Get off the bus

A review requested by Martha, with thanks to supporting Alternate Ending as a donor through Patreon.

Do you have a movie you'd like to see reviewed? This and other perks can be found on our Patreon page!

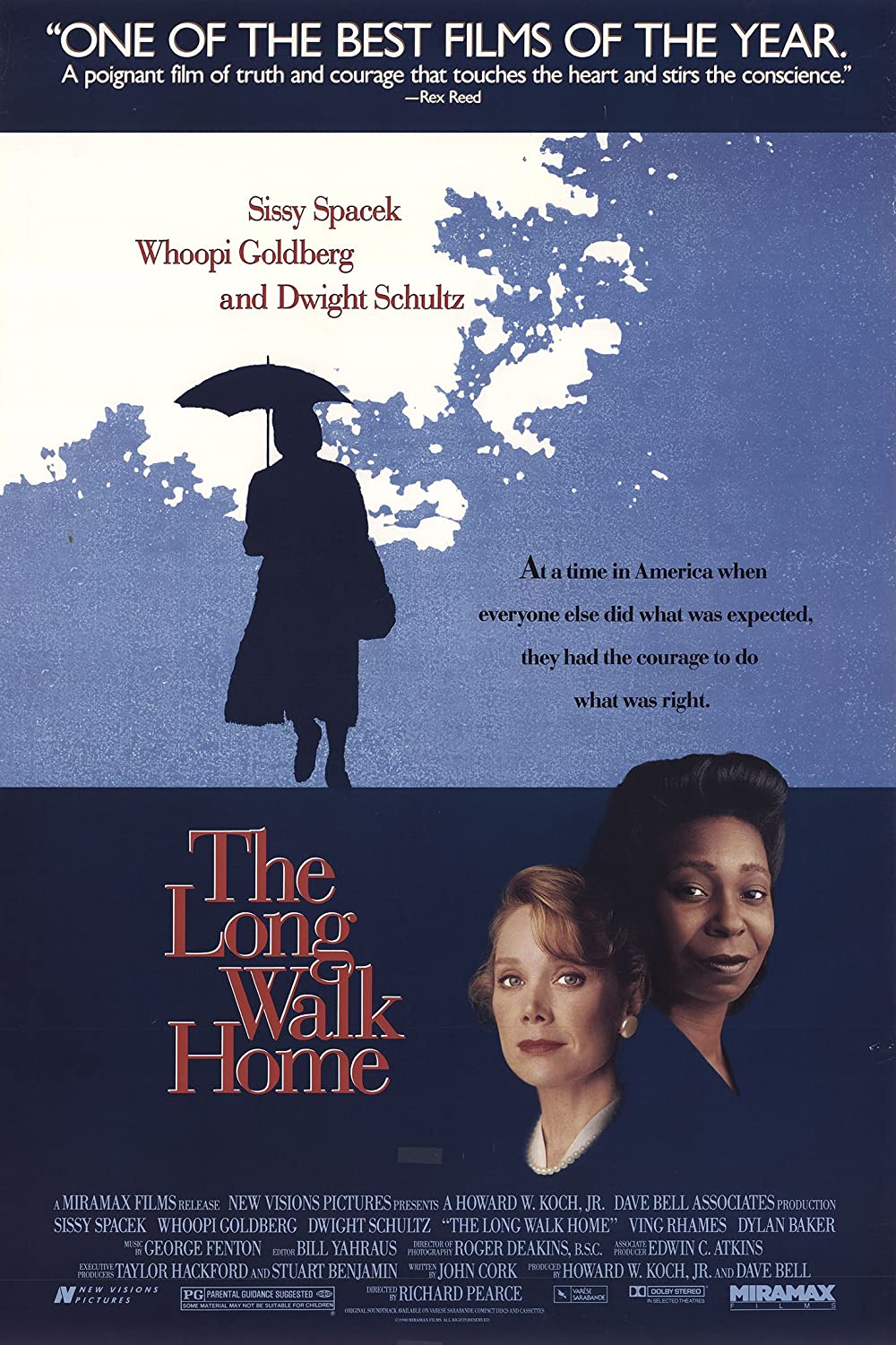

There aren't too many formulations that make me instantaneously suspicious of a movie more than A) a story about historical racism in the United States, B) with a release strategy that clearly indicates they were sniffing for some Academy Awards (in this case, New York and Los Angeles on 21 December 1990, delayed in the rest of the country until 22 March 1991), C) with more white people than African-Americans in the top-line cast, D) from the 1980s or early 1990s. That I still ended up finding some real value in The Long Walk Home is genuinely surprising to me: it's not a perfect movie by any stretch of the imagination, but it's honestly a lot more thoughtful about how it wants to tell a story of the Montgomery, AL bus boycott of 1955-'56 than I would have expected, and it tackles one of the biggest problems this kind of story is likely to face head-on. Or, if not quite head-on, in the end, at least from a fairly steep angle.

That problem being the annoying tendency for films about racism to actually be about white people who are sad about racism, or who learn to be sad about racism. In this case, that white person is Miriam Thompson (Sissy Spacek), a housewife with who lives comfortably with her two daughters, Mary Catherine (Lexi Randall) and Sara (Crystal Robbins), and a meek husband, Norman (Dwight Schultz, who got an above-the-title credit despite being best-known as the lead of The A-Team that you need to really stop and think about after you've already come up with Mr. T, George Peppard, and Dirk Benedict. That's how you know this is an indie movie). They are thoroughly unremarkable members of Montogomery's upper-middle-class, and like everyone else in that class, they have a Black maid, Odessa Cotter (Whoopi Goldberg), who has to take the bus to the Thompson house every day. And so it continues until 5 December, 1955, when Montgomery's African-American population boycotts the city's bus system in protest of the arrest of Rosa Parks a few days earlier. This is a major upheaval for the entire city for a multitude of reasons, but the one we care about the most is that Odessa now has a hell of a long way to walk to and from her job at the Thompsons' place, and it very quickly starts to wear her body down to go along with the deep misery of her heart.

A couple of things to pull out of there right away. First, if you noticed how that précis starts on Miriam and ends on Odessa, then you have grasped the structural clunkiness that The Long Walk Home hasn't figured out how to solve, or has figured out and doesn't want to solve. Related to that, if you noticed that I didn't list out Odessa's family members - she has a matched set to balance Miriam's, including Ving Rhames as her husband - then you have grasped one specific way that the clunky structure manifests itself.

As written by John Cork, for whom this is a very lightly autobiographical effort (as a child, he would have been analogous to Mary Catherine, who narrates the first and last scenes of the film as an adult, in the voice of Mary Steenburgen), The Long Walk Home is split pretty close to write down the middle between Miriam and Odessa. Spacek is top-billed; if I were forced to guess without having timed it, I think Goldberg probably has slightly more screentime. Either way, the film works hard to balance itself as the story of two women who experienced the Montgomery bus boycott from two very different directions. And I do mean hard: it never comes organically. And these two stories are not created equal: Odessa's experience, which involves slightly reluctant solidarity with her community that very quickly turns into real activist commitment, is self-evidently the more intellectually gratifying approach, since it understands the boycott as a purposeful, material thing, a matter of difficult choices and political strategies, and the expression of a community that we see portrayed over and over again in the film in huge group shots and very geometrically-precise church interiors. Richard Pearce is not a director who has much in the way of a notable career, but he's given some very clear thought to how to visually distinguish the two racial worlds in the film, and this invariably favors the African-American communities, who feel like they have been worked into a distinct visual strategy, rather than the white people who are just kind of lumped into by-the-books late-'80s prestige filmmaking. It doesn't hurt that Pearce has a ringer of a cinematographer in the form of Roger Deakins (whose very next film would be the career-making Barton Fink) who isn't doing anything particularly showy here, but who does remarkable, nuanced work in modulating the amount of diffuse sunshine to give different parts of Montgomery some very different visual characteristics, and always with a slightly darker, more realistic foundation that I am used to from this era of middlebrow message films.

So the film tends to stylistically favor Odessa (this is also true, by the way, of George Fenton's gooey, tackily sentimental score; I do not at all care for it, but it is interesting that it's really only activating itself in scenes about Black people). And because of this, it seems to understand that the story of the bus boycott really does need to be told via the people doing the boycott, with an eye on what it cost them - in this case, perpetually aching, ruined feet, which get several pointed close-ups, and are always present in the clomping, stiff walk that Goldberg adopts. But it still has that Mississppi Burning thing where it can't get away from wanting to talk about the effect this all had on white folk, in this case Miriam. Not for nothing that she gets the only actual dramatic arc in the movie: Odessa suffers, at length, but she doesn't really change because there's nothing for her to change to: she's in the right, the movie knows she's right, and that is that. Miriam is a much more interesting character, in part because the film seems to feel a bit guilty about itself, and so it uses her to indict a certain kind of paternalistic liberalism. Miriam, you see, is not a vicious racist: she is, by the standards of white society in Alabama in 1955, extremely progressive, so much so that it causes problems for her husband and makes people gossip behind her back. And Spacek makes sure that we see that Miriam knows this, and congratulates herself for it. The little twist, and this is where I suggest that the film at least somewhat tackles the genre head-on, is that Odessa finds Miriam to be only slightly less objectionable than the overt racists that make up most of the white cast, and so we are invited to do the same. The film's main message, then, turns out not to be about the boycotts at all, but about the limits of self-satisfied progressive attitudes; one recalls Martin Luther King, Jr's criticism that the white liberal is in some ways the most insidious of all enemies, since she believes that vocalising respect and love is the same as facilitating real material change.

This isn't by any means the most radical message for what is, after all, a Hollywood message movie, but it does give the film a bitter bite that most films about racism, with their One Good White Person, tend to lack. And it gives Spacek a lot that she can work with, on the way to getting an admittedly pretty comforting, pat conclusion that would tend to run contrary to a lot of what I just said. Still, there's no gainsaying the power of a good role for a good actor, and Spacek and Goldberg both do a hell of a lot in The Long Walk Home that's very easy to like - Goldberg, in particular, is maybe as good as I've seen her in anything outside of The Color Purple, playing the role small and letting Odessa's resentment trickle out through her eyes and her mouth, which at all points seems to have been carved out of stone, so judiciously does Goldberg reserve any significant movements in her face for when they'll count.

The fact remains, though, that the film is kind of cumbersomely split between giving Miriam a satisfying character arc and giving Odessa satisfying thematic arc, and these two parts of the film weirdly do not talk to each other much. I wouldn't say that a film with complex white characters can't have anything to say about racism, but a film about a complex white character and a Black character who exists more as a set of behaviors than an internal personality certainly isn't making things easy on itself. And we simply get a much better sense of who Miriam is than Odessa, all throughout the movie - even just considering how much fuller Miriam's family drama is than Odessa's (the only scene where here family makes much of an impression at all is when they give her a surprise Christmas present), that's true. There are enough strengths, stylistically and in the way it approaches its message, for The Long Walk Home to stand as a considerably above-average Oscarbait movie about racism; there are also enough strengths to make the whole movie feel a little bit more pedestrian for not being able to capitalise on them more.

Do you have a movie you'd like to see reviewed? This and other perks can be found on our Patreon page!

There aren't too many formulations that make me instantaneously suspicious of a movie more than A) a story about historical racism in the United States, B) with a release strategy that clearly indicates they were sniffing for some Academy Awards (in this case, New York and Los Angeles on 21 December 1990, delayed in the rest of the country until 22 March 1991), C) with more white people than African-Americans in the top-line cast, D) from the 1980s or early 1990s. That I still ended up finding some real value in The Long Walk Home is genuinely surprising to me: it's not a perfect movie by any stretch of the imagination, but it's honestly a lot more thoughtful about how it wants to tell a story of the Montgomery, AL bus boycott of 1955-'56 than I would have expected, and it tackles one of the biggest problems this kind of story is likely to face head-on. Or, if not quite head-on, in the end, at least from a fairly steep angle.

That problem being the annoying tendency for films about racism to actually be about white people who are sad about racism, or who learn to be sad about racism. In this case, that white person is Miriam Thompson (Sissy Spacek), a housewife with who lives comfortably with her two daughters, Mary Catherine (Lexi Randall) and Sara (Crystal Robbins), and a meek husband, Norman (Dwight Schultz, who got an above-the-title credit despite being best-known as the lead of The A-Team that you need to really stop and think about after you've already come up with Mr. T, George Peppard, and Dirk Benedict. That's how you know this is an indie movie). They are thoroughly unremarkable members of Montogomery's upper-middle-class, and like everyone else in that class, they have a Black maid, Odessa Cotter (Whoopi Goldberg), who has to take the bus to the Thompson house every day. And so it continues until 5 December, 1955, when Montgomery's African-American population boycotts the city's bus system in protest of the arrest of Rosa Parks a few days earlier. This is a major upheaval for the entire city for a multitude of reasons, but the one we care about the most is that Odessa now has a hell of a long way to walk to and from her job at the Thompsons' place, and it very quickly starts to wear her body down to go along with the deep misery of her heart.

A couple of things to pull out of there right away. First, if you noticed how that précis starts on Miriam and ends on Odessa, then you have grasped the structural clunkiness that The Long Walk Home hasn't figured out how to solve, or has figured out and doesn't want to solve. Related to that, if you noticed that I didn't list out Odessa's family members - she has a matched set to balance Miriam's, including Ving Rhames as her husband - then you have grasped one specific way that the clunky structure manifests itself.

As written by John Cork, for whom this is a very lightly autobiographical effort (as a child, he would have been analogous to Mary Catherine, who narrates the first and last scenes of the film as an adult, in the voice of Mary Steenburgen), The Long Walk Home is split pretty close to write down the middle between Miriam and Odessa. Spacek is top-billed; if I were forced to guess without having timed it, I think Goldberg probably has slightly more screentime. Either way, the film works hard to balance itself as the story of two women who experienced the Montgomery bus boycott from two very different directions. And I do mean hard: it never comes organically. And these two stories are not created equal: Odessa's experience, which involves slightly reluctant solidarity with her community that very quickly turns into real activist commitment, is self-evidently the more intellectually gratifying approach, since it understands the boycott as a purposeful, material thing, a matter of difficult choices and political strategies, and the expression of a community that we see portrayed over and over again in the film in huge group shots and very geometrically-precise church interiors. Richard Pearce is not a director who has much in the way of a notable career, but he's given some very clear thought to how to visually distinguish the two racial worlds in the film, and this invariably favors the African-American communities, who feel like they have been worked into a distinct visual strategy, rather than the white people who are just kind of lumped into by-the-books late-'80s prestige filmmaking. It doesn't hurt that Pearce has a ringer of a cinematographer in the form of Roger Deakins (whose very next film would be the career-making Barton Fink) who isn't doing anything particularly showy here, but who does remarkable, nuanced work in modulating the amount of diffuse sunshine to give different parts of Montgomery some very different visual characteristics, and always with a slightly darker, more realistic foundation that I am used to from this era of middlebrow message films.

So the film tends to stylistically favor Odessa (this is also true, by the way, of George Fenton's gooey, tackily sentimental score; I do not at all care for it, but it is interesting that it's really only activating itself in scenes about Black people). And because of this, it seems to understand that the story of the bus boycott really does need to be told via the people doing the boycott, with an eye on what it cost them - in this case, perpetually aching, ruined feet, which get several pointed close-ups, and are always present in the clomping, stiff walk that Goldberg adopts. But it still has that Mississppi Burning thing where it can't get away from wanting to talk about the effect this all had on white folk, in this case Miriam. Not for nothing that she gets the only actual dramatic arc in the movie: Odessa suffers, at length, but she doesn't really change because there's nothing for her to change to: she's in the right, the movie knows she's right, and that is that. Miriam is a much more interesting character, in part because the film seems to feel a bit guilty about itself, and so it uses her to indict a certain kind of paternalistic liberalism. Miriam, you see, is not a vicious racist: she is, by the standards of white society in Alabama in 1955, extremely progressive, so much so that it causes problems for her husband and makes people gossip behind her back. And Spacek makes sure that we see that Miriam knows this, and congratulates herself for it. The little twist, and this is where I suggest that the film at least somewhat tackles the genre head-on, is that Odessa finds Miriam to be only slightly less objectionable than the overt racists that make up most of the white cast, and so we are invited to do the same. The film's main message, then, turns out not to be about the boycotts at all, but about the limits of self-satisfied progressive attitudes; one recalls Martin Luther King, Jr's criticism that the white liberal is in some ways the most insidious of all enemies, since she believes that vocalising respect and love is the same as facilitating real material change.

This isn't by any means the most radical message for what is, after all, a Hollywood message movie, but it does give the film a bitter bite that most films about racism, with their One Good White Person, tend to lack. And it gives Spacek a lot that she can work with, on the way to getting an admittedly pretty comforting, pat conclusion that would tend to run contrary to a lot of what I just said. Still, there's no gainsaying the power of a good role for a good actor, and Spacek and Goldberg both do a hell of a lot in The Long Walk Home that's very easy to like - Goldberg, in particular, is maybe as good as I've seen her in anything outside of The Color Purple, playing the role small and letting Odessa's resentment trickle out through her eyes and her mouth, which at all points seems to have been carved out of stone, so judiciously does Goldberg reserve any significant movements in her face for when they'll count.

The fact remains, though, that the film is kind of cumbersomely split between giving Miriam a satisfying character arc and giving Odessa satisfying thematic arc, and these two parts of the film weirdly do not talk to each other much. I wouldn't say that a film with complex white characters can't have anything to say about racism, but a film about a complex white character and a Black character who exists more as a set of behaviors than an internal personality certainly isn't making things easy on itself. And we simply get a much better sense of who Miriam is than Odessa, all throughout the movie - even just considering how much fuller Miriam's family drama is than Odessa's (the only scene where here family makes much of an impression at all is when they give her a surprise Christmas present), that's true. There are enough strengths, stylistically and in the way it approaches its message, for The Long Walk Home to stand as a considerably above-average Oscarbait movie about racism; there are also enough strengths to make the whole movie feel a little bit more pedestrian for not being able to capitalise on them more.