Archyology

A review requested by Devin, with thanks to supporting Alternate Ending as a donor through Patreon.

Do you have a movie you'd like to see reviewed? This and other perks can be found on our Patreon page!

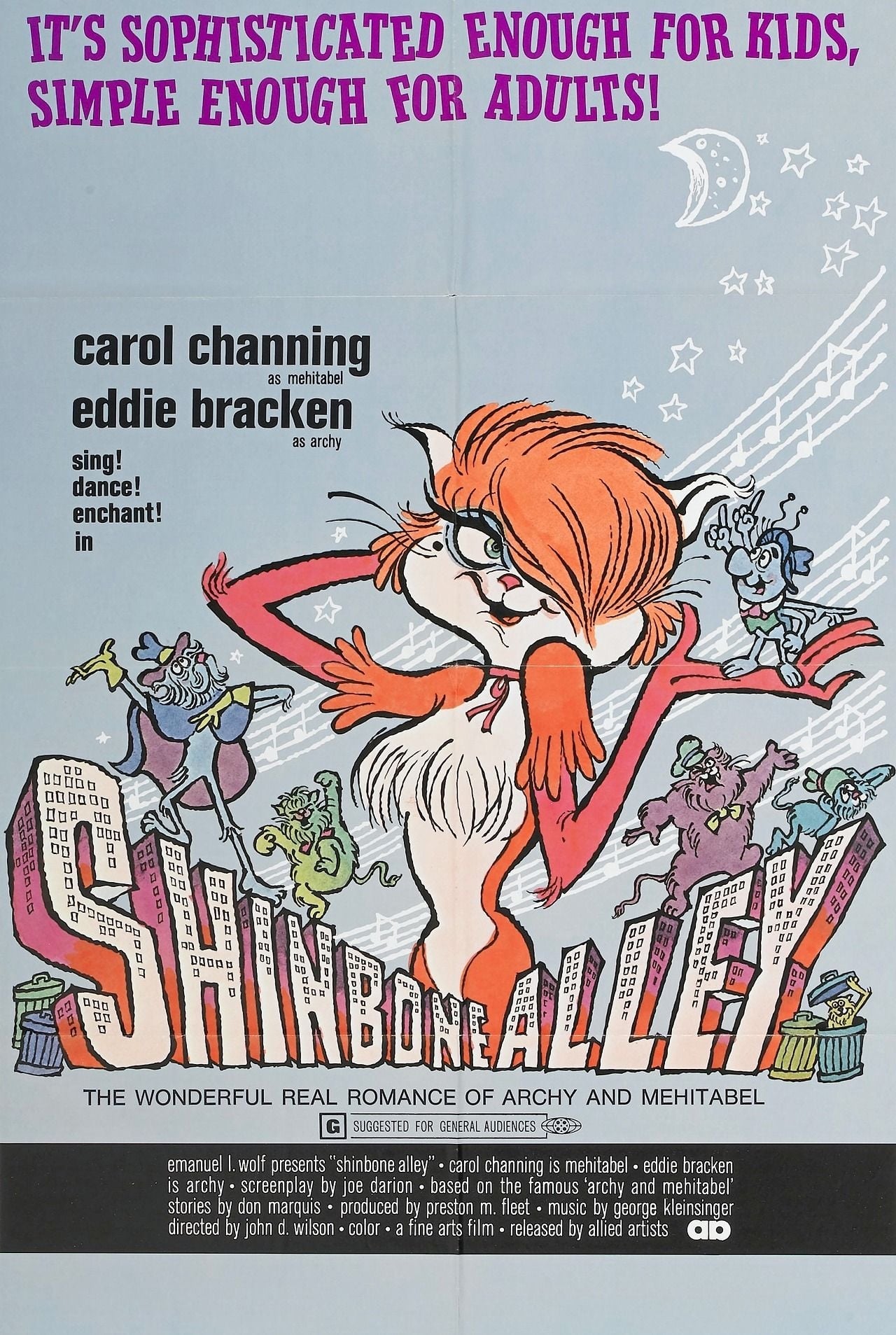

"It's sophisticated enough for children, simple enough for adults!" reads the tagline on the poster for the 1970 animated musical Shinbone Alley (which wasn't actually released until 1971). And while that's obviously meant to be knowing and clever, and I guess it is, in the brutish way of movie advertising copy, I think you can smell the desperation underneath the quipping. Shinbone Alley, you see, is a singular strange animated movie, trapped in the film marketplace of the early 1970s with absolutely nowhere to go, certainly no naturally-occurring audience. Undoubtedly for that exact reason, it sank without a ripple when it was first released, receiving mixed reviews along the way. For the critics didn't know what to make of it any more than viewers did.

We'll get back to that in a moment, because even a half-century later, I'm still not entirely sure how a film made of such competing, contradictory impulses could possibly have come into being, but for now let's pin down just what Shinbone Alley is. Its origins lie far back in the mists of American pop culture, all the way in 1916, at the typewriter of humorist and journalist Don Marquis, then working for the New York newspaper The Evening Sun. Here, Marquis concocted a strange little commentator, a cockroach poet and accomplished typist named archy. archy (his name spelled without capitals because he could not, being a cockroach, hold down the shift key on Marquis's typewriter) was a poet in a former life, reincarnated now in insect form, from which vantage point he offered lightly satiric observations on the world of New York in the '10s and '20s, often sharing stories of his dearest friend, the alley cat mehitabel. These essays and comic poems, often illustrated by Krazy Kat creator George Herriman, were a massive success, and the stories of archy and mehitabel remained a touchstone for New York literati for decades to come. Two of those literati, in the mid-'50s, were Joe Darion and Mel Brooks, who decided that the world was much in need of a musical based on Marquis's essays, and this resulted in the 1954 concept album archy & mehitabel, with a book by Darion & Brooks, lyrics by Darion, and music by George Kleinsinger. This in turn was expanded into a musical play, Shinbone Alley, that played on Broadway for about six weeks in the spring of 1957.

And there it lay, one of the countless musical flops that make up the history of the American musical theater, until Fine Arts Films decided to dredge it up and make a movie out of it. I imagine you have not heard of Fine Arts Films; I hadn't, at least. It was an animation company founded in 1955 by John David Wilson (Shinbone Alley's director), who believed in the potential of animation as a, well, fine art. I imagine Wilson was hoping to find space in the market for hip, stylistically complex animation for sophisticated adults that had recently been opened by United Productions of America; he had, in fact, worked for a short time at UPA, in addition to spending a couple of years at Disney immediately before founding his own studio. Despite the obscurity of the company, it was never without work, and was indeed called upon to provide relatively "hip" animation for various projects, for an extremely modest definition of "hip"; Wilson and Fine Arts provided animated sequences for The Sonny & Cher Comedy Hour and the opening credits sequence for the 1978 film Grease, so we're not exactly talking about the bleeding edge of the New York underground arts scene. At the same time, the animation was a bit rougher and more interesting than most of what you'd expect to find in the U.S. around the same time.

"Hip by square standards" is a pretty great way to start talking about Shinbone Alley itself; its broad confusion as to what exactly it's trying to be and who it's trying to be that way for manifests perhaps most strongly in its animation style. The overwhelming feeling one gets from watching this is that it's trying extremely hard to will Ralph Bakshi into existence, so it can crib from him: Fritz the Cat was still two years in the future, but Shinbone Alley feels uncannily like someone trying to make a watered-down version of that film's caustic vision of the admirable, disgusting lowlifes of New York, with a more audience-friendly aesthetic that share's Bakshi's roughly sketched-out lines but transmutes them into something with the simple broadness of Saturday morning cartoons. Whether that means that Bakshi had seen Shinbone Alley, I cannot begin to say. Regardless, that's the impression that just radiates right out of the film: what if Hanna-Barbera had made Fritz the Cat. It's a bit dizzying.

Not in a bad way! There's always an inherent interest in, and value to a piece of animation that pushes into some bold new direction, and I couldn't begin to tell you what, if any, animation prior to 1970 looked like this - and despite my Bakshi comparisons, I wouldn't entirely want to tell you that there was animation after 1970 that looked very much like this, either. It's a bit of an evolutionary dead end, probably because nobody in '71 had a clue what to do with it. The big-eyed, rounded character designs feel strictly kid's stuff, simple figures who look appealing in a very general way, and can be flexed in giant, exaggerated emotional states. And they've been drafted with an aggressive, scrawling style, and laid out against backgrounds that are full of heavy lines and crosshatches and thick swatches of color, real messy, urgent, edgy stuff. If it resembles anything, it's like Chuck Jones's work in the '60s but with a harsher, urban bent.

The story is every bit as weird and tangled up in incompatible impulses. The very first thing that happens is that the human who reincarnates as archy kills himself by jumping into the river - we don't see it directly, but it happens about two inches offscreen, and once we see the cockroach himself (voiced by Eddie Bracken, who recorded the role on the concept album and created the part onstage), he immediately confirms that's what just happened. So a suicide of despair, and then we're immediately into a cute little cartoon bug getting caught up in slapstick merriment. Shinbone Alley, bless its heart, genuinely believes that it's a family-friendly movie, because after all, talking animals and animation, that's kid's stuff, isn't it? And there was never a period in America where the "animation = children's media" was more broadly true than the end of the '60s and the '70s, but even so, the people putting this together surely didn't think that e.g. archy's hallucinatory dance with three ladybug prostitutes, writhing pornily as they sing, was exactly on par with, say, The Aristocats.

Still, there's something endearing about trying to force the story here about social outcasts bonding together and learning to celebrate their antisocial tendencies into the narrow channels of a children's comedy. The rest of the story follows archy's meeting with mehitabel (Carol Channing, who recorded the role on the concept album, but sat out the stage production; she was replaced by Eartha Kitt), becoming smitten with her lively rejection of the rules, but is concerned that she's going to wear herself out being used and abused by a succession of dubious tomcats: one a brutal, Stanley Kowalski-esque figure voiced by Alan Reed, mostly famous as Fred Flintstone, and my Christ, hearing Fred Flintstone as an abusive, sexually aggressive ruffian is as surreal as everything else about Shinbone Alley put together; another is a pretentious aging theater cat, voiced by John Carradine, who is having an unnervingly good time with all of the "me-ow" wordplay that Darion's lyrics have handed his way. Eventually, archy endeavors to have mehitabel safely brought into a human home, only to learn that it was her wild, dissolute ways that were the core part of her and the thing that made her happiest, and what made people love her, for one of the other things that Shinbone Alley specifically anticipates about Bakshi is its conviction that the most loutish, disreptuable, falling-apart drunk and oversexed gutter trash of New York are the only worthwhile and authentic people in that cesspit of a city.

Weird stuff for a kids' movie (I am, if nothing else, 100% confident that this was the first American animated feature in which one of the main characters has sex, gets pregnant, and gives birth, all out of wedlock, during the overall course of the narrative), and there's something irresistibly jarring in that mismatch between the dopey simplicity of the film's comedy and the thorny, mean streets filthiness of its plot, not to mention the sullen existentialism of archy's overall arc, and the generally moody songs (which are not, I would say, a strength: they're droning and unmemorable. At a minimum, the film leaves no surprise why the show flopped). The whole film puts rancid, caustic cynicism and bright cartoon hijinks next to each other, and it never seems to realise that they're in any way in conflict, so it never tries to bring them in balance. This doesn't always work out to the film's benefit: it slops about drunkenly from tone to tone, and the more broadly comic it gets, the more sloppy. So the whole thing, even at just 84 minutes, has a lot of shapeless, draggy patches, a feeling not at all helped out by how little actual story there is in the first half. Granting that though, and acknowledge that Shinbone Alley is more of a Bizarro World curiosity than a lost classic, this is a remarkable, one-of-a-kind experience, and surely one of the most striking and surprising pieces of American animation from the dead zone between Walt Disney's death and the late '80s.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

Do you have a movie you'd like to see reviewed? This and other perks can be found on our Patreon page!

"It's sophisticated enough for children, simple enough for adults!" reads the tagline on the poster for the 1970 animated musical Shinbone Alley (which wasn't actually released until 1971). And while that's obviously meant to be knowing and clever, and I guess it is, in the brutish way of movie advertising copy, I think you can smell the desperation underneath the quipping. Shinbone Alley, you see, is a singular strange animated movie, trapped in the film marketplace of the early 1970s with absolutely nowhere to go, certainly no naturally-occurring audience. Undoubtedly for that exact reason, it sank without a ripple when it was first released, receiving mixed reviews along the way. For the critics didn't know what to make of it any more than viewers did.

We'll get back to that in a moment, because even a half-century later, I'm still not entirely sure how a film made of such competing, contradictory impulses could possibly have come into being, but for now let's pin down just what Shinbone Alley is. Its origins lie far back in the mists of American pop culture, all the way in 1916, at the typewriter of humorist and journalist Don Marquis, then working for the New York newspaper The Evening Sun. Here, Marquis concocted a strange little commentator, a cockroach poet and accomplished typist named archy. archy (his name spelled without capitals because he could not, being a cockroach, hold down the shift key on Marquis's typewriter) was a poet in a former life, reincarnated now in insect form, from which vantage point he offered lightly satiric observations on the world of New York in the '10s and '20s, often sharing stories of his dearest friend, the alley cat mehitabel. These essays and comic poems, often illustrated by Krazy Kat creator George Herriman, were a massive success, and the stories of archy and mehitabel remained a touchstone for New York literati for decades to come. Two of those literati, in the mid-'50s, were Joe Darion and Mel Brooks, who decided that the world was much in need of a musical based on Marquis's essays, and this resulted in the 1954 concept album archy & mehitabel, with a book by Darion & Brooks, lyrics by Darion, and music by George Kleinsinger. This in turn was expanded into a musical play, Shinbone Alley, that played on Broadway for about six weeks in the spring of 1957.

And there it lay, one of the countless musical flops that make up the history of the American musical theater, until Fine Arts Films decided to dredge it up and make a movie out of it. I imagine you have not heard of Fine Arts Films; I hadn't, at least. It was an animation company founded in 1955 by John David Wilson (Shinbone Alley's director), who believed in the potential of animation as a, well, fine art. I imagine Wilson was hoping to find space in the market for hip, stylistically complex animation for sophisticated adults that had recently been opened by United Productions of America; he had, in fact, worked for a short time at UPA, in addition to spending a couple of years at Disney immediately before founding his own studio. Despite the obscurity of the company, it was never without work, and was indeed called upon to provide relatively "hip" animation for various projects, for an extremely modest definition of "hip"; Wilson and Fine Arts provided animated sequences for The Sonny & Cher Comedy Hour and the opening credits sequence for the 1978 film Grease, so we're not exactly talking about the bleeding edge of the New York underground arts scene. At the same time, the animation was a bit rougher and more interesting than most of what you'd expect to find in the U.S. around the same time.

"Hip by square standards" is a pretty great way to start talking about Shinbone Alley itself; its broad confusion as to what exactly it's trying to be and who it's trying to be that way for manifests perhaps most strongly in its animation style. The overwhelming feeling one gets from watching this is that it's trying extremely hard to will Ralph Bakshi into existence, so it can crib from him: Fritz the Cat was still two years in the future, but Shinbone Alley feels uncannily like someone trying to make a watered-down version of that film's caustic vision of the admirable, disgusting lowlifes of New York, with a more audience-friendly aesthetic that share's Bakshi's roughly sketched-out lines but transmutes them into something with the simple broadness of Saturday morning cartoons. Whether that means that Bakshi had seen Shinbone Alley, I cannot begin to say. Regardless, that's the impression that just radiates right out of the film: what if Hanna-Barbera had made Fritz the Cat. It's a bit dizzying.

Not in a bad way! There's always an inherent interest in, and value to a piece of animation that pushes into some bold new direction, and I couldn't begin to tell you what, if any, animation prior to 1970 looked like this - and despite my Bakshi comparisons, I wouldn't entirely want to tell you that there was animation after 1970 that looked very much like this, either. It's a bit of an evolutionary dead end, probably because nobody in '71 had a clue what to do with it. The big-eyed, rounded character designs feel strictly kid's stuff, simple figures who look appealing in a very general way, and can be flexed in giant, exaggerated emotional states. And they've been drafted with an aggressive, scrawling style, and laid out against backgrounds that are full of heavy lines and crosshatches and thick swatches of color, real messy, urgent, edgy stuff. If it resembles anything, it's like Chuck Jones's work in the '60s but with a harsher, urban bent.

The story is every bit as weird and tangled up in incompatible impulses. The very first thing that happens is that the human who reincarnates as archy kills himself by jumping into the river - we don't see it directly, but it happens about two inches offscreen, and once we see the cockroach himself (voiced by Eddie Bracken, who recorded the role on the concept album and created the part onstage), he immediately confirms that's what just happened. So a suicide of despair, and then we're immediately into a cute little cartoon bug getting caught up in slapstick merriment. Shinbone Alley, bless its heart, genuinely believes that it's a family-friendly movie, because after all, talking animals and animation, that's kid's stuff, isn't it? And there was never a period in America where the "animation = children's media" was more broadly true than the end of the '60s and the '70s, but even so, the people putting this together surely didn't think that e.g. archy's hallucinatory dance with three ladybug prostitutes, writhing pornily as they sing, was exactly on par with, say, The Aristocats.

Still, there's something endearing about trying to force the story here about social outcasts bonding together and learning to celebrate their antisocial tendencies into the narrow channels of a children's comedy. The rest of the story follows archy's meeting with mehitabel (Carol Channing, who recorded the role on the concept album, but sat out the stage production; she was replaced by Eartha Kitt), becoming smitten with her lively rejection of the rules, but is concerned that she's going to wear herself out being used and abused by a succession of dubious tomcats: one a brutal, Stanley Kowalski-esque figure voiced by Alan Reed, mostly famous as Fred Flintstone, and my Christ, hearing Fred Flintstone as an abusive, sexually aggressive ruffian is as surreal as everything else about Shinbone Alley put together; another is a pretentious aging theater cat, voiced by John Carradine, who is having an unnervingly good time with all of the "me-ow" wordplay that Darion's lyrics have handed his way. Eventually, archy endeavors to have mehitabel safely brought into a human home, only to learn that it was her wild, dissolute ways that were the core part of her and the thing that made her happiest, and what made people love her, for one of the other things that Shinbone Alley specifically anticipates about Bakshi is its conviction that the most loutish, disreptuable, falling-apart drunk and oversexed gutter trash of New York are the only worthwhile and authentic people in that cesspit of a city.

Weird stuff for a kids' movie (I am, if nothing else, 100% confident that this was the first American animated feature in which one of the main characters has sex, gets pregnant, and gives birth, all out of wedlock, during the overall course of the narrative), and there's something irresistibly jarring in that mismatch between the dopey simplicity of the film's comedy and the thorny, mean streets filthiness of its plot, not to mention the sullen existentialism of archy's overall arc, and the generally moody songs (which are not, I would say, a strength: they're droning and unmemorable. At a minimum, the film leaves no surprise why the show flopped). The whole film puts rancid, caustic cynicism and bright cartoon hijinks next to each other, and it never seems to realise that they're in any way in conflict, so it never tries to bring them in balance. This doesn't always work out to the film's benefit: it slops about drunkenly from tone to tone, and the more broadly comic it gets, the more sloppy. So the whole thing, even at just 84 minutes, has a lot of shapeless, draggy patches, a feeling not at all helped out by how little actual story there is in the first half. Granting that though, and acknowledge that Shinbone Alley is more of a Bizarro World curiosity than a lost classic, this is a remarkable, one-of-a-kind experience, and surely one of the most striking and surprising pieces of American animation from the dead zone between Walt Disney's death and the late '80s.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.