Days of Malick: You can only be happy if you love. Unless you love, your life will flash by.

An older review of this film can be found here.

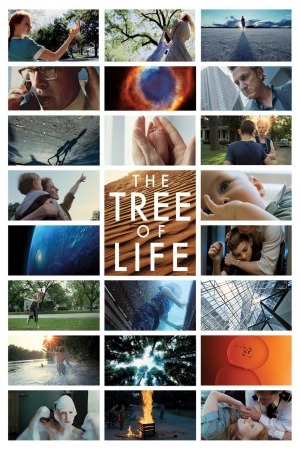

It is not demanding more of The Tree of Life than it can withstand to call it the defining film of Terrence Malick's whole life. From the moment he first began drafting the script to what was then called Q, in 1978, it was fully 33 years before the last edits were locked down and the film premiered to the most prestigious prize of the director's career, the 2011 Palme d'Or at Cannes. It is the film that most baldly and perhaps desperately states the questions that have in some way informed all of his work: what is our nature as spiritual beings, how can we commune with something larger than ourselves, and how can we be perfect if the universe around us is so full of brokenness and unanswered yearning? It considers with a frankness unheard of in American narrative cinema the identity of God in a universe that cannot possibly be ruled by an omnipotent, benevolent creator, based on the evidence we can see. It recalls, obviously, Tarkovsky; I personally can't help but see quite a bit of Stan Brakhage in there too, and if I've just made the most obvious "avant-garde filmmaker with a fixation on the cosmic and spiritual" reference in the world, I will freely admit to my intensely limited exposure to avant-garde cinema.

The first thing we see of the movie, after a single card quoting from the Book of Job (this is Malick's first film to delay the declaration of its title until the end credits), is a blurry, flowing shape, a smack of orange and yellow and blue ephemera in the middle of total blackness. It somewhat resembles an aurora; I have grown attached to thinking of it as what a baby sees when it is in the womb. After a long, lingering stretch of this image, the film leaps into Waco, Texas, in the 1950s, where a woman (Jessica Chastain) watches her children - she is given no name during the course of the movie, though the credits identify her as Mrs. O'Brien. Over disconnected shots of quiet suburban bliss, enjoying the soft light of late afternoon in a neighborhood of single family houses, the woman speaks the first words of the film, in voiceover, of course (as the defining film of Terrence Malick's life must undoubtedly be heavily invested in voiceover): she identifies that all humans must at some time choose between the way of nature and the way of grace.

This startled me a little, the first time I saw the movie: if Malick's cinema as a whole is about one single thing, it is about the inseparability of nature and grace, wouldn't you say? (Also, the first time I saw the movie, the projection was fucked up and hadn't quite gotten fixed by this point, so I had other things on my mind than the niceties of expression in the writing). "Nature", though, does not here mean the natural world, but human nature; the woman glides right into the explanation of her words, explaining that those who follow the way of nature are driven to shut out goodness and light, to force themselves and other into a spiraling mess of proving themselves the strongest, ablest, richest, most powerful, etc. etc. Those who follow the way of grace simply allow themselves to Be: that's not the exact way she puts it, "to Be", but you can be damn sure from her tone that if she did use those precise words, "Be" would get capitalised like a sumbitch.

The Tree of Life will spent a great deal of time examining the gulf between the way of nature and the way of grace; but that is hardly the only thing it spends time doing. One does not give a film that title without intending that it have some measure of thematic ambition to it.

There comes a point in all its languid, exquisite shots of Eisenhower-era Waco, when the film jumps forward ten years or more; it does not flag our attention to this fact, unless it be that Mrs. O'Brien's husband (Brad Pitt) looks a touch older around the eyes, and that the couple lives in a different house, one that is airy and more open and dominated by large windows; it is glossier and grander but less livable, feeling more of a model than a real home. It is here that the O'Briens receive bad news in the form of a Western Union telegram, and here also that we leave them to their grief, jumping forward again to find their eldest son, Jack (Sean Penn) - Jack is the only character ever given a name onscreen, for the good reason that it more or less concerns his perceptions - grown up and living in the city and being very moody. It is from him that we learn that the bad news was the death of the middle son, R.L.

Jack works in a tall office building, shiny and splendid and cold; the increased presence of glass windows in this film is directly correlated with how inhuman the building in question is (Jack is also an architect, a fact you can just barely scrape out of the evidence presented onscreen if you knew it to begin with). As he tells his father on the phone, Jack thinks of his dead brother every day, and this day will push him even deeper into reverie than usual: for right outside his glossy, overwhelming building, a new tree is being planted: and this tree triggers in his mind all the trees that have been important in his life - the tree his father planted when he was a toddler, the tree he and his brothers and mother would swing from, the trees dominating the mostly undeveloped landscape of Waco - and he lapses into a stream of memories: first disconnected, elliptically centering around R.L. (Laramie Eppler), gradually landing upon himself as a child (Hunter McCracken), and his youngest brother (Tye Sheridan), and his parents.

If we want to be straightforward about one of the most diabolically unstraightforward movies to get a major American release in years, the bulk The Tree of Life is Jack's memories of the summer when he was 11 years old, all of it relived as he ascends in an elevator. There's merit to that reading: young Jack is plainly the figure through which the rest of the narrative is viewed, and the elliptical structure of the film mimics memory in much the same way that the unconventional structure of the director's immediately preceding feature, The New World, may have been designed to evoke the dreamer's perception of being in a dream: though the scenes in Waco appear to move chronologically, they do not subscribe to any rational system of causality or continuity, instead focusing on emotionally resonant moments that would tend to stand out, 40 years later, as the key moments of a single summer, even if they do not often have anything to do with one another (of The Tree of Life's five editors, two - Hank Corwin and Mark Yoshikawa - also performed that duty in The New World, and if pressed I would say that these two films bear more similarity in their editing than they do to any of Malick's other work). Particularly, in the first part of the movie, the scenes collide with one another in a manner that can perhaps only be explained as the free association of a mind that has already been triggered to think about Those Days and That Dead Brother, aimlessly darting from one fragment to another.

At the same time, The Tree of Life cannot be entirely explained as Jack's memories: for as his voiceover drifts from one musing to another, it becomes intermingled with that of his mother, back in the 1960s, when she received the news of her son's death, and we return to those terrible moments; for a brief scene or two, it appears that Malick is going for straight-up misery porn, dwelling in the awful, empty moment of feeling that there is nothing that means anything and no joy nor grace. In her despair, Mrs. O'Brien challenges God, softly, almost as though her defiance was a prayer: "where were you?" It is the riposte to that quote from Job which opens the movie: "Where were you when I laid the foundations of the earth... While the morning stars sang together and all the sons of God shouted for joy?" Then that swirling, amorphous pre-birth image returns - though The Tree of Life lacks a "theme song" in the way that all of Malick's previous films do, it strikes me that this image serves the same structural role, appearing at the beginning and end of the movie, and then at a single important moment of the movie - and we see what laying the foundations of the earth looks like.

The Creation of the Universe sequence was legendary before a single audience member had ever laid eyes on The Tree of Life, and it damn well ought to have been: there's audacity and then there's audacity. In a combination of practical effects and CGI used as minimally as possible, we see the coalescence of energy into matter and gaseous matter into solids, and into liquid, and the formation of the Earth in fire and stress, and the bubbles of Darwin's "little warm pond" where life began. We see cells and we see the primitive, shapeless jellyfish, animals thought to exist in much the same shape now as they did at the dawn of the fossil record; we see pleiosaurs and dinosaurs. I previously compared this sequence to the "Beyond the Infinite" chapter from Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey, in no small part because visual effects guru Douglas Trumbull was involved with both; I'll stand behind that, on the grounds that they are two of the most challenging, experimental sequences ever executed in an American narrative film, though I find I should qualify that comparison: they are, after all, representing polar opposites, the origin of existence versus the great leap into whatever comes after anything we know to call "existence".

Clipped aside from the film in which it occurs, this sequence is so beautiful that it's frankly not fair: certain visual concepts repeat themselves over and over again, most obviously a blue and orange nebula that is framed to look exactly like a blue and orange hot spring that is framed to look exactly like some blue and orange chemical process within the human genes. Several of the images are further repeated in the movie to come, though I did say we were clipping it out, didn't I? Shame on me.

It is a glorious, dramatic, frankly religious experience: it is Malick's attempt to find the mind of God and explore it, and he does so in such a way that The Tree of Life itself is both cathedral and sermon. And yet, this is not at all the simple act of glory it seems like. The pounding, immense piece of music that begins this sequence is the "Lacrimosa" from Zbigniew Preisner's Requiem for My Friend - noted spiritual filmmaker Krzysztof Kieślowski being the friend - and while it is clearly a liturgical piece, one needn't know that lacrimosa is the Latin for "defined by or causing a tearful state", or that the word is typically used to describe a particularly mournful movement in a requiem mass, to recognise that the sound of it is rather more dolorous than triumphal: here, the point seems to be that the act of creation is an inherently painful one, full of destruction (there are many images of fire in this sequence) and strife. We see the asteroid that wiped out most life at the K-T boundary. The much-anticipated dinosaurs are haunted by death: the pleiosaur is bleeding out of a hideous gash, one dinosaur looks around like a nervous cat, another is about to be devoured by a predator until something in its feeble beatings inspires some deep, primitive measure of pity.

And that is the flipside: there is mercy in the act of creation as well, for all creation is a gift. Violence is nature; generosity is grace.

Having taken us from the Big Bang to the version of Earth we know and love, The Tree of Life repeats this process on a far smaller scale. Mrs. O'Brien is pregnant, her stomach resembling the disc of Jupiter spotted earlier in the film, and for several minutes we watch as her three boys are born and grow to become preteens. By giving the same space in the movie to each of these disparate sequences (though the "youth in Waco" scenes are scored with infinitely lighter, more celebratory music), Malick invites us to understand how the birth and life of a child is situated within the birth and life of a universe: though we humans are an infinitesimally small component of the place we inhabit, we are still a component, and like it, we are miracles of creation.

In truth, it's this sequence that I like best in the whole movie: maybe because it is the most comforting, maybe because it is the sweetest. The shot of toddler Jack regarding infant R.L. with a supremely dubious look is, to me, one of the most exquisite moments in all of Malick's cinema.

It's only now, after some 40 minutes, that the "real film" actually starts: a delicate fable of life in a small town that boasts the most intimate, human-sized drama of anything Malick's done since his two '70s films, Badlands and Days of Heaven (I find it fascinating, and almost totally useless, that all of his works since his 20-year sabbatical ended in 1998 have started with the word "The", while neither of his first films did*). Jack is right at the cusp of adolescence, and starting to chafe under his father's lopsided, domineering, "white male in the '50s" attitude, while clinging to his mother and her ethereal femininity, the very embodiment of grace. Tiny moments abound, some of them troubling in their metaphoric overtones (Jack steals a neighbor's slip and then tosses it in a river, watching it float away), some heartbreaking (Jack's guilt over being party to a "game" of exploding a frog on a rocket; I like to think this was Malick's intentional nod to Lynne Ramsay's Ratcatcher, in recognition of her references to Badlands and Days of Heaven in that feature), some beautiful as nearly all the scenes of the three brothers goofing about. At least one brilliant moment is a combination of all of the above, as Jack enviously watches his father and R.L. - the one who dies, and who as a child looks so like Brad Pitt it's uncanny - noodling around with musical instruments (this sequence does all sorts of extra duty: it shows the middle child as inheriting the father's musical skill, but also the mother's sensitivity; while Jack, already aware, perhaps, that he is truly the son of his father despite his greater love for his mother, can do nothing but seethe).

The film is pleasurable in no small part because of its extremely specific observation: the moment-to-moment recreation of life in a certain place in a certain time (Malick, who grew up in Waco, would have been about Jack's age in the film's period), the details of family life, and the sharp depiction of its characters. Never before an actor of children, Malick nevertheless got a deep, wounded, yearning performance from McCracken, never asking him to embody an idea of American boyhood but always play this boy's impressions of this moment. Pitt's depiction of a barking man who wants to be better than he is is absolutely devastating: the way his face shows that he wishes, badly, to show his sons that he loves him, but cannot; the scene where he confronts the gap separating him from his fantasy of what he'd be able to accomplish, having been caught in a plant closing, is all the more heartbreaking since for so much of the movie we've been spotting the sensitive, bruised man hiding beneath the culturally-enforced shell, only to finally break in a far more tragic version of Col. Tall's "I've eaten untold buckets of shit" rant from The Thin Red Line.

Best in show, though, no doubt about it, is Chastain, the latest in Malick's storied career of promoting nobodies to prominent roles and seeing his gamble pay dividends: Sissy Spacek and Martin Sheen, Brooke Adams and Sam Shepard, Jim Caviezel and Ben Chaplin, Q'orianka Kilcher. It cannot have been fun to play a character who ends up, in the final cut, representing Womanhood, Spirituality, the Mother Goddess, and all that, and still make her come across as a breathing, thinking person; Chastain does this.

Even considering all this, The Tree of Life is so much more than a family drama, a familiar story told with uncommon beauty and skill. It is an attempt to grapple with the meaning of life and God and all: in its allusions to Job, it admits to asking the hoary old question, "if God is good, why is life so full of suffering?"; the relationship between the O'Briens is unmistakably a metaphor for the conflict between the traditional Abrahamic God as merciless patriarchal overlord and the more humanist, liberal Christianity tradition that sees God as the state of joy and bliss and total love. I don't think it's overreaching at all to suggest that adult Jack's skyscraper is framed so that it does not just reflect the sky "where God lives", as his mother once said; it indeed reaches up to heaven, trying to shorten the distance between man and God, not in the grasping, selfish way of the Tower of Babel, but out of desperate need to find solace in an world that offers none of it. Images that simply point the camera up and gawk at the heavens are almost as common in The Tree of Life as silken steadicam shots or dusky interiors - Emmanuel Lubezki, the first cinematographer to ever pull a second tour of duty with Malick, certainly nails all the warmth of his locations and shows how easily warmth can turn stifling and suffocating, once again as in The New World using little to no artificial light, and using the encroaching dusk to turn the simplest shots into visual poetry of the highest order - and the film palpably wants to pull God to it, to look God in the face, and ask without judgment, only whole-hearted curiosity, "Why?" The climactic sequence, in which adult Jack has a vision of happiness - call it Heaven, but the film does not - may be a bridge too far in terms of kitschey religious symbolism (I do not know my opinion on the matter, not yet), but it cannot be said to lack the courage of conviction. And I want to point out that Jack has this vision in the highest point of his skyscraper.

Here is how I know that The Tree of Life is a masterpiece: it does all of these things, and touches me so much that I can barely stand it, and there is basically not one single element in the film that speaks to me personally. I have no siblings, and cannot begin to speak to the veracity of the brotherly relationships that lend the film its most poignant and magical moments; I've didn't grow up in the kind of neighborhood where you could run around and stumble across wonderful things every which where; I have never had an acrimonious relationship with my father; I find the very idea of spotting Infinite Motherhood to be uncomfortably "othering" of women. And most crucially of all, I'm enough of a doctrinaire atheist that the questions, "Who is God? What is God thinking? How do we become closer to God?" are inherently as useful and compelling as wondering why we can't taste our own tongue. And despite all of these handicaps, the movie still feels like it's holding up a mirror: and it presents its intently specific story with such universal artistry and beauty and, yes, grace, that I cannot help but be swept up by it: twice I have seen the movie, and twice the moment that it ended felt like being violently shaken awake. I have now, twice, greeted the end of the movie with deep exhalation of feeling that reaches down into my toes, not sure if I should dance or cry from the unutterable glory of it.

It is not demanding more of The Tree of Life than it can withstand to call it the defining film of Terrence Malick's whole life. From the moment he first began drafting the script to what was then called Q, in 1978, it was fully 33 years before the last edits were locked down and the film premiered to the most prestigious prize of the director's career, the 2011 Palme d'Or at Cannes. It is the film that most baldly and perhaps desperately states the questions that have in some way informed all of his work: what is our nature as spiritual beings, how can we commune with something larger than ourselves, and how can we be perfect if the universe around us is so full of brokenness and unanswered yearning? It considers with a frankness unheard of in American narrative cinema the identity of God in a universe that cannot possibly be ruled by an omnipotent, benevolent creator, based on the evidence we can see. It recalls, obviously, Tarkovsky; I personally can't help but see quite a bit of Stan Brakhage in there too, and if I've just made the most obvious "avant-garde filmmaker with a fixation on the cosmic and spiritual" reference in the world, I will freely admit to my intensely limited exposure to avant-garde cinema.

The first thing we see of the movie, after a single card quoting from the Book of Job (this is Malick's first film to delay the declaration of its title until the end credits), is a blurry, flowing shape, a smack of orange and yellow and blue ephemera in the middle of total blackness. It somewhat resembles an aurora; I have grown attached to thinking of it as what a baby sees when it is in the womb. After a long, lingering stretch of this image, the film leaps into Waco, Texas, in the 1950s, where a woman (Jessica Chastain) watches her children - she is given no name during the course of the movie, though the credits identify her as Mrs. O'Brien. Over disconnected shots of quiet suburban bliss, enjoying the soft light of late afternoon in a neighborhood of single family houses, the woman speaks the first words of the film, in voiceover, of course (as the defining film of Terrence Malick's life must undoubtedly be heavily invested in voiceover): she identifies that all humans must at some time choose between the way of nature and the way of grace.

This startled me a little, the first time I saw the movie: if Malick's cinema as a whole is about one single thing, it is about the inseparability of nature and grace, wouldn't you say? (Also, the first time I saw the movie, the projection was fucked up and hadn't quite gotten fixed by this point, so I had other things on my mind than the niceties of expression in the writing). "Nature", though, does not here mean the natural world, but human nature; the woman glides right into the explanation of her words, explaining that those who follow the way of nature are driven to shut out goodness and light, to force themselves and other into a spiraling mess of proving themselves the strongest, ablest, richest, most powerful, etc. etc. Those who follow the way of grace simply allow themselves to Be: that's not the exact way she puts it, "to Be", but you can be damn sure from her tone that if she did use those precise words, "Be" would get capitalised like a sumbitch.

The Tree of Life will spent a great deal of time examining the gulf between the way of nature and the way of grace; but that is hardly the only thing it spends time doing. One does not give a film that title without intending that it have some measure of thematic ambition to it.

There comes a point in all its languid, exquisite shots of Eisenhower-era Waco, when the film jumps forward ten years or more; it does not flag our attention to this fact, unless it be that Mrs. O'Brien's husband (Brad Pitt) looks a touch older around the eyes, and that the couple lives in a different house, one that is airy and more open and dominated by large windows; it is glossier and grander but less livable, feeling more of a model than a real home. It is here that the O'Briens receive bad news in the form of a Western Union telegram, and here also that we leave them to their grief, jumping forward again to find their eldest son, Jack (Sean Penn) - Jack is the only character ever given a name onscreen, for the good reason that it more or less concerns his perceptions - grown up and living in the city and being very moody. It is from him that we learn that the bad news was the death of the middle son, R.L.

Jack works in a tall office building, shiny and splendid and cold; the increased presence of glass windows in this film is directly correlated with how inhuman the building in question is (Jack is also an architect, a fact you can just barely scrape out of the evidence presented onscreen if you knew it to begin with). As he tells his father on the phone, Jack thinks of his dead brother every day, and this day will push him even deeper into reverie than usual: for right outside his glossy, overwhelming building, a new tree is being planted: and this tree triggers in his mind all the trees that have been important in his life - the tree his father planted when he was a toddler, the tree he and his brothers and mother would swing from, the trees dominating the mostly undeveloped landscape of Waco - and he lapses into a stream of memories: first disconnected, elliptically centering around R.L. (Laramie Eppler), gradually landing upon himself as a child (Hunter McCracken), and his youngest brother (Tye Sheridan), and his parents.

If we want to be straightforward about one of the most diabolically unstraightforward movies to get a major American release in years, the bulk The Tree of Life is Jack's memories of the summer when he was 11 years old, all of it relived as he ascends in an elevator. There's merit to that reading: young Jack is plainly the figure through which the rest of the narrative is viewed, and the elliptical structure of the film mimics memory in much the same way that the unconventional structure of the director's immediately preceding feature, The New World, may have been designed to evoke the dreamer's perception of being in a dream: though the scenes in Waco appear to move chronologically, they do not subscribe to any rational system of causality or continuity, instead focusing on emotionally resonant moments that would tend to stand out, 40 years later, as the key moments of a single summer, even if they do not often have anything to do with one another (of The Tree of Life's five editors, two - Hank Corwin and Mark Yoshikawa - also performed that duty in The New World, and if pressed I would say that these two films bear more similarity in their editing than they do to any of Malick's other work). Particularly, in the first part of the movie, the scenes collide with one another in a manner that can perhaps only be explained as the free association of a mind that has already been triggered to think about Those Days and That Dead Brother, aimlessly darting from one fragment to another.

At the same time, The Tree of Life cannot be entirely explained as Jack's memories: for as his voiceover drifts from one musing to another, it becomes intermingled with that of his mother, back in the 1960s, when she received the news of her son's death, and we return to those terrible moments; for a brief scene or two, it appears that Malick is going for straight-up misery porn, dwelling in the awful, empty moment of feeling that there is nothing that means anything and no joy nor grace. In her despair, Mrs. O'Brien challenges God, softly, almost as though her defiance was a prayer: "where were you?" It is the riposte to that quote from Job which opens the movie: "Where were you when I laid the foundations of the earth... While the morning stars sang together and all the sons of God shouted for joy?" Then that swirling, amorphous pre-birth image returns - though The Tree of Life lacks a "theme song" in the way that all of Malick's previous films do, it strikes me that this image serves the same structural role, appearing at the beginning and end of the movie, and then at a single important moment of the movie - and we see what laying the foundations of the earth looks like.

The Creation of the Universe sequence was legendary before a single audience member had ever laid eyes on The Tree of Life, and it damn well ought to have been: there's audacity and then there's audacity. In a combination of practical effects and CGI used as minimally as possible, we see the coalescence of energy into matter and gaseous matter into solids, and into liquid, and the formation of the Earth in fire and stress, and the bubbles of Darwin's "little warm pond" where life began. We see cells and we see the primitive, shapeless jellyfish, animals thought to exist in much the same shape now as they did at the dawn of the fossil record; we see pleiosaurs and dinosaurs. I previously compared this sequence to the "Beyond the Infinite" chapter from Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey, in no small part because visual effects guru Douglas Trumbull was involved with both; I'll stand behind that, on the grounds that they are two of the most challenging, experimental sequences ever executed in an American narrative film, though I find I should qualify that comparison: they are, after all, representing polar opposites, the origin of existence versus the great leap into whatever comes after anything we know to call "existence".

Clipped aside from the film in which it occurs, this sequence is so beautiful that it's frankly not fair: certain visual concepts repeat themselves over and over again, most obviously a blue and orange nebula that is framed to look exactly like a blue and orange hot spring that is framed to look exactly like some blue and orange chemical process within the human genes. Several of the images are further repeated in the movie to come, though I did say we were clipping it out, didn't I? Shame on me.

It is a glorious, dramatic, frankly religious experience: it is Malick's attempt to find the mind of God and explore it, and he does so in such a way that The Tree of Life itself is both cathedral and sermon. And yet, this is not at all the simple act of glory it seems like. The pounding, immense piece of music that begins this sequence is the "Lacrimosa" from Zbigniew Preisner's Requiem for My Friend - noted spiritual filmmaker Krzysztof Kieślowski being the friend - and while it is clearly a liturgical piece, one needn't know that lacrimosa is the Latin for "defined by or causing a tearful state", or that the word is typically used to describe a particularly mournful movement in a requiem mass, to recognise that the sound of it is rather more dolorous than triumphal: here, the point seems to be that the act of creation is an inherently painful one, full of destruction (there are many images of fire in this sequence) and strife. We see the asteroid that wiped out most life at the K-T boundary. The much-anticipated dinosaurs are haunted by death: the pleiosaur is bleeding out of a hideous gash, one dinosaur looks around like a nervous cat, another is about to be devoured by a predator until something in its feeble beatings inspires some deep, primitive measure of pity.

And that is the flipside: there is mercy in the act of creation as well, for all creation is a gift. Violence is nature; generosity is grace.

Having taken us from the Big Bang to the version of Earth we know and love, The Tree of Life repeats this process on a far smaller scale. Mrs. O'Brien is pregnant, her stomach resembling the disc of Jupiter spotted earlier in the film, and for several minutes we watch as her three boys are born and grow to become preteens. By giving the same space in the movie to each of these disparate sequences (though the "youth in Waco" scenes are scored with infinitely lighter, more celebratory music), Malick invites us to understand how the birth and life of a child is situated within the birth and life of a universe: though we humans are an infinitesimally small component of the place we inhabit, we are still a component, and like it, we are miracles of creation.

In truth, it's this sequence that I like best in the whole movie: maybe because it is the most comforting, maybe because it is the sweetest. The shot of toddler Jack regarding infant R.L. with a supremely dubious look is, to me, one of the most exquisite moments in all of Malick's cinema.

It's only now, after some 40 minutes, that the "real film" actually starts: a delicate fable of life in a small town that boasts the most intimate, human-sized drama of anything Malick's done since his two '70s films, Badlands and Days of Heaven (I find it fascinating, and almost totally useless, that all of his works since his 20-year sabbatical ended in 1998 have started with the word "The", while neither of his first films did*). Jack is right at the cusp of adolescence, and starting to chafe under his father's lopsided, domineering, "white male in the '50s" attitude, while clinging to his mother and her ethereal femininity, the very embodiment of grace. Tiny moments abound, some of them troubling in their metaphoric overtones (Jack steals a neighbor's slip and then tosses it in a river, watching it float away), some heartbreaking (Jack's guilt over being party to a "game" of exploding a frog on a rocket; I like to think this was Malick's intentional nod to Lynne Ramsay's Ratcatcher, in recognition of her references to Badlands and Days of Heaven in that feature), some beautiful as nearly all the scenes of the three brothers goofing about. At least one brilliant moment is a combination of all of the above, as Jack enviously watches his father and R.L. - the one who dies, and who as a child looks so like Brad Pitt it's uncanny - noodling around with musical instruments (this sequence does all sorts of extra duty: it shows the middle child as inheriting the father's musical skill, but also the mother's sensitivity; while Jack, already aware, perhaps, that he is truly the son of his father despite his greater love for his mother, can do nothing but seethe).

The film is pleasurable in no small part because of its extremely specific observation: the moment-to-moment recreation of life in a certain place in a certain time (Malick, who grew up in Waco, would have been about Jack's age in the film's period), the details of family life, and the sharp depiction of its characters. Never before an actor of children, Malick nevertheless got a deep, wounded, yearning performance from McCracken, never asking him to embody an idea of American boyhood but always play this boy's impressions of this moment. Pitt's depiction of a barking man who wants to be better than he is is absolutely devastating: the way his face shows that he wishes, badly, to show his sons that he loves him, but cannot; the scene where he confronts the gap separating him from his fantasy of what he'd be able to accomplish, having been caught in a plant closing, is all the more heartbreaking since for so much of the movie we've been spotting the sensitive, bruised man hiding beneath the culturally-enforced shell, only to finally break in a far more tragic version of Col. Tall's "I've eaten untold buckets of shit" rant from The Thin Red Line.

Best in show, though, no doubt about it, is Chastain, the latest in Malick's storied career of promoting nobodies to prominent roles and seeing his gamble pay dividends: Sissy Spacek and Martin Sheen, Brooke Adams and Sam Shepard, Jim Caviezel and Ben Chaplin, Q'orianka Kilcher. It cannot have been fun to play a character who ends up, in the final cut, representing Womanhood, Spirituality, the Mother Goddess, and all that, and still make her come across as a breathing, thinking person; Chastain does this.

Even considering all this, The Tree of Life is so much more than a family drama, a familiar story told with uncommon beauty and skill. It is an attempt to grapple with the meaning of life and God and all: in its allusions to Job, it admits to asking the hoary old question, "if God is good, why is life so full of suffering?"; the relationship between the O'Briens is unmistakably a metaphor for the conflict between the traditional Abrahamic God as merciless patriarchal overlord and the more humanist, liberal Christianity tradition that sees God as the state of joy and bliss and total love. I don't think it's overreaching at all to suggest that adult Jack's skyscraper is framed so that it does not just reflect the sky "where God lives", as his mother once said; it indeed reaches up to heaven, trying to shorten the distance between man and God, not in the grasping, selfish way of the Tower of Babel, but out of desperate need to find solace in an world that offers none of it. Images that simply point the camera up and gawk at the heavens are almost as common in The Tree of Life as silken steadicam shots or dusky interiors - Emmanuel Lubezki, the first cinematographer to ever pull a second tour of duty with Malick, certainly nails all the warmth of his locations and shows how easily warmth can turn stifling and suffocating, once again as in The New World using little to no artificial light, and using the encroaching dusk to turn the simplest shots into visual poetry of the highest order - and the film palpably wants to pull God to it, to look God in the face, and ask without judgment, only whole-hearted curiosity, "Why?" The climactic sequence, in which adult Jack has a vision of happiness - call it Heaven, but the film does not - may be a bridge too far in terms of kitschey religious symbolism (I do not know my opinion on the matter, not yet), but it cannot be said to lack the courage of conviction. And I want to point out that Jack has this vision in the highest point of his skyscraper.

Here is how I know that The Tree of Life is a masterpiece: it does all of these things, and touches me so much that I can barely stand it, and there is basically not one single element in the film that speaks to me personally. I have no siblings, and cannot begin to speak to the veracity of the brotherly relationships that lend the film its most poignant and magical moments; I've didn't grow up in the kind of neighborhood where you could run around and stumble across wonderful things every which where; I have never had an acrimonious relationship with my father; I find the very idea of spotting Infinite Motherhood to be uncomfortably "othering" of women. And most crucially of all, I'm enough of a doctrinaire atheist that the questions, "Who is God? What is God thinking? How do we become closer to God?" are inherently as useful and compelling as wondering why we can't taste our own tongue. And despite all of these handicaps, the movie still feels like it's holding up a mirror: and it presents its intently specific story with such universal artistry and beauty and, yes, grace, that I cannot help but be swept up by it: twice I have seen the movie, and twice the moment that it ended felt like being violently shaken awake. I have now, twice, greeted the end of the movie with deep exhalation of feeling that reaches down into my toes, not sure if I should dance or cry from the unutterable glory of it.