Food, glorious food

It makes one feel at least slightly like an easy mark to be enormously enthusiastic for The Taste of Things, a movie that feels like it was created in a lab for people with middlebrow tastes who felt "sophisticated" when they watched European art cinema in the 1990s. It's French. It stars Juliette Binoche. Approximately 85% of the plot involves people cooking eating, or talking about cooking and eating. We could even probably stretch far enough to add "it was directed by Trần Anh Hùng" to the list: Hùng's name is another one of those things that gives me flashbacks to the '90s, the decade of his much-celebrated debut The Scent of Green Papaya, though I think you needed to be at least a second-order middlebrow art connoisseur to have moved into Southeast Asian art cinema back in those days.

The point being, The Taste of Things is not looking to push the medium forward, not one little bit, and its pleasures are very much the ones they would have been if this had actually come out early enough to be the Babette's Feast cash-in it resembles, rather than trailing that defining text of cinematic food porn by all of 36 years. It's blatantly nostalgic - it is about nostalgia, as well, the story of two old people looking at where they are in life and how they got there and, not without some melancholy, feeling like it was time well spent. It's a real nice, digestible film for people who want their movies to be lovely and warm and also not without some melancholy, but who want more or less the experience they knew was coming. None of which are the sorts of things I like to anoint as "strengths", but The Taste of Things has a certain X-factor in all of this: it is an extravagantly well-made version of all this. So well-made, in fact, that I would even say it has dethroned Babette's Feast from its long reign as the best live-action movie about food, in both the sense that it is a better movie qua movies, and it makes me much, much hungrier.

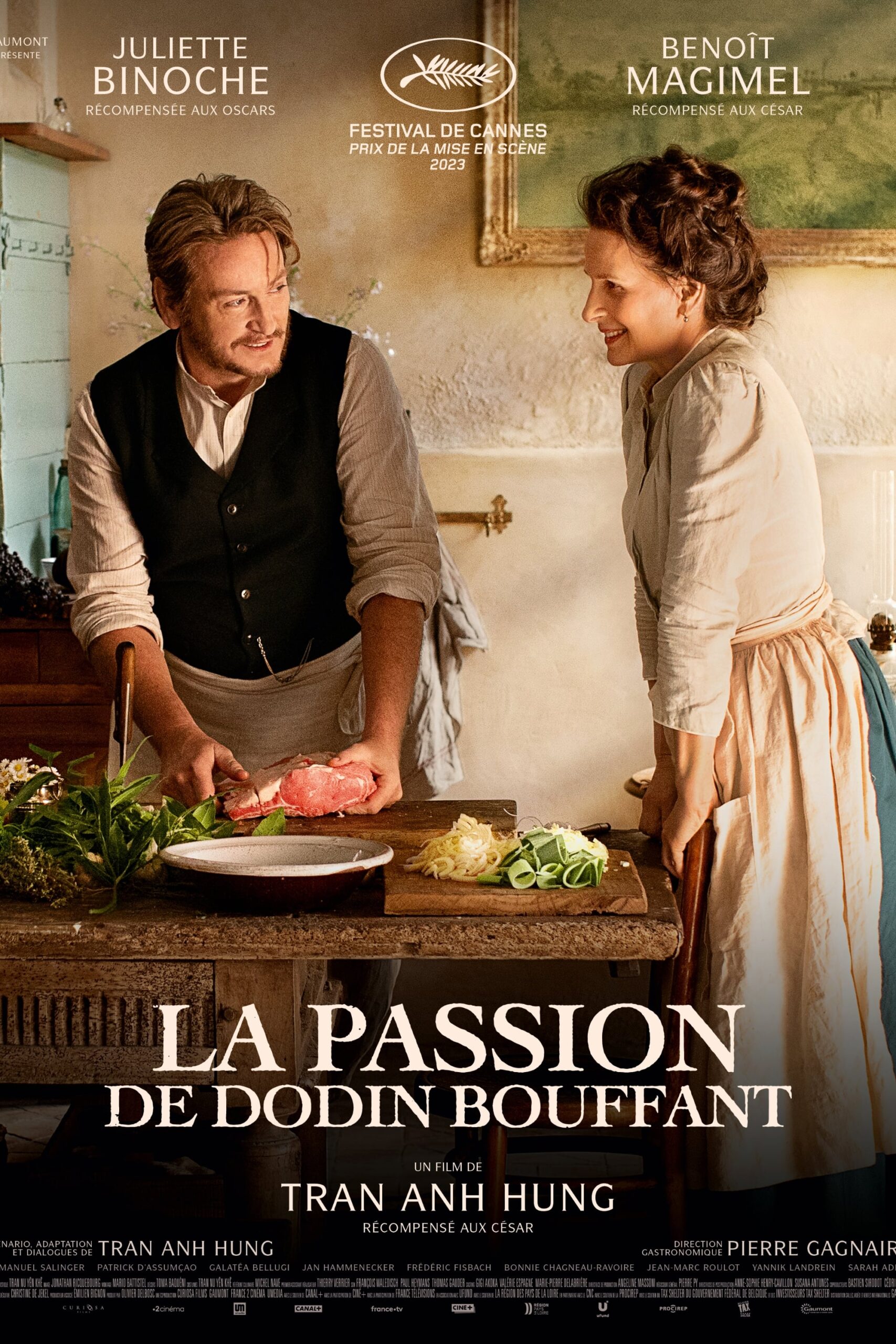

The story, which has been adapted (I gather rather freely) from a 1924 novel by Marcel Rouff, La vie et la passion de Dodin-Bouffant, Gourmet, is about the curious household of one Dodin Bouffant (Benoît Magimel), whose identity and history are somewhat vague. I's not clear where the money came from, in other words, but there was certainly a lot of it, and Dodin has a very nice country estate where he employs Eugénie (Binoche) to cook incredible meals for him; he often invites a coterie of his close friends who have the refinement to appreciate the gift of these meals to dine with him. It is genuinely not clear if there's anything else that he actually does. I gather this is how land-owning Frenchmen could structure their lives in the 1880s, and I am sorry to have missed my calling. At any rate, there might - might - be only one thing Dodin loves more than eating, which is Eugénie herself. This is in a small way a tragedy, because while she certainly loves him a lot, she definitely loves him less than she loves cooking for such an inexhaustibly appreciative audience, and all of his entreaties that the two of them should just get married already clearly concerns her that since everything is going so perfectly, it would be a shame to risk it all by changing anything. I would say, incidentally, that the original French title, The Passion of Dodin Bouffant, points in a much more direct way to the film's emotional center, which is, basically "the ways that love manifests"; it is a film where eating the food of somebody you cherish, much like preparing food for someone you cherish, can be intimate on a level equal to or greater than sex or romance. In this way it is much cruder but also more helpful than the English distribution title, which basically just says "food is in this movie".

But to the credit of the English distributors; boy, is there ever food in this movie. My 85% estimate is perhaps overstating things, since especially later in the movie, it's becoming clearer and clearer that food is a metaphor for domestic partnership, but it's still very attentive to cooking and eating as a process. The first 40 minutes or more of the movie are basically nothing else than demanding the viewer pump the brakes on whatever we're doing as someone in the 21st Century and just luxuriate in the slow pleasures of high cuisine. It literally opens with a series of instructions, as Eugénie explains what she's doing to Pauline (Bonnie Chagneau-Ravoire), the visiting niece of the kitchen assistant Violette (Galatea Bellugi), which both sets up elements in the story where Pauline will be made a representative of The Future Generation of French Gourmands, and also just provides an easy way for the film to let us know what we're seeing. But it's not just exposition: the cooking sequence, with its quick, sharp cutting to different elements of the food preparation process (the opening gambit of an ongoing editing schema that carefully distinguishes between "the scenes with lots of cuts" and "the scenes with long takes, many of them static", and has a very clear understanding of how a viewer is engaged in different states of emotional excitement by those things), is also an argument that this is a precisely calibrated art form, one that requires a great deal of wisdom and respect for the craft in addition to needing technical know-how. And this is cross-cut with a party of Dodin's friends enjoying the magnificent meal Eugénie has prepared and describing its perfection in language that feels like religious cant, up to the ritualistic and reverent way that they assemble to thank her for her skill and labor. Basically, the whole long opening act of The Taste of Things is a protracted argument that we would do well to actually think about what we're eating, and while I don't know that it precisely sets up the human drama that is to follow over the film's gracefully paced-out 134 minutes, it does create a very unmistakable mood, gently welcoming us into this world where appreciating well-made things and appreciating that someone has chosen to make these things for us are central aspects of moral human behavior. Or to put it another way, the film knows that if it's going to use food as a metaphor for all positive human emotion and connection, it needs to make the case, so it spends its opening hour or more making the case. This doesn't just include its indulgent and intoxicating cooking scenes; there's a terrific scene not long after where Dodin and his buddies gather for the post-mortem to discuss the complete disaster of a fancy dinner held by some dilettante prince who thinks that razzle-dazzle and excess are the key to great cuisine, rather than the almost spiritual understanding of how food works and what food does to the eater that Eugénie demonstrates. It goes on forever, all in one still take, and I found it to be one of the most playful and funny scenes in any 2023 film, which absolutely does not reflect well on me, but still.

This eventually turns into a more explicit story about the relationship, one of those muted French movie romances where it would be a melodramatic potboiler if everything wasn't being treated with such simplicity and pragmatism, and the weight shifts more squarely onto Binoche and Magimel, who are both outstanding (they were formerly a couple, and have a daughter together, and it's easy to assume that the warm camaraderie that exists in every scene between them is an extension of real-life fondness for each other). The "food porn" aspect dries up a little, though not entirely, and food as a metaphor persists right up until the end. Still, it's here that the film really begins to feel like an extremely well-made version of a fairly standard French art film. And while I can't help but make that sound like a criticism, let the record show that I led with the though "extremely well-made". Frankly, The Taste of Things can compete with any other 2023 film I've seen at the level of immaculate craftsmanship, never just handsome for the sake of it, though it is incredibly handsome. But the lush, prestige-picture beauty is keenly attuned to the story being told, the particular way that the food-forward narrative is trying to engage our emotions, and the way that a feeling of loss taints this beauty without necessarily making it ugly (it's a French movie, of course there's loss, and the first instant that a certain character coughs, I think we had all better understand exactly where things are headed, unless we have somehow not engaged with dramatic art prior to this). Jonathan Ricquebourg's cinematography is as much a co-star as Binoche and Magimel are; I have grown to greatly appreciate Ricqueborg's ability to make cinema look like aged paintings over the last few years (his work on The Death of Louis XIV remains some of my favorite cinematography from the 2010s), and he's basically doing more of the same here, attending to the way that natural light interacts with 19th Century interiors with ruthless perfectionism that never feels over-calculated even as it very deliberately creates a slight distance between us and the film, a feeling of chronological remoteness that augments every other part of the film: the acting, the cooking, the story about loss. And he also uses a pretty straightforward gimmick of color temperature (warm when it's happy, cold when it's sad) that feels so gracefully teased out of the sets that rather than coming across as visual bullying, it feels inevitable, like the film is caught up in the same fate as its cast. But even more than the lighting, what really makes the cinematography sing is the camera movement, gliding smoothly around spaces in a way that insists on the physical presence of the recording device, bringing the environment to life while also imposing the cinematic frame on it.

This all culminates in one of the year's great closing scenes, where the camera movement, the lighting, the blocking, and the dialogue all unite in a lovely little blurring of chronology that is tender and sweet in its own right, while also reflecting back on the entire movie up to that point, clarifying and deepening its emotional undercurrents. Which makes it even easier to be on the film's side, I think; nailing the ending is an art form all on its own. And it's nice to see a movie as generally impeccable as The Taste of Things rally to be at its most impeccable right at the end. This is, I believe, as close to a faultless movie as 2023 has produced.

The point being, The Taste of Things is not looking to push the medium forward, not one little bit, and its pleasures are very much the ones they would have been if this had actually come out early enough to be the Babette's Feast cash-in it resembles, rather than trailing that defining text of cinematic food porn by all of 36 years. It's blatantly nostalgic - it is about nostalgia, as well, the story of two old people looking at where they are in life and how they got there and, not without some melancholy, feeling like it was time well spent. It's a real nice, digestible film for people who want their movies to be lovely and warm and also not without some melancholy, but who want more or less the experience they knew was coming. None of which are the sorts of things I like to anoint as "strengths", but The Taste of Things has a certain X-factor in all of this: it is an extravagantly well-made version of all this. So well-made, in fact, that I would even say it has dethroned Babette's Feast from its long reign as the best live-action movie about food, in both the sense that it is a better movie qua movies, and it makes me much, much hungrier.

The story, which has been adapted (I gather rather freely) from a 1924 novel by Marcel Rouff, La vie et la passion de Dodin-Bouffant, Gourmet, is about the curious household of one Dodin Bouffant (Benoît Magimel), whose identity and history are somewhat vague. I's not clear where the money came from, in other words, but there was certainly a lot of it, and Dodin has a very nice country estate where he employs Eugénie (Binoche) to cook incredible meals for him; he often invites a coterie of his close friends who have the refinement to appreciate the gift of these meals to dine with him. It is genuinely not clear if there's anything else that he actually does. I gather this is how land-owning Frenchmen could structure their lives in the 1880s, and I am sorry to have missed my calling. At any rate, there might - might - be only one thing Dodin loves more than eating, which is Eugénie herself. This is in a small way a tragedy, because while she certainly loves him a lot, she definitely loves him less than she loves cooking for such an inexhaustibly appreciative audience, and all of his entreaties that the two of them should just get married already clearly concerns her that since everything is going so perfectly, it would be a shame to risk it all by changing anything. I would say, incidentally, that the original French title, The Passion of Dodin Bouffant, points in a much more direct way to the film's emotional center, which is, basically "the ways that love manifests"; it is a film where eating the food of somebody you cherish, much like preparing food for someone you cherish, can be intimate on a level equal to or greater than sex or romance. In this way it is much cruder but also more helpful than the English distribution title, which basically just says "food is in this movie".

But to the credit of the English distributors; boy, is there ever food in this movie. My 85% estimate is perhaps overstating things, since especially later in the movie, it's becoming clearer and clearer that food is a metaphor for domestic partnership, but it's still very attentive to cooking and eating as a process. The first 40 minutes or more of the movie are basically nothing else than demanding the viewer pump the brakes on whatever we're doing as someone in the 21st Century and just luxuriate in the slow pleasures of high cuisine. It literally opens with a series of instructions, as Eugénie explains what she's doing to Pauline (Bonnie Chagneau-Ravoire), the visiting niece of the kitchen assistant Violette (Galatea Bellugi), which both sets up elements in the story where Pauline will be made a representative of The Future Generation of French Gourmands, and also just provides an easy way for the film to let us know what we're seeing. But it's not just exposition: the cooking sequence, with its quick, sharp cutting to different elements of the food preparation process (the opening gambit of an ongoing editing schema that carefully distinguishes between "the scenes with lots of cuts" and "the scenes with long takes, many of them static", and has a very clear understanding of how a viewer is engaged in different states of emotional excitement by those things), is also an argument that this is a precisely calibrated art form, one that requires a great deal of wisdom and respect for the craft in addition to needing technical know-how. And this is cross-cut with a party of Dodin's friends enjoying the magnificent meal Eugénie has prepared and describing its perfection in language that feels like religious cant, up to the ritualistic and reverent way that they assemble to thank her for her skill and labor. Basically, the whole long opening act of The Taste of Things is a protracted argument that we would do well to actually think about what we're eating, and while I don't know that it precisely sets up the human drama that is to follow over the film's gracefully paced-out 134 minutes, it does create a very unmistakable mood, gently welcoming us into this world where appreciating well-made things and appreciating that someone has chosen to make these things for us are central aspects of moral human behavior. Or to put it another way, the film knows that if it's going to use food as a metaphor for all positive human emotion and connection, it needs to make the case, so it spends its opening hour or more making the case. This doesn't just include its indulgent and intoxicating cooking scenes; there's a terrific scene not long after where Dodin and his buddies gather for the post-mortem to discuss the complete disaster of a fancy dinner held by some dilettante prince who thinks that razzle-dazzle and excess are the key to great cuisine, rather than the almost spiritual understanding of how food works and what food does to the eater that Eugénie demonstrates. It goes on forever, all in one still take, and I found it to be one of the most playful and funny scenes in any 2023 film, which absolutely does not reflect well on me, but still.

This eventually turns into a more explicit story about the relationship, one of those muted French movie romances where it would be a melodramatic potboiler if everything wasn't being treated with such simplicity and pragmatism, and the weight shifts more squarely onto Binoche and Magimel, who are both outstanding (they were formerly a couple, and have a daughter together, and it's easy to assume that the warm camaraderie that exists in every scene between them is an extension of real-life fondness for each other). The "food porn" aspect dries up a little, though not entirely, and food as a metaphor persists right up until the end. Still, it's here that the film really begins to feel like an extremely well-made version of a fairly standard French art film. And while I can't help but make that sound like a criticism, let the record show that I led with the though "extremely well-made". Frankly, The Taste of Things can compete with any other 2023 film I've seen at the level of immaculate craftsmanship, never just handsome for the sake of it, though it is incredibly handsome. But the lush, prestige-picture beauty is keenly attuned to the story being told, the particular way that the food-forward narrative is trying to engage our emotions, and the way that a feeling of loss taints this beauty without necessarily making it ugly (it's a French movie, of course there's loss, and the first instant that a certain character coughs, I think we had all better understand exactly where things are headed, unless we have somehow not engaged with dramatic art prior to this). Jonathan Ricquebourg's cinematography is as much a co-star as Binoche and Magimel are; I have grown to greatly appreciate Ricqueborg's ability to make cinema look like aged paintings over the last few years (his work on The Death of Louis XIV remains some of my favorite cinematography from the 2010s), and he's basically doing more of the same here, attending to the way that natural light interacts with 19th Century interiors with ruthless perfectionism that never feels over-calculated even as it very deliberately creates a slight distance between us and the film, a feeling of chronological remoteness that augments every other part of the film: the acting, the cooking, the story about loss. And he also uses a pretty straightforward gimmick of color temperature (warm when it's happy, cold when it's sad) that feels so gracefully teased out of the sets that rather than coming across as visual bullying, it feels inevitable, like the film is caught up in the same fate as its cast. But even more than the lighting, what really makes the cinematography sing is the camera movement, gliding smoothly around spaces in a way that insists on the physical presence of the recording device, bringing the environment to life while also imposing the cinematic frame on it.

This all culminates in one of the year's great closing scenes, where the camera movement, the lighting, the blocking, and the dialogue all unite in a lovely little blurring of chronology that is tender and sweet in its own right, while also reflecting back on the entire movie up to that point, clarifying and deepening its emotional undercurrents. Which makes it even easier to be on the film's side, I think; nailing the ending is an art form all on its own. And it's nice to see a movie as generally impeccable as The Taste of Things rally to be at its most impeccable right at the end. This is, I believe, as close to a faultless movie as 2023 has produced.