You know how to whistle, don't you?

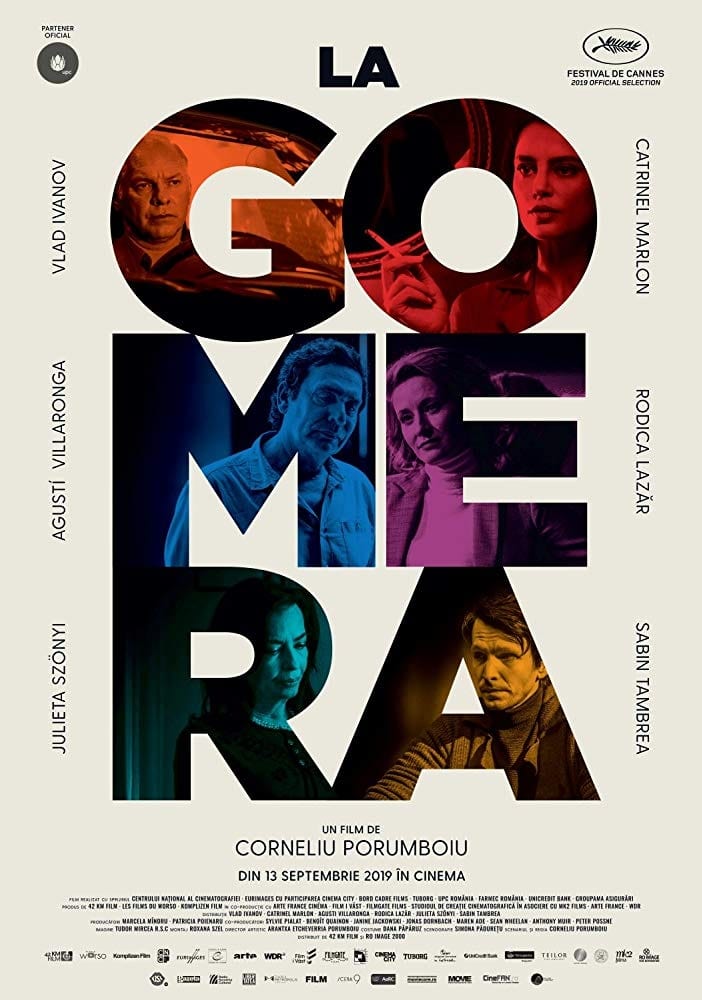

For as long as the Romanian New Wave of the mid-2000s could be identified as such, Corneliu Porumboiu has been, I think, the director to make the easiest, most likable films. This is mostly because he's the only one of the major, exportable Romanian filmmakers to focus on comedies, however biting and bleak their satiric intent might be. And now we come to his fifth feature, The Whistlers, which might very well be his easiest, most likable film yet, though at a cost: it's also probably his film that feels the most trivial in its concerns. Whereas the director's best work, which I consider to still be his first two features, 12:08 East of Bucharest from 2006 and Police, Adjective from 2009 - actually, pretty much all of his work, till now - has some manner of nibbling satiric, political bite to it, The Whistlers feels to me like very little other than a genre riff for the sake of doing a genre riff. But it is a good genre riff, so it has that going for it.

That genre is the crime thriller, particularly the kind of film noir about a hopeless dope who's gotten suckered into something hoping to impress a sexy woman. It even has the in media res opening that then nests in some flashbacks, that was more or less invented in film noir before becoming omnipresent; the structure feels more purposeful here than it has in a while, maybe because Porumboiu doesn't just present one smooth flashback, he jumbles up the entire narrative into eight large chunks which are shown just enough out of order that you're obliged to pay attention and keep on your toes, but not so much that you can't actually follow what's happening just at the level of mood and rhythm.

Our dope for the evening is Cristi (Vlad Ivanov), who starts the film off by arriving at La Gomera, one of the Canary Islands, as Iggy Pop's "The Passenger" plays on the soundtrack, lashing a sarcastic meaning onto the pointedly flat images. And then, once we see him poking about a bit stupidly, we find out why he's on La Gomera (the island's name is the film's title in its native Romania, incidentally): he's a crooked cop in bed with Bucharest money launderer Zsolt (Sabin Tambrea), who has some Spanish business contacts that need to be handled. The other Bucharest cops - I will not the "good" cops, but the cops whose corrpution hasn't put them in Zsolt's sphere of influence - are starting to sniff around Cristi more than he's comfortable with, so his current mode of communicating is to visit Zsolt's girlfriend Gilda (Catrinel Marlon), in the guise that he's sleeping with her. Given that he has a massive crush on her, this suits Cristi just fine. What this has to do with La Gomera is that Zsolt wants him to learn Silbo Gomero, an ancient language of whistling developed by the inhabitants of that island as a means of long-distance communication. Or, if you're a bent cop in a crime picture, a means of communicating secrets right out in the open in Bucharest through a language that doesn't register as a language, if you don't know what you're hearing.

This is a hell of a lot of plot for a Romanian art film, and Porumboiu is not, apparently, asking us to take it very seriously at all. The complicated structure of The Whistlers is a pretty clear indication, in context, that it's all so much convoluted nonsense designed mostly to put Cristi in way over his head, and to give Ivanov a good opportunity to flex his jowly, hangdog face and look suitably pathetic and miserable. From the moment "The Passenger" starts playing, the film is much more openly interested in creating a mood than in telling a story, and indeed one of things that The Whistlers demonstrates is that Porumboiu has a good sense of what piece of music will match best with the stilted, deadpan vibe he's trying to create in any given scene, all of which sets up the film's extremely weird and unexpected final scene, a little bit of almost entirely plotless "I found this strange and amazing place that I want you to see" pure cinema that reminds me of the kind of shaggy go-nowhere material that so entrances e.g. Werner Herzog.

In a sense, the whole movie is that exact kind of shaggy thing. The shenanigans that Cristi gets involved in, and the many people on multiple sides trying to mess with him, are routine enough noir stereotypes that it's hard to care very much where things go; it's all about the little moments and offbeats idea that film stumbles upon as it goes. The most obvious of these is Silbo Gomero itself: the whistling language gets simultaneously less screentime than it deserves if it's going to the primary metaphor within the film, and far more than it ever justifies in terms of its plot importance. And this, I should think, largely because Porumboiu learned about the language and immediately grew fascinated with it. As, I think, any one of us surely would have. It falls right into his career-long interest in how we use communication as a way of struggling over power and controlling information rather than just imparting facts to each other (there are unmistakable echoes of Police, Adjective, which also starred Ivanov, and its epic disagreements about grammar), but mainly, it's here because it gives a distinct aura of the unmentionably absurd to see rugged, beefy, gangster-looking men tensely whistle at each other and have the whistles get their own subtitles.

This is a comedy after all, however extraordinarily deadpan (for example: the film's first big joke involves very conspicuous sound editing in the middle of a music cue; later, one joke's punchline is that the film doesn't parody an extremely famous moment in the history of genre cinema, and the character involved in the non-parody seems confused and disappointed by this). The humor, like the narrative, is mostly about atmosphere: do we find the whole thing all quite ludicrous, and Cristi much too grubby and sad and hapless to be even a film noir protagonist? Then we probably see why the response the film asks for is that we laugh, rather than find it tense and exciting. This degree to which The Whistlers invests in the low-rent shabbiness of its cloak-and-dagger mechanics does make it feel a bit glib, maybe; it definitely feels more like a collection of well-made scenes, rather than a strong, cohesive movie, and not just because of how blatantly it divides itself into chapters. Granting all of that, they are well-made scenes, and Ivanov is a great pathetic sad sack, and watching the gloomy, fatalistic matter of film noir play out in banal, naturalistic scenes shot on the streets of Bucharest and the dramatic crags of La Gomera, and in the languid style of Romanian art cinema, is pretty amusing, in its bone-dry deadpan way. This is surely Porumboiu's most laid-back, purely playful feature to date, even as it feels like it probably took the most effort to make it and keep all of its moving parts in order, so it's also somehow his most ambitious; that paradox of taking a great deal of effort to do or say basically nothing is kind of just another one of the film's gags, and not by any means its least effective one.

That genre is the crime thriller, particularly the kind of film noir about a hopeless dope who's gotten suckered into something hoping to impress a sexy woman. It even has the in media res opening that then nests in some flashbacks, that was more or less invented in film noir before becoming omnipresent; the structure feels more purposeful here than it has in a while, maybe because Porumboiu doesn't just present one smooth flashback, he jumbles up the entire narrative into eight large chunks which are shown just enough out of order that you're obliged to pay attention and keep on your toes, but not so much that you can't actually follow what's happening just at the level of mood and rhythm.

Our dope for the evening is Cristi (Vlad Ivanov), who starts the film off by arriving at La Gomera, one of the Canary Islands, as Iggy Pop's "The Passenger" plays on the soundtrack, lashing a sarcastic meaning onto the pointedly flat images. And then, once we see him poking about a bit stupidly, we find out why he's on La Gomera (the island's name is the film's title in its native Romania, incidentally): he's a crooked cop in bed with Bucharest money launderer Zsolt (Sabin Tambrea), who has some Spanish business contacts that need to be handled. The other Bucharest cops - I will not the "good" cops, but the cops whose corrpution hasn't put them in Zsolt's sphere of influence - are starting to sniff around Cristi more than he's comfortable with, so his current mode of communicating is to visit Zsolt's girlfriend Gilda (Catrinel Marlon), in the guise that he's sleeping with her. Given that he has a massive crush on her, this suits Cristi just fine. What this has to do with La Gomera is that Zsolt wants him to learn Silbo Gomero, an ancient language of whistling developed by the inhabitants of that island as a means of long-distance communication. Or, if you're a bent cop in a crime picture, a means of communicating secrets right out in the open in Bucharest through a language that doesn't register as a language, if you don't know what you're hearing.

This is a hell of a lot of plot for a Romanian art film, and Porumboiu is not, apparently, asking us to take it very seriously at all. The complicated structure of The Whistlers is a pretty clear indication, in context, that it's all so much convoluted nonsense designed mostly to put Cristi in way over his head, and to give Ivanov a good opportunity to flex his jowly, hangdog face and look suitably pathetic and miserable. From the moment "The Passenger" starts playing, the film is much more openly interested in creating a mood than in telling a story, and indeed one of things that The Whistlers demonstrates is that Porumboiu has a good sense of what piece of music will match best with the stilted, deadpan vibe he's trying to create in any given scene, all of which sets up the film's extremely weird and unexpected final scene, a little bit of almost entirely plotless "I found this strange and amazing place that I want you to see" pure cinema that reminds me of the kind of shaggy go-nowhere material that so entrances e.g. Werner Herzog.

In a sense, the whole movie is that exact kind of shaggy thing. The shenanigans that Cristi gets involved in, and the many people on multiple sides trying to mess with him, are routine enough noir stereotypes that it's hard to care very much where things go; it's all about the little moments and offbeats idea that film stumbles upon as it goes. The most obvious of these is Silbo Gomero itself: the whistling language gets simultaneously less screentime than it deserves if it's going to the primary metaphor within the film, and far more than it ever justifies in terms of its plot importance. And this, I should think, largely because Porumboiu learned about the language and immediately grew fascinated with it. As, I think, any one of us surely would have. It falls right into his career-long interest in how we use communication as a way of struggling over power and controlling information rather than just imparting facts to each other (there are unmistakable echoes of Police, Adjective, which also starred Ivanov, and its epic disagreements about grammar), but mainly, it's here because it gives a distinct aura of the unmentionably absurd to see rugged, beefy, gangster-looking men tensely whistle at each other and have the whistles get their own subtitles.

This is a comedy after all, however extraordinarily deadpan (for example: the film's first big joke involves very conspicuous sound editing in the middle of a music cue; later, one joke's punchline is that the film doesn't parody an extremely famous moment in the history of genre cinema, and the character involved in the non-parody seems confused and disappointed by this). The humor, like the narrative, is mostly about atmosphere: do we find the whole thing all quite ludicrous, and Cristi much too grubby and sad and hapless to be even a film noir protagonist? Then we probably see why the response the film asks for is that we laugh, rather than find it tense and exciting. This degree to which The Whistlers invests in the low-rent shabbiness of its cloak-and-dagger mechanics does make it feel a bit glib, maybe; it definitely feels more like a collection of well-made scenes, rather than a strong, cohesive movie, and not just because of how blatantly it divides itself into chapters. Granting all of that, they are well-made scenes, and Ivanov is a great pathetic sad sack, and watching the gloomy, fatalistic matter of film noir play out in banal, naturalistic scenes shot on the streets of Bucharest and the dramatic crags of La Gomera, and in the languid style of Romanian art cinema, is pretty amusing, in its bone-dry deadpan way. This is surely Porumboiu's most laid-back, purely playful feature to date, even as it feels like it probably took the most effort to make it and keep all of its moving parts in order, so it's also somehow his most ambitious; that paradox of taking a great deal of effort to do or say basically nothing is kind of just another one of the film's gags, and not by any means its least effective one.