"The fact that a person acted pursuant to order of his Government or of a superior does not relieve him from responsibility under international law, provided a moral choice was in fact possible to him."

Every single review of The Zone of Interest, the fourth feature film directed by Jonathan Glazer, at some point will reference the subtitle of Hannah Arendt's 1963 book Eichmann in Jerusalem: The Banality of Evil. Some reviews will mention it in the context of this being a very powerful illustration of Arendt's most famous idea. Some reviews will mention it as being proof that Arendt's thesis has long since gone stale. Some reviews will position the film as a counterpoint, that it challenges or complicates or even disproves Arendt. Some will bring it up very early. Some will bring it up late - maybe even so late as to make it seem like a secret reveal ("aha, it was the banality of evil all along!"). I brought it up in the very first sentence mostly so we could get it out of the way - now if it comes up again it will be natural, and not like I'm checking the Arendt box because That Is What Is Done.

As for why I have decided to burn an entire opening paragraph on explaining all of that, it's because writing about The Zone of Interest is already sort of meta-discursive, so might as well just acknowledge what we're doing here. To an extraordinarily unusual degree for a relatively mainstream film made in the anglosphere (despite a great majority of the film's dialogue being in German and a great majority of the film's cast being native-born in Germany, this is mostly a UK/US co-production), and to a degree that I believe is wholly unprecedented for films nominated for the Academy Award for Best Picture, this is a real proper Euro-style Art Film, the kind of thing that is designed strictly as an intellectual exercise and maybe, maybe you will get some conventional spectatorial pleasure out of it, but it doesn't seem like that was the artist's intent. And I don't, anyway, think there's any real spectatorial pleasure to be gotten out of The Zone of Interest. But the point is, this is the sort of thing designed to be written about first and foremost, to be discussed in cool, reflective conversations over post-movie dinner second, and perhaps at third, but certainly no higher, to be watched as a motion picture. Whether this is good or bad is sort of besides the point, though I do somewhat regret the film's Oscar attention, even though I'd certainly put it at the top of the pack of 2023 Best Picture nominees: not unlike The Tree of Life back in 2011, I suspect that part of the cost the film is going to pay for its visibility is that it's going to be watched by a lot of people who don't want it and aren't interested in it.

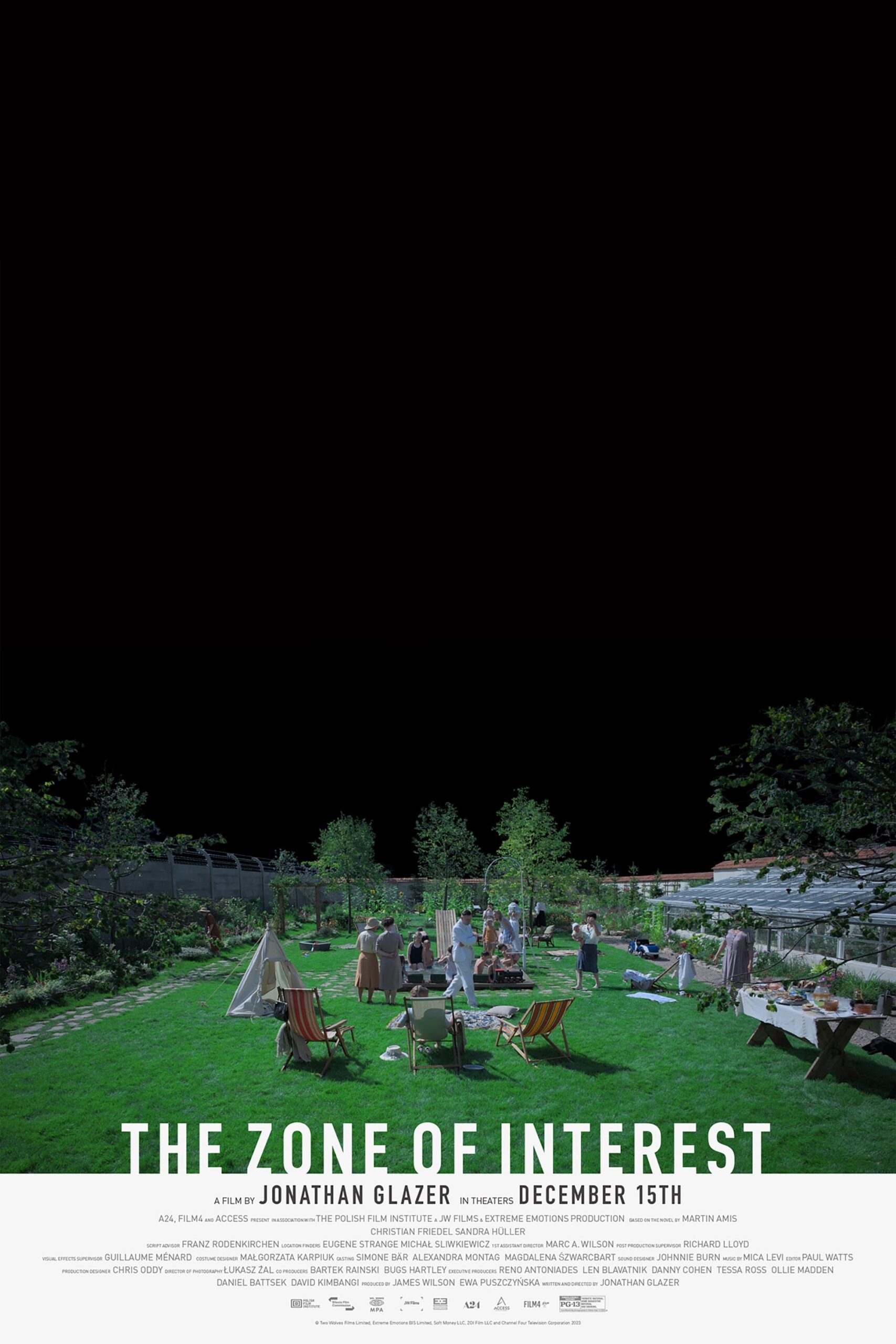

And now that I've burned a second paragraph, might as well make my own contribution to the Discourse. So, The Zone of Interest is the story of the German Höss family in 1943: father Rudolf (Christian Friedel), mother Hedwig (Sandra Hüller), and their five children. For the first 80 or so minutes of its 104-minute running time, it takes place exclusively in the house where the family lived at that time, or the large walled-in yard around that house; just on the other side of the wall is KL Auschwitz, the most infamous of the concentration camps used by Nazi Germany to house and exterminate political prisoners, mostly Polish Jews in this case (which part of the greater Auschwitz complex is just next door to the Hösses is a little unclear, intentionally so: the film is blurring the distinction between Auschwitz I and Auschwitz II-Birkenau, which were separated by a couple of miles). Rudolf is the commandant of the camp - the longest-serving commandant in the camp's history, in fact, with a total of four years and four months split between two periods between 1940 and 1945. And he was responsible for much of what has given "Auschwitz" such a looming presence in our cultural memory of World War II and the Holocaust, being one of the primary figures responsible for streamlining the camp's operations to make it the most efficient industrial-scale death factories in the history of the human species.

That's kind of all there is at the level of "plot" - The Zone of Interest isn't precisely a movie where "nothing happens", but it's awfully close, in part by being a movie where it's almost literally the case that nothing happens onscreen. Glazer's interest in tackling this project (ostensibly an adaptation of Martin Amis's 2014 novel of the same name, though my understanding is that the title, Auschwitz itself, and the presence of Hedwig Höss as a central character are pretty much all of the points of overlap) is rather blatantly because he wants to theorise about how we have depicted the Holocaust in drama and art between 1945 and 2023, which broadly speaking takes two parallel but I think meaningful distinct threads. One of these is to contemplate that phrase, "the banality of evil", and tussle with it a bit. I frankly don't know what Glazer thinks about the subject; he is carefully, meticulously laying out the movie as a series of ambiguities to nudge us towards asking questions on own (so, not even "just asking questions"), and letting us stew in them while we watch the movie spasm back and forth like a slowly-dying rat. And I would say that I like this very much. We have, in the 2020s, plenty of movies being made by people who obviously think the job of the artist is to provide moral dictation, and I hate the shit out of it. Glazer has never so obviously subscribed to the notion that the job of the artist is to unsettle and complicate and challenge, and then to leave things basically open-ended; he's creating a space for us to have a long, unpleasant think about the issues he's raising either directly or (far more often) from very slanted angles, and use the art object as a measuring stick for our own thoughts rather than an instruction manual. And as I walked out my own encounter with The Zone of Interest, what I landed on was, if I may be flippant about a desperately non-flippant movie, "which came first, the banality or the evil?"

In other words, what we're watching for most of the film is basically just the dreariest, most quotidian domestic stuff: the Höss family puttering around their dreadfully uninteresting days, in their weirdly artificial house whose interiors all scream "traditional German values" and whose exteriors all scream "inhuman concrete box". And the yard itself follows through, plopping little squares of plant life in geometrically cordoned-off regions of a huge rectangular space, beyond which the ominous buildings of the camp peek up. It is, in effect, watching people perform a simulacrum of domestic life in a simulacrum of a domestic space, in the literal shadow of the most efficient regime of murder ever designed. And so the film cannot possibly help but ask, "what kind of person would do such a thing?" And for this, it has no answer, none that it insists on. There are, I think, three main ways to examine the family: 1) boring, banal Germans who just want to have a nice little life of tasteless middlebrow coziness and will accept that they must live on the outer reaches of Hell in order to have it, because whatever, it's not like we're the ones being murdered, it's just "those people"; 2) cruel, vindictive, evil people who are primarily motivated by hatred and will happily arrange the widespread murder of the people they've either been told, or that they already believed, are preventing them from the pleasant banal lives that they dream of above all things; 3) incomprehensibly evil people about whom there is nothing whatsoever banal, and in fact banality is just the suit they wear when the guests come over, or when the Allies start to ask terribly inconvenient questions at a little happening they've put together in Nuremberg. Another way of looking at it: the film seems to ask, at certain times, "what would living in a place like this do to people? What would growing up here do to these children?" And sometimes it seems to ask, "what kind of people would choose to live in a place like this?" And sometimes and most darkly, it asks, "what kind of people would fabricate this place, so that they could then live there?"

So that's one reason I'm grateful to Glazer; he makes the space for these reflections and then leaves me to it. Somewhat paradoxically, the other reason I'm grateful, the other main thread of the film, is the aesthetic program he and his crew have put together for The Zone of Interest, and in this case there is no missing the loud, blunt declaration the movie is making, its extremely overt Message. Which isn't a new one, precisely, but it's being presented with exemplary skill: the images we have used to depict the Holocaust are insufficient. Moreover, they can only be insufficient. The Holocaust is too big for art; it can only be approached outside of art, or through anti-art. In other words, it can only be rendered as a conspicuous absence. This is the same line of reasoning that leads to the (extremely stylistically different) 1985 documentary Shoah, for one, and I will say that I don't know that I agree. Setting aside things like the 30-year-old argument about whether or not something like Schindler's List is immoral, I would not want to commit to any line of reasoning that would (it seems to me) take us to the point that we have to discard 1955's Night and Fog, which I still think is the greatest of all Holocaust film. But it doesn't matter: The Zone of Interest has its belief, and it is expressing it with great rigor. Glazer and his team, including cinematographer Łukasz Żal, editor Paul Watts, and sound designer Johnnie Burn, have committed to a particularly distinctive "anti-aesthetic", which needs to be in quotes for a reason; the goal to avoid "aestheticizing" evil things is kind of doomed from the start, because any time one makes an image out of a subject, that subject has necessarily become an aesthetic object. But, nevertheless, the style used in The Zone of Interest is studiously neutral, disaffected style, drained of all artistic excitement. Which is another way of saying: it's ugly, unpleasant, and choppy. Especially choppy, I might say; Glaze and Watts have executed an editing rhythm that is completely detached from the cadences of the dialogue, or the natural flow of dramatic scenes. Sometimes, it's motivated by where a character is standing relative to a doorway, so it jerks from room to room with the gracelessness of a mid-'90s video game where they hadn't figured out how to do camera controls in 3-D space yet. More often, it just seems to cut randomly and pointless, like there was a timer somewhere and it had to go to a new angle no matter right then no matter what else was happening. The result is a film that seems to lack all cinematic shaping, letting our attention wander aimlessly as these dull conversations bleed out. Żal's lighting flattens out spaces with no attention paid to continuity, draining the vitality from the colors even as they feel fully saturated, with the whole palette feeling like a collection of pastels. When the camera moves, it moves in rigid lateral lines, cold and tangibly mechanical. It's drab, drab and boring and spatially confusing, and then, atop this is laid the year's best sound mix, a curt mono soundtrack of the noises of gunshots and screams and God knows what vehicles grinding about that waft through the air and over the wall, indifferently mixing with the dialogue, sometimes burying it and sometimes not, nagging at us unpleasantly while seeming to affect the characters not at all.

There are some pointed exceptions to all of this, eruptions into the film's staid aesthetic where it feels like the we're-not-seeing of it gets overwhelmed by how disgusting these people are: night scenes of a Polish resistance operative smuggling apples to the camp, filmed in night vision with artificial monochrome, so we're seeing a horrible ghostly figure glowing white impossibly against the inky black night; a remarkable scene near the end where we finally do get to see the physical manifestation of the death camps, but done in a way that accuses the 21st Century of forgetting more than the 20th Century of perpetrating it in the first place; two pieces of music by Glazer's regular composer, Mica Levi, over the opening and closing credits, which are the only times the film ever engages the stereo channels or surrounds, so we're surrounded by the horribly accusing human voices of Levi's savage, tuneless music, surrounding us like a dark forest. At one point, the film just goes red - spontaneously, out of nowhere, slaps a bright red frame up. The only thing that connects these breaches of the deadened aesthetic is that they feel very, very violent to us who watch it, the places where the movie has to flare out with some kind of white-hot anger after being so careful to keep itself icy cold in its disgust for the Hösses, and maybe with us for being the kind of people who watch Holocaust prestige pictures. Like I said, I don't know that I agree with the film, but the film is making its argument well.

In fact, just about the only thing I don't like is the last long sequence; about 80 minutes in the Höss house, I said, but those next 15-ish minutes are just... I hesitate to call them a "mistake", since there's clearly intention behind them, but it's been a week since I saw the film, and I still don't know what this sequence achieve that couldn't have been achieved without preserving the dull claustrophobia of the rest of the movie. And look, I have just spent all these words describing a movie that has decided its main aesthetic priorities are to be unpleasant and boring to watch, aggressively unpleasant when it's not just being maddeningly repetitive and empty. And that's also very clearly intentional, and I think it works to make the film's case that these are awful, vicious people, and whether it's the banality of evil or the evil of banality that we're looking at, it doesn't deserve to be treated as anything but ugly and broken and distasteful by any standards that have ever registered as "beautiful" in any human aesthetic system. It works brilliantly, it's just that the thing it works brilliantly at is being an off-putting slog. And like I said at the start, the whole "thing" here is that you're obviously supposed to think about this and talk about it and write about it, and while you need to watch the movie to do those other things, it's not really "watchable". But that being said, I am extremely glad to have written about it.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

As for why I have decided to burn an entire opening paragraph on explaining all of that, it's because writing about The Zone of Interest is already sort of meta-discursive, so might as well just acknowledge what we're doing here. To an extraordinarily unusual degree for a relatively mainstream film made in the anglosphere (despite a great majority of the film's dialogue being in German and a great majority of the film's cast being native-born in Germany, this is mostly a UK/US co-production), and to a degree that I believe is wholly unprecedented for films nominated for the Academy Award for Best Picture, this is a real proper Euro-style Art Film, the kind of thing that is designed strictly as an intellectual exercise and maybe, maybe you will get some conventional spectatorial pleasure out of it, but it doesn't seem like that was the artist's intent. And I don't, anyway, think there's any real spectatorial pleasure to be gotten out of The Zone of Interest. But the point is, this is the sort of thing designed to be written about first and foremost, to be discussed in cool, reflective conversations over post-movie dinner second, and perhaps at third, but certainly no higher, to be watched as a motion picture. Whether this is good or bad is sort of besides the point, though I do somewhat regret the film's Oscar attention, even though I'd certainly put it at the top of the pack of 2023 Best Picture nominees: not unlike The Tree of Life back in 2011, I suspect that part of the cost the film is going to pay for its visibility is that it's going to be watched by a lot of people who don't want it and aren't interested in it.

And now that I've burned a second paragraph, might as well make my own contribution to the Discourse. So, The Zone of Interest is the story of the German Höss family in 1943: father Rudolf (Christian Friedel), mother Hedwig (Sandra Hüller), and their five children. For the first 80 or so minutes of its 104-minute running time, it takes place exclusively in the house where the family lived at that time, or the large walled-in yard around that house; just on the other side of the wall is KL Auschwitz, the most infamous of the concentration camps used by Nazi Germany to house and exterminate political prisoners, mostly Polish Jews in this case (which part of the greater Auschwitz complex is just next door to the Hösses is a little unclear, intentionally so: the film is blurring the distinction between Auschwitz I and Auschwitz II-Birkenau, which were separated by a couple of miles). Rudolf is the commandant of the camp - the longest-serving commandant in the camp's history, in fact, with a total of four years and four months split between two periods between 1940 and 1945. And he was responsible for much of what has given "Auschwitz" such a looming presence in our cultural memory of World War II and the Holocaust, being one of the primary figures responsible for streamlining the camp's operations to make it the most efficient industrial-scale death factories in the history of the human species.

That's kind of all there is at the level of "plot" - The Zone of Interest isn't precisely a movie where "nothing happens", but it's awfully close, in part by being a movie where it's almost literally the case that nothing happens onscreen. Glazer's interest in tackling this project (ostensibly an adaptation of Martin Amis's 2014 novel of the same name, though my understanding is that the title, Auschwitz itself, and the presence of Hedwig Höss as a central character are pretty much all of the points of overlap) is rather blatantly because he wants to theorise about how we have depicted the Holocaust in drama and art between 1945 and 2023, which broadly speaking takes two parallel but I think meaningful distinct threads. One of these is to contemplate that phrase, "the banality of evil", and tussle with it a bit. I frankly don't know what Glazer thinks about the subject; he is carefully, meticulously laying out the movie as a series of ambiguities to nudge us towards asking questions on own (so, not even "just asking questions"), and letting us stew in them while we watch the movie spasm back and forth like a slowly-dying rat. And I would say that I like this very much. We have, in the 2020s, plenty of movies being made by people who obviously think the job of the artist is to provide moral dictation, and I hate the shit out of it. Glazer has never so obviously subscribed to the notion that the job of the artist is to unsettle and complicate and challenge, and then to leave things basically open-ended; he's creating a space for us to have a long, unpleasant think about the issues he's raising either directly or (far more often) from very slanted angles, and use the art object as a measuring stick for our own thoughts rather than an instruction manual. And as I walked out my own encounter with The Zone of Interest, what I landed on was, if I may be flippant about a desperately non-flippant movie, "which came first, the banality or the evil?"

In other words, what we're watching for most of the film is basically just the dreariest, most quotidian domestic stuff: the Höss family puttering around their dreadfully uninteresting days, in their weirdly artificial house whose interiors all scream "traditional German values" and whose exteriors all scream "inhuman concrete box". And the yard itself follows through, plopping little squares of plant life in geometrically cordoned-off regions of a huge rectangular space, beyond which the ominous buildings of the camp peek up. It is, in effect, watching people perform a simulacrum of domestic life in a simulacrum of a domestic space, in the literal shadow of the most efficient regime of murder ever designed. And so the film cannot possibly help but ask, "what kind of person would do such a thing?" And for this, it has no answer, none that it insists on. There are, I think, three main ways to examine the family: 1) boring, banal Germans who just want to have a nice little life of tasteless middlebrow coziness and will accept that they must live on the outer reaches of Hell in order to have it, because whatever, it's not like we're the ones being murdered, it's just "those people"; 2) cruel, vindictive, evil people who are primarily motivated by hatred and will happily arrange the widespread murder of the people they've either been told, or that they already believed, are preventing them from the pleasant banal lives that they dream of above all things; 3) incomprehensibly evil people about whom there is nothing whatsoever banal, and in fact banality is just the suit they wear when the guests come over, or when the Allies start to ask terribly inconvenient questions at a little happening they've put together in Nuremberg. Another way of looking at it: the film seems to ask, at certain times, "what would living in a place like this do to people? What would growing up here do to these children?" And sometimes it seems to ask, "what kind of people would choose to live in a place like this?" And sometimes and most darkly, it asks, "what kind of people would fabricate this place, so that they could then live there?"

So that's one reason I'm grateful to Glazer; he makes the space for these reflections and then leaves me to it. Somewhat paradoxically, the other reason I'm grateful, the other main thread of the film, is the aesthetic program he and his crew have put together for The Zone of Interest, and in this case there is no missing the loud, blunt declaration the movie is making, its extremely overt Message. Which isn't a new one, precisely, but it's being presented with exemplary skill: the images we have used to depict the Holocaust are insufficient. Moreover, they can only be insufficient. The Holocaust is too big for art; it can only be approached outside of art, or through anti-art. In other words, it can only be rendered as a conspicuous absence. This is the same line of reasoning that leads to the (extremely stylistically different) 1985 documentary Shoah, for one, and I will say that I don't know that I agree. Setting aside things like the 30-year-old argument about whether or not something like Schindler's List is immoral, I would not want to commit to any line of reasoning that would (it seems to me) take us to the point that we have to discard 1955's Night and Fog, which I still think is the greatest of all Holocaust film. But it doesn't matter: The Zone of Interest has its belief, and it is expressing it with great rigor. Glazer and his team, including cinematographer Łukasz Żal, editor Paul Watts, and sound designer Johnnie Burn, have committed to a particularly distinctive "anti-aesthetic", which needs to be in quotes for a reason; the goal to avoid "aestheticizing" evil things is kind of doomed from the start, because any time one makes an image out of a subject, that subject has necessarily become an aesthetic object. But, nevertheless, the style used in The Zone of Interest is studiously neutral, disaffected style, drained of all artistic excitement. Which is another way of saying: it's ugly, unpleasant, and choppy. Especially choppy, I might say; Glaze and Watts have executed an editing rhythm that is completely detached from the cadences of the dialogue, or the natural flow of dramatic scenes. Sometimes, it's motivated by where a character is standing relative to a doorway, so it jerks from room to room with the gracelessness of a mid-'90s video game where they hadn't figured out how to do camera controls in 3-D space yet. More often, it just seems to cut randomly and pointless, like there was a timer somewhere and it had to go to a new angle no matter right then no matter what else was happening. The result is a film that seems to lack all cinematic shaping, letting our attention wander aimlessly as these dull conversations bleed out. Żal's lighting flattens out spaces with no attention paid to continuity, draining the vitality from the colors even as they feel fully saturated, with the whole palette feeling like a collection of pastels. When the camera moves, it moves in rigid lateral lines, cold and tangibly mechanical. It's drab, drab and boring and spatially confusing, and then, atop this is laid the year's best sound mix, a curt mono soundtrack of the noises of gunshots and screams and God knows what vehicles grinding about that waft through the air and over the wall, indifferently mixing with the dialogue, sometimes burying it and sometimes not, nagging at us unpleasantly while seeming to affect the characters not at all.

There are some pointed exceptions to all of this, eruptions into the film's staid aesthetic where it feels like the we're-not-seeing of it gets overwhelmed by how disgusting these people are: night scenes of a Polish resistance operative smuggling apples to the camp, filmed in night vision with artificial monochrome, so we're seeing a horrible ghostly figure glowing white impossibly against the inky black night; a remarkable scene near the end where we finally do get to see the physical manifestation of the death camps, but done in a way that accuses the 21st Century of forgetting more than the 20th Century of perpetrating it in the first place; two pieces of music by Glazer's regular composer, Mica Levi, over the opening and closing credits, which are the only times the film ever engages the stereo channels or surrounds, so we're surrounded by the horribly accusing human voices of Levi's savage, tuneless music, surrounding us like a dark forest. At one point, the film just goes red - spontaneously, out of nowhere, slaps a bright red frame up. The only thing that connects these breaches of the deadened aesthetic is that they feel very, very violent to us who watch it, the places where the movie has to flare out with some kind of white-hot anger after being so careful to keep itself icy cold in its disgust for the Hösses, and maybe with us for being the kind of people who watch Holocaust prestige pictures. Like I said, I don't know that I agree with the film, but the film is making its argument well.

In fact, just about the only thing I don't like is the last long sequence; about 80 minutes in the Höss house, I said, but those next 15-ish minutes are just... I hesitate to call them a "mistake", since there's clearly intention behind them, but it's been a week since I saw the film, and I still don't know what this sequence achieve that couldn't have been achieved without preserving the dull claustrophobia of the rest of the movie. And look, I have just spent all these words describing a movie that has decided its main aesthetic priorities are to be unpleasant and boring to watch, aggressively unpleasant when it's not just being maddeningly repetitive and empty. And that's also very clearly intentional, and I think it works to make the film's case that these are awful, vicious people, and whether it's the banality of evil or the evil of banality that we're looking at, it doesn't deserve to be treated as anything but ugly and broken and distasteful by any standards that have ever registered as "beautiful" in any human aesthetic system. It works brilliantly, it's just that the thing it works brilliantly at is being an off-putting slog. And like I said at the start, the whole "thing" here is that you're obviously supposed to think about this and talk about it and write about it, and while you need to watch the movie to do those other things, it's not really "watchable". But that being said, I am extremely glad to have written about it.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.