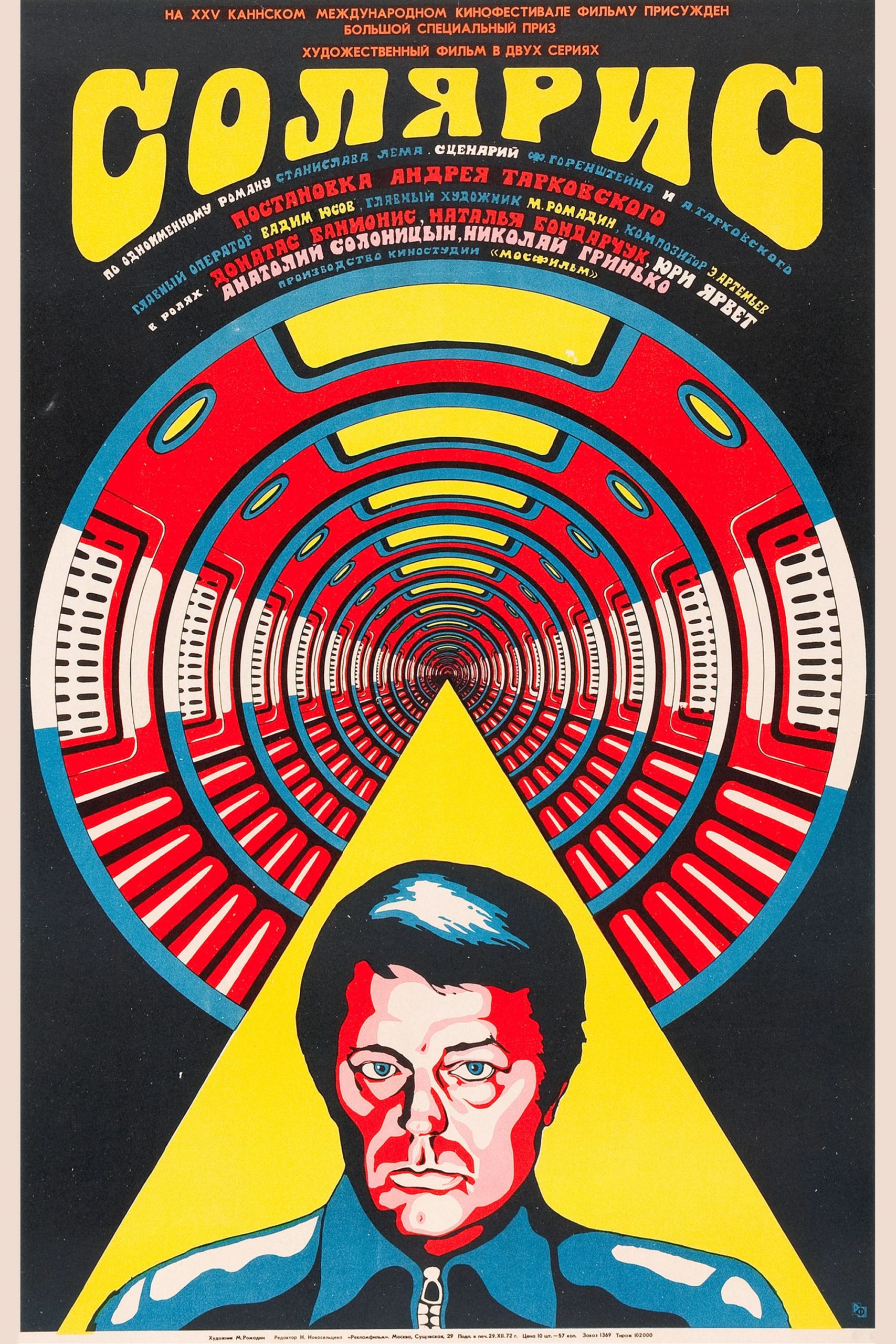

The most amusing thing about the 1972 adaptation of Solaris - a film about which very little is amusing, to be fair - is that Andrei Tarkovsky made it, basically, as a "one for them" project. His previous feature, Andrei Rublev, had met with enormous hostility upon delivery, and was shelved for five years; his proposed follow-up, a script concept called Confession among several other working titles, was rejected for its obscurantism and formal complexity. His decision to make a feature film adaptation of Stanisław Lem's 1961 novel (which was adapted as a two-part television movie in the Soviet Union in 1968, right around the time Tarkovsky was first considering the book as a potential project) was motivated in no small part by the belief that an already-vetted story in an audience-friendly genre would glide through the approval process with relatively little effort. He was right, and the result was his only Soviet-produced project after Ivan's Childhood that was made without any significant crises.

And you know, if we're going to be so wanton as to call any of Tarkovsky's post-Ivan work "audience-friendly", I guess Solaris is the best candidate for that title. It's generally much more forthcoming about its themes, even going so far as to put some of them directly in the mouths of characters. It's possible to explain the entire plot without having to ever guess about any of it. Virtually all of the characters have names. Compared to 1975's Mirror and 1979's Stalker, it's downright penetrable.

Still and all, and even if at some distant remove, the idea was to make something accessible enough to get the censors off his back, this film still finds Tarkovsky making a Tarkovsky movie of 166 ponderous minutes, with all the visionary obscurantism that suggests. I have, not even facetiously, made a habit of referring to it (and thinking of it) as "the one with the five-minute driving scene", on account of there's a scene that lasts for five minutes, of somebody driving in moderate traffic. This is not a necessary development of the plot (we never see the driver's destination - in fact, we never see the driver again). It is punishingly dull. It's also almost certainly my favorite part of this movie and maybe my favorite part of any movie made in the 1970s, so there we go.

More to the point, Tarkovsky was perfectly unafraid to break the novel open to get inside and peek at what he cared about. Lem hated the film, which he thought completely mangled the message of the book, and in a sense he's right: the novel Solaris is hard science fiction about the complexities of communicating with one of the most genuinely alien extra-terrestrial intelligences in the genre's history; the hero spends fully half of the story doing secondary document research on the subject. The film Solaris includes some of that material, but it dumps many of the secrets Lem threaded across the novel right in one graceless scene near the start, and presents all of the knowledge that must be fought for by the novel's scientists as having already been discovered before we even know there's a mystery to be cracked. In the process, it makes the main character much less active - he never has to do any work, and one of the other characters even yells at him about this.

But to say that Tarkovsky missed the point of the book is inapt; better to say that he ignored the point of the book, and latched onto a different point that he found more interesting. The story of Solaris, is that there is a space station hovering above the surface of Solaris, a most peculiar planet almost entirely covered by an ocean that appears to function as a kind of brain. Decades of Solaricists - scientists who have devoted their entire careers to figuring out just what the fuck is up with this situation - have come up with only very meager solutions, and it's increasingly looking like the station might end up getting scrapped soon. At the moment, there are only three people on the station, soon to be joined by a fourth, psychologist Kris Kelvin (Donatas Banionis, overdubbed by Vladimir Zamansky). When he arrives, he finds something that resembles a haunted house more than a research facility, and he's even more unnerved to learn from Dr. Snaut (Jüri Järvet, overdubbed by Vladimir Tatosov), who is quite drunk at the time, that Kelvin's mentor Dr. Gibarian (Sos Sargsyan) has recently committed suicide. Snaut won't talk about the reasons why, but Kelvin starts to figure out pretty quickly that all three men - the third being the reclusive, haughty Dr. Sartorius (Anatoly Solonitsyn) - have each received their own "guests", figures looking like humans who absolutely shouldn't be there, and whose presence is certainly enough to drive you made, especially for Kelvin, whose guest takes the form of his dead wife, Hari (Natalya Bondachuk).

The big change that Tarkovsky and co-writer Friedrich Gorenstein make is one of emphasis: this is a film about Kelvin's relationship to the simulacrum - simulacra, to be precise - of Hari, and as such about his relationship to his guilt and regrets about his past. In short, even if he couldn't make Confession, which was to be a complex dive into how memory works, he'd still find a way to make Confession (it ended up seeing the light of day as Mirror).

I say "the" big change, but there are several. The other one is that Tarkovsky's Solaris opens with an exceptionally slow, methodical stretch of time on Earth, before Kelvin leaves for the station, where we get to meet his parents (Nikolai Grinko, Olga Barnet). Formally speaking, we're also here to meet Berton (Vladislav Dvorzhetsky), a retired pilot and friend of the older Kelvins, who had an extraordinary experience on Solaris that has been officially regarded as a hallucination it's through him, and the very old recording of his deposition, that we get all of the exposition in one big blob, but even in the act of receiving this exposition, it's hard to claim that the film takes it particularly seriously, or expect us to do the same.

The opening 45 minutes of Solaris are much more about insisting on a slow, unhurried rhythm, slower even than anything in the monolithic Andrei Rublev. The film opens, in a splendid perversity for a film about the complexities of space travel and what we might find in the galaxy, with close-up shots of weeds drifting in a pond, and from there to find Kelvin aimlessly wandering through a field; it's aggressive languorous, if that's something that can exist, all the better to give us a sense of the sonic and visual richness of Earth, and all that Kelvin leaves behind. When Berton's deposition comes in, it's easier to think about in terms of this richness, than to focus on the exposition; for me, at least, the sequence is mostly about how the razor-sharp black-and-white cinematography contrasts with the muddy, bleeding colors of the present day scenes wrapped around it, both more and less vibrant and bold (the film was shot by Vadim Yusov, working with Tarkovsky for the fourth and final time).

This leads in short order to Berton's drive back to the city, and what I will always consider one of the film's signature moments, that five-minute traffic sequence. I tend to misremember this as one uninterrupted shot through the front window of the car; in fact, we get several angles of the interior of the car to break this up, and a couple of aerials of a busy exchange of highways going over and under each other. Still, though, it's a pretty long stretch of absolutely nothing at all, shot in a very weird mixture of color and black and white that looks, at first to be completely arbitrary. Hell, maybe is arbitrary. Tarkovsky joked (?) that this sequence was there to scare off the impatient viewers who weren't up to the challenges of his glacial art movie, but it would be an insult to him and the film to take that at face value. As with any film worth caring about, I can only offer my own opinion, and happily report that it is certainly not one that anybody has to care about, but I think it goes a little bit something like this: black-and-white tends to correlate with the past. The footage of young Berton's deposition starts that off, in a very bland, obvious way. Later on in the film, black-and-white footage that has been toned blue or amber, or just left black and white, is pretty clearly assigned to memories - not memory-in-the-flesh, as with the Hari clone, but with actual, subjective memories. The driving sequence, however, switches back and forth, and then ends with Kelvin, at his parents' home, in monochrome.

And here's where I need to switch gears to another bit of speculation that might have nothing to do with anything. Tarkovsky very famously hated Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey, from 1968 (Kubrick returned the favor), and claimed that Solaris was meant to be its antithesis, after a fashion. I really don't want to belabor that, because I think it suggests you can only love one or the other, when it's much more fun to think of them as the two best science fiction movies ever made, but it's worth at least keeping it in the back of our minds. 2001, of course, includes achingly long sequences of slow-moving space travel, and it's hard not to think of the driving scenes as an echo of that. We never see space travel in this film: Kelvin goes from that monochrome sequence at his parents' home to approaching the station, in a close-up of his face that shows us nothing of the vacuum of space. But the driving sequence mimics it, in a way: electronic sound effects have been piped in, ironically adding a sense of futuristic gloss to the plain, ugly cars of the early '70s, and much of the sequence consists of driving through tunnels, lit with strips of light at the top that go streaking by, in a playful low-fi appoximation of warp drive or hyperspace. Kubrick's film is all about showcasing the technological wonders of the future (and then making them either boring or hostile); Tarkovsky, in the opening 45 minutes of Solaris, seems more interested in making a banal, everyday vision of the contemporary world, in housing and cars and landscape and technology, force itself into a sci-fi setting. The hopeful future looks exactly like 1972, and this gets to the heart of what the filmmaker wanted to do here: jettison all of the trappings of science fiction, and focus on an everyday, here-and-now human story, one that required the matter of sci-fi to justify creating a Hari clone, but cares almost exclusively about the fact that the clone exists. He makes the station look deeply unmagical, staging it in repetitive, claustrophobic shots that make the rounded surfaces of the station look more shapeless and hollow than sleek and futuristic. So why not transform the matter of space travel into an aimless sequence of driving in traffic - traffic that is rather more beautiful than almost anything else that follows, I might add, especially in those aerial shots.

So back to the eccentric use of black-and-white. The other thing the film is about, of course, is the permeable relationship between now and then, memory and the present. The shift to color pulls the footage of Berton, a man associated with the past, into the present; if I'm right that traffic is this film's sarcastic representation of space travel, maybe it's even when we shift over to Kelvin's trip to Solaris. And then the shift back to Kelvin at his parents' home in blue-toned black-and-white consigns that home, and the pond and plants, to the past. A slurry confusion about when the present becomes the past is exactly what the film wants to work with, so transitioning from Earth to the station in a confusing exchange of apparently conflicting stylistic data points seems like just the right way to do it.

So now, over a thousand words later, let's get back to the film's own present, the matter of Kelvin and Hari. The film does away with the book's treatment of this situation as a mystery - or rather, it doesn't present it as a mystery that anyone is obviously working to solve. Snaut and Sartorious tell Kelvin things that they've figured out, at points. For him, and thus for us, this is much more about the way that the great failure of his past (which the film does turn into a mystery; the book lets us know what happened to the real Hari almost immediately, whereas the film substantially delays it, because for the movie, that's the interesting and telling question, not matters of neutrinos and sentient oceans) is both coming back to haunt him, but has also been erased: this Hari is based on his memories, not on reality, and thus in a sense is only reflecting back what Kelvin wants to remember. But then, as the film progresses, and breaks all the way away from Lem, Hari evolves - she becomes real, in a sense, and real means that she no longer hews towards Kelvin's good or bad memories. She becomes her own person, and it's Bondarchuk's triumph to slowly reveal how this happens, gradually phasing in facial expressions and body language that complicate Hari from the sci-fi automaton we meet at first. Thus the film becomes even more complicated than simply the past interrupting the present, for in the act of doing so, the past ceases to be the past, but has instead turned into something new.

This is a less opaque version of what Tarkovsky would get up to with Mirror, but it's still pretty daunting to try and hack through all of the complexities that Solaris has for us; and I've mostly only even nodded towards the narrative complexities. There's a whole visual art object on top of that, one that uses the camera with a chilly precision: a lot of short lateral pans and not much other camera movement, certainly compared to the floating cinematography of Andrei Rublev, and I have already mentioned the way that the film keeps re-using certain compositions and set-ups to amplify how unpleasantly close the hallways of the station are, especially when a number of those compositions call attention to the floor and ceiling of rooms. This unromantic, unspectacular vision of life in space contrasts with the brief injections of messy life - Gibarian's torn-up room is an obvious example, and it's shot with a completely different set of angles than anything else (even Kelvin's room feels repetitive and mechanical, perhaps as an extension of how he's trying to live a strict, orderly life with his new Hari). The film also gets a lot of mileage from occasionally breaking reality using some very simple staging tricks (having actors walk around behind the camera to show up on the other side, giving several women identical wigs and then never showing their face) to create an uncanny, ghostly atmosphere that's still resolutely intimate. There are no large-scale freakouts beyond the infinite here.

The whole thing is perfectly immaculate, basically, using the chilliness of the way the location is framed (and the frequent dead silence, where literally everything drops off of the soundtrack) to offset the profoundly human story being told there. At times, it combines these, such as when Hari's face is distorted and split in two by a mirrored surface; and occasionally, mostly in the last half-hour, it dives into some completely other style, to craft striking, unusual sequences that feel startling and alien even within this film's context, the better to accentuate the moments when Hari and Kelvin's relationship bends into some new direction. It is a film so controlled that even the slightest hint of loosening that control is both exciting and terrifying simultaneously - and that's kind of everything isn't it? That's the film's relationship to space travel, to love, to the matter of being human - the parts we can't control are the ones that are best, and also likeliest to kill us. That's hardly the biggest part of the film's aesthetic, but the moments of unplanned chaos, even if it's small scale - drifting weeds, traffic swerving, unexpectedly fast editing in the midst of all the long takes, and so on - are all the ones that strike me as the most memorable, and that doesn't seem likely to be a coincidence.

And you know, if we're going to be so wanton as to call any of Tarkovsky's post-Ivan work "audience-friendly", I guess Solaris is the best candidate for that title. It's generally much more forthcoming about its themes, even going so far as to put some of them directly in the mouths of characters. It's possible to explain the entire plot without having to ever guess about any of it. Virtually all of the characters have names. Compared to 1975's Mirror and 1979's Stalker, it's downright penetrable.

Still and all, and even if at some distant remove, the idea was to make something accessible enough to get the censors off his back, this film still finds Tarkovsky making a Tarkovsky movie of 166 ponderous minutes, with all the visionary obscurantism that suggests. I have, not even facetiously, made a habit of referring to it (and thinking of it) as "the one with the five-minute driving scene", on account of there's a scene that lasts for five minutes, of somebody driving in moderate traffic. This is not a necessary development of the plot (we never see the driver's destination - in fact, we never see the driver again). It is punishingly dull. It's also almost certainly my favorite part of this movie and maybe my favorite part of any movie made in the 1970s, so there we go.

More to the point, Tarkovsky was perfectly unafraid to break the novel open to get inside and peek at what he cared about. Lem hated the film, which he thought completely mangled the message of the book, and in a sense he's right: the novel Solaris is hard science fiction about the complexities of communicating with one of the most genuinely alien extra-terrestrial intelligences in the genre's history; the hero spends fully half of the story doing secondary document research on the subject. The film Solaris includes some of that material, but it dumps many of the secrets Lem threaded across the novel right in one graceless scene near the start, and presents all of the knowledge that must be fought for by the novel's scientists as having already been discovered before we even know there's a mystery to be cracked. In the process, it makes the main character much less active - he never has to do any work, and one of the other characters even yells at him about this.

But to say that Tarkovsky missed the point of the book is inapt; better to say that he ignored the point of the book, and latched onto a different point that he found more interesting. The story of Solaris, is that there is a space station hovering above the surface of Solaris, a most peculiar planet almost entirely covered by an ocean that appears to function as a kind of brain. Decades of Solaricists - scientists who have devoted their entire careers to figuring out just what the fuck is up with this situation - have come up with only very meager solutions, and it's increasingly looking like the station might end up getting scrapped soon. At the moment, there are only three people on the station, soon to be joined by a fourth, psychologist Kris Kelvin (Donatas Banionis, overdubbed by Vladimir Zamansky). When he arrives, he finds something that resembles a haunted house more than a research facility, and he's even more unnerved to learn from Dr. Snaut (Jüri Järvet, overdubbed by Vladimir Tatosov), who is quite drunk at the time, that Kelvin's mentor Dr. Gibarian (Sos Sargsyan) has recently committed suicide. Snaut won't talk about the reasons why, but Kelvin starts to figure out pretty quickly that all three men - the third being the reclusive, haughty Dr. Sartorius (Anatoly Solonitsyn) - have each received their own "guests", figures looking like humans who absolutely shouldn't be there, and whose presence is certainly enough to drive you made, especially for Kelvin, whose guest takes the form of his dead wife, Hari (Natalya Bondachuk).

The big change that Tarkovsky and co-writer Friedrich Gorenstein make is one of emphasis: this is a film about Kelvin's relationship to the simulacrum - simulacra, to be precise - of Hari, and as such about his relationship to his guilt and regrets about his past. In short, even if he couldn't make Confession, which was to be a complex dive into how memory works, he'd still find a way to make Confession (it ended up seeing the light of day as Mirror).

I say "the" big change, but there are several. The other one is that Tarkovsky's Solaris opens with an exceptionally slow, methodical stretch of time on Earth, before Kelvin leaves for the station, where we get to meet his parents (Nikolai Grinko, Olga Barnet). Formally speaking, we're also here to meet Berton (Vladislav Dvorzhetsky), a retired pilot and friend of the older Kelvins, who had an extraordinary experience on Solaris that has been officially regarded as a hallucination it's through him, and the very old recording of his deposition, that we get all of the exposition in one big blob, but even in the act of receiving this exposition, it's hard to claim that the film takes it particularly seriously, or expect us to do the same.

The opening 45 minutes of Solaris are much more about insisting on a slow, unhurried rhythm, slower even than anything in the monolithic Andrei Rublev. The film opens, in a splendid perversity for a film about the complexities of space travel and what we might find in the galaxy, with close-up shots of weeds drifting in a pond, and from there to find Kelvin aimlessly wandering through a field; it's aggressive languorous, if that's something that can exist, all the better to give us a sense of the sonic and visual richness of Earth, and all that Kelvin leaves behind. When Berton's deposition comes in, it's easier to think about in terms of this richness, than to focus on the exposition; for me, at least, the sequence is mostly about how the razor-sharp black-and-white cinematography contrasts with the muddy, bleeding colors of the present day scenes wrapped around it, both more and less vibrant and bold (the film was shot by Vadim Yusov, working with Tarkovsky for the fourth and final time).

This leads in short order to Berton's drive back to the city, and what I will always consider one of the film's signature moments, that five-minute traffic sequence. I tend to misremember this as one uninterrupted shot through the front window of the car; in fact, we get several angles of the interior of the car to break this up, and a couple of aerials of a busy exchange of highways going over and under each other. Still, though, it's a pretty long stretch of absolutely nothing at all, shot in a very weird mixture of color and black and white that looks, at first to be completely arbitrary. Hell, maybe is arbitrary. Tarkovsky joked (?) that this sequence was there to scare off the impatient viewers who weren't up to the challenges of his glacial art movie, but it would be an insult to him and the film to take that at face value. As with any film worth caring about, I can only offer my own opinion, and happily report that it is certainly not one that anybody has to care about, but I think it goes a little bit something like this: black-and-white tends to correlate with the past. The footage of young Berton's deposition starts that off, in a very bland, obvious way. Later on in the film, black-and-white footage that has been toned blue or amber, or just left black and white, is pretty clearly assigned to memories - not memory-in-the-flesh, as with the Hari clone, but with actual, subjective memories. The driving sequence, however, switches back and forth, and then ends with Kelvin, at his parents' home, in monochrome.

And here's where I need to switch gears to another bit of speculation that might have nothing to do with anything. Tarkovsky very famously hated Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey, from 1968 (Kubrick returned the favor), and claimed that Solaris was meant to be its antithesis, after a fashion. I really don't want to belabor that, because I think it suggests you can only love one or the other, when it's much more fun to think of them as the two best science fiction movies ever made, but it's worth at least keeping it in the back of our minds. 2001, of course, includes achingly long sequences of slow-moving space travel, and it's hard not to think of the driving scenes as an echo of that. We never see space travel in this film: Kelvin goes from that monochrome sequence at his parents' home to approaching the station, in a close-up of his face that shows us nothing of the vacuum of space. But the driving sequence mimics it, in a way: electronic sound effects have been piped in, ironically adding a sense of futuristic gloss to the plain, ugly cars of the early '70s, and much of the sequence consists of driving through tunnels, lit with strips of light at the top that go streaking by, in a playful low-fi appoximation of warp drive or hyperspace. Kubrick's film is all about showcasing the technological wonders of the future (and then making them either boring or hostile); Tarkovsky, in the opening 45 minutes of Solaris, seems more interested in making a banal, everyday vision of the contemporary world, in housing and cars and landscape and technology, force itself into a sci-fi setting. The hopeful future looks exactly like 1972, and this gets to the heart of what the filmmaker wanted to do here: jettison all of the trappings of science fiction, and focus on an everyday, here-and-now human story, one that required the matter of sci-fi to justify creating a Hari clone, but cares almost exclusively about the fact that the clone exists. He makes the station look deeply unmagical, staging it in repetitive, claustrophobic shots that make the rounded surfaces of the station look more shapeless and hollow than sleek and futuristic. So why not transform the matter of space travel into an aimless sequence of driving in traffic - traffic that is rather more beautiful than almost anything else that follows, I might add, especially in those aerial shots.

So back to the eccentric use of black-and-white. The other thing the film is about, of course, is the permeable relationship between now and then, memory and the present. The shift to color pulls the footage of Berton, a man associated with the past, into the present; if I'm right that traffic is this film's sarcastic representation of space travel, maybe it's even when we shift over to Kelvin's trip to Solaris. And then the shift back to Kelvin at his parents' home in blue-toned black-and-white consigns that home, and the pond and plants, to the past. A slurry confusion about when the present becomes the past is exactly what the film wants to work with, so transitioning from Earth to the station in a confusing exchange of apparently conflicting stylistic data points seems like just the right way to do it.

So now, over a thousand words later, let's get back to the film's own present, the matter of Kelvin and Hari. The film does away with the book's treatment of this situation as a mystery - or rather, it doesn't present it as a mystery that anyone is obviously working to solve. Snaut and Sartorious tell Kelvin things that they've figured out, at points. For him, and thus for us, this is much more about the way that the great failure of his past (which the film does turn into a mystery; the book lets us know what happened to the real Hari almost immediately, whereas the film substantially delays it, because for the movie, that's the interesting and telling question, not matters of neutrinos and sentient oceans) is both coming back to haunt him, but has also been erased: this Hari is based on his memories, not on reality, and thus in a sense is only reflecting back what Kelvin wants to remember. But then, as the film progresses, and breaks all the way away from Lem, Hari evolves - she becomes real, in a sense, and real means that she no longer hews towards Kelvin's good or bad memories. She becomes her own person, and it's Bondarchuk's triumph to slowly reveal how this happens, gradually phasing in facial expressions and body language that complicate Hari from the sci-fi automaton we meet at first. Thus the film becomes even more complicated than simply the past interrupting the present, for in the act of doing so, the past ceases to be the past, but has instead turned into something new.

This is a less opaque version of what Tarkovsky would get up to with Mirror, but it's still pretty daunting to try and hack through all of the complexities that Solaris has for us; and I've mostly only even nodded towards the narrative complexities. There's a whole visual art object on top of that, one that uses the camera with a chilly precision: a lot of short lateral pans and not much other camera movement, certainly compared to the floating cinematography of Andrei Rublev, and I have already mentioned the way that the film keeps re-using certain compositions and set-ups to amplify how unpleasantly close the hallways of the station are, especially when a number of those compositions call attention to the floor and ceiling of rooms. This unromantic, unspectacular vision of life in space contrasts with the brief injections of messy life - Gibarian's torn-up room is an obvious example, and it's shot with a completely different set of angles than anything else (even Kelvin's room feels repetitive and mechanical, perhaps as an extension of how he's trying to live a strict, orderly life with his new Hari). The film also gets a lot of mileage from occasionally breaking reality using some very simple staging tricks (having actors walk around behind the camera to show up on the other side, giving several women identical wigs and then never showing their face) to create an uncanny, ghostly atmosphere that's still resolutely intimate. There are no large-scale freakouts beyond the infinite here.

The whole thing is perfectly immaculate, basically, using the chilliness of the way the location is framed (and the frequent dead silence, where literally everything drops off of the soundtrack) to offset the profoundly human story being told there. At times, it combines these, such as when Hari's face is distorted and split in two by a mirrored surface; and occasionally, mostly in the last half-hour, it dives into some completely other style, to craft striking, unusual sequences that feel startling and alien even within this film's context, the better to accentuate the moments when Hari and Kelvin's relationship bends into some new direction. It is a film so controlled that even the slightest hint of loosening that control is both exciting and terrifying simultaneously - and that's kind of everything isn't it? That's the film's relationship to space travel, to love, to the matter of being human - the parts we can't control are the ones that are best, and also likeliest to kill us. That's hardly the biggest part of the film's aesthetic, but the moments of unplanned chaos, even if it's small scale - drifting weeds, traffic swerving, unexpectedly fast editing in the midst of all the long takes, and so on - are all the ones that strike me as the most memorable, and that doesn't seem likely to be a coincidence.