Shogun assassins

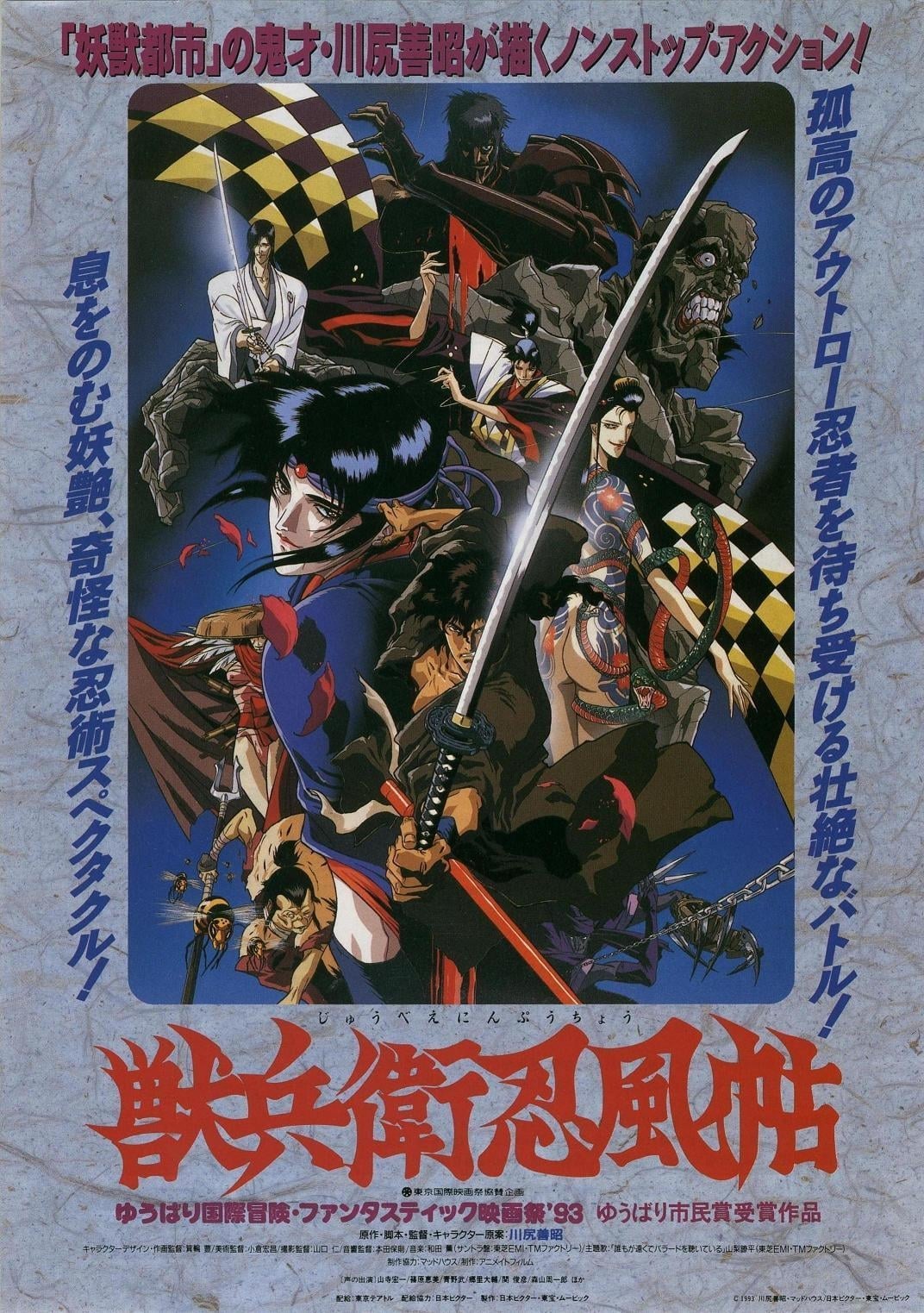

Back when Westerners had only the vaguest idea of what Japanese animation was all about, and the very notion of an animated film that was intended for an adults-only audience was unspeakably radical in and of itself, three movies were primarily responsible for introducing this bold new form of cinema to the world outside of East Asia. We are here to talk about the second of these, 1993's Ninja Scroll, written and directed by Kawajiri Yoshiaki, and produced by Animate Film. Neither the director nor the company has done very much in the intervening years - Kawajiri has directed the 2000 feature Vampire Hunter D: Bloodlust, a segment of 2003's The Animatrix, and a few television series, while the studio hasn't done much outside of OVA tie-ins for video game franchises - which is a frankly baffling fate for the creators of something this internationally successful. But really, it's not so different from the fate that has befallen Ninja Scroll itself. For while the other two of the Big 3 movies I started out by mentioning, 1988's Akira and 1995's Ghost in the Shell, have remained crucial touchstones, part of the "welcome to Japanese animation" starter park for any newcomer to the form a generation or more later, Ninja Scroll has lost some of its shine in later years. It hasn't tumbled into rank obscurity, or anything silly like that - I'd be surprised if any but the most casual anime fan hasn't at least heard of it - but it doesn't have the same cultural footprint as it did back in the '90s and early 2000s, and even then its cultural footprint was somewhat limited to "so there's this EXTREMELY VIOLENT cartoon..."

This is, I think, an injustice. To my way of thinking, Ninja Scroll is a genuinely great piece of animation, one of the medium's greatest achievements in the 1990s in any country. There have always been two criticisms that have dogged the film: first, that its violence, and particularly its sexual violence, is simply gratuitously shocking; second, that its story wouldn't hold up to a stiff breeze. As far as the former complaint goes, I suppose it's true, but it's true of every other chanbara (sword-fighting) movie made after 1970, and the great majority of them are not nearly this artful. As for the latter, no, I'm not having it at all. Ninja Scroll, it is true, has a fairly meager story, but rather than being a weakness, I think it's part and parcel of the film's great overriding strength, which is its deeply uncanny ability to feel like something eerily and wholly separate from any sort of grounded time and place.

I mean, it actually has a very specific time: the early Edo period in the first quarter of the 17th Century, when the Tokugawa shogunate had been established but before the Toyotomi clan, former rulers of Japan, had been completely rubbed out. But it doesn't feel historical in the slightest. It feels genuinely legendary, as though it comes riding in on a fog bank that drifts off the screen and surrounds the viewer, transporting us into a wholly mythic mode. A barely-formed sketch of a narrative in which a boldly-defined protagonist, wandering ninja mercenary Kibagami Jubei (Yamadera Koichi), does very little other than encounter and slay demons (or, often as not, survive to watch the demons killed by a stroke of extraordinary luck), and in so doing reluctantly defending the shogun against his enemies, feels exactly right in a way that something with carefully worked-out plot points happening to psychologically complex figures most likely wouldn't have.

This wonderful mood is, I suspect, entirely due to the film being animated. In broad terms, Ninja Scroll isn't very different from a great many '70s samurai films, but I've never seen one of those with this same uncanny feeling. That feeling is generated entirely through the absolutely gorgeous artwork used to bring the film to life - and let me say now, before I go into anything else, that Ninja Scroll is one of the handsomest animated films of its period. It has a graceful fluidity that's extremely uncommon in Japanese animation; as a cost-saving measure that graduated into a fully-fledged aesthetic, most of that country's animated output, then and now, favors limited movement and low frame rates, to create a style of somewhat stiff, jerky movement that, in the hands of the right artists, can be as expressive and rich as the priciest Disney animation. Or on the other hand, you can just go for it, and in large portions of Ninja Scroll, they're going for it. The film has several action sequences (it barely has anything else), and they have almost uniformly been treated with a smoothness that feels positively haunting, as characters glide and dart and slice their way through spaces.

So that's part of where the film's mood comes from: that too-smooth-to-be-real sense of everything being made out of liquid or mist, drifting around. Part of it comes from the exemplary lighting effects: damn near every new scene of Ninja Scroll seems to take place in some new environment rich in striking, evocative lighting, from a sunny bridge to a dusky bamboo forest that almost glows green to a gloomy lakeside that's heavy with the threat of rain. Eventually, it arrives at a sequence lit all in some impossible, unimaginable red, and if you pinned me down and asked me to name the single most striking-looking scene in all of '90s anime, I'm not sure if I could come up with a better candidate. And it still has a card left to play at that point, in the form of a raging fire illuminating the final battle.

And part of it comes from the illustrations of the backgrounds. Obviously, one of the reasons for loving Japanese animation is the succulent richness of the background paintings, but by any standards, Ninja Scroll is something special. The backgrounds here aren't going for realism, but they also aren't quite going for any traditional Japanese illustration styles that I know of; there's something softer and painterly that feels almost like there's a ghost of Impressionism hanging around in there someplace. The result is several spaces that feel complete and fleshed out, but have a distinct vagueness about them, something like a dream space rather than an actual location. It's maybe the most important way that the film sets a veil between itself and the viewer; this isn't actual Edo-period Japan, but a suggestion of it, based in shared fantasies about what might have been there if history was more like folklore.

And so we get back to the story, which has the headlong motivation of a dream or a folk tale, and the characters, who are all unabashedly types besides Jubei, there's Kagero (Shinohara Emi), who has carefully ingested so much poison that she has become toxic, and there's the shifty, toadlike Dakuan (Aono Takeshi), a Tokugawa spy who forces the other two to fight for him; and then there are the eight demons, each defined with some elaborate and modestly horrifying supernatural power, and these are themselves the excuse for some extraordinary feats of animation - gliding snake tattoos that come to life, balletic sword fighting moves, and so on. And they're also where the film's infamous violence shows up, and there really is something about seeing all this blood in animated form that makes it more distressing, somehow; but there's also something strikingly gorgeous in the graphic qualities of the brush strokes used to make blood spurt. It's body horror, but in the same abstract register as the rest of the film.

And that register really is all of it. Take this exact script, film it in live action, and sure, you probably end up with something cheesy, crass, and half-assed. And, to be absolutely certain, a hell of a lot of fun, unless your stony heart has no room for "a ninja fights eight demons in 94 minutes". But this isn't live action, and the dreamy pictorial richness imbued into it by its medium is hardly a secondary concern; it's the whole thing. And it's the reason that, more than a quarter century later, Ninja Scroll remains startling and shocking and brilliant.

This is, I think, an injustice. To my way of thinking, Ninja Scroll is a genuinely great piece of animation, one of the medium's greatest achievements in the 1990s in any country. There have always been two criticisms that have dogged the film: first, that its violence, and particularly its sexual violence, is simply gratuitously shocking; second, that its story wouldn't hold up to a stiff breeze. As far as the former complaint goes, I suppose it's true, but it's true of every other chanbara (sword-fighting) movie made after 1970, and the great majority of them are not nearly this artful. As for the latter, no, I'm not having it at all. Ninja Scroll, it is true, has a fairly meager story, but rather than being a weakness, I think it's part and parcel of the film's great overriding strength, which is its deeply uncanny ability to feel like something eerily and wholly separate from any sort of grounded time and place.

I mean, it actually has a very specific time: the early Edo period in the first quarter of the 17th Century, when the Tokugawa shogunate had been established but before the Toyotomi clan, former rulers of Japan, had been completely rubbed out. But it doesn't feel historical in the slightest. It feels genuinely legendary, as though it comes riding in on a fog bank that drifts off the screen and surrounds the viewer, transporting us into a wholly mythic mode. A barely-formed sketch of a narrative in which a boldly-defined protagonist, wandering ninja mercenary Kibagami Jubei (Yamadera Koichi), does very little other than encounter and slay demons (or, often as not, survive to watch the demons killed by a stroke of extraordinary luck), and in so doing reluctantly defending the shogun against his enemies, feels exactly right in a way that something with carefully worked-out plot points happening to psychologically complex figures most likely wouldn't have.

This wonderful mood is, I suspect, entirely due to the film being animated. In broad terms, Ninja Scroll isn't very different from a great many '70s samurai films, but I've never seen one of those with this same uncanny feeling. That feeling is generated entirely through the absolutely gorgeous artwork used to bring the film to life - and let me say now, before I go into anything else, that Ninja Scroll is one of the handsomest animated films of its period. It has a graceful fluidity that's extremely uncommon in Japanese animation; as a cost-saving measure that graduated into a fully-fledged aesthetic, most of that country's animated output, then and now, favors limited movement and low frame rates, to create a style of somewhat stiff, jerky movement that, in the hands of the right artists, can be as expressive and rich as the priciest Disney animation. Or on the other hand, you can just go for it, and in large portions of Ninja Scroll, they're going for it. The film has several action sequences (it barely has anything else), and they have almost uniformly been treated with a smoothness that feels positively haunting, as characters glide and dart and slice their way through spaces.

So that's part of where the film's mood comes from: that too-smooth-to-be-real sense of everything being made out of liquid or mist, drifting around. Part of it comes from the exemplary lighting effects: damn near every new scene of Ninja Scroll seems to take place in some new environment rich in striking, evocative lighting, from a sunny bridge to a dusky bamboo forest that almost glows green to a gloomy lakeside that's heavy with the threat of rain. Eventually, it arrives at a sequence lit all in some impossible, unimaginable red, and if you pinned me down and asked me to name the single most striking-looking scene in all of '90s anime, I'm not sure if I could come up with a better candidate. And it still has a card left to play at that point, in the form of a raging fire illuminating the final battle.

And part of it comes from the illustrations of the backgrounds. Obviously, one of the reasons for loving Japanese animation is the succulent richness of the background paintings, but by any standards, Ninja Scroll is something special. The backgrounds here aren't going for realism, but they also aren't quite going for any traditional Japanese illustration styles that I know of; there's something softer and painterly that feels almost like there's a ghost of Impressionism hanging around in there someplace. The result is several spaces that feel complete and fleshed out, but have a distinct vagueness about them, something like a dream space rather than an actual location. It's maybe the most important way that the film sets a veil between itself and the viewer; this isn't actual Edo-period Japan, but a suggestion of it, based in shared fantasies about what might have been there if history was more like folklore.

And so we get back to the story, which has the headlong motivation of a dream or a folk tale, and the characters, who are all unabashedly types besides Jubei, there's Kagero (Shinohara Emi), who has carefully ingested so much poison that she has become toxic, and there's the shifty, toadlike Dakuan (Aono Takeshi), a Tokugawa spy who forces the other two to fight for him; and then there are the eight demons, each defined with some elaborate and modestly horrifying supernatural power, and these are themselves the excuse for some extraordinary feats of animation - gliding snake tattoos that come to life, balletic sword fighting moves, and so on. And they're also where the film's infamous violence shows up, and there really is something about seeing all this blood in animated form that makes it more distressing, somehow; but there's also something strikingly gorgeous in the graphic qualities of the brush strokes used to make blood spurt. It's body horror, but in the same abstract register as the rest of the film.

And that register really is all of it. Take this exact script, film it in live action, and sure, you probably end up with something cheesy, crass, and half-assed. And, to be absolutely certain, a hell of a lot of fun, unless your stony heart has no room for "a ninja fights eight demons in 94 minutes". But this isn't live action, and the dreamy pictorial richness imbued into it by its medium is hardly a secondary concern; it's the whole thing. And it's the reason that, more than a quarter century later, Ninja Scroll remains startling and shocking and brilliant.

Categories: action, animation, fantasy, japanese cinema, men with swords, violence and gore