Game of Death

I literally cannot imagine a world where The Seventh Seal didn't exist. It is, without a trace of hyperbole, one of the works that defines its medium. That there is a thing called "the art film"; that we can, without embarrassment, treat cinema as something that serious intellectuals can and should grapple with; that there is such a word and a concept as "cinephile", as distinct from "movie buff"; every one of these things tracks back directly to the enormous impact this film made as it opened across the globe in 1957, '58, and '59. Not since France in the silent era had there been such urgency behind treating a film as fine art. This does not, I should hasten to point out, have all that much to do with The Seventh Seal itself. The previous ten years had been paving the way for this development, between the game-changing impact of Italian Neorealism, the post-war avant-garde, the rise of film festivals throughout Europe, and the exports from Japan that were introducing the West to that nation's amazing visual traditions. Something, by the end of the '50s, was going to open the gates to the golden age of '60s art house cinema and the invention of film studies as an academic discipline. It just happened to be this film that did it, with its overt symbolism, its desperately heavy themes of God, faith, and death, and its immediate declaration that we are going to be Pondering it for many hours - days! - weeks! - after leaving the theater.

The film's reputation precedes it, in other words. And just as much as we live in a world that has been to some degree defined by The Seventh Seal, so too do we live in a world where The Seventh Seal has something of the stink of being the ultimate in "been there, done that". Worse still, it has the unlovable tragedy of having become An Official Classic, the kind of art - be it a novel, a painting, a symphony, or, yes, a movie - that is meant to be dutifully respected but not at all enjoyed, and also to be diminished as hard as possible by comparing it to fifteen other, newer artworks doing the same thing but bolder, fresher, more successfully.

Our first job, then, is to attempt to hack away 63 years of accreted Respectability, and try to get at the actual thing that is The Seventh Seal, and not The Seventh Seal™®©. For, as an unrepentant and genuine lover of many Official Classics, from Great Expectations to Beethoven's Ninth, I take it as given that the reason these things gained their ossified, monolithic reputations is that there has to be something there that people responded to in the first place. In this case, let's go back even further than 1957; let's go all the way to 1953, the year that Bergman took over as director of the Malmö City Theatre. One of his projects here was to create training workshops for actors, and to this end, he wrote a short play, Wood Painting, that was inspired by artwork he saw on the walls of a church from the Middle Ages. Set during the Black Death, it consists of several monologues delivered by various members of medieval Swedish society, centered on the return of a knight and his squire from the Crusades (there was no overlap between the Crusades and the Black Death; that's okay, it's an allegory). Shortly thereafter, Bergman polished it enough for it to be produced, on the radio and onstage.

A couple of years later, following his smash hit comedy Smiles of a Summer Night, the director found himself unhappily in a rut. Light comedy wasn't what he was interested in; but producers were having none of his ultra-dour heavy dramas. As he told the story in later years, it was his lover, the actress Bibi Andersson (who had a tiny part in Smiles) who encouraged him to take his newfound clout to Svensk Filmindustri, and try to get a film on the same themes as Wood Painting financed, having been shot down once before. This time, he got the green light, albeit with hardly any money and a rushed shooting schedule, and his much expanded new version of the story went into production in the second half of 1956. It was released to lukewarm reviews in Sweden the following winter, but it also found its way to the 1957 Cannes International Film Festival, and the rest you know.

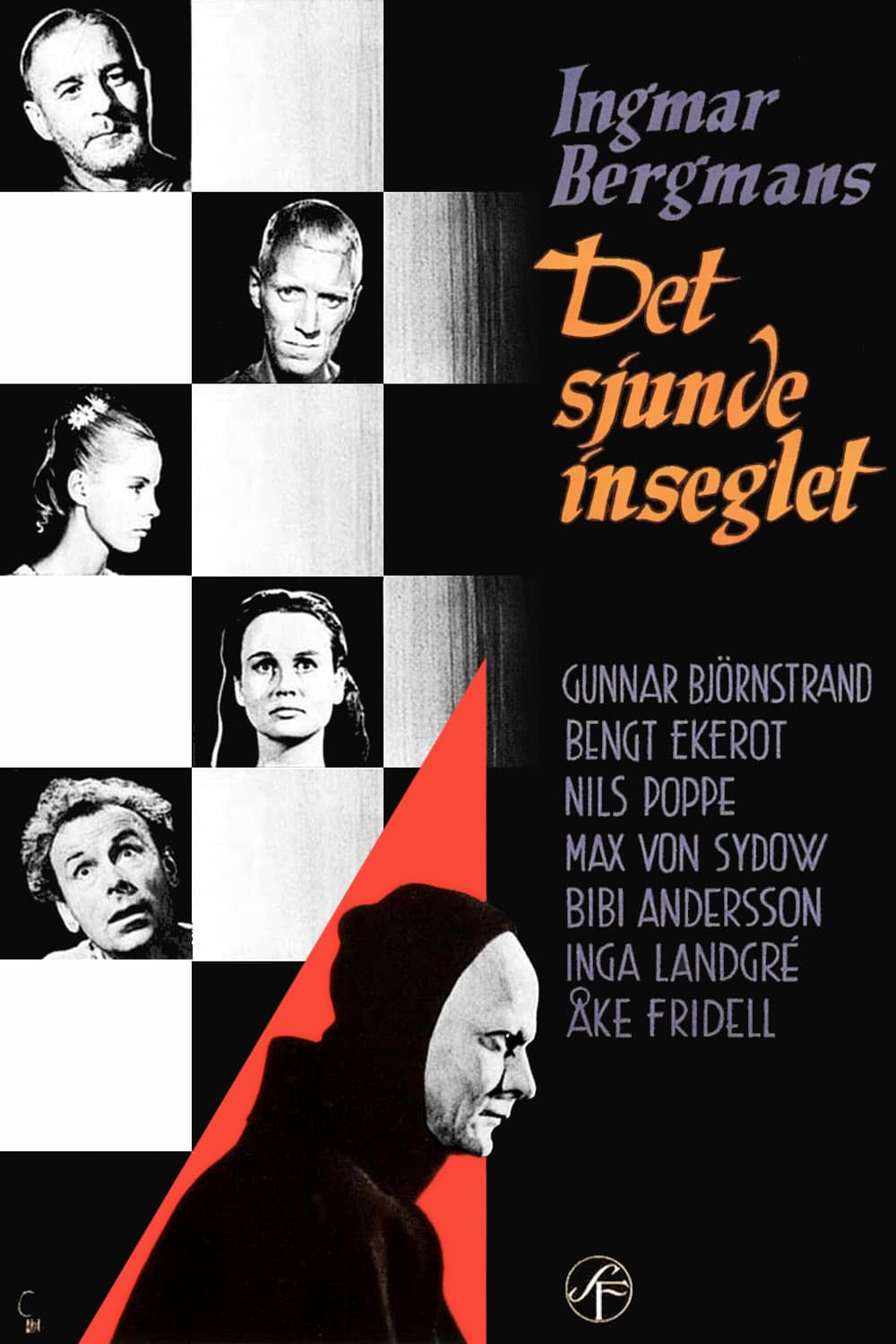

Something one notices when approaching The Seventh Seal from the perspective of "Ingmar Bergman's follow-up to Smiles of a Summer Night that the studio only financed reluctantly", rather than the perspective of "this is a canonised masterpiece", is that Bergman had not, by any means, shaken loose the experiments in comedy that he had awkwardly forced himself into. In fact, and I had entirely forgotten this in the 15 years or so since I last watched the film, The Seventh Seal can be really fucking funny. It can also be a morbid, solemn dirge, and this is the mode it wants to impress upon us right at the start: first in a series of grave, austere opening credits, thin white text on a black background, with no music (the first time Bergman used what was to become his signature opening credits aesthetic). Then the sound track blares forth with choral voices screaming "Dies Irae", alongside the image of a heavily overcast sky; this dissolves to more clouds, with a bird of prey hovering in place against them, a black smudge of death against the grey.

So no, it's definitely not a comedy. But it can, unquestionably, tell a joke when the need arises. This easy conflation of the extremely grim and depressing with sometimes outright dumb humor is strange enough just on its own terms, let alone from a director who had already earned a reputation as an unsmiling misery-monger (and some of his '60s films would make his tragic melodramas look absolutely peppy). It is, however, a perfect fit for this particular project of all projects. The story is still that a knight, Antonius Block (Max von Sydow), and his squire, Jöns (Gunnar Björnstrand) have just returned from the Crusades, to find the southern coast of Sweden ravaged by the plague. The country is in a positively apocalyptic mood - "the seventh seal" is a reference to the Book of Revelation, a passage recited out loud at the film's opening - and people from every stratum of society are dealing with the widespread death and devastation in a number of ways, almost all of which involve the unseen, unspeaking God permitting (or causing) this to happen. It is, essentially, a medieval morality play, freshened up with post-WWII agnosticism and paranoia. And it therefore does as a medieval play does, combining the very high and the very low, to end up with something that's grappling with the mysteries of faith while also throwing in some outright wackiness to keep us from losing interest.

That's two highly divergent tones; Bergman adds a third. The Seventh Seal is not, after all, a medieval play, but a midcentury movie, and it bring in a midcentury attitude to provide something of a biting, sarcastic commentary all through the rest of the movie. I refer here to Jöns, whose relationship to the rest of the film is as a discomfitingly self-aware participant in a fiction. From a very early point, the script feeds him lines that feel, more than anything, like Bergman second-guessing his own project and his intentions in putting it together: when Jöns critiques a mural painter for depicting the Black Death on the walls of a church, the words he uses go far beyond the needs of the scene: so why ask people to watch something unpleasant that reminds them of the inevitability of death? Does it actually do any good?

Bleak religious existentialism, broad comedy, and sarcasm: the three pillars of The Seventh Seal, and Bergman combines them in a beautiful mixture that somehow manages to never feel forced or clumsy. It is not, crucially, using humor to diminish the main thrust of the story, which is so famous - maybe the most famous thing in Begman's entire career, or in '50s European cinema - that I a feel a trifle silly even saying it. Upon arriving in Sweden, Block is about to die, and when Death comes for him - in the form of a pale, tight-skinned face emerging from the top of a sweeping black robe, played to perfection by Bengt Ekerot - the knight rather proudly suggests a game of chess. If he wins, he lives. If Death wins, at least they've had a good time.

This throughline is responsible for some of the most famous images in all of cinema, and more parodies than I can possibly imagine counting (though Bergman invented nothing; the image of a knight playing chess with Death came to him from - that's right - a painting in a medieval church), so its honestly a miracle that it still works a well as it does. The smart way that the film uses this as a structural element is part of it; the chess game isn't the movie, but the punctuation mark that splits the movie into segments, developing as it goes. The meat of the film follows as Block, hoping to stay alive just long enough to learn why God has allowed this misery to befall His creation, gains non-answers from different sorts of people; the interludes with Death are the places where the film and Block take stock of what we have(n't) learned. This reaches two different climaxes: first, when Block finally asks Death directly what the spiritual order of the cosmos is, and in the bleakest of all the darkly comic punchlines, Death not only doesn't know, he seems a bit baffled why someone would want to ask him. Second, when the pilgrimage that Block has assembled over the course of the film finally reaches the point where they must die, each one of them readies for death in their own way, certain of whatever they have been certain of throughout the film - Block, who has no certainty, only pure doubt, is the only member of the group to react with terror and panic. A nasty little trick to end on, and maybe an autocritical one, since the film itself finds Bergman asking questions right along with Block, even as he uses Jöns to mock himself for the asking.

So the Death scenes are used superbly well. The other thing that makes them so rich is how extremely good von Sydow and Ekerot are at playing them: they're intellectual battles, thrilling and fun to watch. I think I would have a hard time overstating how good Ekerot is in this film: his little smiles of amusement and smug superiority (not always at the same time) are obvious, but I love best all the moments that he lets us see a weirdly human side to Death. My favorite moment in the performance - probably my favorite moment in the film - is when Death whips out a bow saw to cut down the tree where a man less cunning than Block has gone to hide. Beyond the inherent silliness of the moment, Ekerot does amazing work in portraying Death as a happy worker, relishing the chance to put in some elbow grease to make sure the job is done well. This is maybe the best way that The Seventh Seal questions itself: its a film about death as an unfathomable force of destruction that also portrays Death in an earthy, unfussy way: he's the terror the destroys all happiness, but he's also a wry wit, irritable, and he cheats at chess. It's the finest depiction of Death as a conscious force in any 20th Century artwork I can name until the British comic novelist Terry Pratchett took a crack at the character (and there's undeniably some of Bergman's Death in Pratchett's).

In between these moments where Block and Death have their snide little banter, The Seventh Seal presents Bergman's first sustained treatment of one of the great themes of art: how are we to know God? The film is structured as a series of episodes each finding a different way to answer this, though it flows so smoothly through so many vibrantly-etched characters that it never feels episodic. The only characters we ever meet who are absolutely positive that God is an active force also take it for granted that He's wrathful and destructive: the penitents who bluntly interrupt one scene in a parade, whipping and otherwise debasing themselves, till they disappear in a dust cloud that dissolve into empty dirt (this film is, among its other traits, an extended experiment in playing around with dissolves; it is Bergman's only collaboration with editor Lennart Wallén, which might explain why it's cut so differently from all of the director's earlier films). For the pessimistic humanist Jöns, God is a null hypothesis, to be dismissed and disproven. But for all that Jöns is positioned as the voice of reason "outside" the film, answering from the 1950s, I think the characters we're really meant to side with are the family of jugglers, Jof (Nils Poppe) and Mia (Bibi Andersson) and their infant son Mikael. For one thing, the film obviously gives them pride of place near the end. They represent the simplest way through these horrible conundrums of death and suffering and God's place in a godless universe: ignoring all of it and just do your best. Jof and Mia are plain, likable people, clowns in a world of grandeur and pageantry, the only humans in a film of abstract ideas. Poppe was one of Sweden's biggest comedy stars at the time, and while Death and Jöns get all the film's acerbic wit, he gets all of its warm, goofy humor; he and Andersson do not remotely suggest an actual romantic couple (she is too virginal and practically glowing with motherly innocence; if the film weren't so blatantly an allegory first and a drama second, it might bother me more), but they exude warmth and camaraderie together, and for the second film in a row, Bergman plainly suggests that the wisdom of unsophisticated rustics counts for more than the philosophical wit of the educated in actually getting through every day alive, and happy to be alive.

The film isn't nearly as schematic as I've just made it sound, though being an allegory, it can't afford to hide its themes too subtly. And indeed, it is not subtle film, except in Björnstrand's performance (which is more central than von Sydow's or Poppe's), which is all about the introduction of modernist ambivalence into the broad strokes of medieval theater. There is also, perhaps, some subtlety to be found in Gunnar Fischer's luminous cinematography, easily the highlight of his work with Bergman. In a film taking all of its narrative cues from medieval painting, it's more than a little ironic that it takes not a single visual cue fro medieval painting; instead, it's a mixture of beautiful sun-dappled naturalism and highly expressionist splashes of darkness to underline the morbid setting. I have seen it said in multiple places, I do not know how reliably, that Bergman and Fischer were inspired by Kurosawa, Rashomon in particular, and this film's woodland scenes are absolutely drawing from the same set of aesthetic tricks as that film, presenting something that's at once completely realistic while also feeling psychologically expressive. Like that film, The Seventh Seal also has several different registers, some of them not nearly so realistic (the inside of Block's castle is a void of pure negative space), and this film relies far more extensively on large-scale contrasts between black and white, at the level of scenes (the play that Jof and Mia give is so bright that even blacks are rendered as dark greys; compare this to the tavern where Jöns meets Jof's opposite number, the cuckolded blacksmith Plog (Åke Fridell), a murky collection of underlit corners, with isolated pools of white), all the way down to the high-contrast figure of Death himself.

The forest, then, matters because, like the stony beach near the beginning and end, it forces grey into this story; and grey is the main mood here, ambivalence and uncertainty reining even above the catastrophe of widespread death. Indeed, in all ways, The Seventh Seal is an especially grey movie; funny and miserable, optimistic and fatalistic. The exquisite visual schema feeds into that, but it's true at every level of writing, film craft, and acting; considering how openly this is a patchwork of ideas and moods, it's astonishing how unified it all ends up feeling.

The film's reputation precedes it, in other words. And just as much as we live in a world that has been to some degree defined by The Seventh Seal, so too do we live in a world where The Seventh Seal has something of the stink of being the ultimate in "been there, done that". Worse still, it has the unlovable tragedy of having become An Official Classic, the kind of art - be it a novel, a painting, a symphony, or, yes, a movie - that is meant to be dutifully respected but not at all enjoyed, and also to be diminished as hard as possible by comparing it to fifteen other, newer artworks doing the same thing but bolder, fresher, more successfully.

Our first job, then, is to attempt to hack away 63 years of accreted Respectability, and try to get at the actual thing that is The Seventh Seal, and not The Seventh Seal™®©. For, as an unrepentant and genuine lover of many Official Classics, from Great Expectations to Beethoven's Ninth, I take it as given that the reason these things gained their ossified, monolithic reputations is that there has to be something there that people responded to in the first place. In this case, let's go back even further than 1957; let's go all the way to 1953, the year that Bergman took over as director of the Malmö City Theatre. One of his projects here was to create training workshops for actors, and to this end, he wrote a short play, Wood Painting, that was inspired by artwork he saw on the walls of a church from the Middle Ages. Set during the Black Death, it consists of several monologues delivered by various members of medieval Swedish society, centered on the return of a knight and his squire from the Crusades (there was no overlap between the Crusades and the Black Death; that's okay, it's an allegory). Shortly thereafter, Bergman polished it enough for it to be produced, on the radio and onstage.

A couple of years later, following his smash hit comedy Smiles of a Summer Night, the director found himself unhappily in a rut. Light comedy wasn't what he was interested in; but producers were having none of his ultra-dour heavy dramas. As he told the story in later years, it was his lover, the actress Bibi Andersson (who had a tiny part in Smiles) who encouraged him to take his newfound clout to Svensk Filmindustri, and try to get a film on the same themes as Wood Painting financed, having been shot down once before. This time, he got the green light, albeit with hardly any money and a rushed shooting schedule, and his much expanded new version of the story went into production in the second half of 1956. It was released to lukewarm reviews in Sweden the following winter, but it also found its way to the 1957 Cannes International Film Festival, and the rest you know.

Something one notices when approaching The Seventh Seal from the perspective of "Ingmar Bergman's follow-up to Smiles of a Summer Night that the studio only financed reluctantly", rather than the perspective of "this is a canonised masterpiece", is that Bergman had not, by any means, shaken loose the experiments in comedy that he had awkwardly forced himself into. In fact, and I had entirely forgotten this in the 15 years or so since I last watched the film, The Seventh Seal can be really fucking funny. It can also be a morbid, solemn dirge, and this is the mode it wants to impress upon us right at the start: first in a series of grave, austere opening credits, thin white text on a black background, with no music (the first time Bergman used what was to become his signature opening credits aesthetic). Then the sound track blares forth with choral voices screaming "Dies Irae", alongside the image of a heavily overcast sky; this dissolves to more clouds, with a bird of prey hovering in place against them, a black smudge of death against the grey.

So no, it's definitely not a comedy. But it can, unquestionably, tell a joke when the need arises. This easy conflation of the extremely grim and depressing with sometimes outright dumb humor is strange enough just on its own terms, let alone from a director who had already earned a reputation as an unsmiling misery-monger (and some of his '60s films would make his tragic melodramas look absolutely peppy). It is, however, a perfect fit for this particular project of all projects. The story is still that a knight, Antonius Block (Max von Sydow), and his squire, Jöns (Gunnar Björnstrand) have just returned from the Crusades, to find the southern coast of Sweden ravaged by the plague. The country is in a positively apocalyptic mood - "the seventh seal" is a reference to the Book of Revelation, a passage recited out loud at the film's opening - and people from every stratum of society are dealing with the widespread death and devastation in a number of ways, almost all of which involve the unseen, unspeaking God permitting (or causing) this to happen. It is, essentially, a medieval morality play, freshened up with post-WWII agnosticism and paranoia. And it therefore does as a medieval play does, combining the very high and the very low, to end up with something that's grappling with the mysteries of faith while also throwing in some outright wackiness to keep us from losing interest.

That's two highly divergent tones; Bergman adds a third. The Seventh Seal is not, after all, a medieval play, but a midcentury movie, and it bring in a midcentury attitude to provide something of a biting, sarcastic commentary all through the rest of the movie. I refer here to Jöns, whose relationship to the rest of the film is as a discomfitingly self-aware participant in a fiction. From a very early point, the script feeds him lines that feel, more than anything, like Bergman second-guessing his own project and his intentions in putting it together: when Jöns critiques a mural painter for depicting the Black Death on the walls of a church, the words he uses go far beyond the needs of the scene: so why ask people to watch something unpleasant that reminds them of the inevitability of death? Does it actually do any good?

Bleak religious existentialism, broad comedy, and sarcasm: the three pillars of The Seventh Seal, and Bergman combines them in a beautiful mixture that somehow manages to never feel forced or clumsy. It is not, crucially, using humor to diminish the main thrust of the story, which is so famous - maybe the most famous thing in Begman's entire career, or in '50s European cinema - that I a feel a trifle silly even saying it. Upon arriving in Sweden, Block is about to die, and when Death comes for him - in the form of a pale, tight-skinned face emerging from the top of a sweeping black robe, played to perfection by Bengt Ekerot - the knight rather proudly suggests a game of chess. If he wins, he lives. If Death wins, at least they've had a good time.

This throughline is responsible for some of the most famous images in all of cinema, and more parodies than I can possibly imagine counting (though Bergman invented nothing; the image of a knight playing chess with Death came to him from - that's right - a painting in a medieval church), so its honestly a miracle that it still works a well as it does. The smart way that the film uses this as a structural element is part of it; the chess game isn't the movie, but the punctuation mark that splits the movie into segments, developing as it goes. The meat of the film follows as Block, hoping to stay alive just long enough to learn why God has allowed this misery to befall His creation, gains non-answers from different sorts of people; the interludes with Death are the places where the film and Block take stock of what we have(n't) learned. This reaches two different climaxes: first, when Block finally asks Death directly what the spiritual order of the cosmos is, and in the bleakest of all the darkly comic punchlines, Death not only doesn't know, he seems a bit baffled why someone would want to ask him. Second, when the pilgrimage that Block has assembled over the course of the film finally reaches the point where they must die, each one of them readies for death in their own way, certain of whatever they have been certain of throughout the film - Block, who has no certainty, only pure doubt, is the only member of the group to react with terror and panic. A nasty little trick to end on, and maybe an autocritical one, since the film itself finds Bergman asking questions right along with Block, even as he uses Jöns to mock himself for the asking.

So the Death scenes are used superbly well. The other thing that makes them so rich is how extremely good von Sydow and Ekerot are at playing them: they're intellectual battles, thrilling and fun to watch. I think I would have a hard time overstating how good Ekerot is in this film: his little smiles of amusement and smug superiority (not always at the same time) are obvious, but I love best all the moments that he lets us see a weirdly human side to Death. My favorite moment in the performance - probably my favorite moment in the film - is when Death whips out a bow saw to cut down the tree where a man less cunning than Block has gone to hide. Beyond the inherent silliness of the moment, Ekerot does amazing work in portraying Death as a happy worker, relishing the chance to put in some elbow grease to make sure the job is done well. This is maybe the best way that The Seventh Seal questions itself: its a film about death as an unfathomable force of destruction that also portrays Death in an earthy, unfussy way: he's the terror the destroys all happiness, but he's also a wry wit, irritable, and he cheats at chess. It's the finest depiction of Death as a conscious force in any 20th Century artwork I can name until the British comic novelist Terry Pratchett took a crack at the character (and there's undeniably some of Bergman's Death in Pratchett's).

In between these moments where Block and Death have their snide little banter, The Seventh Seal presents Bergman's first sustained treatment of one of the great themes of art: how are we to know God? The film is structured as a series of episodes each finding a different way to answer this, though it flows so smoothly through so many vibrantly-etched characters that it never feels episodic. The only characters we ever meet who are absolutely positive that God is an active force also take it for granted that He's wrathful and destructive: the penitents who bluntly interrupt one scene in a parade, whipping and otherwise debasing themselves, till they disappear in a dust cloud that dissolve into empty dirt (this film is, among its other traits, an extended experiment in playing around with dissolves; it is Bergman's only collaboration with editor Lennart Wallén, which might explain why it's cut so differently from all of the director's earlier films). For the pessimistic humanist Jöns, God is a null hypothesis, to be dismissed and disproven. But for all that Jöns is positioned as the voice of reason "outside" the film, answering from the 1950s, I think the characters we're really meant to side with are the family of jugglers, Jof (Nils Poppe) and Mia (Bibi Andersson) and their infant son Mikael. For one thing, the film obviously gives them pride of place near the end. They represent the simplest way through these horrible conundrums of death and suffering and God's place in a godless universe: ignoring all of it and just do your best. Jof and Mia are plain, likable people, clowns in a world of grandeur and pageantry, the only humans in a film of abstract ideas. Poppe was one of Sweden's biggest comedy stars at the time, and while Death and Jöns get all the film's acerbic wit, he gets all of its warm, goofy humor; he and Andersson do not remotely suggest an actual romantic couple (she is too virginal and practically glowing with motherly innocence; if the film weren't so blatantly an allegory first and a drama second, it might bother me more), but they exude warmth and camaraderie together, and for the second film in a row, Bergman plainly suggests that the wisdom of unsophisticated rustics counts for more than the philosophical wit of the educated in actually getting through every day alive, and happy to be alive.

The film isn't nearly as schematic as I've just made it sound, though being an allegory, it can't afford to hide its themes too subtly. And indeed, it is not subtle film, except in Björnstrand's performance (which is more central than von Sydow's or Poppe's), which is all about the introduction of modernist ambivalence into the broad strokes of medieval theater. There is also, perhaps, some subtlety to be found in Gunnar Fischer's luminous cinematography, easily the highlight of his work with Bergman. In a film taking all of its narrative cues from medieval painting, it's more than a little ironic that it takes not a single visual cue fro medieval painting; instead, it's a mixture of beautiful sun-dappled naturalism and highly expressionist splashes of darkness to underline the morbid setting. I have seen it said in multiple places, I do not know how reliably, that Bergman and Fischer were inspired by Kurosawa, Rashomon in particular, and this film's woodland scenes are absolutely drawing from the same set of aesthetic tricks as that film, presenting something that's at once completely realistic while also feeling psychologically expressive. Like that film, The Seventh Seal also has several different registers, some of them not nearly so realistic (the inside of Block's castle is a void of pure negative space), and this film relies far more extensively on large-scale contrasts between black and white, at the level of scenes (the play that Jof and Mia give is so bright that even blacks are rendered as dark greys; compare this to the tavern where Jöns meets Jof's opposite number, the cuckolded blacksmith Plog (Åke Fridell), a murky collection of underlit corners, with isolated pools of white), all the way down to the high-contrast figure of Death himself.

The forest, then, matters because, like the stony beach near the beginning and end, it forces grey into this story; and grey is the main mood here, ambivalence and uncertainty reining even above the catastrophe of widespread death. Indeed, in all ways, The Seventh Seal is an especially grey movie; funny and miserable, optimistic and fatalistic. The exquisite visual schema feeds into that, but it's true at every level of writing, film craft, and acting; considering how openly this is a patchwork of ideas and moods, it's astonishing how unified it all ends up feeling.