A game of telephone

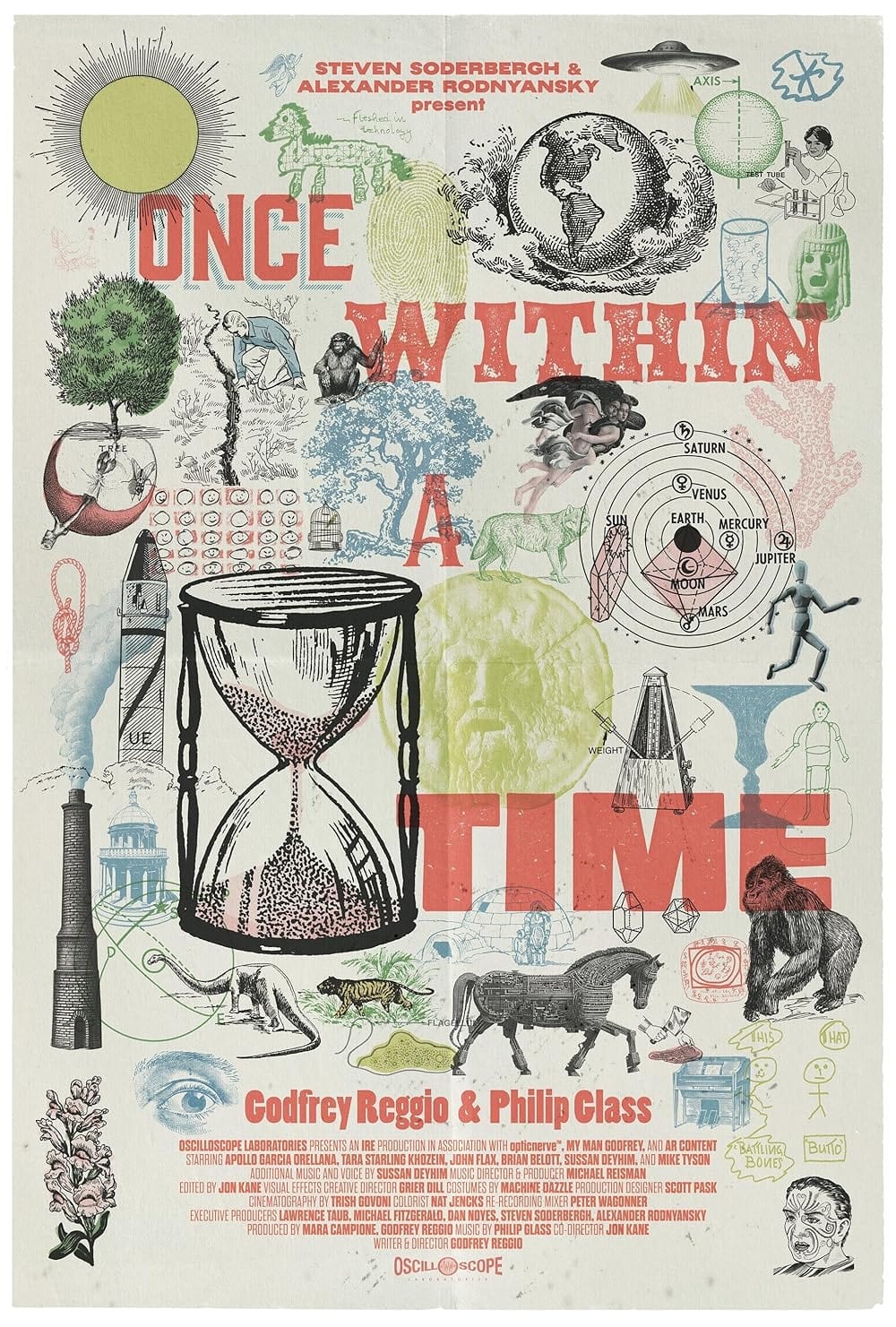

Once Within a Time is on the one hand, a film that I feel compelled to praise for being unsafe and experimental, especially since it had every reason not to be: director Godfrey Reggio is an octogenarian these days, after all, and in the year of our Lord 2023, when the primary mode of so much of cinema is blatantly retreading material and packaging it as nostalgia, there'd have been nobody kicking up a fuss, not really, if he just crapped out a retread of his four-decade-old feature debut, Koyaanisqatsi. But Reggio (assisted by Jon Kane as "co-director", which I assume is code for "the younger guy with the stamina to put Reggio's ideas into practice") has already made Koyaanisqatsi, and he's already sort of re-run it twice with its pair of quasi-sequels, and he wanted to try something new.

And so we get to my dangling "on the other hand", which is that Once Within a Time is also sort of a good example of why being safe and familiar isn't such a bad idea of all that: to be blunt about it, Reggio's ideas only work about two-thirds of the time, and the whole of the very short feature (a pleasant little 52 minutes, start to finish) is less than the sum of its best parts. And to be fair, a 66% success rate is still an admirable hit rate, but it's a further tragedy of Once Within a Time that the ideas that work generally dominate in the early going, and the ideas that face-plant generally seem to crop up more and more as the film races towards its conclusion. Indeed, maybe the single-most failed idea comes as late in the film as it possibly can, a little post-credits button that hangs a note of unreasonably sour irony on a film whose heavyhanded themes certainly didn't need the addition of such late-in-the-game irony, sour or otherwise. The result of all this is a decently enjoyable film at the level of "fancy, weird images plus Philip Glass movie", which has been the level on which nearly every one of Reggio's small number of films (five features including this one, plus two shorts) have been enjoyable, but still a distinctly flat note on which to presumably wrap up a career of limited productive but legendary impact: it's decidedly the second-worst project of Reggio's post-Koyaanisqatsi career, ahead of only the dismal 2002 catastrophe Naqoyqatsi, and it's kind of disappointing that he'd pop his head up one last time to muck up the aesthetic success of his last "I didn't actually expect you had another film in you" project, 2013's Visitors. But without risk, there can be no art, and I guess if Reggio wasn't the kind of person capable of producing a Once Withing a Time in his twilight years, he presumably wouldn't have been the kind of person capable of producing Koyaanisqatsi in middle age.

The question "what do we have in front of us?" is difficult to answer, but in short: this is Reggio's attempt at a fairy tale. It's by far the closest thing any of his films have come to having a narrative progression, even with several recurring characters, if you feel comfortable calling them that; they are anthropomorphic, anyways, and played by human actors. There is a woman who is also perhaps a tree, and who is filmed by Trish Govoni with a diffuse, silvery-yellow glow that serves as a pretty good cue for us to feel good about her presence; there are a man and a woman whose faces are at a certain point encased within lacey spheres, and who are scene with apples at a different point, fairly early on in the proceedings, and if at this point you haven't cracked the symbolism of Once Within a Time, don't worry, because it actually gets even more obvious. But that's basically it: a fall from Eden, which further images suggest is primarily the result of too much reliance on technology (first and foremost: smartphones) and adulation of pop culture, and in this case, at least, Reggio is repeating himself, because that has been the intended and/or explicit theme of at least three of his preceding films: Koyaanisqatsi, Naqoyqatsi, and his 1995 short film Evidence between them. But he's approaching it from a brand new aesthetic angle this time.

There is, to be fair, absolutely no possible doubt that Reggio has done this knowingly and deliberately. Indeed, in the 21 years since Naqoyqatsi, the director has made only two films, and both of them are direct responses to that unabashed failure: Visitors was a very clear anti-Naqoyqatsi, making basically every possible opposite choice from the ones that the older film made, and Once Within a Time is just as clearly an attempt to "fix" Naqoyqatsi. This is about as explicit as a film in which words are not spoken can make it: Once Within a Time goes so far as to recycle footage from the 2002 film. In fact, it recycles footage from all four of Reggio's previous features and the 1991 short Anima Mundi, giving this film a feeling of being simultaneously a summing-up of all the director's interests and themes from a career, a remix of his ideas in some brash new form, and to a certain extent a repudiation of them. But Naqoyqatsi footage certainly shows up most often, and in a somewhat self-mocking context: that film was intensely ugly in its litany of instantly-dated CGI when it was new, and the footage is mostly showing up here to serve as the garish sign of a technologically mediated life that's sprawling and messy and tasteless.

All of this is there if you want to go hunting for it, but to be fair to the movie, it's not really asking you to. One could just as easily view it strictly on the terms it presents to us as a self-contained 52-minute object; a weird little picture book-turned-nightmare about abandoning Paradise and then finding it difficult to make your way back there. The film has no real unifying aesthetic (one of the many ways in which it is a complete 180-degree swerve from Visitors, to which it also feels like a kind of counterargument, though not as overtly as it does to Naqoyqatsi), but more of an eclectic curio cabinet of visual conceits that "feel" right together. Perhaps it would be fair to say that if it has no obvious unity, at least it has a coherent, ongoing "vibe". Probably the most consistent thing one could point to is that the film has been coated in a layer of artificial grain and scratches, so it looks aged; there's more than a bit of Guy Maddin's silent film pastiches here, probably the most obvious stylistic touchstone we can compare it to, more even than Reggio's own work. This gives it a textured, tactile feeling, something closer to animation of paper cut-outs than actors and objects on a stage, and one of the most curious sensations generated by Once Within a Time is that it feels like several discrete layers decoupaged into a single image, when it's presumably the case that all of these elements were in fact physically together in the first place.

In keeping with the title and fairy tale theme, it feels a bit like the movie is playing with paper dolls, staging a sort of dream-Victoriana pantomime that's a little bit picture book, a little bit stagecraft, a little bit stop-motion animation. Some images feel like we're peering into tiny miniature rooms, some feel like we're watching people running in place in front of a greenscreen, some feel like an indoor playground themed as a technophobic parody of Oz, with the yellow brick road replaced by sleek black pavers made of dead smartphones. At times the images are very extraordinary - besides the tree woman, I was particularly taken with the cheerfully terrifying surrealism of a man wearing a giant pair of novelty teeth who hides inside the chest of a man who is also an apple - and at times they're just very silly; often you can read distinct symbolism into them but almost as often they're just strange. They are practically never boring, and with such a short window of time to race through them, the film hardly has a chance to feel like a slog anyways.

What they don't do, I've resignedly concluded, is add up to very much; there's real pleasure in the dreamy illogic of "here's a bunch of stuff I thought up, enjoy", but it really does feel like we're rifling through a collection of oddities with very little shape to it. And when it attempts to form a shape and actually resolve its "story", one begins to strongly wish that it had not done so. Still, it's not like we're drowning in wildly colorful, dementedly artificial collections of carnivalesque visionary imagery, and Reggio's dark bedtime story has the great merit of being unlike anything else. It's taking one big swing after another, connecting often enough for to be exciting to watch more than its frustrating; it's certainly not lazy, and some of its most brazenly wrongheaded choices are among its most elaborate and high-effort. I would not really want to recommend it to any living human being, but I'm happy that it exists, pumping its weird, joyfully cranky energy out into the world.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

And so we get to my dangling "on the other hand", which is that Once Within a Time is also sort of a good example of why being safe and familiar isn't such a bad idea of all that: to be blunt about it, Reggio's ideas only work about two-thirds of the time, and the whole of the very short feature (a pleasant little 52 minutes, start to finish) is less than the sum of its best parts. And to be fair, a 66% success rate is still an admirable hit rate, but it's a further tragedy of Once Within a Time that the ideas that work generally dominate in the early going, and the ideas that face-plant generally seem to crop up more and more as the film races towards its conclusion. Indeed, maybe the single-most failed idea comes as late in the film as it possibly can, a little post-credits button that hangs a note of unreasonably sour irony on a film whose heavyhanded themes certainly didn't need the addition of such late-in-the-game irony, sour or otherwise. The result of all this is a decently enjoyable film at the level of "fancy, weird images plus Philip Glass movie", which has been the level on which nearly every one of Reggio's small number of films (five features including this one, plus two shorts) have been enjoyable, but still a distinctly flat note on which to presumably wrap up a career of limited productive but legendary impact: it's decidedly the second-worst project of Reggio's post-Koyaanisqatsi career, ahead of only the dismal 2002 catastrophe Naqoyqatsi, and it's kind of disappointing that he'd pop his head up one last time to muck up the aesthetic success of his last "I didn't actually expect you had another film in you" project, 2013's Visitors. But without risk, there can be no art, and I guess if Reggio wasn't the kind of person capable of producing a Once Withing a Time in his twilight years, he presumably wouldn't have been the kind of person capable of producing Koyaanisqatsi in middle age.

The question "what do we have in front of us?" is difficult to answer, but in short: this is Reggio's attempt at a fairy tale. It's by far the closest thing any of his films have come to having a narrative progression, even with several recurring characters, if you feel comfortable calling them that; they are anthropomorphic, anyways, and played by human actors. There is a woman who is also perhaps a tree, and who is filmed by Trish Govoni with a diffuse, silvery-yellow glow that serves as a pretty good cue for us to feel good about her presence; there are a man and a woman whose faces are at a certain point encased within lacey spheres, and who are scene with apples at a different point, fairly early on in the proceedings, and if at this point you haven't cracked the symbolism of Once Within a Time, don't worry, because it actually gets even more obvious. But that's basically it: a fall from Eden, which further images suggest is primarily the result of too much reliance on technology (first and foremost: smartphones) and adulation of pop culture, and in this case, at least, Reggio is repeating himself, because that has been the intended and/or explicit theme of at least three of his preceding films: Koyaanisqatsi, Naqoyqatsi, and his 1995 short film Evidence between them. But he's approaching it from a brand new aesthetic angle this time.

There is, to be fair, absolutely no possible doubt that Reggio has done this knowingly and deliberately. Indeed, in the 21 years since Naqoyqatsi, the director has made only two films, and both of them are direct responses to that unabashed failure: Visitors was a very clear anti-Naqoyqatsi, making basically every possible opposite choice from the ones that the older film made, and Once Within a Time is just as clearly an attempt to "fix" Naqoyqatsi. This is about as explicit as a film in which words are not spoken can make it: Once Within a Time goes so far as to recycle footage from the 2002 film. In fact, it recycles footage from all four of Reggio's previous features and the 1991 short Anima Mundi, giving this film a feeling of being simultaneously a summing-up of all the director's interests and themes from a career, a remix of his ideas in some brash new form, and to a certain extent a repudiation of them. But Naqoyqatsi footage certainly shows up most often, and in a somewhat self-mocking context: that film was intensely ugly in its litany of instantly-dated CGI when it was new, and the footage is mostly showing up here to serve as the garish sign of a technologically mediated life that's sprawling and messy and tasteless.

All of this is there if you want to go hunting for it, but to be fair to the movie, it's not really asking you to. One could just as easily view it strictly on the terms it presents to us as a self-contained 52-minute object; a weird little picture book-turned-nightmare about abandoning Paradise and then finding it difficult to make your way back there. The film has no real unifying aesthetic (one of the many ways in which it is a complete 180-degree swerve from Visitors, to which it also feels like a kind of counterargument, though not as overtly as it does to Naqoyqatsi), but more of an eclectic curio cabinet of visual conceits that "feel" right together. Perhaps it would be fair to say that if it has no obvious unity, at least it has a coherent, ongoing "vibe". Probably the most consistent thing one could point to is that the film has been coated in a layer of artificial grain and scratches, so it looks aged; there's more than a bit of Guy Maddin's silent film pastiches here, probably the most obvious stylistic touchstone we can compare it to, more even than Reggio's own work. This gives it a textured, tactile feeling, something closer to animation of paper cut-outs than actors and objects on a stage, and one of the most curious sensations generated by Once Within a Time is that it feels like several discrete layers decoupaged into a single image, when it's presumably the case that all of these elements were in fact physically together in the first place.

In keeping with the title and fairy tale theme, it feels a bit like the movie is playing with paper dolls, staging a sort of dream-Victoriana pantomime that's a little bit picture book, a little bit stagecraft, a little bit stop-motion animation. Some images feel like we're peering into tiny miniature rooms, some feel like we're watching people running in place in front of a greenscreen, some feel like an indoor playground themed as a technophobic parody of Oz, with the yellow brick road replaced by sleek black pavers made of dead smartphones. At times the images are very extraordinary - besides the tree woman, I was particularly taken with the cheerfully terrifying surrealism of a man wearing a giant pair of novelty teeth who hides inside the chest of a man who is also an apple - and at times they're just very silly; often you can read distinct symbolism into them but almost as often they're just strange. They are practically never boring, and with such a short window of time to race through them, the film hardly has a chance to feel like a slog anyways.

What they don't do, I've resignedly concluded, is add up to very much; there's real pleasure in the dreamy illogic of "here's a bunch of stuff I thought up, enjoy", but it really does feel like we're rifling through a collection of oddities with very little shape to it. And when it attempts to form a shape and actually resolve its "story", one begins to strongly wish that it had not done so. Still, it's not like we're drowning in wildly colorful, dementedly artificial collections of carnivalesque visionary imagery, and Reggio's dark bedtime story has the great merit of being unlike anything else. It's taking one big swing after another, connecting often enough for to be exciting to watch more than its frustrating; it's certainly not lazy, and some of its most brazenly wrongheaded choices are among its most elaborate and high-effort. I would not really want to recommend it to any living human being, but I'm happy that it exists, pumping its weird, joyfully cranky energy out into the world.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

Categories: avant-garde, fantasy, message pictures, music