The bad seeds

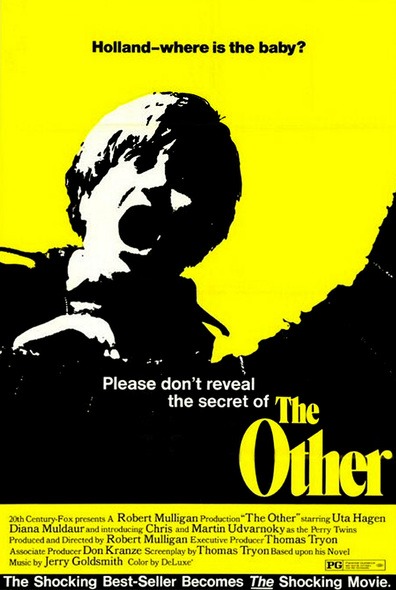

Above and beyond everything else, The Other is an exceptionally smart film. Not intelligent; smart. It does a superb job of manipulating and guiding its viewer, not just through Thomas Tryon's script (adapted from his own novel), but through the way it keeps dodging the stylistic norms of its genre. To look at the script, you'd say "ah, this is psychological horror", and it even is psychological horror, but it keeps acting like it's not, which makes it hard to adjust to the onslaught of horrific elements. In some ways, it feels like one of the several Depression-era dramas scattered across the New Hollywood Cinema, shot with a distinct sunny warmth by Robert Surtees, a three-time Oscar-winning cinematographer who would be high on the list for any producer making an early-20th Century costume drama in the early '70s. Not to mention that director Robert Mulligan is hardly the kind of person to push genre elements to the fore: he's best-known, undoubtedly for 1962's To Kill a Mockingbird, and that's fairly typical of his filmmaking style, which emphasises low-key moments of humans feeling their way around each other.

In short, The Other looks like a harmless, respectable movie, right up until it sinks its claws into you. In this, it is a perfect marriage of style and content, for we have in this film one of the finest examples I have seen of the evil child movie. And whatever else an evil child movie does, it presents a story of something cruel and vicious hiding in a blandly innocent form. So there's something cunning about the film following suit.

This particular example of the form happens to be an evil twin movie on top of it. Niles and Holland Perry (Chris and Martin Udvarnoky) are introduced to us in the midst of some mischief, and it's pretty much instantly clear what the dynamic is: Niles is the mild-mannered good one, Holland is the cunning one who can immediately get his brother to do whatever he wants. And in this case, it involve tormenting the next-door neighbor, Mrs. Rowe (Portia Nelson). Once we get just a flavor of how the boys interact, the film shifts over completely to mood and atmosphere for an entire act: we get to learn about the sprawling family that the boys are living in, here in the summer of 1935, on a farm that's being held together with just enough love and care that the worst of the Depression has been kept at bay. Their father has recently died, falling down the cellar stairs, leaving their mother Alexandra (Diana Muldaur) to keep mostly to herself in an upstairs bedroom; the main adult authority seems to be the boys' uncle George (Lou Frizzell) and his wife Vee (Norma Connolly), whose son Russell (Clarence Crow) is Niles and Holland's worst enemy in the world. Meanwhile, the boys' older sister Torrie (Jenny Sullivan) and her husband Rider (John Ritter) are expecting a baby, just to add to the clutter. As for Niles and Holland, they're most inclined towards their grandmother Ada (Uta Hagen), an immigrant from the Old World who has been instructing the boys in what she calls "the great game" - projecting their consciousness into nearby animals. And this turns out to include humans.

The family dynamic is messy enough that Niles and Holland are mostly able to spend their time alone an unsupervised, and this is where The Other starts to do its marvelous work. Initially, the film feels like a pure nostalgia trip, looking back to 1935 as a time of blithe innocence when boys could just go out and be boys. I am tempted to suggest that this is already the film's first and subtlest point of pulling the rug out from underneath us - for '35 was not after all as great a time as all that, and I wonder if the sunny happiness that superficially clings to the first act is meant to seem a bit hollow and ill-informed, in the face of the hardship that presumably go in to keeping the farm running. That might be giving it a bit too much credit, but it's undeniably the case that Mulligan and company are using nostalgia as a trick. As we'll find out pretty quickly, Holland's love of mischief goes deeper than boyish pranks, and when Russell dies in a horrible barn-related accident, not too long after catching the brothers admiring a ring that they're definitely not supposed to have - "it was supposed to be buried", we learn about this ring, enough times that it becomes very clear that the movie wants us to have a good long think about where it was supposed to be buried, and why it isn't there now - it's almost impossible not to suppose that Holland had a rather more active part in causing that to happen than even Niles can guess.

This happens fairly early in The Other, and it's no real surprise - we understand that we've entered some kind of thriller, Holland is instantly set up as the shiftiest character - and this is one of the other things the film does to astonishingly good effect: it lets us get ahead of the plot. I won't tell you where it goes, because any film this good and this obscure deserves to have an audience find it. I will tell you that it's not doing very much to hide where it goes - bizarrely little, in fact, given that it feels like there's a pretty big twist that's lazily spoiling itself for us way too far in advance. And this is part of what makes the film so damn smart. It's playing a magic trick on us, as sure as the one Holland plays on poor Mrs. Rowe after Russell's death, and with just as much malice in its heart. By letting us predict its first reveal, the film distracts us from the other reveals coming down the line - there are a good number of them, and every single one is more horrible and nasty-minded. I can't think of a way to actually say where the extraordinary power of The Other's last half-hour lies without giving too much away, but I think it's possible to say that the film, without stating it outright, lets us understand that "the great game" can be abused in a particularly horrifying way, and the effect that has on the brain of the abuser is maybe the most genuinely bone-chilling part of the film.

Underplaying that reveal is part of the film's overall strategy of never giving us the full brunt of its horror. The deaths in the film are all kept offscreen; we never see any of the things that end up causing so much distress and agony to the family. This isn't, I think, merely about tact. To be sure, not letting us see Russell impaled on a pitchfork probably has as much to do with Mulligan's tastes and 20th Century Fox's rules as with any strategy, but it works as part of the film's overall approach of not presenting itself as horror. Certainly, it's not an exploitation film of any stripe. It's that same Robert Surtees sunshiny thing: the visual mood is always that of a wistful memory, recalling a bygone generation when things were slower and simpler and had the texture of a faded photograph. And yet death is there, in all its rot and corruption. Unimaginable viciousness is there. New-fashioned '70s nihilism is there: it's giving away nothing at all to say that the film ends very nearly as unhappily as these plot ingredients could facilitate, in one of those peerless "evil won and good doesn't even have a plan B" final scenes that makes '70s horror some of the bleakest ever produced.

It is, in other words, a tough, brutal film. And it's somehow tougher and more brutal for simply presenting itself as the new film from the director of the previous year's Summer of '42 and a handsomely-mounted period drama about childhood in the Depression. It doesn't make its horrors digestible; they feel genuinely savage for showing up in such an unfussy, unshowy framework. That contrast between two different moods - the tones of the style and the overtones of the narrative - makes The Other a uniquely potent horror movie, one whose strongest horrors are the ones it leaves you to trip over yourself.

In short, The Other looks like a harmless, respectable movie, right up until it sinks its claws into you. In this, it is a perfect marriage of style and content, for we have in this film one of the finest examples I have seen of the evil child movie. And whatever else an evil child movie does, it presents a story of something cruel and vicious hiding in a blandly innocent form. So there's something cunning about the film following suit.

This particular example of the form happens to be an evil twin movie on top of it. Niles and Holland Perry (Chris and Martin Udvarnoky) are introduced to us in the midst of some mischief, and it's pretty much instantly clear what the dynamic is: Niles is the mild-mannered good one, Holland is the cunning one who can immediately get his brother to do whatever he wants. And in this case, it involve tormenting the next-door neighbor, Mrs. Rowe (Portia Nelson). Once we get just a flavor of how the boys interact, the film shifts over completely to mood and atmosphere for an entire act: we get to learn about the sprawling family that the boys are living in, here in the summer of 1935, on a farm that's being held together with just enough love and care that the worst of the Depression has been kept at bay. Their father has recently died, falling down the cellar stairs, leaving their mother Alexandra (Diana Muldaur) to keep mostly to herself in an upstairs bedroom; the main adult authority seems to be the boys' uncle George (Lou Frizzell) and his wife Vee (Norma Connolly), whose son Russell (Clarence Crow) is Niles and Holland's worst enemy in the world. Meanwhile, the boys' older sister Torrie (Jenny Sullivan) and her husband Rider (John Ritter) are expecting a baby, just to add to the clutter. As for Niles and Holland, they're most inclined towards their grandmother Ada (Uta Hagen), an immigrant from the Old World who has been instructing the boys in what she calls "the great game" - projecting their consciousness into nearby animals. And this turns out to include humans.

The family dynamic is messy enough that Niles and Holland are mostly able to spend their time alone an unsupervised, and this is where The Other starts to do its marvelous work. Initially, the film feels like a pure nostalgia trip, looking back to 1935 as a time of blithe innocence when boys could just go out and be boys. I am tempted to suggest that this is already the film's first and subtlest point of pulling the rug out from underneath us - for '35 was not after all as great a time as all that, and I wonder if the sunny happiness that superficially clings to the first act is meant to seem a bit hollow and ill-informed, in the face of the hardship that presumably go in to keeping the farm running. That might be giving it a bit too much credit, but it's undeniably the case that Mulligan and company are using nostalgia as a trick. As we'll find out pretty quickly, Holland's love of mischief goes deeper than boyish pranks, and when Russell dies in a horrible barn-related accident, not too long after catching the brothers admiring a ring that they're definitely not supposed to have - "it was supposed to be buried", we learn about this ring, enough times that it becomes very clear that the movie wants us to have a good long think about where it was supposed to be buried, and why it isn't there now - it's almost impossible not to suppose that Holland had a rather more active part in causing that to happen than even Niles can guess.

This happens fairly early in The Other, and it's no real surprise - we understand that we've entered some kind of thriller, Holland is instantly set up as the shiftiest character - and this is one of the other things the film does to astonishingly good effect: it lets us get ahead of the plot. I won't tell you where it goes, because any film this good and this obscure deserves to have an audience find it. I will tell you that it's not doing very much to hide where it goes - bizarrely little, in fact, given that it feels like there's a pretty big twist that's lazily spoiling itself for us way too far in advance. And this is part of what makes the film so damn smart. It's playing a magic trick on us, as sure as the one Holland plays on poor Mrs. Rowe after Russell's death, and with just as much malice in its heart. By letting us predict its first reveal, the film distracts us from the other reveals coming down the line - there are a good number of them, and every single one is more horrible and nasty-minded. I can't think of a way to actually say where the extraordinary power of The Other's last half-hour lies without giving too much away, but I think it's possible to say that the film, without stating it outright, lets us understand that "the great game" can be abused in a particularly horrifying way, and the effect that has on the brain of the abuser is maybe the most genuinely bone-chilling part of the film.

Underplaying that reveal is part of the film's overall strategy of never giving us the full brunt of its horror. The deaths in the film are all kept offscreen; we never see any of the things that end up causing so much distress and agony to the family. This isn't, I think, merely about tact. To be sure, not letting us see Russell impaled on a pitchfork probably has as much to do with Mulligan's tastes and 20th Century Fox's rules as with any strategy, but it works as part of the film's overall approach of not presenting itself as horror. Certainly, it's not an exploitation film of any stripe. It's that same Robert Surtees sunshiny thing: the visual mood is always that of a wistful memory, recalling a bygone generation when things were slower and simpler and had the texture of a faded photograph. And yet death is there, in all its rot and corruption. Unimaginable viciousness is there. New-fashioned '70s nihilism is there: it's giving away nothing at all to say that the film ends very nearly as unhappily as these plot ingredients could facilitate, in one of those peerless "evil won and good doesn't even have a plan B" final scenes that makes '70s horror some of the bleakest ever produced.

It is, in other words, a tough, brutal film. And it's somehow tougher and more brutal for simply presenting itself as the new film from the director of the previous year's Summer of '42 and a handsomely-mounted period drama about childhood in the Depression. It doesn't make its horrors digestible; they feel genuinely savage for showing up in such an unfussy, unshowy framework. That contrast between two different moods - the tones of the style and the overtones of the narrative - makes The Other a uniquely potent horror movie, one whose strongest horrors are the ones it leaves you to trip over yourself.

Categories: horror, new hollywood cinema, thrillers