War boy

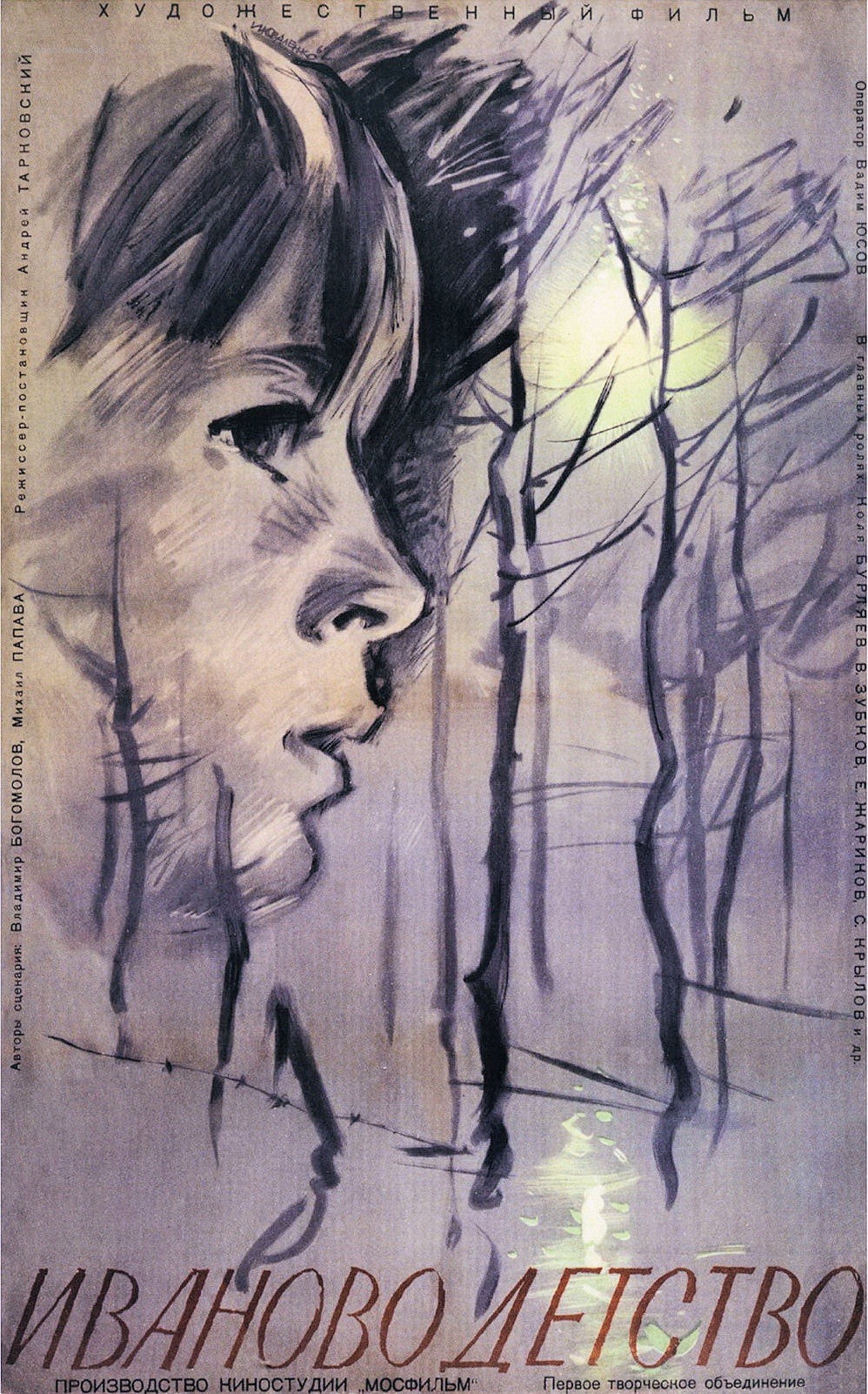

I wonder, if I didn't already know that Ivan's Childhood was possibly my least favorite and certainly the least audacious and ambitious of the seven feature films directed by Andrei Tarkovsky, if I'd be less inclined to nitpick it. Taken solely in the context of the Soviet art cinema of the late 1950s and early '60s, when the cultural liberalisation of the Kruschev Thaw had started to show up in the cinema, leading to films that were harder both intellectually and aesthetically than the studiously trivial movies of the Stalinist era, and Soviet Cinema became internationally celebrated on the backs of the Cannes success of The Cranes Are Flying in 1958 and Ballad of a Soldier in 1960, and it's an extraordinarily impressive work. It's astonishingly handsome, with cinematographer Vadim Yusov (shooting his second Tarkovsky film of four, following the thesis project The Steamroller and the Violin) playing with velvety blacks that make the whole thing seem darker and gloomier than its already lush array of greys would. And this is the kind of film that makes "lush greys" seem like a reasonable description, rather than the ravings of a madman. It's like the images are made out of fog that has coalesced into solid shapes, interrupted only by the beautiful but austere presence of towering birch trees that make a forest feel like some kind of cathedral of glowing white nature.

We'll get back there, but for now, let us consider the scenario. It's the story of a 12-year-old boy, Ivan (Nikolai Burlyayev, who was closer to 16, but looks young for his age), who has found himself orphaned and angry over the course of World War II, and has made himself valuable as a reconnaissance scout at an outpost in some unpopulated waste, at the intersection of a river, a marshland, and a forest. There's not much in the way of story here (it was adapted by Vladimir Bogomolov and Mikhail Papava from Bogomolov's 1957 short story Ivan, with the script then polished by Tarkovsky and Andrei Konchalovsky) more of a succession of impressions, all of them leading up to the notion that war is extremely miserable and awful and unglamorous, all the more so when it can be play out with maximum bitter irony by contrasting it with a kid.

Hell, even the title is a bitter irony: Ivan's childhood, we are invited to sourly think, is no childhood at all, but a gross acceleration of cynical, violent adulthood. Hence his very first dialogue scene, which Burlyayev plays with robotic coldness as he mirthlessly barks out demands of the amused, though increasingly disconcerted Lt. Galtsev (Evgeny Zharikov), who refuses to believe at first that this grubby little boy demanding to send a report to headquarters can possibly be serious. Well, of course he is; this is a Russian art film, and everything in them is serious at all times.* Burlyayev's performance is a bit more uneven than I think the film would like, but the limitations of his acting mostly benefit this aspect of the character: he's got an inflexible hardness that works well to suggest how much fury is being clamped down as Ivan transforms himself from a boy to a machine in the cog of war.

Tarkovsky is infuriated by a world that would let this happen, and he makes sure we feel it too: the film's opening scenes cover Burlyayev in slick black grime that provides a repulsive contrast to his soft features, providing a stark visualisation of the violation of childhood innocence as very nearly the first image of his movie. Ivan's Childhood is not looking to be subtle. This isn't to say that it lacks sophistication - it is a very elegant and even immaculate piece of filmmaking - but it's not subtle. It doesn't want to be: it's a punishingly bleak anti-war film, part of the first generation of Soviet films that had political clearance to be so, and it's clear that nobody involved in making it wanted to leave any doubt about their intentions.

About that immaculate filmmaking: this is a film that was clearly the work of a thoughtful director who had a clear reason for every decision he made, and this is where things get complicated. Ivan's Childhood is very, as it were, "visible" filmmaking. To their luxurious use of greyscale, Tarkovsky and Yusov have added camera movement, and intense, cavernous deep staging, and it these things make it very clear that we should be paying attention to how they work. I have no real problem with that as such, except that part of me has seen all of the director's later films, which cumulatively represent what I might very well argue is the the most impeccable body of work in the history of sound cinema. Part of what makes them so powerful is that the films have a way of pulling us in and letting us sink into them, organically and effortlessly. Tarkovsky has a tremendous command of film form beyond a shadow of a doubt, but in his mature masterpieces, he doesn't try to impress us with them. We have to come to them ready to do the work. Ivan's Childhood does the work for us - it is a very "readable" film. This is, of course, not a weakness, and if (almost literally) any other director had this as the first - or fifth, or tenth - feature, I don't know it would even cross my mind to bring it up. Much like the film's quickly-paced 95 minutes, which sweep us through the busy hell of war without giving us a chance to catch our breath, and which I can't help but feel suffers from lacking the stately, worshipful stillness of the director's later work.

But let's set that aside: viewed in any context other than as Tarkovsky's uncharacteristic first feature, Ivan's Childhood is a remarkably potent piece of anti-war cinema. Take that deep staging, for example. A large portion of the film takes place in nondescript, dingy, dark rooms, but they are given an extraordinary charge of potential energy from the way that Tarkovsky and Yusov arrange shots to have bright, desperate close-ups crushing up against the camera, while other characters perform their business against in the depths, one half of the frame observing the other half while being conspicuously removed from being able to interact with it. Even better are the shots that make the background about space itself: the interiors have a curious way of feeling both very large and yet clearly boxed-in, in part because of how the depth makes us feel the presence of the walls. This makes the trips into the forest a staggering contrast, with the way that every row of trees seems to recede to an infinite point, coupled with the whiteness of the lighting, feeling almost overwhelmingly free and open.

If anything justifies those birch forest scenes, it's that feeling. Story-wise, the location is mostly associated with a frankly dull love triangle centered round the nurse Masha (Valentina Malyavina), who attracts the attentions of both the boyish Galtsev and the aggressive Capt. Kholin (Valentin Zubkov). It's a bit trite, and the performances in this subplot skew a little to close to the wooden earnestness of the kind of noble films about earnest peasants that had made much of Soviet cinema since the coming of sound feel a bit dopey and uninteresting. It's treated with admirably little sentiment - the hard lighting alone is enough to drain the saccharine quality from these scenes, but it feels too much of a war movie cliché, while also completely ignoring the much more compelling and troubling figure of Ivan himself.

That's where the film's heart is: making us feel horrible through the vessel of this broken non-child. There are only a couple of overt battle scenes in Ivan's Childhood, and they are wonderfully done, but the film is full of a sense of violence that's carried through its dark imagery, as well as the sharp, precise camera movements, and the crispness of the editing, as well as the story structure. Ivan himself is plagued by visions: some are clearly memories of his time with his mother (Irma Tarkovskaya, the director's then-wife), but others seem more like impressionistic fantasies of his memories. And at times, he simply seems overwhelmed by the misery of it all, and the film's present-tense reality twists expressionistically, or in one astonishing sequence, he's assaulted by horrific sounds of war that come only from his own anxiety. The memory sequences - something Tarkovsky would substantially develop in later films - provide a simple, clean contrast both to the gloom of the film and the ethereal hard whiteness of the forest, but they're cut in and out of the film with such abrupt, shocking contrasts in the picture and on the soundtrack, they can never become beatific or calming - they are deeply melancholy, even as they depict peace and family. Even at the end, when one of these visions is employed to give the film something that vaguely resembles a happy ending - after another little visionary sequence that's the bleakest part of the film, one that includes a truly draining shot of Burlyayev rolling over and over on the ground, as the camera, in close up, tries to keep up with him - has to end with a note of literal and figurative death and darkness.

So, a fun time, all in all. It is, at least one of the most apocalyptic anti-war films of its generation, using its dark images and implacable camera movement to suggest the war-torn nowhere that the film is set in is a place of constant hostility and danger. And its story takes the sturdy material of a young man, anxious to revenge himself on the bad guys that killed his family, and strips it of any patriotic romanticism by making the boy himself seem so alien and unrecognisable as a 12-year-old child, and by making his sacrifice seem so pointless by the time the movie ends. It's still the least grueling Tarkovsky feature, despite having the most urgent, immediate moral argument; but it's plenty heavy, one of the greatest anti-war films of the 1960s in part because it is so implacable and bleak.

*Russian cinema is, to my knowledge, the only national film industry that has for any period of time (in the 1900s and 1910s) pursued an explicit strategy of "all of our films need to be depressing and can't have even a trace of comedy" as a matter of product differentiation.

We'll get back there, but for now, let us consider the scenario. It's the story of a 12-year-old boy, Ivan (Nikolai Burlyayev, who was closer to 16, but looks young for his age), who has found himself orphaned and angry over the course of World War II, and has made himself valuable as a reconnaissance scout at an outpost in some unpopulated waste, at the intersection of a river, a marshland, and a forest. There's not much in the way of story here (it was adapted by Vladimir Bogomolov and Mikhail Papava from Bogomolov's 1957 short story Ivan, with the script then polished by Tarkovsky and Andrei Konchalovsky) more of a succession of impressions, all of them leading up to the notion that war is extremely miserable and awful and unglamorous, all the more so when it can be play out with maximum bitter irony by contrasting it with a kid.

Hell, even the title is a bitter irony: Ivan's childhood, we are invited to sourly think, is no childhood at all, but a gross acceleration of cynical, violent adulthood. Hence his very first dialogue scene, which Burlyayev plays with robotic coldness as he mirthlessly barks out demands of the amused, though increasingly disconcerted Lt. Galtsev (Evgeny Zharikov), who refuses to believe at first that this grubby little boy demanding to send a report to headquarters can possibly be serious. Well, of course he is; this is a Russian art film, and everything in them is serious at all times.* Burlyayev's performance is a bit more uneven than I think the film would like, but the limitations of his acting mostly benefit this aspect of the character: he's got an inflexible hardness that works well to suggest how much fury is being clamped down as Ivan transforms himself from a boy to a machine in the cog of war.

Tarkovsky is infuriated by a world that would let this happen, and he makes sure we feel it too: the film's opening scenes cover Burlyayev in slick black grime that provides a repulsive contrast to his soft features, providing a stark visualisation of the violation of childhood innocence as very nearly the first image of his movie. Ivan's Childhood is not looking to be subtle. This isn't to say that it lacks sophistication - it is a very elegant and even immaculate piece of filmmaking - but it's not subtle. It doesn't want to be: it's a punishingly bleak anti-war film, part of the first generation of Soviet films that had political clearance to be so, and it's clear that nobody involved in making it wanted to leave any doubt about their intentions.

About that immaculate filmmaking: this is a film that was clearly the work of a thoughtful director who had a clear reason for every decision he made, and this is where things get complicated. Ivan's Childhood is very, as it were, "visible" filmmaking. To their luxurious use of greyscale, Tarkovsky and Yusov have added camera movement, and intense, cavernous deep staging, and it these things make it very clear that we should be paying attention to how they work. I have no real problem with that as such, except that part of me has seen all of the director's later films, which cumulatively represent what I might very well argue is the the most impeccable body of work in the history of sound cinema. Part of what makes them so powerful is that the films have a way of pulling us in and letting us sink into them, organically and effortlessly. Tarkovsky has a tremendous command of film form beyond a shadow of a doubt, but in his mature masterpieces, he doesn't try to impress us with them. We have to come to them ready to do the work. Ivan's Childhood does the work for us - it is a very "readable" film. This is, of course, not a weakness, and if (almost literally) any other director had this as the first - or fifth, or tenth - feature, I don't know it would even cross my mind to bring it up. Much like the film's quickly-paced 95 minutes, which sweep us through the busy hell of war without giving us a chance to catch our breath, and which I can't help but feel suffers from lacking the stately, worshipful stillness of the director's later work.

But let's set that aside: viewed in any context other than as Tarkovsky's uncharacteristic first feature, Ivan's Childhood is a remarkably potent piece of anti-war cinema. Take that deep staging, for example. A large portion of the film takes place in nondescript, dingy, dark rooms, but they are given an extraordinary charge of potential energy from the way that Tarkovsky and Yusov arrange shots to have bright, desperate close-ups crushing up against the camera, while other characters perform their business against in the depths, one half of the frame observing the other half while being conspicuously removed from being able to interact with it. Even better are the shots that make the background about space itself: the interiors have a curious way of feeling both very large and yet clearly boxed-in, in part because of how the depth makes us feel the presence of the walls. This makes the trips into the forest a staggering contrast, with the way that every row of trees seems to recede to an infinite point, coupled with the whiteness of the lighting, feeling almost overwhelmingly free and open.

If anything justifies those birch forest scenes, it's that feeling. Story-wise, the location is mostly associated with a frankly dull love triangle centered round the nurse Masha (Valentina Malyavina), who attracts the attentions of both the boyish Galtsev and the aggressive Capt. Kholin (Valentin Zubkov). It's a bit trite, and the performances in this subplot skew a little to close to the wooden earnestness of the kind of noble films about earnest peasants that had made much of Soviet cinema since the coming of sound feel a bit dopey and uninteresting. It's treated with admirably little sentiment - the hard lighting alone is enough to drain the saccharine quality from these scenes, but it feels too much of a war movie cliché, while also completely ignoring the much more compelling and troubling figure of Ivan himself.

That's where the film's heart is: making us feel horrible through the vessel of this broken non-child. There are only a couple of overt battle scenes in Ivan's Childhood, and they are wonderfully done, but the film is full of a sense of violence that's carried through its dark imagery, as well as the sharp, precise camera movements, and the crispness of the editing, as well as the story structure. Ivan himself is plagued by visions: some are clearly memories of his time with his mother (Irma Tarkovskaya, the director's then-wife), but others seem more like impressionistic fantasies of his memories. And at times, he simply seems overwhelmed by the misery of it all, and the film's present-tense reality twists expressionistically, or in one astonishing sequence, he's assaulted by horrific sounds of war that come only from his own anxiety. The memory sequences - something Tarkovsky would substantially develop in later films - provide a simple, clean contrast both to the gloom of the film and the ethereal hard whiteness of the forest, but they're cut in and out of the film with such abrupt, shocking contrasts in the picture and on the soundtrack, they can never become beatific or calming - they are deeply melancholy, even as they depict peace and family. Even at the end, when one of these visions is employed to give the film something that vaguely resembles a happy ending - after another little visionary sequence that's the bleakest part of the film, one that includes a truly draining shot of Burlyayev rolling over and over on the ground, as the camera, in close up, tries to keep up with him - has to end with a note of literal and figurative death and darkness.

So, a fun time, all in all. It is, at least one of the most apocalyptic anti-war films of its generation, using its dark images and implacable camera movement to suggest the war-torn nowhere that the film is set in is a place of constant hostility and danger. And its story takes the sturdy material of a young man, anxious to revenge himself on the bad guys that killed his family, and strips it of any patriotic romanticism by making the boy himself seem so alien and unrecognisable as a 12-year-old child, and by making his sacrifice seem so pointless by the time the movie ends. It's still the least grueling Tarkovsky feature, despite having the most urgent, immediate moral argument; but it's plenty heavy, one of the greatest anti-war films of the 1960s in part because it is so implacable and bleak.

*Russian cinema is, to my knowledge, the only national film industry that has for any period of time (in the 1900s and 1910s) pursued an explicit strategy of "all of our films need to be depressing and can't have even a trace of comedy" as a matter of product differentiation.