Some say the world will end in fire

In all the annals of final films by great filmmakers, they don't come much more final than The Sacrifice, the seventh and last feature made by Andrei Tarkovsky. The director was diagnosed with the lung cancer that would ultimately kill him shortly after the film completed principal photography, and when it premiered at the 1986 Cannes International Film Festival, he was wasting away in Paris, too sick to travel; the film itself is a fable about the end of the world and the capacity of the individual human to cope with the very concept of "the end of the world" as a concrete, immediate thing. The initial concept for the story precedes its production by several years, certainly long enough that we should do well to avoid the simple, appealing story that Tarkovsky knew that this would be his final statement and designed it as such, but there's still something brutally emphatic about the film, and how much it seems to function as an apocalyptic summing-up of Tarkovsky's prodigious cosmology. And do mean apocalyptic not just in the sense of "the collapse of the world", but also in its literal meaning, a revelation of extraordinary wisdom.

I begin this way in part because I think it's impossible not to have these kinds of thoughts running through your head while watching the film, but also to safeguard myself against my own doubts. The Sacrifice is an extraordinary and rich film with profound depths; it's also a frustrating film that seems distressingly blind to its own deficiencies, and finds the writer-director fighting to express himself in a borrowed idiom that he obviously admires without having completely taken it into himself. And that's to say nothing of its incredible scenario, with a second half that pivots on an event at once too outlandish to register as anything but the stuff of metaphor and parable, and too trite and self-regarding to take entirely seriously.

Now that I've started the review down two different and perhaps even mutually exclusive paths, let me start to try and tie them together. Aye, I have doubts about The Sacrifice - great doubts even. But they are doubts that are much, much easier to have about a film that demands comparison to what very well might be the strongest body of work in cinema history, Tarkovsky's five unmitigated masterpieces stretching from Andrei Rublev in 1966 to Nostalghia in 1983. Just because the director kept living up to the standard he set for himself doesn't mean that it's fair to demand he do so; the miracle is that he produced five films in a row at that level of achievement.

Anyway, I claimed that the film uses a borrowed idiom, something that I don't think anybody could possibly dispute; it is, like, really obvious that this Tarkovsky's version of an Ingmar Bergman film. And there's certainly nothing wrong with that, as such. Bergman himself openly acknowledged Tarkovsky's films as a major influence on his own thoughts (Ivan's Childhood specifically), and it's kind of fun to think of all one's favorite austere European filmmakers liked each other's work and stole the best ideas from each other. In the case of The Sacrifice (which is in Swedish, kick-starting the similarities), we have the theft of one of Bergman's favorite leading men, Erland Josephson (who had a medium-sized but hugely important role in Nostalghia), and Bergman's longstanding cinematographer, Sven Nykvist. Just as crucially, if less famously, the film's production design was by Anna Asp, who'd joined the Bergman family late, with 1978's Autumn Sonata, and who received a rather bold Oscar win for Fanny and Alexander. And the film plays, especially for an enormously long stretch in the middle, very much like the theatrical chamber dramas that were Bergman's great love, the particularly Scandinavian masterpieces typified by the work of Ibsen and Strindberg.

The last of these points explains why Asp was such an important contributor to the film. The Sacrifice takes place in the isolated home of a well-off family, with a handful of very long scenes on the land around it, and a short sequence in a different building. Mostly, though, we're in that home, and for all that I would never dream of short-changing Nykvist's contribution - which is unmistakably his, in the best way possible - I really do feel like the film's visual aesthetic relies most of all on Asp's sets. The house feels impossibly big from the inside compared to what we see of the outside, with large gaping rooms that seem to go forever into the back and sides, while crushing down from the top. It's also extremely austere in a handsome, well-appointed way, all bone-white walls and rich dark brown woodwork and very little in the way of furniture. It feels unabashedly like a stage, and a bare one at that, and Tarkovsky moves his characters around that space in heavily determined blocking that makes them feel like they are trapped in a pageant-like trance, not of their choosing. It is airy and claustrophobic at the same time, the latter impression helped out by Nykvist's gloomy, wintry lighting, which feels like pale blocks running hard into murky shadows on the edges.

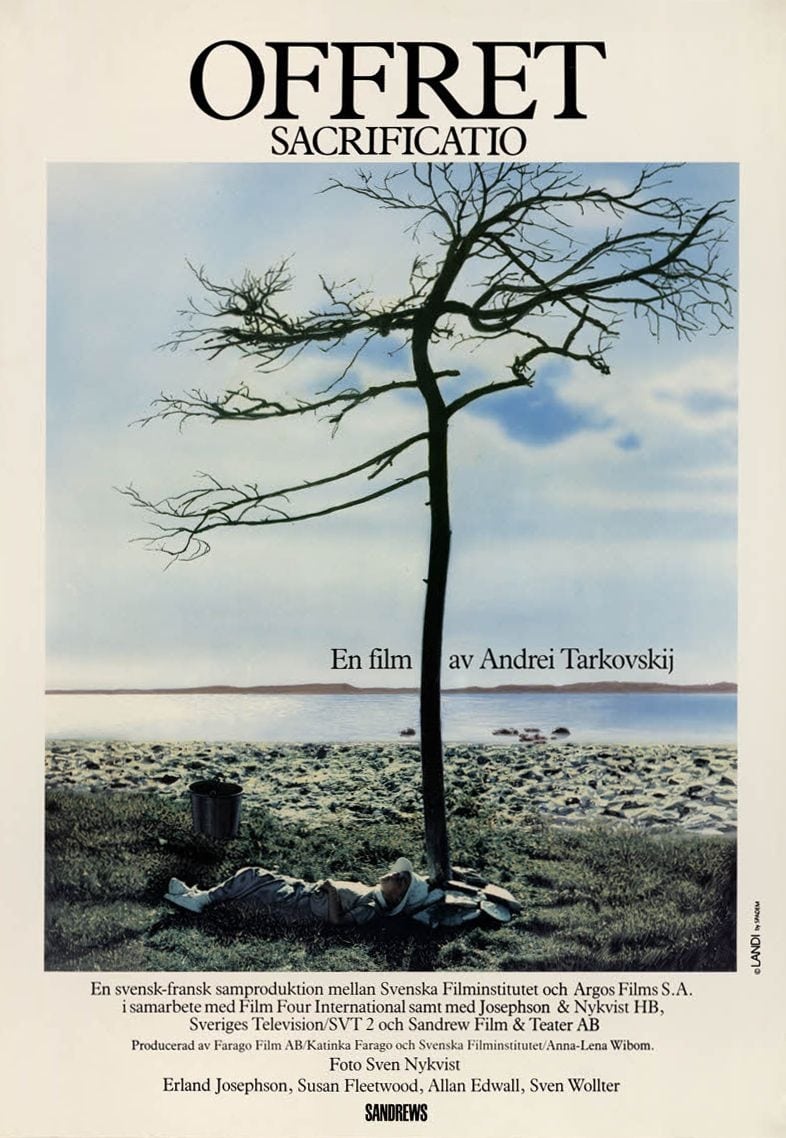

It's all extraordinary heavy - would we expect anything less from Tarkovsky's last film? But it also feels a bit unmodulated in its heaviness. While the film's impersonation of a stage drama is convincing, it lacks something that the director's best films are so good at, inhabiting their spaces with a kind of expansive quality. This is surely not an accident, for The Sacrifice has already drawn a clear distinction between its interiors and its exteriors - the very first shot, running the absolute maximum that a single reel of film could accommodate, would fit happily into Nostalghia or Mirror, particularly the former; it starts on an extreme long shot of Alexander (Josephson), and his inexplicably young son, never referred to by name, but as "Gossen" (Tommy Kjellqvist). The longstanding tradition has been to translate this as "Little Man", which does the film no favors - it is overburdened enough with fraught Christological symbolism as it is. It's more of a friendly generic term for "young male", I think in something close to the way an English speaker might say "m'boy" or "lad", but I would want you to check in with a native speaker of Swedish before quoting me on that. The point being, Alexander and son are planting a tall, slender tree in the vividly green grass beside a pair of ruts describing a road, near a bluff overlooking the sea, under a flat grey sky that makes the whole world glow with soft, diffuse light. They begin to walk to the left, and the camera tracks with them; they grow nearer, and still we track left. They are met by the local postman, Otto (Allan Edwall), who manages to provide the exposition that this is Alexander's birthday, and continue moving across, until they have closed most of the distance to land in a medium shot, in a completely new space. It is a masterpiece of a shot, and I hate to say that it's the film's artistic peak (the other candidate is the final 10 or 12 minutes, so at least the film makes a good first and last impression); but it is anyway quite a marvelous achievement, a way of sinking us into this space and thee characters while impressing upon us the element grandeur and cosmic scale of the setting.

The exteriors, then, are pure, vintage Tarkovsky, to contrast with the stultifying cod-Bergman interiors, and again, "stultifying" is clearly no mistake. The film is what it wants to be, and it wants to be an exhausting study of emotional desolation and interpersonal inadequacy. Alexander's party is a solemn, spare affair: the celebrants include his wife, Adelaide (Susan Fleetwood), his stepdaughter, Marta (Filippa Franzén), the Little Man's doctor, Victor (Sven Wollter), who is possibly having an affair with Adelaide, Otto, and the young maid Julia (Valérie Mairesse). The older maid Maria (Guðrún Gísladóttir), helps to set things up, but leaves before the party begins. It is more than a little curious that the men are all Swedish, and the women are a pan-European polyglot (and iffily-dubbed on top of it); whether we're even meant to notice this is tough to say, but given that the only real birthday event involves Alexander being given a handsomely framed map of Europe, which triggers one of his many monologues, it seems like we had better think at least a little bit about how that house seems to include all of the continent, or even all of humanity (and it was written and directed by a Russian exile living in France! I frankly have no idea what to make of all this, but God knows it's there to be made).

And this matters because, in no uncertain terms, The Sacrifice is a parable about humanity's behavior. During the party, several jets noisily fly over the house, shaking it so hard that a jug of milk crashes to the floor inside, spreading in a thick white puddle that gets favored with, I think, the first close-up of the entire movie. And when we cut away from that puddle, the film itself has absorbed its blankness - Tarkovsky and Nykvist worked hard to desaturate the hell out of the footage in post-production, leaving just enough of the ghost of color to make it clear how washed-out everything looks. As we're about to learn from a radio report, the world has gone to nuclear war, maybe; maybe it has even already destroyed itself. Maybe this little desolate patch of the Swedish coast is one of the last vestiges of humankind. So that visual emptiness is clearly meant to hammer at us with its bleakness.

It sure does hammer. Honestly, part of what I find unsatisfying about The Sacrifice is his direct and blunt it is. Tarkovsky's greatest films feel inevitable, but it also feels like they set us on a path and let us reach the end point on our own. The Sacrifice is inevitable and pushy about it. Hence: the profound depression that settles upon the characters as they contemplate the end of the world is marked by a bleak desaturation (and when color comes back, it does so at an equally blunt point). Hence giving Maria that name: not to spoil the movie, or anything, but it's kind of impossible to talk about the film's themes at all without going nearly to the last scene, so Alexander is told that, to save the entire world, he must go to remote cottage and have sex with her. Having done this, he must renounce all his possessions and never speak another word. He must make a profound sacrifice, you might say - the film sure does. The point being, we have the otherworldly Maria, through whose ethereal womanhood humanity is redeemed. Do you get it? Boy, you'd better get it.

I'm being awfully snitty about a film that is, any way you want to slice it, a truly plentiful and elaborate work of art; stylistically, ethically, and spiritually The Sacrifice is throwing a hell of a lot at us and demanding that we keep up with it. I suspect one could go a lot of rounds with this movie and still never quite get on top of the astonishing potency of its last act (everything after Alexander and Maria's night together), which completely abandons the stagebound aesthetic for something much closer to the domestic scenes in Mirror or Stalker, and benefit (considerably, I would say) from focusing less on characters' words than their behavior. It is a compromised and dubious masterwork, but there is much within it that is quite extraordinary, and I would give up neither the simple apocalypse of its fiery climax nor the quiet mystery of faith bound up in its final scene for anything.

Still, a lot of the scenario is rather trite. The bluntness of the Christian imagery, and even the more obliquely secular symbolism, goes beyond forcefulness into pandering hand-holding at times (the milk shattering is a groaner salvaged only by how visually beautiful it is). And I simply cannot fathom what we're supposed to do with the matter of Alexander's sacrifice and the transcendent sexual ritual that it hangs on. This is a powerfully overripe metaphor, even spotting the film its arguably too-neat decision to make this specific man jump through these arbitrary hoops to act as the salvation of all the world. Without question, I can understand how somebody might find it beautiful and transfixing and mysterious in the best possible way. Me, I hate to say it, but I really do think it's a little bit silly, too profoundly self-aware of its own artful indulgences to entirely get away with them. Bergman would have made this work... aye, but Bergman wouldn't have gotten himself on this track, The Virgin Spring notwithstanding. Let's say that he had, though. Bergman would have made this work by focusing on psychological realism, digging into Alexander's doubts and confusions at being made the avatar of his race. Tarkovsky and The Sacrifice don't care much about psychology; they want him to be an emblem, the embodiment of certain ideas about the fallen European intelligentsia and creative classes during an especially acrimonious and stressful period of the Cold War (he's an ex-professor, an ex-writer, and an ex-actor), a vessel for morality and empathy but not someone who himself generates those things. Josephson is a superb actor and makes this work, but a version of The Sacrifice with a less blatantly symbolic Alexander might have been a film where the symbolism might have felt less oppressive.

But I suppose Tarkovsky wanted to make a highly oppressive film, as was his right. This is, directly and without apology, an attempt to grapple with the personal fear of death and global apocalyptic paranoia at the same time. It is trying to do so much, presenting us with, of all things, an optimistic vision of the destruction of the world, and if it doesn't quite get to where it needs to, I can't think of another film that makes the attempt. It is a truly remarkable object, and a bravely uneasy capstone to a titanic career. Warts and all, it is a film to grapple with, maybe to love, and maybe to find transporting, uplifting, and devastating in ways most films don't even dare to strive for.

I begin this way in part because I think it's impossible not to have these kinds of thoughts running through your head while watching the film, but also to safeguard myself against my own doubts. The Sacrifice is an extraordinary and rich film with profound depths; it's also a frustrating film that seems distressingly blind to its own deficiencies, and finds the writer-director fighting to express himself in a borrowed idiom that he obviously admires without having completely taken it into himself. And that's to say nothing of its incredible scenario, with a second half that pivots on an event at once too outlandish to register as anything but the stuff of metaphor and parable, and too trite and self-regarding to take entirely seriously.

Now that I've started the review down two different and perhaps even mutually exclusive paths, let me start to try and tie them together. Aye, I have doubts about The Sacrifice - great doubts even. But they are doubts that are much, much easier to have about a film that demands comparison to what very well might be the strongest body of work in cinema history, Tarkovsky's five unmitigated masterpieces stretching from Andrei Rublev in 1966 to Nostalghia in 1983. Just because the director kept living up to the standard he set for himself doesn't mean that it's fair to demand he do so; the miracle is that he produced five films in a row at that level of achievement.

Anyway, I claimed that the film uses a borrowed idiom, something that I don't think anybody could possibly dispute; it is, like, really obvious that this Tarkovsky's version of an Ingmar Bergman film. And there's certainly nothing wrong with that, as such. Bergman himself openly acknowledged Tarkovsky's films as a major influence on his own thoughts (Ivan's Childhood specifically), and it's kind of fun to think of all one's favorite austere European filmmakers liked each other's work and stole the best ideas from each other. In the case of The Sacrifice (which is in Swedish, kick-starting the similarities), we have the theft of one of Bergman's favorite leading men, Erland Josephson (who had a medium-sized but hugely important role in Nostalghia), and Bergman's longstanding cinematographer, Sven Nykvist. Just as crucially, if less famously, the film's production design was by Anna Asp, who'd joined the Bergman family late, with 1978's Autumn Sonata, and who received a rather bold Oscar win for Fanny and Alexander. And the film plays, especially for an enormously long stretch in the middle, very much like the theatrical chamber dramas that were Bergman's great love, the particularly Scandinavian masterpieces typified by the work of Ibsen and Strindberg.

The last of these points explains why Asp was such an important contributor to the film. The Sacrifice takes place in the isolated home of a well-off family, with a handful of very long scenes on the land around it, and a short sequence in a different building. Mostly, though, we're in that home, and for all that I would never dream of short-changing Nykvist's contribution - which is unmistakably his, in the best way possible - I really do feel like the film's visual aesthetic relies most of all on Asp's sets. The house feels impossibly big from the inside compared to what we see of the outside, with large gaping rooms that seem to go forever into the back and sides, while crushing down from the top. It's also extremely austere in a handsome, well-appointed way, all bone-white walls and rich dark brown woodwork and very little in the way of furniture. It feels unabashedly like a stage, and a bare one at that, and Tarkovsky moves his characters around that space in heavily determined blocking that makes them feel like they are trapped in a pageant-like trance, not of their choosing. It is airy and claustrophobic at the same time, the latter impression helped out by Nykvist's gloomy, wintry lighting, which feels like pale blocks running hard into murky shadows on the edges.

It's all extraordinary heavy - would we expect anything less from Tarkovsky's last film? But it also feels a bit unmodulated in its heaviness. While the film's impersonation of a stage drama is convincing, it lacks something that the director's best films are so good at, inhabiting their spaces with a kind of expansive quality. This is surely not an accident, for The Sacrifice has already drawn a clear distinction between its interiors and its exteriors - the very first shot, running the absolute maximum that a single reel of film could accommodate, would fit happily into Nostalghia or Mirror, particularly the former; it starts on an extreme long shot of Alexander (Josephson), and his inexplicably young son, never referred to by name, but as "Gossen" (Tommy Kjellqvist). The longstanding tradition has been to translate this as "Little Man", which does the film no favors - it is overburdened enough with fraught Christological symbolism as it is. It's more of a friendly generic term for "young male", I think in something close to the way an English speaker might say "m'boy" or "lad", but I would want you to check in with a native speaker of Swedish before quoting me on that. The point being, Alexander and son are planting a tall, slender tree in the vividly green grass beside a pair of ruts describing a road, near a bluff overlooking the sea, under a flat grey sky that makes the whole world glow with soft, diffuse light. They begin to walk to the left, and the camera tracks with them; they grow nearer, and still we track left. They are met by the local postman, Otto (Allan Edwall), who manages to provide the exposition that this is Alexander's birthday, and continue moving across, until they have closed most of the distance to land in a medium shot, in a completely new space. It is a masterpiece of a shot, and I hate to say that it's the film's artistic peak (the other candidate is the final 10 or 12 minutes, so at least the film makes a good first and last impression); but it is anyway quite a marvelous achievement, a way of sinking us into this space and thee characters while impressing upon us the element grandeur and cosmic scale of the setting.

The exteriors, then, are pure, vintage Tarkovsky, to contrast with the stultifying cod-Bergman interiors, and again, "stultifying" is clearly no mistake. The film is what it wants to be, and it wants to be an exhausting study of emotional desolation and interpersonal inadequacy. Alexander's party is a solemn, spare affair: the celebrants include his wife, Adelaide (Susan Fleetwood), his stepdaughter, Marta (Filippa Franzén), the Little Man's doctor, Victor (Sven Wollter), who is possibly having an affair with Adelaide, Otto, and the young maid Julia (Valérie Mairesse). The older maid Maria (Guðrún Gísladóttir), helps to set things up, but leaves before the party begins. It is more than a little curious that the men are all Swedish, and the women are a pan-European polyglot (and iffily-dubbed on top of it); whether we're even meant to notice this is tough to say, but given that the only real birthday event involves Alexander being given a handsomely framed map of Europe, which triggers one of his many monologues, it seems like we had better think at least a little bit about how that house seems to include all of the continent, or even all of humanity (and it was written and directed by a Russian exile living in France! I frankly have no idea what to make of all this, but God knows it's there to be made).

And this matters because, in no uncertain terms, The Sacrifice is a parable about humanity's behavior. During the party, several jets noisily fly over the house, shaking it so hard that a jug of milk crashes to the floor inside, spreading in a thick white puddle that gets favored with, I think, the first close-up of the entire movie. And when we cut away from that puddle, the film itself has absorbed its blankness - Tarkovsky and Nykvist worked hard to desaturate the hell out of the footage in post-production, leaving just enough of the ghost of color to make it clear how washed-out everything looks. As we're about to learn from a radio report, the world has gone to nuclear war, maybe; maybe it has even already destroyed itself. Maybe this little desolate patch of the Swedish coast is one of the last vestiges of humankind. So that visual emptiness is clearly meant to hammer at us with its bleakness.

It sure does hammer. Honestly, part of what I find unsatisfying about The Sacrifice is his direct and blunt it is. Tarkovsky's greatest films feel inevitable, but it also feels like they set us on a path and let us reach the end point on our own. The Sacrifice is inevitable and pushy about it. Hence: the profound depression that settles upon the characters as they contemplate the end of the world is marked by a bleak desaturation (and when color comes back, it does so at an equally blunt point). Hence giving Maria that name: not to spoil the movie, or anything, but it's kind of impossible to talk about the film's themes at all without going nearly to the last scene, so Alexander is told that, to save the entire world, he must go to remote cottage and have sex with her. Having done this, he must renounce all his possessions and never speak another word. He must make a profound sacrifice, you might say - the film sure does. The point being, we have the otherworldly Maria, through whose ethereal womanhood humanity is redeemed. Do you get it? Boy, you'd better get it.

I'm being awfully snitty about a film that is, any way you want to slice it, a truly plentiful and elaborate work of art; stylistically, ethically, and spiritually The Sacrifice is throwing a hell of a lot at us and demanding that we keep up with it. I suspect one could go a lot of rounds with this movie and still never quite get on top of the astonishing potency of its last act (everything after Alexander and Maria's night together), which completely abandons the stagebound aesthetic for something much closer to the domestic scenes in Mirror or Stalker, and benefit (considerably, I would say) from focusing less on characters' words than their behavior. It is a compromised and dubious masterwork, but there is much within it that is quite extraordinary, and I would give up neither the simple apocalypse of its fiery climax nor the quiet mystery of faith bound up in its final scene for anything.

Still, a lot of the scenario is rather trite. The bluntness of the Christian imagery, and even the more obliquely secular symbolism, goes beyond forcefulness into pandering hand-holding at times (the milk shattering is a groaner salvaged only by how visually beautiful it is). And I simply cannot fathom what we're supposed to do with the matter of Alexander's sacrifice and the transcendent sexual ritual that it hangs on. This is a powerfully overripe metaphor, even spotting the film its arguably too-neat decision to make this specific man jump through these arbitrary hoops to act as the salvation of all the world. Without question, I can understand how somebody might find it beautiful and transfixing and mysterious in the best possible way. Me, I hate to say it, but I really do think it's a little bit silly, too profoundly self-aware of its own artful indulgences to entirely get away with them. Bergman would have made this work... aye, but Bergman wouldn't have gotten himself on this track, The Virgin Spring notwithstanding. Let's say that he had, though. Bergman would have made this work by focusing on psychological realism, digging into Alexander's doubts and confusions at being made the avatar of his race. Tarkovsky and The Sacrifice don't care much about psychology; they want him to be an emblem, the embodiment of certain ideas about the fallen European intelligentsia and creative classes during an especially acrimonious and stressful period of the Cold War (he's an ex-professor, an ex-writer, and an ex-actor), a vessel for morality and empathy but not someone who himself generates those things. Josephson is a superb actor and makes this work, but a version of The Sacrifice with a less blatantly symbolic Alexander might have been a film where the symbolism might have felt less oppressive.

But I suppose Tarkovsky wanted to make a highly oppressive film, as was his right. This is, directly and without apology, an attempt to grapple with the personal fear of death and global apocalyptic paranoia at the same time. It is trying to do so much, presenting us with, of all things, an optimistic vision of the destruction of the world, and if it doesn't quite get to where it needs to, I can't think of another film that makes the attempt. It is a truly remarkable object, and a bravely uneasy capstone to a titanic career. Warts and all, it is a film to grapple with, maybe to love, and maybe to find transporting, uplifting, and devastating in ways most films don't even dare to strive for.