Blockbuster History: The Crimes of David Cronenberg

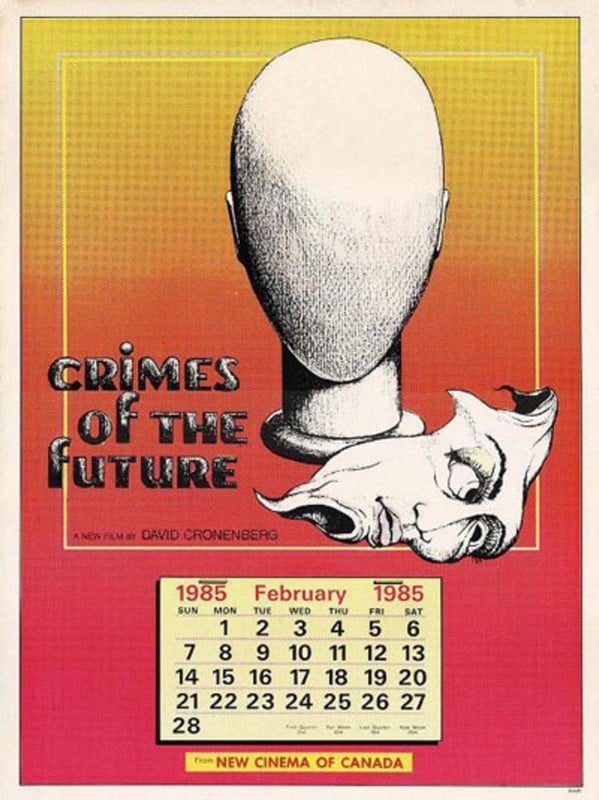

Every week this summer, we'll be taking an historical tour of the Hollywood blockbuster by examining an older film that is in some way a spiritual precursor to one of the weekend's wide releases. Last week: David Cronenberg, in his years as an elder statesman of cinema, has taken the new Crimes of the Future as an opportunity to go back to his years as a brash kid. I cannot think of a better place to journey with him than to the movie that gave his new feature its title.

The critic and genre historian Kim Newman, in his 1988 book Nightmare Movies, delivered a verdict on director David Cronenberg's first two features so definitive that one struggles to find a single word to add: 1969's Stereo and 1970's Crimes of the Future prove that "it's possible to be boring and interesting at the same time". That's an incredibly keen description of the peculiar effect produced by both of those movies, and perhaps Crimes of the Future even moreso than Stereo; Crimes is both the more interesting and the more boring of the two acutely similar films.

Both of these films come at a point when Cronenberg's identity as a filmmaker was tenuous and amorphous; I very nearly said his "career" as a filmmaker, but that's almost the point, he had no such career at this point. Famously (at least, famously to the kind of people who collect biographical details of massively beloved cult filmmakers), Cronenberg did not enter the University of Toronto to study film, but science; it was only most of the way through his undergraduate career that he switched focus, producing while still a student a pair of esoteric short films pointedly aping the underground avant-garde movements then burgeoning on the east and west coasts of the United States. His first two longform projects, though made after he graduated, were still very much in that mode; having called them "features", as one more or less has to given their length (both are about 63 minutes), I concede that there's no real possibility that either of them was even slightly designed to live in the commercial film marketplace. These are unmistakable experimental films, made up of opaque scripts applied to even more opaque imagery, and what exactly they were meant to do for the young Cronenberg, I cannot say; somehow, they managed to function as calling cards, and he made several short documentaries and and narrative films for Canadian television over the next few years, before finally making his relatively "mainstream" debut in 1975 with the horror movie Shivers, given a sufficiently flexible definition of "mainstream" that includes a film so grotesque and revolting to the sensibilities of the Canadian critics and industry that the national government (which was involved in its funding) was pulled into a debate over whether it had sufficient artistic merit to be socially permissible.

We're not there yet; Crimes of the Future is such a small, defiantly offbeat production for such a niche audience that I cannot imagine what meager percentage of Canadian citizens in 1970 would have even heard of it. It and Stereo were both made according to essentially the same formula: Cronenberg, working as most of his own crew, filmed several of his friends, led by Ronald Mlodzik, as they enacted weird tableaux in and around an imposing new Brutalist structure, in this case the Ontario Science Centre in Toronto, which was only completed in the late summer of 1969. This footage was recorded without sound, and voiceover narration was added to suggest that the final edit was in some fashion a scientific relic. For Stereo, it was the recorded notes of several scientists conducting experiments on the link between telepathy, sexuality, and the embodied consciousness; in Crimes of the Future, it's less of a research program than a memoir, as Adrian Tripod (emphasis very fussily placed on the second syllable), voiced and played by Mlodzik, recounts his effort to find his lost mentor, the insane dermatologist Antoine Rouge. It's also Tripod's account of the state of the world after a plague was wiped out the entire population of all the women in the world who have gone through puberty, thanks to some kind of engineered plague transmitted through cosmetics, and in some way connected to Rouge himself; also, there are indications that the plague might have mutated (or been mutated) to affect males as well, with Rouge the first victim.

The overall vibe is of the driest deadpan humor, so dry that I truthfully cannot imagine the viewer who would find it actually funny. But it's also impossible to take it seriously, and the film is not asking that we do so. It exists in a wholly conceptual state, where the point of the thing is that thing itself is a ridiculous, off-putting object. It's a parody of scientific observation and careful log-keeping that has been dragged out to such an incredible length for such a flat joke that the frustration feels like it's all part of the game.

So, back we go to Newman: it is boring. What, then, makes it interesting? Plenty of that, to be sure, is strictly historical and assisted by hindsight, and strictly for people with a vested interested in crawling through the dark places where Cronenberg came from, en route to become one of the most famous and/or infamous directors of disturbingly sexualised horror of the latter half of the 20th Century. And I say "one of" to cover my ass, but I can't really think of any filmmaker who would be more associated with the free mixture of sex, body horror, fetishes, and remarkable cinematic know-how than Cronenberg. Crimes of the Future doesn't exactly show off cinematic know-how; in fact, I think it is somewhat less interesting as a movie qua movies than Stereo, which at least was filmed in stark, excitingly sharp black-and-white. Cronenberg was able to pull together enough money this time around to shoot on color stock, but I'm not sure it's of any particular benefit, give or take a few late scenes where he's found an interesting wall of primary-colored glass panes to stage Mlodzik in front of. Mostly, it just shows off how drably grey the Ontario Science Centre was, and not in the excitingly alien manner of Stereo; just in the "oof, modernism was really starting to run out of gas in '69 and '70, wasn't it?" way. There are individual shots throughout Crimes of the Future that are very striking indeed, of which my favorite is probably a shot positioned just so at the end of a flight of stairs that it takes your brain a good long beat to determine if you're looking down or up, and the every-which-way nature of the concrete walls around those stairs don't help to give it context. There's a sense of disorientation that crops up here and a few other spots in the movie, making the most of the eerie placelessness of the building, which is called upon to play several different locations, and it's pretty great how the movie blurs the line between one location doing a ton of work, and several locations that all feel uncomfortably blurred together in a future that has given up all hope and humanity.

Again, that happens in individual moments; the whole thing feels much more like a random collection of images that don't accumulate any meaning. In Stereo, the narration kind of forced a reading onto the footage, and that doesn't really happen in Crimes of the Future; I'm honestly not sure if I prefer one to the other, because in both cases it's slightly dull and pretentious either way. It's difficult to tell if there was any particular shooting plan in place, or if Cronenberg and his cast just found interesting locations and did something there; by the time the story reaches its climax - and it does, in fact, have a pretty clear-cut story, one that is almost entirely communicated through the narration until around the 40-minute mark - it's clear that shots have been planned to have meaning, but the most one can say about the bulk of the movie is that it seems to be gathered around a set of shared motifs. Mostly, this means a lot of homoerotic beats, with the implication seeming to be that a world with no women is necessarily a world of homosexuals, and I am at a complete loss to determine whether this is something Cronenberg and the film find unnerving or not. But that's kind of the pleasure of watching this director's films: the extremely messy boundaries between "gruesome perversity" and "healthy sexuality" that he manages to set up, and very infrequently where you would expect them to be. The androgyny that's present in scene after scene of Crimes of the Future is certainly depicted as something strange and discomfiting, but only because literally everything in the film is strange and discomfiting, while the real horror of the scenario is held off for a mysterious group of mad scientists attempting to create a neo-heterosexuality of sorts.

All of which ties us into something else Newman said: it's more interesting to hear about Crimes of the Future than it is to watch it. Everything I've just said is true and all, but it's sort of inert watching it happen onscreen, and the narration doesn't really do anything to the images other than provide an entirely different narrative experience that somewhat flattens the entire image track into "some weird stuff in a hallucinatory ugly building". The film's sound effects (not found in Stereo, which had literally no sound other than narration) somewhat tie the two elements of the film together, and I'd almost go so far as to call them the most effective part of the movie: they create a disturbing imbalance that makes things rather tenser than the rather flatly "this is an art film" feeling of the cinematography does. Still, it's not enough to actually make Crimes of the Future an engaging thing to watch; it's just one more array of Stuff in a film that has too much Stuff and not enough conscious assembly as it is. It's more than fascinating as a germinal form of Cronenberg's interest in sex, repressed sexuality, and dysfunctional societies encourage repressed sexuality, but it's not really fascinating as a movie in its own right. I'm not one to say "thank God he sold out and started making mainstream genre films", but frankly, I don't think that the Cronenberg who kept on this path is a Cronenberg we'd be talking about a half-century later.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

If you enjoyed this article, why not support Alternate Ending as a recurring donor through Patreon, or with a one-time donation via Paypal? For just a dollar a month you can contribute to the ongoing health of the site, while also enjoying several fun perks!

The critic and genre historian Kim Newman, in his 1988 book Nightmare Movies, delivered a verdict on director David Cronenberg's first two features so definitive that one struggles to find a single word to add: 1969's Stereo and 1970's Crimes of the Future prove that "it's possible to be boring and interesting at the same time". That's an incredibly keen description of the peculiar effect produced by both of those movies, and perhaps Crimes of the Future even moreso than Stereo; Crimes is both the more interesting and the more boring of the two acutely similar films.

Both of these films come at a point when Cronenberg's identity as a filmmaker was tenuous and amorphous; I very nearly said his "career" as a filmmaker, but that's almost the point, he had no such career at this point. Famously (at least, famously to the kind of people who collect biographical details of massively beloved cult filmmakers), Cronenberg did not enter the University of Toronto to study film, but science; it was only most of the way through his undergraduate career that he switched focus, producing while still a student a pair of esoteric short films pointedly aping the underground avant-garde movements then burgeoning on the east and west coasts of the United States. His first two longform projects, though made after he graduated, were still very much in that mode; having called them "features", as one more or less has to given their length (both are about 63 minutes), I concede that there's no real possibility that either of them was even slightly designed to live in the commercial film marketplace. These are unmistakable experimental films, made up of opaque scripts applied to even more opaque imagery, and what exactly they were meant to do for the young Cronenberg, I cannot say; somehow, they managed to function as calling cards, and he made several short documentaries and and narrative films for Canadian television over the next few years, before finally making his relatively "mainstream" debut in 1975 with the horror movie Shivers, given a sufficiently flexible definition of "mainstream" that includes a film so grotesque and revolting to the sensibilities of the Canadian critics and industry that the national government (which was involved in its funding) was pulled into a debate over whether it had sufficient artistic merit to be socially permissible.

We're not there yet; Crimes of the Future is such a small, defiantly offbeat production for such a niche audience that I cannot imagine what meager percentage of Canadian citizens in 1970 would have even heard of it. It and Stereo were both made according to essentially the same formula: Cronenberg, working as most of his own crew, filmed several of his friends, led by Ronald Mlodzik, as they enacted weird tableaux in and around an imposing new Brutalist structure, in this case the Ontario Science Centre in Toronto, which was only completed in the late summer of 1969. This footage was recorded without sound, and voiceover narration was added to suggest that the final edit was in some fashion a scientific relic. For Stereo, it was the recorded notes of several scientists conducting experiments on the link between telepathy, sexuality, and the embodied consciousness; in Crimes of the Future, it's less of a research program than a memoir, as Adrian Tripod (emphasis very fussily placed on the second syllable), voiced and played by Mlodzik, recounts his effort to find his lost mentor, the insane dermatologist Antoine Rouge. It's also Tripod's account of the state of the world after a plague was wiped out the entire population of all the women in the world who have gone through puberty, thanks to some kind of engineered plague transmitted through cosmetics, and in some way connected to Rouge himself; also, there are indications that the plague might have mutated (or been mutated) to affect males as well, with Rouge the first victim.

The overall vibe is of the driest deadpan humor, so dry that I truthfully cannot imagine the viewer who would find it actually funny. But it's also impossible to take it seriously, and the film is not asking that we do so. It exists in a wholly conceptual state, where the point of the thing is that thing itself is a ridiculous, off-putting object. It's a parody of scientific observation and careful log-keeping that has been dragged out to such an incredible length for such a flat joke that the frustration feels like it's all part of the game.

So, back we go to Newman: it is boring. What, then, makes it interesting? Plenty of that, to be sure, is strictly historical and assisted by hindsight, and strictly for people with a vested interested in crawling through the dark places where Cronenberg came from, en route to become one of the most famous and/or infamous directors of disturbingly sexualised horror of the latter half of the 20th Century. And I say "one of" to cover my ass, but I can't really think of any filmmaker who would be more associated with the free mixture of sex, body horror, fetishes, and remarkable cinematic know-how than Cronenberg. Crimes of the Future doesn't exactly show off cinematic know-how; in fact, I think it is somewhat less interesting as a movie qua movies than Stereo, which at least was filmed in stark, excitingly sharp black-and-white. Cronenberg was able to pull together enough money this time around to shoot on color stock, but I'm not sure it's of any particular benefit, give or take a few late scenes where he's found an interesting wall of primary-colored glass panes to stage Mlodzik in front of. Mostly, it just shows off how drably grey the Ontario Science Centre was, and not in the excitingly alien manner of Stereo; just in the "oof, modernism was really starting to run out of gas in '69 and '70, wasn't it?" way. There are individual shots throughout Crimes of the Future that are very striking indeed, of which my favorite is probably a shot positioned just so at the end of a flight of stairs that it takes your brain a good long beat to determine if you're looking down or up, and the every-which-way nature of the concrete walls around those stairs don't help to give it context. There's a sense of disorientation that crops up here and a few other spots in the movie, making the most of the eerie placelessness of the building, which is called upon to play several different locations, and it's pretty great how the movie blurs the line between one location doing a ton of work, and several locations that all feel uncomfortably blurred together in a future that has given up all hope and humanity.

Again, that happens in individual moments; the whole thing feels much more like a random collection of images that don't accumulate any meaning. In Stereo, the narration kind of forced a reading onto the footage, and that doesn't really happen in Crimes of the Future; I'm honestly not sure if I prefer one to the other, because in both cases it's slightly dull and pretentious either way. It's difficult to tell if there was any particular shooting plan in place, or if Cronenberg and his cast just found interesting locations and did something there; by the time the story reaches its climax - and it does, in fact, have a pretty clear-cut story, one that is almost entirely communicated through the narration until around the 40-minute mark - it's clear that shots have been planned to have meaning, but the most one can say about the bulk of the movie is that it seems to be gathered around a set of shared motifs. Mostly, this means a lot of homoerotic beats, with the implication seeming to be that a world with no women is necessarily a world of homosexuals, and I am at a complete loss to determine whether this is something Cronenberg and the film find unnerving or not. But that's kind of the pleasure of watching this director's films: the extremely messy boundaries between "gruesome perversity" and "healthy sexuality" that he manages to set up, and very infrequently where you would expect them to be. The androgyny that's present in scene after scene of Crimes of the Future is certainly depicted as something strange and discomfiting, but only because literally everything in the film is strange and discomfiting, while the real horror of the scenario is held off for a mysterious group of mad scientists attempting to create a neo-heterosexuality of sorts.

All of which ties us into something else Newman said: it's more interesting to hear about Crimes of the Future than it is to watch it. Everything I've just said is true and all, but it's sort of inert watching it happen onscreen, and the narration doesn't really do anything to the images other than provide an entirely different narrative experience that somewhat flattens the entire image track into "some weird stuff in a hallucinatory ugly building". The film's sound effects (not found in Stereo, which had literally no sound other than narration) somewhat tie the two elements of the film together, and I'd almost go so far as to call them the most effective part of the movie: they create a disturbing imbalance that makes things rather tenser than the rather flatly "this is an art film" feeling of the cinematography does. Still, it's not enough to actually make Crimes of the Future an engaging thing to watch; it's just one more array of Stuff in a film that has too much Stuff and not enough conscious assembly as it is. It's more than fascinating as a germinal form of Cronenberg's interest in sex, repressed sexuality, and dysfunctional societies encourage repressed sexuality, but it's not really fascinating as a movie in its own right. I'm not one to say "thank God he sold out and started making mainstream genre films", but frankly, I don't think that the Cronenberg who kept on this path is a Cronenberg we'd be talking about a half-century later.

Tim Brayton is the editor-in-chief and primary critic at Alternate Ending. He has been known to show up on Letterboxd, writing about even more movies than he does here.

If you enjoyed this article, why not support Alternate Ending as a recurring donor through Patreon, or with a one-time donation via Paypal? For just a dollar a month you can contribute to the ongoing health of the site, while also enjoying several fun perks!