The Devil in Miss Jeanne

To translate Belladonna of Sadness into an American context, imagine that Walt Disney, after building his empire, got bored, quit the company that bore his name, and went off to make Fritz the Cat. That's basically what happened with Tezuka Osamu, who is often (reductively) called the father of manga, largely on the basis of his adorable, big-eyed robot kid Astro Boy, star of the comic page and the television screen. That character's 1952 debut didn't actually invent anything, but it immediately popularised a very particular cartoon aesthetic (one that shows no signs of losing its popularity almost three-quarters of a century later), and made Tezuka an instant beloved celebrity. He founded his own animation studio in the early 1960s, Mushi Production, and turned Astro Boy into the nation's first animated series to find commercial success outside of Japan; from this moment on, he was a full-on icon, the adorable beret-wearing mascot of all anime.

And he quickly grew bored of this. By the end of the '60, Tezuka decided to start pushing the medium he'd helped to solidify, making the bold decision to create - get this - an animated film for adults. Like, erotically for adults. The result was 1969's A Thousand and One Nights, the first of a planned series of adults-only animated art; it was followed in 1970 by Cleopatra, a time-traveling sci-fi story about the famous Egyptian queen. At this point, Tezuka grew restless again, and left Mushi Production to pursue other interests. He did, however, retain a producer credit on a third film in the adult series, helping to develop the concepts early on in its development. And here we are at that third film, Belladonna of Sadness, as directed by Yamamoto Eiichi, who'd co-directed the first two films and had been something of a protégé of Tezuka's for years.

The third film, and the final one. Tezuka wasn't much of a businessman, and in order to keep work flowing in, was willing to operate for such low rates that Mushi Production basically couldn't survive any major flops. And Belladonna of Sadness turned out to be just such a flop. By the end of 1973, Mushi Production had declared bankruptcy, and that pretty much sank the movie into a profound obscurity. It wasn't completely forgotten in Japan, but its first release in North America had to wait until 2009, and it wasn't until a 2015 restoration that patched up some gaps left by the censors for a 1979 re-release in its home country that it finally began to accrue any kind of attention whatsoever in the English-speaking world. And here we are, ready to lavish some of that attention on it.

Good Lord, what an experience it is. Sexually explicit and violent animation might have been too much for audiences in the early 1970s, but it's not much of a shock these days - sexually explicit and violent animation from Japan, especially. The thing is, Belladonna of Sadness doesn't resemble anything that we might think of when we think of animation from Japan. Hell, I'm not sure what it resembles. It's deeply unfamiliar, is the point, but it's unfamiliar in a way that does feel very much of its era (or rather, of slightly before its era - I don't know the timeline of '60s-style psychedelia in Japan, but at least in the States, I'm pretty sure this would have looked humiliatingly dated in 1973). And somehow, decades later, the film still feels transgressive because of that. Or perhaps it's just that the style is so absolutely wild that it puts one in a receptive mood to the shocking, nightmarish quality to the images.

But before I go any deeper into that, it's definitely time for a quick plot summary, or else I will never find a way to get back to it. The film's script, by Yamamoto and Fukuda Yoshiyuki, is inspired by Jules Michelet's 1862 La Sorcière, one of the earliest sympathetic (albeit inaccurate) histories of witchcraft in the middle ages. I have not the slightest idea if the particular story Belladonna of Sadness tells was recounted by Michelet or if Yamamoto and Fukuda just took some ideas, but it is set in feudal France, at least, and centers on a young couple in love named Jean (Ito Katsutaka) and Jeanne (Nagayama Aiko). Our story begins with them appealing to the local lord (Takahashi Masaya) for permission to marry; rather than granting it, the lord throws Jean out and brutally rapes Jeanne. After this horrifying ordeal, she is visited by a curious visitor (Nakadai Tatsuya), a tiny man in a white coat with a big pink head - rather much like a jolly leprechaun-esque penis, in fact. And he promises Jeanne all the power she needs to utterly destroy the lord. For the little penis man is, of course, the Devil, and by the time Jeanne's revenge is complete, she will have become the most powerful witch in the land.

That's a pretty basic fable, of course, but it's hard to imagine how Belladonna of Sadness could possibly tell a more complicated story than that one. Frankly, it's already hard enough to follow the straightforward archetypes on display. And this brings us back to the film's style, which is incredibly fucking intense. It is, for much of its running time, the simplest possible kind of "animated" film, God forgive me for using that word: one drawing, laid underneath the camera, and sometimes the camera pans across it, or rotates over it. We hear voices, and to a certain extent, the powerful relationship between sound and image is enough to force relationships between those voices and the drawings, so that we detect a kind of rudimentary life in the images even without any illusion of movement.

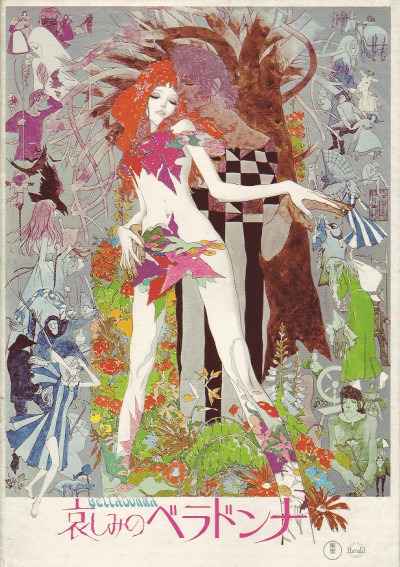

The hell of it is, even if that's literally all there was to the film, that might still be enough. Because the artwork in Belladonna of Sadness is absolutely jaw-dropping. It's very "of the late '60s"; the lines generally and the approach to caricaturing the human face owe a distinct debt to Pop Art and an even more distinct debt to psychedelia; the whole film feels more than a little like a chain of prog and art-rock album covers (which fits in nicely with Sato Masahiko's score, which sounds more than a little like some odd, folkified variant of prog). But there's some je ne sais quois in the way this style is applied by the animators, maybe because there's a little bit of wood-cut illustrations from a European book of fairy tales, too. One thing that there's definitely not is the rounded, appealing style that Tezuka gave to the world; it's as thorough a rejection of customary Japanese animation aesthetics as any Japanese animated film that I can name.

So we have this wonderful, fable-like psychedelic chain of imagery, and then here's the thing: it is an animated film, despite those scare quotes I used earlier. And goodness me, does Yamamoto make sure to make that fact count. Movement in the film is very directly linked to the intrusion of the paranormal into the world; it can't possibly get clearer than when the small penis-devil appears to Jeanne, and she's a static drawing while he cavorts all around. But movement is also connected with suffering and evil, and the film makes... I am not prepared to say, good use of this, but certainly very effective use of this, during its altogether apocalyptic rape scene. We've gotten through several minutes of the film, sinking into the cool rhythms of all these static drawings, with the camera panning over them, and then suddenly we see a much less detailed drawing of Jeanne being split in two by a bright red gash that starts at her genitals and moves up her entire body, which eventually dissolves into a flock of bright red bats swirling around madly. It's the stuff of nightmares, and expertly placed into the film just right to completely throw us off balance; if the first few minutes are all about us shouting, dismayed, "but this isn't how animated movies work!", now the shouting becomes, "but this isn't how Belladonna of Sadness works!", and it is as thoroughly sickening as it needs to be to motivate the rest of the film.

Also, it turns out, that is how Belladonna of Sadness works, insofar as "do something that will be shocking and upsetting because it can't be predicted" is a strategy. The film's embrace of psychedelia tends towards the weird and grotesque, and when it needs to, it abandons this aesthetic for oozing black shapes, and unpleasantly surreal depictions of bodies as made out of something that really does not seem to be flesh. It is, you will please forgive me for saying, like a bad trip. The film rarely repeats any technique - this scene will be painted in such thin watercolors that the texture of the paper is more apparent than the shape of the drawing; this scene will cut between static images so quickly that they only barely register, but they still refuse to animate; this scene incorporates live-action footage, though God knows what its footage of. It does, near the very end, start to go around in circles, and thus the film has the great misfortune to start dragging in its last quarter or so; it doesn't end up rallying, either. But the whole thing is so obviously a visual aesthetic experience that barely even uses narrative as a pretext that I barely know if it matters.

It's hard to feel anything but stunned while the movie is ongoing: it hits hard, and it keeps hitting, and even the moments that are narratively light are still heavy with the foggy dream-like quality of the artwork. And for all this, I have nothing but admiration for the film. I'll admit, though, that the whole thing feels very much like what I don't like about "animation for adults": the violence, the sex, the sexual violence, are all just a lot. We're not, for God's sake, in Ralph Bakshi territory; the sheer indulgent excess of the style and the gorgeously detailed artwork means that the film unquestionably has more on its mind than simply provoking like a snotty, nihilistic teenager. Still, it is a provocation, and I invariably find provocations at least slightly tiresome. Maybe if they all looked as stunning as this, that wouldn't be the case. Still, the film has a definite case of grimdark edginess - a mild one, but it's enough to make me ever so slightly suspicious of the enormous impact that the film had on me as I was watching it.

And he quickly grew bored of this. By the end of the '60, Tezuka decided to start pushing the medium he'd helped to solidify, making the bold decision to create - get this - an animated film for adults. Like, erotically for adults. The result was 1969's A Thousand and One Nights, the first of a planned series of adults-only animated art; it was followed in 1970 by Cleopatra, a time-traveling sci-fi story about the famous Egyptian queen. At this point, Tezuka grew restless again, and left Mushi Production to pursue other interests. He did, however, retain a producer credit on a third film in the adult series, helping to develop the concepts early on in its development. And here we are at that third film, Belladonna of Sadness, as directed by Yamamoto Eiichi, who'd co-directed the first two films and had been something of a protégé of Tezuka's for years.

The third film, and the final one. Tezuka wasn't much of a businessman, and in order to keep work flowing in, was willing to operate for such low rates that Mushi Production basically couldn't survive any major flops. And Belladonna of Sadness turned out to be just such a flop. By the end of 1973, Mushi Production had declared bankruptcy, and that pretty much sank the movie into a profound obscurity. It wasn't completely forgotten in Japan, but its first release in North America had to wait until 2009, and it wasn't until a 2015 restoration that patched up some gaps left by the censors for a 1979 re-release in its home country that it finally began to accrue any kind of attention whatsoever in the English-speaking world. And here we are, ready to lavish some of that attention on it.

Good Lord, what an experience it is. Sexually explicit and violent animation might have been too much for audiences in the early 1970s, but it's not much of a shock these days - sexually explicit and violent animation from Japan, especially. The thing is, Belladonna of Sadness doesn't resemble anything that we might think of when we think of animation from Japan. Hell, I'm not sure what it resembles. It's deeply unfamiliar, is the point, but it's unfamiliar in a way that does feel very much of its era (or rather, of slightly before its era - I don't know the timeline of '60s-style psychedelia in Japan, but at least in the States, I'm pretty sure this would have looked humiliatingly dated in 1973). And somehow, decades later, the film still feels transgressive because of that. Or perhaps it's just that the style is so absolutely wild that it puts one in a receptive mood to the shocking, nightmarish quality to the images.

But before I go any deeper into that, it's definitely time for a quick plot summary, or else I will never find a way to get back to it. The film's script, by Yamamoto and Fukuda Yoshiyuki, is inspired by Jules Michelet's 1862 La Sorcière, one of the earliest sympathetic (albeit inaccurate) histories of witchcraft in the middle ages. I have not the slightest idea if the particular story Belladonna of Sadness tells was recounted by Michelet or if Yamamoto and Fukuda just took some ideas, but it is set in feudal France, at least, and centers on a young couple in love named Jean (Ito Katsutaka) and Jeanne (Nagayama Aiko). Our story begins with them appealing to the local lord (Takahashi Masaya) for permission to marry; rather than granting it, the lord throws Jean out and brutally rapes Jeanne. After this horrifying ordeal, she is visited by a curious visitor (Nakadai Tatsuya), a tiny man in a white coat with a big pink head - rather much like a jolly leprechaun-esque penis, in fact. And he promises Jeanne all the power she needs to utterly destroy the lord. For the little penis man is, of course, the Devil, and by the time Jeanne's revenge is complete, she will have become the most powerful witch in the land.

That's a pretty basic fable, of course, but it's hard to imagine how Belladonna of Sadness could possibly tell a more complicated story than that one. Frankly, it's already hard enough to follow the straightforward archetypes on display. And this brings us back to the film's style, which is incredibly fucking intense. It is, for much of its running time, the simplest possible kind of "animated" film, God forgive me for using that word: one drawing, laid underneath the camera, and sometimes the camera pans across it, or rotates over it. We hear voices, and to a certain extent, the powerful relationship between sound and image is enough to force relationships between those voices and the drawings, so that we detect a kind of rudimentary life in the images even without any illusion of movement.

The hell of it is, even if that's literally all there was to the film, that might still be enough. Because the artwork in Belladonna of Sadness is absolutely jaw-dropping. It's very "of the late '60s"; the lines generally and the approach to caricaturing the human face owe a distinct debt to Pop Art and an even more distinct debt to psychedelia; the whole film feels more than a little like a chain of prog and art-rock album covers (which fits in nicely with Sato Masahiko's score, which sounds more than a little like some odd, folkified variant of prog). But there's some je ne sais quois in the way this style is applied by the animators, maybe because there's a little bit of wood-cut illustrations from a European book of fairy tales, too. One thing that there's definitely not is the rounded, appealing style that Tezuka gave to the world; it's as thorough a rejection of customary Japanese animation aesthetics as any Japanese animated film that I can name.

So we have this wonderful, fable-like psychedelic chain of imagery, and then here's the thing: it is an animated film, despite those scare quotes I used earlier. And goodness me, does Yamamoto make sure to make that fact count. Movement in the film is very directly linked to the intrusion of the paranormal into the world; it can't possibly get clearer than when the small penis-devil appears to Jeanne, and she's a static drawing while he cavorts all around. But movement is also connected with suffering and evil, and the film makes... I am not prepared to say, good use of this, but certainly very effective use of this, during its altogether apocalyptic rape scene. We've gotten through several minutes of the film, sinking into the cool rhythms of all these static drawings, with the camera panning over them, and then suddenly we see a much less detailed drawing of Jeanne being split in two by a bright red gash that starts at her genitals and moves up her entire body, which eventually dissolves into a flock of bright red bats swirling around madly. It's the stuff of nightmares, and expertly placed into the film just right to completely throw us off balance; if the first few minutes are all about us shouting, dismayed, "but this isn't how animated movies work!", now the shouting becomes, "but this isn't how Belladonna of Sadness works!", and it is as thoroughly sickening as it needs to be to motivate the rest of the film.

Also, it turns out, that is how Belladonna of Sadness works, insofar as "do something that will be shocking and upsetting because it can't be predicted" is a strategy. The film's embrace of psychedelia tends towards the weird and grotesque, and when it needs to, it abandons this aesthetic for oozing black shapes, and unpleasantly surreal depictions of bodies as made out of something that really does not seem to be flesh. It is, you will please forgive me for saying, like a bad trip. The film rarely repeats any technique - this scene will be painted in such thin watercolors that the texture of the paper is more apparent than the shape of the drawing; this scene will cut between static images so quickly that they only barely register, but they still refuse to animate; this scene incorporates live-action footage, though God knows what its footage of. It does, near the very end, start to go around in circles, and thus the film has the great misfortune to start dragging in its last quarter or so; it doesn't end up rallying, either. But the whole thing is so obviously a visual aesthetic experience that barely even uses narrative as a pretext that I barely know if it matters.

It's hard to feel anything but stunned while the movie is ongoing: it hits hard, and it keeps hitting, and even the moments that are narratively light are still heavy with the foggy dream-like quality of the artwork. And for all this, I have nothing but admiration for the film. I'll admit, though, that the whole thing feels very much like what I don't like about "animation for adults": the violence, the sex, the sexual violence, are all just a lot. We're not, for God's sake, in Ralph Bakshi territory; the sheer indulgent excess of the style and the gorgeously detailed artwork means that the film unquestionably has more on its mind than simply provoking like a snotty, nihilistic teenager. Still, it is a provocation, and I invariably find provocations at least slightly tiresome. Maybe if they all looked as stunning as this, that wouldn't be the case. Still, the film has a definite case of grimdark edginess - a mild one, but it's enough to make me ever so slightly suspicious of the enormous impact that the film had on me as I was watching it.

Categories: animation, fantasy, japanese cinema, violence and gore