Christian behavior

It will always be a little asterisk on the career of director Ingmar Bergman that the film for which he always has been and likely always will be best-known, 1957's The Seventh Seal, is among the least-characteristic films he ever made. This is, in and of itself, neither good nor bad, nor anything (though it does guarantee that generations of cinephiles will continue to have the whiplash of going from that to whatever film they select for their second Bergman picture*). It just means that a filmmaker concerned to the point of mania with Strindbergian chamber dramas about domestic relationships will somehow always be associated with symbolic religious allegory, a mode he worked in a grand total of twice.

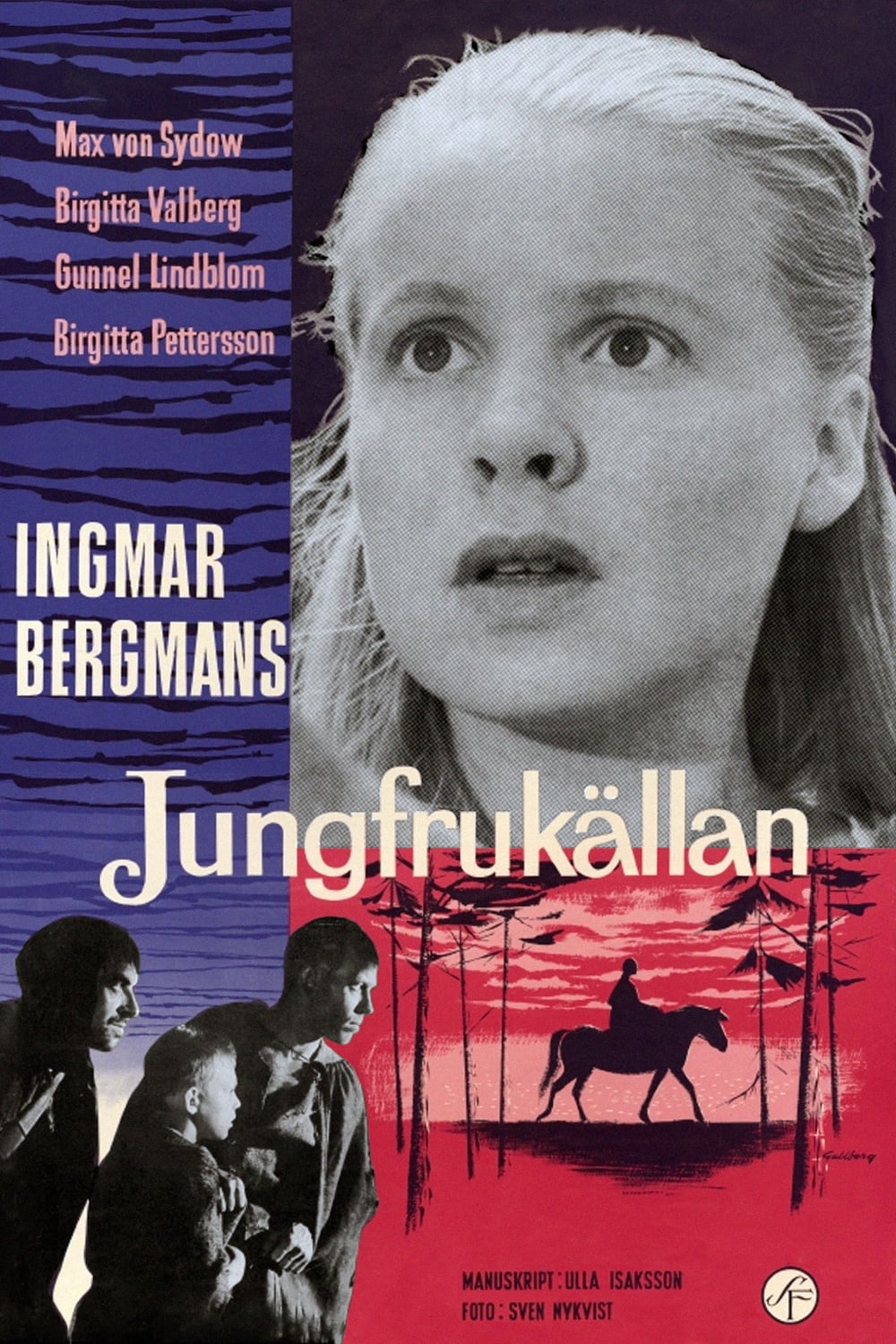

We're here to talk about the second time, 1960's The Virgin Spring, which arguably represents the peak of the first wave of Bergmania. Having erupted onto the international stage three years earlier, Bergman received with this film the status of celebrated auteur: it was his final film to play in competition at Cannes, where he won a special commendation, and it won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film, as sure a sign of middlebrow acceptance and penetration as one could hope to get. And this global recognition arrived, perhaps inevitably, on the back of film that I might uncharitably, but I think accurately, refer to as "The Seventh Seal, Part II".

Once again, we're in medieval Sweden, and once again, hushed religious allegory is the name of the game. The film tips its hand almost instantly, starting with a pair of short scenes held in obvious balance with each other: first, a young woman named Ingeri (Gunnel Lindblom), in mottled grey lighting, offers up her prayers to Odin; second, shot with much plusher shadows and contrast, a man named Töre (Max von Sydow) offers his own prayers, to the the Christian God. Everything about these two scenes plays off each other: the explicit content, of course, but also the angles, and the way the characters are brought into the scene - Ingeri immediately registers as more present and embodied than Töre, who has a hushed, offscreen presence. It's an opening that very loudly announces that we're here for a story that will, at least in part, concern itself with the tension between paganism and Christianity in a moment of great change throughout northern Europe.

As it turns out, that particular thread turns out to be only a portion of what The Virgin Spring wants to look at, though symbolism is absolutely going to be one of its main strategies. Bergman had been interested in adapting a traditional ballad about Töre and his legendary building of the 12th Century church in Kärna, and he commissioned his friend, the author Ulla Isaksson, to write a screenplay on the topic; this was their second and final collaboration, after 1958's Brink of Life. What Isaksson produced is, by all means, the work of a literary author: full of densely packed images and elaborate flourishes of moral philosophy designed to be mulled over a bit more than to be performed by actors, maybe. But even if it's a bit stiff in the execution, there's plenty to be said for a movie that thinks as long and hard about what is and is not morally corrupting as this one does. The scenario used to tease out this morality is simple as an aphorism (and I am going to spoil the end of the movie, because you've kind of got to): Töre's daughter Karin (Birgitta Pettersson) is tasked with taking a delivery of candles to the church on the far side of the forest, accompanied by the Ingeri, the family's servant. Along the way, the women cross paths with two herdsmen (Axel Düberg, Tor Isedal) and their younger brother (Ove Porath), who rape and murder Karin while Ingeri, having been separated from the other woman, hides in trees watching. Shortly thereafter, the herdsmen seek shelter at the home of Töre and his wife (Birgitta Valberg); by the end of the night, they have realised what crime their new houseguests committed, and Töre has perpetrated an act of grisly retribution. This having been done, he throws himself on God's mercy, begging forgiveness for his wilful embrace of violent revenge.

The story as it plays out is quite a bit different than this probably makes it sound; by the time the first of the above plot points even shows up, we're comfortably halfway through the 90-minute feature. And this is because Bergman and Isaksson aren't really interested in the crime or retribution per se as they are in the creation of an entire moral universe. The slow unfurling of the four main characters' lives, and particularly the unforced juxtaposition of the pagan Ingeri and the Christian Töre, is placed in front of us without any urgency at all, and the film has a way of wrapping its world around us gently as we sit there marianating in it. It's almost like a very strange version of naturalism, except that no aspect of the writing, acting, or cinematography is even slightly naturalistic. But it has the rhythm of that kind of documentary immersion.

This is one of the biggest ways that The Virgin Spring ends up feeling like a heavy blanket of ashen-faced moral doubt: the film's world seems to be motivated less by its own existence than by an omnipresent feeling of pensive confusion and dread, spiked by frequent appeals to unseen, unheard deities. It is, I would readily say, the first of Bergman's films that fully lives up to his reputation for being crushingly depressing; even setting aside the shocking directness of the rape scene, the whole film is hushed and solemn. If there is a single piece of non-diegetic music outside of the simple tune playing over the opening credits, I missed it. The acting is full of silent, internal conflict, with von Sydow and Lindblom especially doing exemplary work in embodying how their characters feel the punishing cruelty of the word but lack the sensibility, or perhaps just the bravery, to articulate that. Lindblom is particularly great; she's not typically spoken of in the same exalted tones as the other actresses Bergman worked with this often (eight times!), which I suppose is because she almost always played supporting roles. She is, indeed, playing a supporting role in The Virgin Spring. But she's playing it so perfectly that she tends to dominate my memories of the film, presenting a figure turned so intensely inwards that it feels like every word she says has to be barked out from behind her panicky, wild eyes and through her distressingly tense body language. In a film all about the horrifying uncertainty of the world, she is the figure through whom we see the clearest reactions to that horror: seething rage, paralysing terror, desperate hope.

The other thing that really sells the weight of the film is the cinematography: this was Bergman's second collaboration with Sven Nykvist (who worked on parts of Sawdust and Tinsel), but it's sort of the first one to "count"; virtually every one of the director's films from this point until he was functionally retired in the 1980s was shot by Nykvist, and this would, in due course, become quite possibly the great director/cinematographer collaboration in all of cinema. We get a healthy preview of things to come already in The Virgin Spring, which deftly contrasts the dark interior spaces of the family's home with the straining brightness of the forest. The latter is perfectly beautiful in its own right, relying on the whiter side of the full greyscale to create a vividly textured realm of layers and surfaces, with camera angles always emphasising the crowded closeness of trees whose light bark feels both clean and dessicated. It is quite obvious, even before Bergman confirms it for us, that he was thinking very specifically about Kurosawa Akira's Rashomon, and the way that film uses warm sunshine in a forest glade to make a scene of rape and murder feel paradoxically more oppressive and menacing. But it's the interiors where Nykvist is really looking to knock our socks off. The movie feels like it has been carved out of pure shadow to surround and frame the characters, Töre especially, in pools of negative space; there is a shot as he steels himself against his decision and its consequences, that simply puts von Sydow in a chair facing directly towards the camera, framed in the center of the shot, and the looming weight of the murky top third of the composition blankets the rigid geometry in the busier bottom half.

In short: a heavy movie about horrible things, with all of its style and aesthetics lined up to accentuate this heaviness. I would perhaps at this point grouse that it's too heavy, but honestly, I think The Virgin Spring is far and away at its best when it leans into these emphatic, bold-faced moments of grandiose thematics and intensified human misery. Its finest moments are its most self-consciously mythic, when the archness of the performances and the painterly gloom are allowed to attack Big Questions About God And Morality.

It gets a great deal lumpier when it tries to ratchet its focus back to its actual characters and dramatic spine. It's not really possible, based on the evidence of this and Brink of Life, whether Isaksson wasn't a natural-born screenwriter (as many literary writers throughout history have not been), or if it's simply that Bergman had a hard time finding his way onto her wavelength. It could be both things, presumably, but whatever the case, there's something missing here. Especially compared to The Seventh Seal, a comparison it's almost impossible to avoid making, The Virgin Spring simply feels lesser. The characters are less rich in their personality; the sense of the cosmic is smaller. The story feels more schematic, and the ideas more cautious, though this latter point is perhaps affected by how nervous the ending feels relative to the rest: after having spent an entire film probing into Töre's behavior, finding in him a sad and terrified example of someone who uses blind faith in an unspeaking God to hide from the bleak truth of the world, while pitying him for subscribing to a moral code that demands he constantly punish himself, the film swerves in the last scene into "ah, well, the Lord works in mysterious ways". It's an immaculately-staged, beautifully-shot final scene, but it's too neat, no matter how grim and death-soaked it is.

It's also one of the few times that I really do wonder if it needed to be quite so blackhearted. Bergman's films are full of suffering and cruelty, we all know this, but by and large, that suffering is small and domestic, a matter of psychology, and this is the mode the director thrives in. The Virgin Spring is bigger than that, and especially in its deeply uncomfortable rape scene, I think it goes too far into pure misery for misery's sake, and only the way that it's being channeled through Ingeri's POV helps to make it at least somewhat productive for the character drama.

All of which is to say: I couldn't and wouldn't gainsay the sheer force of The Virgin Spring, but of all the films upon which Bergman's international reputation was made during he peak of his career in the 1960s, this is probably the one I care for the least. It's a strong piece by a strong team of craftspeople and actors, but it's not playing to the director's strengths, and its core questoin - how do we function in the face of God's silence? - is one that he'd ask with much more elegance and resonance multiple times in the years to come.

Still, there's no disputing its influence. This is the film, after all, that moved young Andrei Tarkovsky so deeply that he declared Bergman to be one of the only real artists working in cinema in the '60s, and his own career was bookended by references to the film: obliquely, in the case of the birch forest of 1962's Ivan's Childhood, and very, very directly in the tree-raising scene of 1986's The Sacrifice. And then all the way on the far end of pretty much every single spectrum I can think of, Wes Craven made his directorial debut with an uncredited but very direct remake in the form of the extremely violent exploitation film The Last House on the Left, from 1972. And I am quite sure I can't name two films with a shared influence less comparable than Last House and The Sacrifice - that it was able to inspire two such vastly dissimilar projects is, in its way, the finest testament I can offer to how prodigious The Virgin Spring really is.

*For me, back in 2001, it was Cries and Whispers.

We're here to talk about the second time, 1960's The Virgin Spring, which arguably represents the peak of the first wave of Bergmania. Having erupted onto the international stage three years earlier, Bergman received with this film the status of celebrated auteur: it was his final film to play in competition at Cannes, where he won a special commendation, and it won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film, as sure a sign of middlebrow acceptance and penetration as one could hope to get. And this global recognition arrived, perhaps inevitably, on the back of film that I might uncharitably, but I think accurately, refer to as "The Seventh Seal, Part II".

Once again, we're in medieval Sweden, and once again, hushed religious allegory is the name of the game. The film tips its hand almost instantly, starting with a pair of short scenes held in obvious balance with each other: first, a young woman named Ingeri (Gunnel Lindblom), in mottled grey lighting, offers up her prayers to Odin; second, shot with much plusher shadows and contrast, a man named Töre (Max von Sydow) offers his own prayers, to the the Christian God. Everything about these two scenes plays off each other: the explicit content, of course, but also the angles, and the way the characters are brought into the scene - Ingeri immediately registers as more present and embodied than Töre, who has a hushed, offscreen presence. It's an opening that very loudly announces that we're here for a story that will, at least in part, concern itself with the tension between paganism and Christianity in a moment of great change throughout northern Europe.

As it turns out, that particular thread turns out to be only a portion of what The Virgin Spring wants to look at, though symbolism is absolutely going to be one of its main strategies. Bergman had been interested in adapting a traditional ballad about Töre and his legendary building of the 12th Century church in Kärna, and he commissioned his friend, the author Ulla Isaksson, to write a screenplay on the topic; this was their second and final collaboration, after 1958's Brink of Life. What Isaksson produced is, by all means, the work of a literary author: full of densely packed images and elaborate flourishes of moral philosophy designed to be mulled over a bit more than to be performed by actors, maybe. But even if it's a bit stiff in the execution, there's plenty to be said for a movie that thinks as long and hard about what is and is not morally corrupting as this one does. The scenario used to tease out this morality is simple as an aphorism (and I am going to spoil the end of the movie, because you've kind of got to): Töre's daughter Karin (Birgitta Pettersson) is tasked with taking a delivery of candles to the church on the far side of the forest, accompanied by the Ingeri, the family's servant. Along the way, the women cross paths with two herdsmen (Axel Düberg, Tor Isedal) and their younger brother (Ove Porath), who rape and murder Karin while Ingeri, having been separated from the other woman, hides in trees watching. Shortly thereafter, the herdsmen seek shelter at the home of Töre and his wife (Birgitta Valberg); by the end of the night, they have realised what crime their new houseguests committed, and Töre has perpetrated an act of grisly retribution. This having been done, he throws himself on God's mercy, begging forgiveness for his wilful embrace of violent revenge.

The story as it plays out is quite a bit different than this probably makes it sound; by the time the first of the above plot points even shows up, we're comfortably halfway through the 90-minute feature. And this is because Bergman and Isaksson aren't really interested in the crime or retribution per se as they are in the creation of an entire moral universe. The slow unfurling of the four main characters' lives, and particularly the unforced juxtaposition of the pagan Ingeri and the Christian Töre, is placed in front of us without any urgency at all, and the film has a way of wrapping its world around us gently as we sit there marianating in it. It's almost like a very strange version of naturalism, except that no aspect of the writing, acting, or cinematography is even slightly naturalistic. But it has the rhythm of that kind of documentary immersion.

This is one of the biggest ways that The Virgin Spring ends up feeling like a heavy blanket of ashen-faced moral doubt: the film's world seems to be motivated less by its own existence than by an omnipresent feeling of pensive confusion and dread, spiked by frequent appeals to unseen, unheard deities. It is, I would readily say, the first of Bergman's films that fully lives up to his reputation for being crushingly depressing; even setting aside the shocking directness of the rape scene, the whole film is hushed and solemn. If there is a single piece of non-diegetic music outside of the simple tune playing over the opening credits, I missed it. The acting is full of silent, internal conflict, with von Sydow and Lindblom especially doing exemplary work in embodying how their characters feel the punishing cruelty of the word but lack the sensibility, or perhaps just the bravery, to articulate that. Lindblom is particularly great; she's not typically spoken of in the same exalted tones as the other actresses Bergman worked with this often (eight times!), which I suppose is because she almost always played supporting roles. She is, indeed, playing a supporting role in The Virgin Spring. But she's playing it so perfectly that she tends to dominate my memories of the film, presenting a figure turned so intensely inwards that it feels like every word she says has to be barked out from behind her panicky, wild eyes and through her distressingly tense body language. In a film all about the horrifying uncertainty of the world, she is the figure through whom we see the clearest reactions to that horror: seething rage, paralysing terror, desperate hope.

The other thing that really sells the weight of the film is the cinematography: this was Bergman's second collaboration with Sven Nykvist (who worked on parts of Sawdust and Tinsel), but it's sort of the first one to "count"; virtually every one of the director's films from this point until he was functionally retired in the 1980s was shot by Nykvist, and this would, in due course, become quite possibly the great director/cinematographer collaboration in all of cinema. We get a healthy preview of things to come already in The Virgin Spring, which deftly contrasts the dark interior spaces of the family's home with the straining brightness of the forest. The latter is perfectly beautiful in its own right, relying on the whiter side of the full greyscale to create a vividly textured realm of layers and surfaces, with camera angles always emphasising the crowded closeness of trees whose light bark feels both clean and dessicated. It is quite obvious, even before Bergman confirms it for us, that he was thinking very specifically about Kurosawa Akira's Rashomon, and the way that film uses warm sunshine in a forest glade to make a scene of rape and murder feel paradoxically more oppressive and menacing. But it's the interiors where Nykvist is really looking to knock our socks off. The movie feels like it has been carved out of pure shadow to surround and frame the characters, Töre especially, in pools of negative space; there is a shot as he steels himself against his decision and its consequences, that simply puts von Sydow in a chair facing directly towards the camera, framed in the center of the shot, and the looming weight of the murky top third of the composition blankets the rigid geometry in the busier bottom half.

In short: a heavy movie about horrible things, with all of its style and aesthetics lined up to accentuate this heaviness. I would perhaps at this point grouse that it's too heavy, but honestly, I think The Virgin Spring is far and away at its best when it leans into these emphatic, bold-faced moments of grandiose thematics and intensified human misery. Its finest moments are its most self-consciously mythic, when the archness of the performances and the painterly gloom are allowed to attack Big Questions About God And Morality.

It gets a great deal lumpier when it tries to ratchet its focus back to its actual characters and dramatic spine. It's not really possible, based on the evidence of this and Brink of Life, whether Isaksson wasn't a natural-born screenwriter (as many literary writers throughout history have not been), or if it's simply that Bergman had a hard time finding his way onto her wavelength. It could be both things, presumably, but whatever the case, there's something missing here. Especially compared to The Seventh Seal, a comparison it's almost impossible to avoid making, The Virgin Spring simply feels lesser. The characters are less rich in their personality; the sense of the cosmic is smaller. The story feels more schematic, and the ideas more cautious, though this latter point is perhaps affected by how nervous the ending feels relative to the rest: after having spent an entire film probing into Töre's behavior, finding in him a sad and terrified example of someone who uses blind faith in an unspeaking God to hide from the bleak truth of the world, while pitying him for subscribing to a moral code that demands he constantly punish himself, the film swerves in the last scene into "ah, well, the Lord works in mysterious ways". It's an immaculately-staged, beautifully-shot final scene, but it's too neat, no matter how grim and death-soaked it is.

It's also one of the few times that I really do wonder if it needed to be quite so blackhearted. Bergman's films are full of suffering and cruelty, we all know this, but by and large, that suffering is small and domestic, a matter of psychology, and this is the mode the director thrives in. The Virgin Spring is bigger than that, and especially in its deeply uncomfortable rape scene, I think it goes too far into pure misery for misery's sake, and only the way that it's being channeled through Ingeri's POV helps to make it at least somewhat productive for the character drama.

All of which is to say: I couldn't and wouldn't gainsay the sheer force of The Virgin Spring, but of all the films upon which Bergman's international reputation was made during he peak of his career in the 1960s, this is probably the one I care for the least. It's a strong piece by a strong team of craftspeople and actors, but it's not playing to the director's strengths, and its core questoin - how do we function in the face of God's silence? - is one that he'd ask with much more elegance and resonance multiple times in the years to come.

Still, there's no disputing its influence. This is the film, after all, that moved young Andrei Tarkovsky so deeply that he declared Bergman to be one of the only real artists working in cinema in the '60s, and his own career was bookended by references to the film: obliquely, in the case of the birch forest of 1962's Ivan's Childhood, and very, very directly in the tree-raising scene of 1986's The Sacrifice. And then all the way on the far end of pretty much every single spectrum I can think of, Wes Craven made his directorial debut with an uncredited but very direct remake in the form of the extremely violent exploitation film The Last House on the Left, from 1972. And I am quite sure I can't name two films with a shared influence less comparable than Last House and The Sacrifice - that it was able to inspire two such vastly dissimilar projects is, in its way, the finest testament I can offer to how prodigious The Virgin Spring really is.

*For me, back in 2001, it was Cries and Whispers.