Get everybody and the stuff together

A review requested by Morgan, with thanks to supporting Alternate Ending as a donor through Patreon.

Do you have a movie you'd like to see reviewed? This and other perks can be found on our Patreon page!

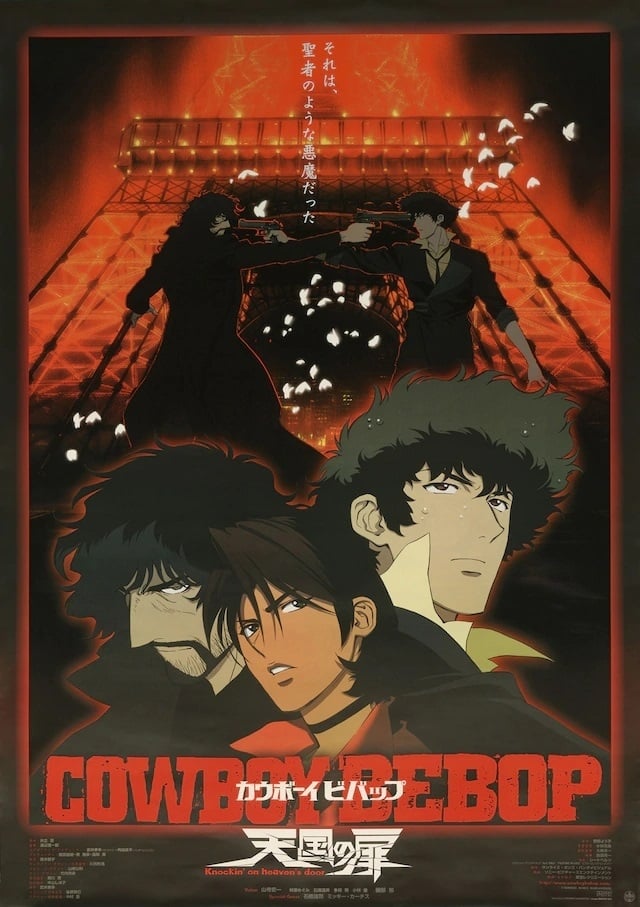

The first thing to say about the 2001 Japanese animated feature Cowboy Bebop: Knockin' on Heaven's Door (generally released in the West merely as Cowboy Bebop: The Movie, to avoid any possible scuffles with Bob Dylan's people) is that it inevitably lives in the shadow of the 1998-'99 Japanese animated television series Cowboy Bebop, though I don't think that should be any disincentive to see it. On the contrary, I think the movie has been crafted to be a very fine, comprehensible standalone object (to be fair, so were a good 75% of the show's episodes), and I might even go so far as to say that I think it might benefit from being watched that way. Taken on its own terms, this is a very impressive piece of animation and sci-fi worldbuilding, telling its gloomy story of a man-made end-times through some wonderfully expressive visuals and increasingly heavy atmosphere. As an episode of Cowboy Bebop, it's towards the bottom of my list, which certainly says more about the level the series had established for itself than it does about the movie. But them's the breaks.

Knockin' on Heaven's Door, as scripted by Nobumoto Keiko (who, like virtually everybody involved in the film's production, was part of the production staff of the show) opens with a scene perfectly calibrated to introduce the basics of the concept to people who hadn't watched the series while easing fans back into the vibes of this most vibe-driven of properties: in a convenience store nowhere in particular, a couple of criminals have been caught by a couple of bounty hunters, familiarly called "cowboys" in this setting: Spike Spiegel (Yamadera Koichi) and Jet Black (Ishizuka Unsho), the former of whom is callously cheerful, the latter of whom is obviously alarmed, even scared, by the Spike's impetuous, hotheaded decision to shoot the last crook even as he was holding an old woman hostage. And just like that, we have most of the important information we'll need from the show, all in a context that plays much more like a suspense sequence than a scene of exposition. Basically just like you'd anticipate from an episode of a show designed to be watched in any random order, which this mostly was, so I'm not sure why it impresses me so.

At any rate, this opening will end up informing basically nothing that happens for the rest of the movie's 115 minutes, so its purely mechanical function is hard to deny, but it doesn't remotely feel like that in the middle of watching it. I will absolutely not say that Knockin' on Heaven's Door uses that length (more than four episodes - the series had twice indulged in two-part stories, but nothing of this length) uses all of its time well, and in fact that's probably my single biggest complaint about the film, but in this particular case, I'm glad that the filmmakers gave themselves room to just dabble in a little disconnected moment, easing the viewer into the film's sarcastic, jazzy mode. It had, after all, been two years since the show went off the air, so even its fanbase could probably do with a bit of a warm-up, and the opening scene ends up being one of the film's stronger passages, focusing on workaday realism (there is no other location as deeply dull as that convenience store) to set off the sleek, cruelly cool attitude of our protagonist Spike, already suggesting something the film will tease out: he's a broken person who relies on a self-created image of himself whipped out of pop culture to stand out from the grotty world he is obliged to maneuver through. This was, to be sure, already something the series has teased out, and if I am going to be in the business of constantly comparing Knockin' on Heaven's Door to the original 26 episodes of Cowboy Bebop - and I at least wish I were better at not doing that - one of my bigger complaints is that this feels very redundant. It has to; though it's not fully serialised per se, there is a distinct arc to Cowboy Bebop and a pretty definitive ending, albeit one with some ragged edges that leave threads which could be tugged on. As such, Knockin' on Heaven's Door takes place within the series narrative: officially, between the 22nd and 23rd episodes, though I don't know that there's any unassailable reason it couldn't be placed a couple of episodes earlier. Regardless, the point is that there is a muted but consistent emotional arc through the show that grows more pronounced in its second half, and Knockin' on Heaven's Door can't do anything to trouble that arc. So basically, it's just "more of the same", and while that's a perfect agreeable thing for one out of 26 episodes of a television series to be, a feature-length film that goes to the trouble of revisiting that series feels like it ought to be "bigger", in some way. And there's really nothing about this that's "bigger", only "longer".

Even ignoring the series, "longer" isn't one of the film's strengths. There is certainly more story here than could fit into one episode, probably more than could fit into two, without trimming it down somewhat. But there is not enough story for 115 minutes, and this problem ends up being largely frontloaded: it's getting pretty close to the film's midway point before it finally starts to step on the accelerator, and most of what happens prior to that is a bunch of scenes of our main characters metaphorically poking under rocks to see if they can find any clues to the mystery of the week. It is, in effect, giving us a glimpse into what presumably happens on any TV show in the slower moments between plot beats, giving us a chance to watch the characters at their most quotidian and inactive. There's something interesting to that, conceptually, though I'll admit that I don't love watching it. But anyways, that mystery of the week: shortly before Halloween, 2071, a couple of hundred people in the largest city on Mars are taken down by a strange new disease, apparently spread by a terrorist attack; the unknown perpetrator of that attack is immediately tagged with the largest bounty in history. One of the very few people who might conceivably have any lead on the attacker is Faye Valentine (Hayashibara Megumi), the third bounty hunter scraping out an existence on Jet's ship, the Bebop, so the three of them - as well as the ship's resident hacker weirdo and precocious tween genius, Radical Ed (Tada Aoi), and the genetically augmented "data dog", Ein the corgi - decide that they might as well join everybody else in the galaxy in trying to find out what's going on.

And there we take a good long pause for the film to just simmer along slowly. None of what follows is "bad", but it's certainly not very exciting: lots of scenes of people looking furiously at computer screens and not moving; barely any music from Kanno Yoko's fantastic score of menacing electronica and space "Middle Eastern"-style cues (she is, more than anybody else, the reason Cowboy Bebop works - I don't even think that's a controversial opinion - and the first hour just doesn't "feel" right with actual rock songs replacing her jazzy cues). Eventually, they figure out that the terrorist is a man named Vincent (Isobe Tsutomu), who allegedly died in the wars some years ago, and they are then merely lucky as hell to cross paths with a woman named Elektra (Kobayashi Ai), the Dark Lady of Vincent's Past. And this is where "judging Knockin' on Heaven's Door as just a single movie" and "judging Knockin' on Heaven's Door as a delayed 27th episode of Cowboy Bebop" become two entirely different projects, and I am only a mortal and can only go so far in doing the former. Vincent is, by all means, a very good villain. He's presented, not explicitly, though I think you feel it pretty intuitively, as the mirror-Spike: damaged by his violent past, hung up on a woman whose presence would probably hurt just as much as her absence does, happy to operate on the fringes of the world, in the shadows and the grime. Within the context of these two hours - or, at least, within the context of the second hour, when the film begins to shift more cleanly into "Spike vs. Vincent" as its primary fuel - it's a well-built collision of emotional journeys, one leading Spike to the light and one leading Vincent to the darkness. Within the context of Cowboy Bebop, we already have a mirror-Spike, and he's much better at it.

That will, I promise, be the last negative comparison I make between the film and the show, because the worst one can say about Knockin' on Heaven's Door is that it's a much-too-long and somewhat redundant entry in one of the very best Japanese animated television series ever made, and the best is that it's an extremely stylish and appealing sci-fi animated feature with a great sense of apocalyptic gloom building as we get closer to Vincent and his desperate, hopeless rage. And in that respect, allow me to trot out a positive comparison between the two media: this is so much costlier than any given two hours of the show, and therefore so much more polished and ambitious and visually evocative. And Cowboy Bebop was already an exceptionally evocative show, sketching out one of the best "used futures" out there with its incredibly vivid background paintings. It's a world of specific Earth cultures that have retained their distinctive qualities while being homogenised by a century in which individual cultures seem to exist exclusively at the level of specific spaces, but not the human beings living there, who feel nomadic and thus pan-cultural. Knockin' on Heaven's Door adds an Arabian-ish setting to the show's ongoing civilisational sprawl, and the money the crew had meant that they could go on actual research trips to Arab world, which in turn means some of the most detailed, evocative settings the series ever enjoyed. And in addition to its generally excellent backgrounds, the movie follows the show in having some of the most jaw-dropping layouts you ever did see, dramatic noir-esque acute angles, startling juxtapositions of scale that emphasise the depth and enormous spaces of the world, striking angles on the heroes that make every beat of the action scenes feel like a selection of the most iconic comic book poses imaginable.

And then there's what the film adds that the show couldn't have. Lovely effects animation, for a start, including a motif of shining gold butterflies that builds up to a devastating shot during the final climax. But also, more simply, they can have more character animation. The film doesn't altogether abandoning the moderately-limited animation style typical of the show (and typical of a lot of TV animation, for that matter, especially in Japan): the fight scenes (of which there are fewer than one would like, particular in that leaden first hour) retain the distinct movement patterns from the fight scenes in the show, slightly slow repositioning of mostly static bodies that quickly shift into little flurries of quick movement for a few frames. But it does allow itself to indulge in more frames of animation where a TV show couldn't dare, to give us smaller and more nuanced facial expressions and emotional reactions. The three main characters of Cowboy Bebop already had some of my very favorite character design in the history of Japanese animation, and seeing those designs given more room to flex and breathe and express emotions is an extremely rewarding thing.

The film looks great, then, and it's superb at evoking an atmosphere if impending doom, both from its increasingly baroque angles and its pile-up of Halloween imagery the longer it goes on. Surprisingly - it surprises me, at least - this remains the sole theatrical feature directed by Watanabe Shinichiro, the head director of the series: he's more than demonstrated here that he understands how to use the larger canvas of a film screen and the greater affordances of a theatrical budget to amplify everything that was already working in the show and make it feel like a proper movie-scaled production. Which, all my grousing aside, this absolutely does: it's a beautifully weathered sci-fi setting with two hours devoted to settling into it, and a chance to see some of the best TV animation ever given an even better chance to shine than usual.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

Do you have a movie you'd like to see reviewed? This and other perks can be found on our Patreon page!

The first thing to say about the 2001 Japanese animated feature Cowboy Bebop: Knockin' on Heaven's Door (generally released in the West merely as Cowboy Bebop: The Movie, to avoid any possible scuffles with Bob Dylan's people) is that it inevitably lives in the shadow of the 1998-'99 Japanese animated television series Cowboy Bebop, though I don't think that should be any disincentive to see it. On the contrary, I think the movie has been crafted to be a very fine, comprehensible standalone object (to be fair, so were a good 75% of the show's episodes), and I might even go so far as to say that I think it might benefit from being watched that way. Taken on its own terms, this is a very impressive piece of animation and sci-fi worldbuilding, telling its gloomy story of a man-made end-times through some wonderfully expressive visuals and increasingly heavy atmosphere. As an episode of Cowboy Bebop, it's towards the bottom of my list, which certainly says more about the level the series had established for itself than it does about the movie. But them's the breaks.

Knockin' on Heaven's Door, as scripted by Nobumoto Keiko (who, like virtually everybody involved in the film's production, was part of the production staff of the show) opens with a scene perfectly calibrated to introduce the basics of the concept to people who hadn't watched the series while easing fans back into the vibes of this most vibe-driven of properties: in a convenience store nowhere in particular, a couple of criminals have been caught by a couple of bounty hunters, familiarly called "cowboys" in this setting: Spike Spiegel (Yamadera Koichi) and Jet Black (Ishizuka Unsho), the former of whom is callously cheerful, the latter of whom is obviously alarmed, even scared, by the Spike's impetuous, hotheaded decision to shoot the last crook even as he was holding an old woman hostage. And just like that, we have most of the important information we'll need from the show, all in a context that plays much more like a suspense sequence than a scene of exposition. Basically just like you'd anticipate from an episode of a show designed to be watched in any random order, which this mostly was, so I'm not sure why it impresses me so.

At any rate, this opening will end up informing basically nothing that happens for the rest of the movie's 115 minutes, so its purely mechanical function is hard to deny, but it doesn't remotely feel like that in the middle of watching it. I will absolutely not say that Knockin' on Heaven's Door uses that length (more than four episodes - the series had twice indulged in two-part stories, but nothing of this length) uses all of its time well, and in fact that's probably my single biggest complaint about the film, but in this particular case, I'm glad that the filmmakers gave themselves room to just dabble in a little disconnected moment, easing the viewer into the film's sarcastic, jazzy mode. It had, after all, been two years since the show went off the air, so even its fanbase could probably do with a bit of a warm-up, and the opening scene ends up being one of the film's stronger passages, focusing on workaday realism (there is no other location as deeply dull as that convenience store) to set off the sleek, cruelly cool attitude of our protagonist Spike, already suggesting something the film will tease out: he's a broken person who relies on a self-created image of himself whipped out of pop culture to stand out from the grotty world he is obliged to maneuver through. This was, to be sure, already something the series has teased out, and if I am going to be in the business of constantly comparing Knockin' on Heaven's Door to the original 26 episodes of Cowboy Bebop - and I at least wish I were better at not doing that - one of my bigger complaints is that this feels very redundant. It has to; though it's not fully serialised per se, there is a distinct arc to Cowboy Bebop and a pretty definitive ending, albeit one with some ragged edges that leave threads which could be tugged on. As such, Knockin' on Heaven's Door takes place within the series narrative: officially, between the 22nd and 23rd episodes, though I don't know that there's any unassailable reason it couldn't be placed a couple of episodes earlier. Regardless, the point is that there is a muted but consistent emotional arc through the show that grows more pronounced in its second half, and Knockin' on Heaven's Door can't do anything to trouble that arc. So basically, it's just "more of the same", and while that's a perfect agreeable thing for one out of 26 episodes of a television series to be, a feature-length film that goes to the trouble of revisiting that series feels like it ought to be "bigger", in some way. And there's really nothing about this that's "bigger", only "longer".

Even ignoring the series, "longer" isn't one of the film's strengths. There is certainly more story here than could fit into one episode, probably more than could fit into two, without trimming it down somewhat. But there is not enough story for 115 minutes, and this problem ends up being largely frontloaded: it's getting pretty close to the film's midway point before it finally starts to step on the accelerator, and most of what happens prior to that is a bunch of scenes of our main characters metaphorically poking under rocks to see if they can find any clues to the mystery of the week. It is, in effect, giving us a glimpse into what presumably happens on any TV show in the slower moments between plot beats, giving us a chance to watch the characters at their most quotidian and inactive. There's something interesting to that, conceptually, though I'll admit that I don't love watching it. But anyways, that mystery of the week: shortly before Halloween, 2071, a couple of hundred people in the largest city on Mars are taken down by a strange new disease, apparently spread by a terrorist attack; the unknown perpetrator of that attack is immediately tagged with the largest bounty in history. One of the very few people who might conceivably have any lead on the attacker is Faye Valentine (Hayashibara Megumi), the third bounty hunter scraping out an existence on Jet's ship, the Bebop, so the three of them - as well as the ship's resident hacker weirdo and precocious tween genius, Radical Ed (Tada Aoi), and the genetically augmented "data dog", Ein the corgi - decide that they might as well join everybody else in the galaxy in trying to find out what's going on.

And there we take a good long pause for the film to just simmer along slowly. None of what follows is "bad", but it's certainly not very exciting: lots of scenes of people looking furiously at computer screens and not moving; barely any music from Kanno Yoko's fantastic score of menacing electronica and space "Middle Eastern"-style cues (she is, more than anybody else, the reason Cowboy Bebop works - I don't even think that's a controversial opinion - and the first hour just doesn't "feel" right with actual rock songs replacing her jazzy cues). Eventually, they figure out that the terrorist is a man named Vincent (Isobe Tsutomu), who allegedly died in the wars some years ago, and they are then merely lucky as hell to cross paths with a woman named Elektra (Kobayashi Ai), the Dark Lady of Vincent's Past. And this is where "judging Knockin' on Heaven's Door as just a single movie" and "judging Knockin' on Heaven's Door as a delayed 27th episode of Cowboy Bebop" become two entirely different projects, and I am only a mortal and can only go so far in doing the former. Vincent is, by all means, a very good villain. He's presented, not explicitly, though I think you feel it pretty intuitively, as the mirror-Spike: damaged by his violent past, hung up on a woman whose presence would probably hurt just as much as her absence does, happy to operate on the fringes of the world, in the shadows and the grime. Within the context of these two hours - or, at least, within the context of the second hour, when the film begins to shift more cleanly into "Spike vs. Vincent" as its primary fuel - it's a well-built collision of emotional journeys, one leading Spike to the light and one leading Vincent to the darkness. Within the context of Cowboy Bebop, we already have a mirror-Spike, and he's much better at it.

That will, I promise, be the last negative comparison I make between the film and the show, because the worst one can say about Knockin' on Heaven's Door is that it's a much-too-long and somewhat redundant entry in one of the very best Japanese animated television series ever made, and the best is that it's an extremely stylish and appealing sci-fi animated feature with a great sense of apocalyptic gloom building as we get closer to Vincent and his desperate, hopeless rage. And in that respect, allow me to trot out a positive comparison between the two media: this is so much costlier than any given two hours of the show, and therefore so much more polished and ambitious and visually evocative. And Cowboy Bebop was already an exceptionally evocative show, sketching out one of the best "used futures" out there with its incredibly vivid background paintings. It's a world of specific Earth cultures that have retained their distinctive qualities while being homogenised by a century in which individual cultures seem to exist exclusively at the level of specific spaces, but not the human beings living there, who feel nomadic and thus pan-cultural. Knockin' on Heaven's Door adds an Arabian-ish setting to the show's ongoing civilisational sprawl, and the money the crew had meant that they could go on actual research trips to Arab world, which in turn means some of the most detailed, evocative settings the series ever enjoyed. And in addition to its generally excellent backgrounds, the movie follows the show in having some of the most jaw-dropping layouts you ever did see, dramatic noir-esque acute angles, startling juxtapositions of scale that emphasise the depth and enormous spaces of the world, striking angles on the heroes that make every beat of the action scenes feel like a selection of the most iconic comic book poses imaginable.

And then there's what the film adds that the show couldn't have. Lovely effects animation, for a start, including a motif of shining gold butterflies that builds up to a devastating shot during the final climax. But also, more simply, they can have more character animation. The film doesn't altogether abandoning the moderately-limited animation style typical of the show (and typical of a lot of TV animation, for that matter, especially in Japan): the fight scenes (of which there are fewer than one would like, particular in that leaden first hour) retain the distinct movement patterns from the fight scenes in the show, slightly slow repositioning of mostly static bodies that quickly shift into little flurries of quick movement for a few frames. But it does allow itself to indulge in more frames of animation where a TV show couldn't dare, to give us smaller and more nuanced facial expressions and emotional reactions. The three main characters of Cowboy Bebop already had some of my very favorite character design in the history of Japanese animation, and seeing those designs given more room to flex and breathe and express emotions is an extremely rewarding thing.

The film looks great, then, and it's superb at evoking an atmosphere if impending doom, both from its increasingly baroque angles and its pile-up of Halloween imagery the longer it goes on. Surprisingly - it surprises me, at least - this remains the sole theatrical feature directed by Watanabe Shinichiro, the head director of the series: he's more than demonstrated here that he understands how to use the larger canvas of a film screen and the greater affordances of a theatrical budget to amplify everything that was already working in the show and make it feel like a proper movie-scaled production. Which, all my grousing aside, this absolutely does: it's a beautifully weathered sci-fi setting with two hours devoted to settling into it, and a chance to see some of the best TV animation ever given an even better chance to shine than usual.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.