Comes a horse man

A review requested by WBTN, with thanks to supporting Alternate Ending as a donor through Patreon.

Do you have a movie you'd like to see reviewed? This and other perks can be found on our Patreon page!

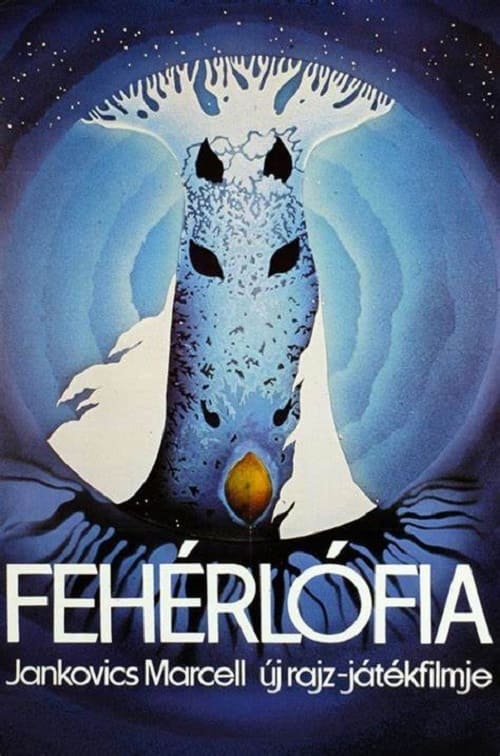

Any time a critic relies on the stock sentiment, "this is like nothing else," they're wrong. Everything is like something else. So I will hedge my words very carefully: whatever else is like Son of the White Mare, a 1981 animated feature made in Hungary by director Jankovics Marcell (who had earlier directed 1973's Johnny Corncob, generally claimed to be the first animated feature in Hungarian history), I haven't seen it and I don't know what it is. The film has precursors, in multiple media, but it still feels like thing itself is sui generis, a staggering invention of new aesthetic concepts that both augment the highly idiosyncratic way it tells its story, while not feeling like are naturally drawn from that story, but more enforced because Jankovics has some keen insight that these two random, disconnected stylistic modes would be more like peanut butter and chocolate than oil and water, or gasoline and a lit match. And then, having stormed out into the world in all of its boldness, receiving almost immediate acclaim (it was first fêted as one of the very greatest animated films of all time by the same 1984 gathering of critics and scholars that initially bestowed that honor on Yuri Norstein's Tale of Tales), it preceded to influence nothing of which am I personally aware - as though, having seen the extraordinary results that Jankovics and his animators achieved, every subsequent animator and animation director has soberly concluded "there's no way I can beat that", and has wisely refused to try.

Let us start at the simplest place: Son of the White Mare is based on a common folklore motif from the nomadic people of the western Eurasian Steppe (and is dedicated to the ancient people of the steppe), specifically in the form transmitted by the poet Arany László in 1862. The nucleus of the story is, in broad strokes, one of the more universal tales from folklore, win which a preternaturally, superhumanly strong man is joined by a small number of almost-equally-strong comrades in arms; they journey across the land vanquishing what needs to be vanquished and are in the end rewarded with the hands of some princesses and given small kingdoms to rule wisely and justly. In this case, the strong man is the human son of a white mare, just like it says, and his traveling companions are his two elder brother, which I believe is actually an example of Jankovics streamlining the story a bit: in the original, Fehérlófia, the son of the white mare, is not one of the three brothers, but he has been folded in with Fanyüvő ("Tree-Shaker"), who may or may not have been the youngest of the three in the old stories, I don't know and it doesn't really matter. He's the youngest one here, and that's the correct choice. At any rate, Fanyüvő/Fehérlófia, after the death of the mare who raises him to young adult (I want to say he's 14, but that might just be something I latched onto - the film's exposition is not slow or overly-fussed with details), decides to journey to kill the three dragons spreading evil around the world, and he does this after finding and proving himself to his long-lost older brothers Kőmorzsoló ("Stone-Crumbler") and Vasgyúró ("Iron-Rubber"). All three brothers are voiced by Cserhalmi György, which I feels is in and of itself a good indication of how much we are meant to care about distinctive characterisations and individual psychology in Son of the White Mare. The brothers find the dragons, through the unwilling aid of a cunning and annoying gnome, but defeating them just leads to other problems to solve, in the logic of fairy tale, where you tend to end up several miles away from where you were aiming, and by the time you get there you don't especially care anymore.

Animated films replicating this "stuff happens, whatever" narrative logic aren't the most common thing, but it's more common in animation than elsewhere, owing I imagine to how easy it is to depict inscrutable non-reality in the medium. So the mere fact that Son of the White Mare commits to the wandering nonsensical tone is not, in and of itself, what makes it such a wildly unusual film. Though it certainly does commit very hard to that tone, leaping across time and space with an indifferent shrug to such fussy matters where or how or how long such that it's somewhat hard to follow every little curve of the story; there's a degree to which one has to be willing to just roll with the film's swift flow, and just be fine with accepting where it is right now as The Absolute Most Important Thing Ever. So we're fighting a gnome now. Yes, but wasn't he a baby literally like seven minutes ago? Doesn't matter, we're fighting a gnome now.

It's pretty dizzying storytelling, but it is, at least, conventional: if you read European folklore, you pretty much get the drill, in terms of the torrential sweep of the narrative at least, if not the details. So it is that, perhaps uniquely in my experience of this mode of cinematic storytelling, the dream-logic thrust of the writing in Son of the White Mare turns out to be the grounded part, the familiar and predictable part. What Jankovics has done here isn't really at all marrying the storytelling of folklore to an appropriate style; I don't really know what Asiatic steppe folk art looks like, but I know enough to be confident that it isn't this. Instead, the filmmakers' goal has seemingly been to concoct an aesthetic that can match, visually, the warped otherworldly feeling of engaging with a story, the same feeling of "in my primitive ape brain, these elements seems familiar, but the whole thing feels like a fever dream as I try to pin it down" carried into animation. Sincerely, I don't know what the hell to even tell you about the look of Son of the White Mare, other than it is one of the most incredible works of animation I've ever seen, the kind of thing where you can tell within minutes of starting it that this is one of the absolute must-see animated features for anyone with even the slightest interest in the medium, and that's true even if we're limiting ourselves to, like, a top 5. I can tell you some of the things it reminded me of: at a first approximation, I might suggest that it feels like Russian Futurist poster art done with the day-glo colors and linework of '60s psychedelia. Which feels like an extremely pointed arrangement of influences for a Hungarian film released in 1981, when Hungarian Communism (perhaps the most humane and livable form of Communism then in the world, but it was still authoritarian) was in the very last stage of its "we can mostly make a pretty good and prosperous life for our citizens" era before collapsing over the course of the 1980s. But I also think that trying fit Son of the White Mare into some kind of schematic "it means this relative to its position in culture and politics" reading is a trap to be devoutly avoided: the experience of watching the movie feels much too acutely out-of-time (not the same as "timeless", not by a long shot), and its collision of Eastern and Western influences - which I am perhaps just making up in my own brain to have some kind of handle on this - feels more like it comes from Jankovic's hotly-burning subconscious more than from some place of calculation. To be honest, I don't know how you could calculate something like this.

Anyway, still trying to get at putting the aesthetic into words: the main thing I notice here is the color - bright, bold poster-paint colors, lashed into human shapes. It is, for the most part, representational art: people look like recognisable like people, castles look recognisably like castles, free-floating facial features with no corporeality look like nothing but the film has watched us how that evolved from the gnome, so it makes sense. But they're certainly not realistic people and castles: they're collections of smoothly flowing lines defining big chunks of color (this film does not have, that I can recall, a single example of using black outlines to define different parts of objects, a commonality to almost all cel animation practiced everywhere in the world), and while those blocks of color are typically more or less stable in the form and shape, they definitely aren't always. The depiction of Fanyüvő's birth and infancy, in particular, feels especially dreamlike in its collection of barely-coherent shapes in constant motion, as a more-or-less equine white form is overlaid with a block of color that twists and expands into a fetal shape; the baby Fanyüvő is mostly a human infant but then he kind of... just... is a baby horse in biped form, and you can sort of watch how the drawings transition to each other, but you also kind of feel this sense of "wait, was he always a horse, and I was just watching it wrong?" And then he's a person again, and you're suddenly not sure if he was ever a horse.

The opening several minutes of Son of the White Mare are, in this respect, its most challenging and confusing and quick-moving, and I like to imagine it's the film demanding that you prove yourself worthy of it: if you can keep up with the constant fluctuation of the prologue, then you may proceed to watch the rest of the movie. But it's never sedate. One of the things that I was not expecting at all, based on the incredibly mannered visual style and the fact that this is a 1981 animated feature from Hungary is that it would have such a high frame-rate; animation drawings cost money and time, and the more outré the design is, the harder it is to make sure that every drawing matches every other drawing, so a lot of times animation of this sort takes the easy path of reducing the frame-rate to a crawl (this happens in 1973's Belladonna of Sadness, a Japanese film that's one of the few things I can think of that's doing sort of what Son of the White Mare is doing prior to 1981. Though only sort of, and it's virtually impossible to imagine Jankovics having seen it, or possibly even knowing that it existed). Not so with this film! It is fluid as all hell, keeping its its bold and strange drawings in constant flux, fully breaking away from the folk art traditions that you can kind of see underpinning the stylisation and the character design by refusing to ever function as still images or poses, always reinventing themselves as new arrangements of shape and color that continue to evoke these characters but always with slight variations.

It's unbelievably dazzling and powerful, using these strong, almost abstract collections of colors and shapes that evoke primal, forceful emotions (the sunlike gold of Fanyüvő "reads" as "godlike hero" even without knowing a thing about him or what he's doing, for example) to create a movie that feels almost primitive in the way it works on the brain and eye. At the same time, calling anything this complex and sophisticated in its technique "primitive" would be discarding the meaning of that word altogether. This is an incredible achievement, one of the most visually spectacular animated features that has ever existed and I suspect ever will exist, and surely in the absolute topmost echelon of filmed folklore, in both cases tapping into something that is so incomprehensible foreign to the world of the late 20th Century that I genuinely cannot imagine how the filmmakers got themselves there.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

Do you have a movie you'd like to see reviewed? This and other perks can be found on our Patreon page!

Any time a critic relies on the stock sentiment, "this is like nothing else," they're wrong. Everything is like something else. So I will hedge my words very carefully: whatever else is like Son of the White Mare, a 1981 animated feature made in Hungary by director Jankovics Marcell (who had earlier directed 1973's Johnny Corncob, generally claimed to be the first animated feature in Hungarian history), I haven't seen it and I don't know what it is. The film has precursors, in multiple media, but it still feels like thing itself is sui generis, a staggering invention of new aesthetic concepts that both augment the highly idiosyncratic way it tells its story, while not feeling like are naturally drawn from that story, but more enforced because Jankovics has some keen insight that these two random, disconnected stylistic modes would be more like peanut butter and chocolate than oil and water, or gasoline and a lit match. And then, having stormed out into the world in all of its boldness, receiving almost immediate acclaim (it was first fêted as one of the very greatest animated films of all time by the same 1984 gathering of critics and scholars that initially bestowed that honor on Yuri Norstein's Tale of Tales), it preceded to influence nothing of which am I personally aware - as though, having seen the extraordinary results that Jankovics and his animators achieved, every subsequent animator and animation director has soberly concluded "there's no way I can beat that", and has wisely refused to try.

Let us start at the simplest place: Son of the White Mare is based on a common folklore motif from the nomadic people of the western Eurasian Steppe (and is dedicated to the ancient people of the steppe), specifically in the form transmitted by the poet Arany László in 1862. The nucleus of the story is, in broad strokes, one of the more universal tales from folklore, win which a preternaturally, superhumanly strong man is joined by a small number of almost-equally-strong comrades in arms; they journey across the land vanquishing what needs to be vanquished and are in the end rewarded with the hands of some princesses and given small kingdoms to rule wisely and justly. In this case, the strong man is the human son of a white mare, just like it says, and his traveling companions are his two elder brother, which I believe is actually an example of Jankovics streamlining the story a bit: in the original, Fehérlófia, the son of the white mare, is not one of the three brothers, but he has been folded in with Fanyüvő ("Tree-Shaker"), who may or may not have been the youngest of the three in the old stories, I don't know and it doesn't really matter. He's the youngest one here, and that's the correct choice. At any rate, Fanyüvő/Fehérlófia, after the death of the mare who raises him to young adult (I want to say he's 14, but that might just be something I latched onto - the film's exposition is not slow or overly-fussed with details), decides to journey to kill the three dragons spreading evil around the world, and he does this after finding and proving himself to his long-lost older brothers Kőmorzsoló ("Stone-Crumbler") and Vasgyúró ("Iron-Rubber"). All three brothers are voiced by Cserhalmi György, which I feels is in and of itself a good indication of how much we are meant to care about distinctive characterisations and individual psychology in Son of the White Mare. The brothers find the dragons, through the unwilling aid of a cunning and annoying gnome, but defeating them just leads to other problems to solve, in the logic of fairy tale, where you tend to end up several miles away from where you were aiming, and by the time you get there you don't especially care anymore.

Animated films replicating this "stuff happens, whatever" narrative logic aren't the most common thing, but it's more common in animation than elsewhere, owing I imagine to how easy it is to depict inscrutable non-reality in the medium. So the mere fact that Son of the White Mare commits to the wandering nonsensical tone is not, in and of itself, what makes it such a wildly unusual film. Though it certainly does commit very hard to that tone, leaping across time and space with an indifferent shrug to such fussy matters where or how or how long such that it's somewhat hard to follow every little curve of the story; there's a degree to which one has to be willing to just roll with the film's swift flow, and just be fine with accepting where it is right now as The Absolute Most Important Thing Ever. So we're fighting a gnome now. Yes, but wasn't he a baby literally like seven minutes ago? Doesn't matter, we're fighting a gnome now.

It's pretty dizzying storytelling, but it is, at least, conventional: if you read European folklore, you pretty much get the drill, in terms of the torrential sweep of the narrative at least, if not the details. So it is that, perhaps uniquely in my experience of this mode of cinematic storytelling, the dream-logic thrust of the writing in Son of the White Mare turns out to be the grounded part, the familiar and predictable part. What Jankovics has done here isn't really at all marrying the storytelling of folklore to an appropriate style; I don't really know what Asiatic steppe folk art looks like, but I know enough to be confident that it isn't this. Instead, the filmmakers' goal has seemingly been to concoct an aesthetic that can match, visually, the warped otherworldly feeling of engaging with a story, the same feeling of "in my primitive ape brain, these elements seems familiar, but the whole thing feels like a fever dream as I try to pin it down" carried into animation. Sincerely, I don't know what the hell to even tell you about the look of Son of the White Mare, other than it is one of the most incredible works of animation I've ever seen, the kind of thing where you can tell within minutes of starting it that this is one of the absolute must-see animated features for anyone with even the slightest interest in the medium, and that's true even if we're limiting ourselves to, like, a top 5. I can tell you some of the things it reminded me of: at a first approximation, I might suggest that it feels like Russian Futurist poster art done with the day-glo colors and linework of '60s psychedelia. Which feels like an extremely pointed arrangement of influences for a Hungarian film released in 1981, when Hungarian Communism (perhaps the most humane and livable form of Communism then in the world, but it was still authoritarian) was in the very last stage of its "we can mostly make a pretty good and prosperous life for our citizens" era before collapsing over the course of the 1980s. But I also think that trying fit Son of the White Mare into some kind of schematic "it means this relative to its position in culture and politics" reading is a trap to be devoutly avoided: the experience of watching the movie feels much too acutely out-of-time (not the same as "timeless", not by a long shot), and its collision of Eastern and Western influences - which I am perhaps just making up in my own brain to have some kind of handle on this - feels more like it comes from Jankovic's hotly-burning subconscious more than from some place of calculation. To be honest, I don't know how you could calculate something like this.

Anyway, still trying to get at putting the aesthetic into words: the main thing I notice here is the color - bright, bold poster-paint colors, lashed into human shapes. It is, for the most part, representational art: people look like recognisable like people, castles look recognisably like castles, free-floating facial features with no corporeality look like nothing but the film has watched us how that evolved from the gnome, so it makes sense. But they're certainly not realistic people and castles: they're collections of smoothly flowing lines defining big chunks of color (this film does not have, that I can recall, a single example of using black outlines to define different parts of objects, a commonality to almost all cel animation practiced everywhere in the world), and while those blocks of color are typically more or less stable in the form and shape, they definitely aren't always. The depiction of Fanyüvő's birth and infancy, in particular, feels especially dreamlike in its collection of barely-coherent shapes in constant motion, as a more-or-less equine white form is overlaid with a block of color that twists and expands into a fetal shape; the baby Fanyüvő is mostly a human infant but then he kind of... just... is a baby horse in biped form, and you can sort of watch how the drawings transition to each other, but you also kind of feel this sense of "wait, was he always a horse, and I was just watching it wrong?" And then he's a person again, and you're suddenly not sure if he was ever a horse.

The opening several minutes of Son of the White Mare are, in this respect, its most challenging and confusing and quick-moving, and I like to imagine it's the film demanding that you prove yourself worthy of it: if you can keep up with the constant fluctuation of the prologue, then you may proceed to watch the rest of the movie. But it's never sedate. One of the things that I was not expecting at all, based on the incredibly mannered visual style and the fact that this is a 1981 animated feature from Hungary is that it would have such a high frame-rate; animation drawings cost money and time, and the more outré the design is, the harder it is to make sure that every drawing matches every other drawing, so a lot of times animation of this sort takes the easy path of reducing the frame-rate to a crawl (this happens in 1973's Belladonna of Sadness, a Japanese film that's one of the few things I can think of that's doing sort of what Son of the White Mare is doing prior to 1981. Though only sort of, and it's virtually impossible to imagine Jankovics having seen it, or possibly even knowing that it existed). Not so with this film! It is fluid as all hell, keeping its its bold and strange drawings in constant flux, fully breaking away from the folk art traditions that you can kind of see underpinning the stylisation and the character design by refusing to ever function as still images or poses, always reinventing themselves as new arrangements of shape and color that continue to evoke these characters but always with slight variations.

It's unbelievably dazzling and powerful, using these strong, almost abstract collections of colors and shapes that evoke primal, forceful emotions (the sunlike gold of Fanyüvő "reads" as "godlike hero" even without knowing a thing about him or what he's doing, for example) to create a movie that feels almost primitive in the way it works on the brain and eye. At the same time, calling anything this complex and sophisticated in its technique "primitive" would be discarding the meaning of that word altogether. This is an incredible achievement, one of the most visually spectacular animated features that has ever existed and I suspect ever will exist, and surely in the absolute topmost echelon of filmed folklore, in both cases tapping into something that is so incomprehensible foreign to the world of the late 20th Century that I genuinely cannot imagine how the filmmakers got themselves there.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.