Oh Ricky, you're so fine

A review requested by STinG, with thanks to supporting Alternate Ending as a donor through Patreon.

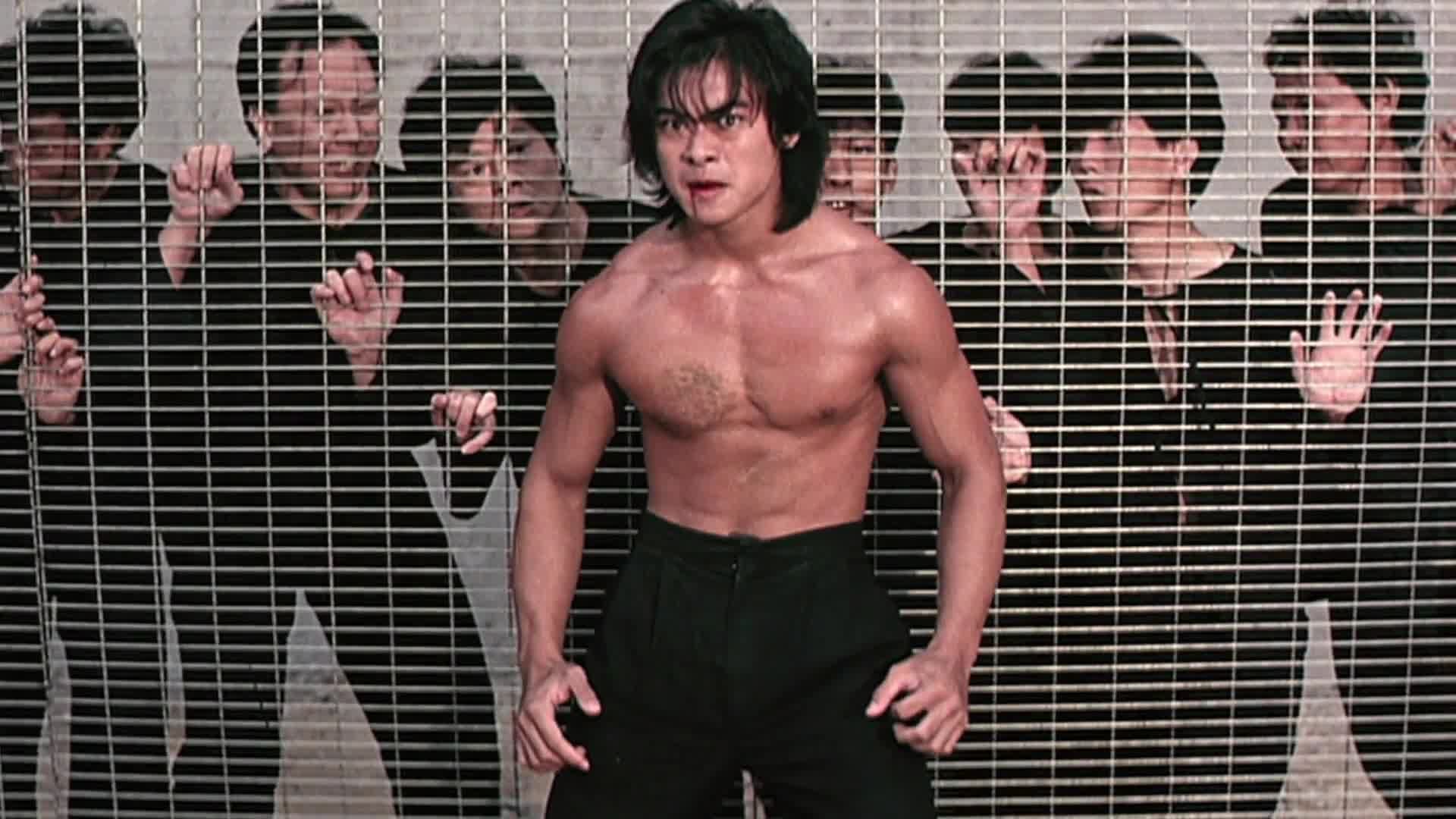

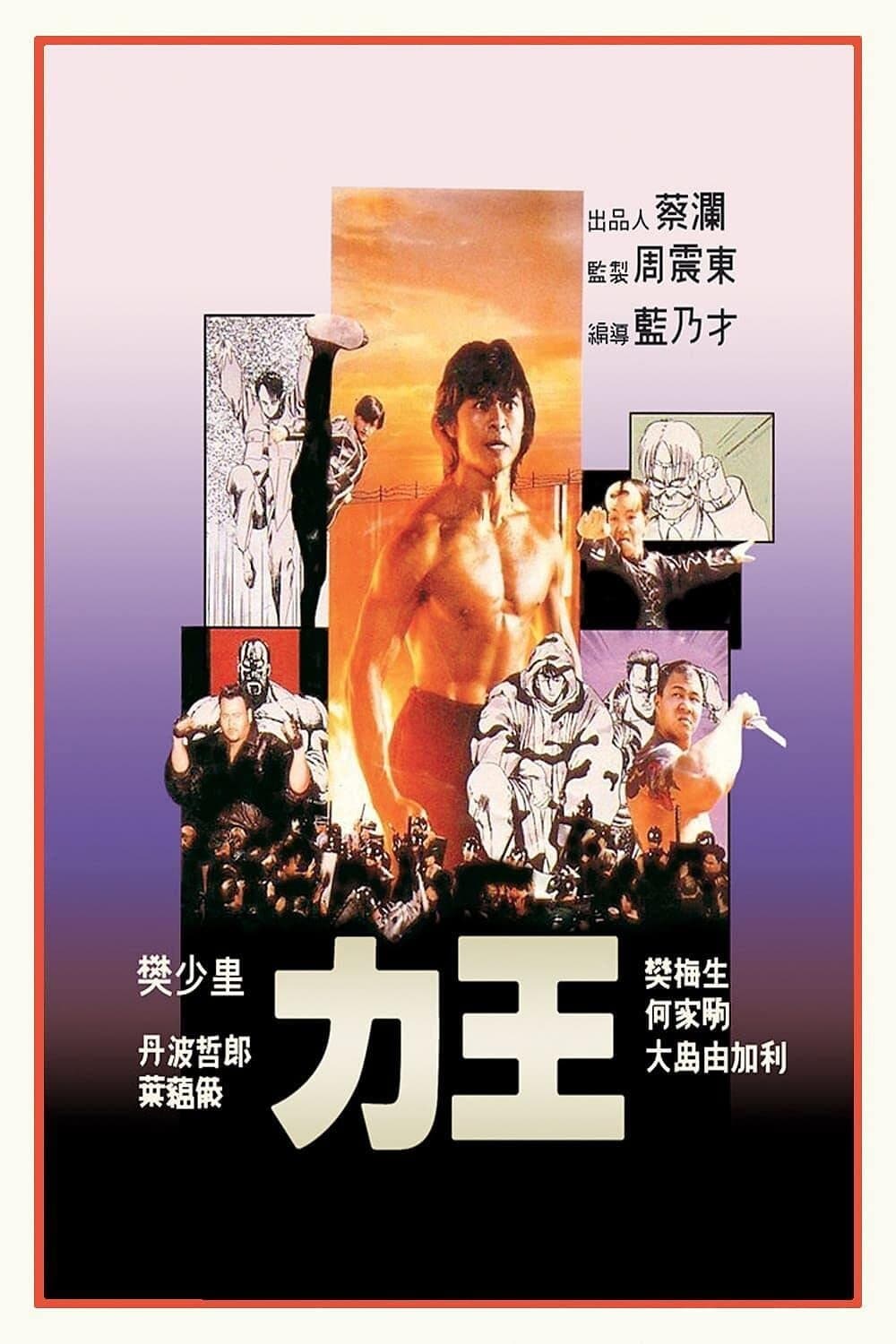

If there is such a thing as "objective" quality in cinema, then Riki-Oh: The Story of Ricky is objectively a bad movie. Fortunately, there is no such thing as objective quality in cinema. Sure, you could point to lots of problems with Riki-Oh (also released in the West as just The Story of Ricky, and in its native Hong Kong as Lik Wong, the protagonist's name): the sound recording is shit and the dubbing is clunky and obvious even watching the Cantonese version with English subtitles and absolutely no knowledge of Cantonese; the acting errs on the side of "enthusiastic hamminess" pretty much 100% of the time; the movie has forgotten its scenario within about 45 seconds of introducing it; director Lam Nai Choi is prone to selecting the most cheesy, trite compositions he can manage, and overindulging in tacky slow-motion effects. If ever a movie deserved to be called "cheesy", this does.

Let us flip that around, though: would correcting any of these apparent problems make Riki-Oh a "better" version of itself? And truthfully, I don't see how a person could possibly argue that they would. A great deal of the film's appeal - and for the right sort of viewer, this I think an extraordinarily appealing film - lies in its unselfconscious childish enthusiasm, an unrelenting delight in doing cool, stupid shit and doing it as hard as you possibly can. It feels like watching sweet-natured but somewhat dumb kids running around at top speed yelling at each other in a loose simulacrum of an action movie narrative, up to and including the part where they shake a machine gun that is very clearly not shooting bullets, while the sound of a gun firing is piped in on the soundtrack. It's basically the "grown adults with actual filmmaking resources" version of making "rat-a-tat" noises with your mouth while pointing a vaguely gun-shaped stick at somebody else.

Also, these are the sort of adult-sized children who think that there's nothing cooler than describing preposterously unlikely acts of gory violence in awestruck, holy detail. That's undeniably what Riki-Oh is best known for: its simply hallucinatory display of ludicrous gore. The plot - as distinct from the alleged "story", which is immaterial and trivial - is that Ricky (Fan Siu-Wong) is a functionally invincible martial arts genius who has pissed off the four gang leaders of the four wings of a prison, and so each one of them sends waves of fighters to kill him. This despite it being pretty clear after the first wave has been utterly demolished that Ricky literally cannot die or apparently take permanent damage; puncture wounds and such merely make him angrier. And in addition to that, he has such indescribably well-honed skills that he can, for all intents and purposes, make a dude fucking explode by punching him. He can, if nothing else, punch through human bodies with laughably little difficulty. So he leaves a wake of hideously mangled corpses and wish-they-were-corpses behind him, and a substantial part of the film's not-fucking-around 91-minute running time consists of watching he he produces those corpses. This takes very little time on a body-by-body basis, so the film compensates by putting in a very large number of bodies. All this is going on under the solitary remaining eye of assistant warden "Cyclops" Dan (Fan Mei-Sheng, Fan Siu-Wong's father), who coordinates the gangs' efforts to kill Ricky out of a fear that the prison is ripe for an uprising, and a charismatic killing machine like Ricky is just the man who is apt to trigger it. All of this nominally takes place in a futuristic private superprison in the year 2001, though there's virtually nothing in Riki-Oh that necessitates this kind of world-building, and I honestly don't know if anything happens anywhere in the movie proper that would actually clue you into the alleged setting, if we didn't get an opening title card explaining it.

Anyway, the gore. Ricky's indefatigable killing spree is accompanied by a cornucopia of the most unrelentingly gross violence that a transparently small quantity of money can buy. It pulls absolutely no punches, pardon the phrase: we see intestines being pulled out of bellies and then used to strangle people (the strangling being done by the people the intestines belong to, no less); we see holes being punched through chests, we see heads erupting in showers of blood, like jolly water balloons filled with bits of brain and skull. All of this is extremely disgusting, but even more importantly, all of this is extremely funny. Lam's directing has threaded an exceptionally fine needle, in which the tone has be balanced just so: the violent content is, as described, appalling and grotesque, while the physical production is absolutely the shoddiest, chintziest stuff imaginable, and the mood is bright, fluffy comedy. And we need that last thing to make the first two things feel delightful rather than just dumb. So on the one hand, I don't think any moderately sophisticated person could watch the violent setpieces and take them remotely seriously. Riki-Oh is not trying to put is in contact with the horrible fragility of the human body, using its viscera to unsettle and disgust us; it's not trying to shock us and make us outraged at its exploitative bad taste. It's trying to put on a show for us, optimistically and charmingly assuming that it can say "and this guy pulled out his own intestines, and he tried to strangle Ricky with them but Ricky still was able to pull out his intestines even more to kill him, it was so COOL", and we will respond with the same breathlessness and same fizzy, sugar-addled sense of what the word "cool" means. It very particularly does not want us to feel put out by the gore, to be made uncomfortable and disturbed; it wants us to laugh and cheer. The only thing I can think of that similarly goes overboard on extreme violence but then does everything in its power to undercut the intensity and authenticity of that violence, all in the spirit of a blithe comic sprint through genre tropes, is the following year's Dead Alive. And as is true in that film, the shabbiness of the production ends up being an active strength. It's not that the bloody make-up effects are "unrealistic" as such, and in fact in some cases they have a very vivid, wet plausibility to them. It's more that they've been filmed with flat, clean light and absolutely no sense of "atmosphere". By which I actually mean that the film has tons of atmosphere, but it's an atmosphere of hoke and kitsch, full of slow-motion and direct-address shots and a constant willingness to let us see the seams where this is all being faked. Those machine guns I mentioned, for example, or the way that the triumphant gesture that closes the film makes very little effort to disguise the cables and wires that made that triumphant gesture possible.

This low-rent cheesiness never lets up. It's present in the action scenes, and the way Lam frames them, as though he wanted every single composition to be a bigger kung fu movie cliché than the last. But it's also present in the "down" moments between the action scenes, which are really no less ridiculous and silly, and equally invested in a kind of campy seriousness that cares very much about making all of this exciting and fun without minding in the slightest if it's remotely convincing or plausible. This is maybe the most obvious in the performance by Wong Kwok-Leung, playing the son of the head warden (Ho Ka-Kui), a grown man dressed as an obese 8-year-old and leaning into all the goofy theatricality and hamminess of such a figure. He embodies the movie's entire ethos: being utterly silly and more than slightly dumb, and asking us to celebrate that fact rather than pretend that it's something more artful and weighty. It's the kind of movie that seems to have been so much fun to envision for the people who made it that I cannot help myself but be swept up in having just as much fun watching it: this is a movie that loves the excesses of tackily violent martial arts pictures, and it loves the fact that it got to copy them and then double-down on their excess. Given its exclusive focus on prison brutality and dismembered bodies, it's strange that my big take away is how single-mindedly Riki-Oh commits to the idea that movie making and movie watching should be joyous and fun, but that's exactly what this is: the singlemost joyous movie I've seen in months.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

If there is such a thing as "objective" quality in cinema, then Riki-Oh: The Story of Ricky is objectively a bad movie. Fortunately, there is no such thing as objective quality in cinema. Sure, you could point to lots of problems with Riki-Oh (also released in the West as just The Story of Ricky, and in its native Hong Kong as Lik Wong, the protagonist's name): the sound recording is shit and the dubbing is clunky and obvious even watching the Cantonese version with English subtitles and absolutely no knowledge of Cantonese; the acting errs on the side of "enthusiastic hamminess" pretty much 100% of the time; the movie has forgotten its scenario within about 45 seconds of introducing it; director Lam Nai Choi is prone to selecting the most cheesy, trite compositions he can manage, and overindulging in tacky slow-motion effects. If ever a movie deserved to be called "cheesy", this does.

Let us flip that around, though: would correcting any of these apparent problems make Riki-Oh a "better" version of itself? And truthfully, I don't see how a person could possibly argue that they would. A great deal of the film's appeal - and for the right sort of viewer, this I think an extraordinarily appealing film - lies in its unselfconscious childish enthusiasm, an unrelenting delight in doing cool, stupid shit and doing it as hard as you possibly can. It feels like watching sweet-natured but somewhat dumb kids running around at top speed yelling at each other in a loose simulacrum of an action movie narrative, up to and including the part where they shake a machine gun that is very clearly not shooting bullets, while the sound of a gun firing is piped in on the soundtrack. It's basically the "grown adults with actual filmmaking resources" version of making "rat-a-tat" noises with your mouth while pointing a vaguely gun-shaped stick at somebody else.

Also, these are the sort of adult-sized children who think that there's nothing cooler than describing preposterously unlikely acts of gory violence in awestruck, holy detail. That's undeniably what Riki-Oh is best known for: its simply hallucinatory display of ludicrous gore. The plot - as distinct from the alleged "story", which is immaterial and trivial - is that Ricky (Fan Siu-Wong) is a functionally invincible martial arts genius who has pissed off the four gang leaders of the four wings of a prison, and so each one of them sends waves of fighters to kill him. This despite it being pretty clear after the first wave has been utterly demolished that Ricky literally cannot die or apparently take permanent damage; puncture wounds and such merely make him angrier. And in addition to that, he has such indescribably well-honed skills that he can, for all intents and purposes, make a dude fucking explode by punching him. He can, if nothing else, punch through human bodies with laughably little difficulty. So he leaves a wake of hideously mangled corpses and wish-they-were-corpses behind him, and a substantial part of the film's not-fucking-around 91-minute running time consists of watching he he produces those corpses. This takes very little time on a body-by-body basis, so the film compensates by putting in a very large number of bodies. All this is going on under the solitary remaining eye of assistant warden "Cyclops" Dan (Fan Mei-Sheng, Fan Siu-Wong's father), who coordinates the gangs' efforts to kill Ricky out of a fear that the prison is ripe for an uprising, and a charismatic killing machine like Ricky is just the man who is apt to trigger it. All of this nominally takes place in a futuristic private superprison in the year 2001, though there's virtually nothing in Riki-Oh that necessitates this kind of world-building, and I honestly don't know if anything happens anywhere in the movie proper that would actually clue you into the alleged setting, if we didn't get an opening title card explaining it.

Anyway, the gore. Ricky's indefatigable killing spree is accompanied by a cornucopia of the most unrelentingly gross violence that a transparently small quantity of money can buy. It pulls absolutely no punches, pardon the phrase: we see intestines being pulled out of bellies and then used to strangle people (the strangling being done by the people the intestines belong to, no less); we see holes being punched through chests, we see heads erupting in showers of blood, like jolly water balloons filled with bits of brain and skull. All of this is extremely disgusting, but even more importantly, all of this is extremely funny. Lam's directing has threaded an exceptionally fine needle, in which the tone has be balanced just so: the violent content is, as described, appalling and grotesque, while the physical production is absolutely the shoddiest, chintziest stuff imaginable, and the mood is bright, fluffy comedy. And we need that last thing to make the first two things feel delightful rather than just dumb. So on the one hand, I don't think any moderately sophisticated person could watch the violent setpieces and take them remotely seriously. Riki-Oh is not trying to put is in contact with the horrible fragility of the human body, using its viscera to unsettle and disgust us; it's not trying to shock us and make us outraged at its exploitative bad taste. It's trying to put on a show for us, optimistically and charmingly assuming that it can say "and this guy pulled out his own intestines, and he tried to strangle Ricky with them but Ricky still was able to pull out his intestines even more to kill him, it was so COOL", and we will respond with the same breathlessness and same fizzy, sugar-addled sense of what the word "cool" means. It very particularly does not want us to feel put out by the gore, to be made uncomfortable and disturbed; it wants us to laugh and cheer. The only thing I can think of that similarly goes overboard on extreme violence but then does everything in its power to undercut the intensity and authenticity of that violence, all in the spirit of a blithe comic sprint through genre tropes, is the following year's Dead Alive. And as is true in that film, the shabbiness of the production ends up being an active strength. It's not that the bloody make-up effects are "unrealistic" as such, and in fact in some cases they have a very vivid, wet plausibility to them. It's more that they've been filmed with flat, clean light and absolutely no sense of "atmosphere". By which I actually mean that the film has tons of atmosphere, but it's an atmosphere of hoke and kitsch, full of slow-motion and direct-address shots and a constant willingness to let us see the seams where this is all being faked. Those machine guns I mentioned, for example, or the way that the triumphant gesture that closes the film makes very little effort to disguise the cables and wires that made that triumphant gesture possible.

This low-rent cheesiness never lets up. It's present in the action scenes, and the way Lam frames them, as though he wanted every single composition to be a bigger kung fu movie cliché than the last. But it's also present in the "down" moments between the action scenes, which are really no less ridiculous and silly, and equally invested in a kind of campy seriousness that cares very much about making all of this exciting and fun without minding in the slightest if it's remotely convincing or plausible. This is maybe the most obvious in the performance by Wong Kwok-Leung, playing the son of the head warden (Ho Ka-Kui), a grown man dressed as an obese 8-year-old and leaning into all the goofy theatricality and hamminess of such a figure. He embodies the movie's entire ethos: being utterly silly and more than slightly dumb, and asking us to celebrate that fact rather than pretend that it's something more artful and weighty. It's the kind of movie that seems to have been so much fun to envision for the people who made it that I cannot help myself but be swept up in having just as much fun watching it: this is a movie that loves the excesses of tackily violent martial arts pictures, and it loves the fact that it got to copy them and then double-down on their excess. Given its exclusive focus on prison brutality and dismembered bodies, it's strange that my big take away is how single-mindedly Riki-Oh commits to the idea that movie making and movie watching should be joyous and fun, but that's exactly what this is: the singlemost joyous movie I've seen in months.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.