Comedy of remarriage

The first half of the 1950s was the most troubled time in Ingmar Bergman's entire career, business-wise if not artistically, and things bottomed out in 1953. This was when Sawdust and Tinsel released, and became the first unmitigated disaster of his career: resoundingly rejected by audiences and treated coldly by critics (that it was his finest film to that point is, alas, of no matter). This was not a surprise: his regular studio, Svensk Filmindustri, wouldn't even touch the project, on account of its dismal financial prospects. In between the filming of Sawdust and Tinsel and its release, Carl Anders Dymling, head of Svensk Filmindustri, suggested that the time had come for Bergman to consider moving away from the glum, miserabilist shtick that had already become something of a cliché in his films, and something actually pleasant for a change. Needing to get back on his feet, Bergman accepted. Coupled with his new position as director of Malmö City Theatre, the end of 1953 was thus something of an opportunity for a career rebirth.

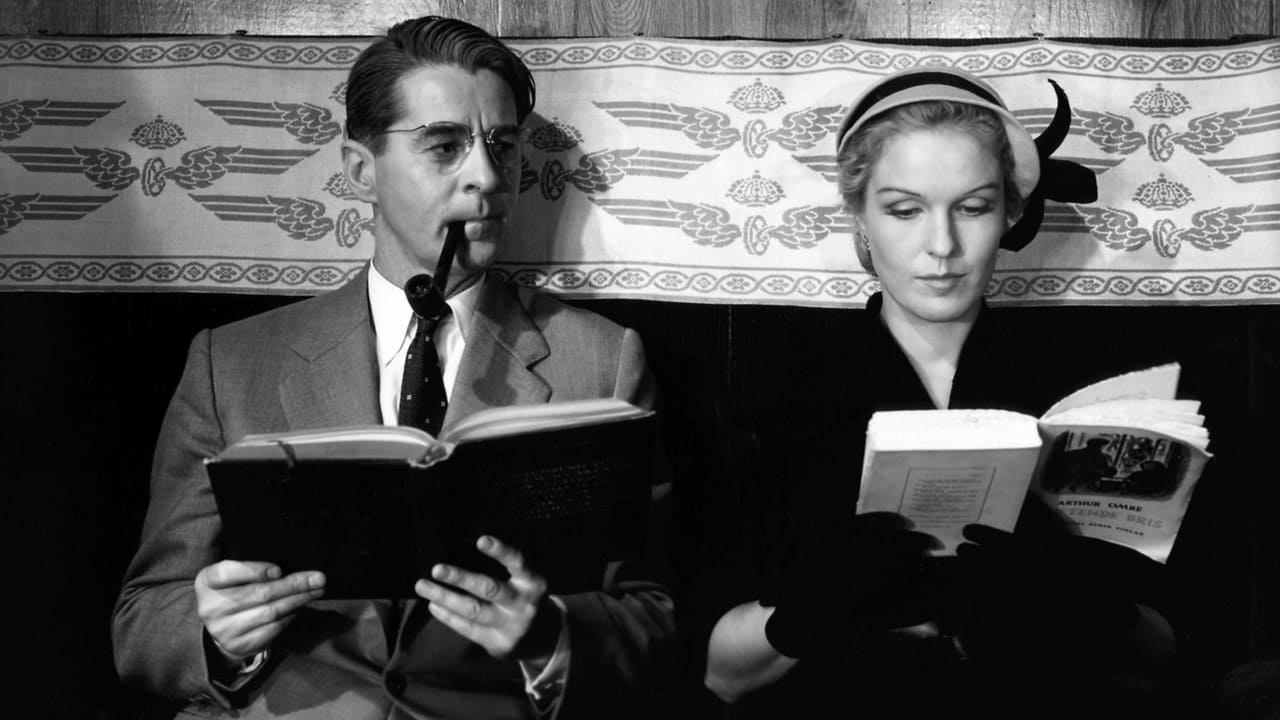

On the cinematic side of things, that rebirth was signified by A Lesson in Love, Bergman's sole film released in 1954. In broad strokes (and specific details, as well), it's pretty much exactly what one would expect this writer - and more to the point, this writer with this taste in plays - to make as his first unabashedly funny project: an elegant sex comedy, gamely poking fun at the institution of marriage and the troubles people cause themselves through ego. The ego in this case largely belongs to David Erneman (Gunnar Björnstrand), a gynecologist who starts the film by calling off his current affair with the younger Susanne (Yvonne Lombard). Later, he gets on a train to Copenhagen, sharing a compartment with a man we don't need to worry about (Helge Hagerman), and a woman named Marianne (Eva Dahlbeck), who seems both unusually receptive and unusually dismissive of David's clumsy attempts to flirt. We'll learn, in a little bit, that this is because Marianne is David's wife, sick of his bored, transparent philandering, and preparing to leave him to be with her own lover. The rest of the film covers one day and fifteen years, as the Ernemans spent the trip to Copenhagen reflecting on the shared history that has brought them to this point, as he attempts to win her back.

The chronologically untethered flashbacks that flesh out this history are both the most interesting aspect of A Lesson in Love, aesthetically speaking, and probably its most obvious liability. The film has essentially set itself a problem to solve, in the form of David: how do you introduce a protagonist by making him seem strongly unlikable, and then find a way to make us root for him as he tries to make amends to his wife, a woman who has every justification for hating him? The film pulls no punches: the first thing it does after the opening credits is to present Susanne staring directly into the camera, accusing David - that is, the viewer - of being an uncaring bastard. The camera spins around after a moment of this to reveal that she's been talking to David's back, and just like that, by the end of the first shot, we are aware that he is a standoffish prick with a dreadful attitude about women. This doesn't get softened anytime soon, either; the first achronological scene (not clearly flagged as such, either) finds David and the couple's teenage daughter, Nix (Harriet Andersson) chatting over lunch, and part of her irritable adolescent diatribe consists of confronting him with the fact that she and Marianne and everyone else knows his a prick; Björnstrand does a superb job of reacting to this, as both a "well, obviously" moment, and a tiny hint of surprise that he's not keeping it a secret.

And so back to the puzzle the film sets for us: how to make us want this marriage to survive? And we sense that it will, given the very opening: the credits are interrupted by the voice of Bergman himself, letting us know in advance that we're about to watch a comedy, on account of the fact that it ends happily; otherwise it would be a tragedy (an echo and inversion of the narrator telling us Crisis, eight years earlier was just a light drama, "almost a comedy"; it reiterates the feeling that A Lesson in Love is functioning as a second debut). There's a little bit of desperation here, sure - "I'm Ingmar Bergman, and I can too laugh" - but it's also priming us to take none of what follows all that very seriously, including David's most obnoxious qualities. The use of flashbacks to soften the present-day material do a lot as well, both by keeping us from spending too much time at once with the most toxic form of the marriage, as well as showcasing the excellent chemistry between Dahlbeck and Björnstrand.

The film would be quite unimaginable without them as leads; it was even designed specifically to bring them back, after they worked so well in the comic segment of Bergman's 1952 anthology film Waiting Women. The only production story Bergman ever really talked about was all about how much he needed them: he had been wrestling with one of the scenes, and could not figure out to save his life how to make it funny. He was ready to junk it when the actors nicely asked him to leave, and they'd figure it out; an hour later, they let him come back to set, ready to film the scene exactly as they'd blocked it, and it was perfect. The moral of the story, to Bergman, was that this was the moment that taught him to give himself over to the collaborative process, letting his actors find their characters and then show him how the movie needed to be fashioned around them, and this is a tremendously valuable lesson for the man who would thereafter become one of the greatest directors of actors to have learned. But it also tells us something about A Lesson in Love just by itself: the film lives and dies on the spectacular comic chemistry of its leads. The most important part of any successful romantic comedy, ultimately, is that we like watching the couple together, and I absolutely loved these two: their perfectly relaxed cadence with each other even in their most sniping moments really is very lovely, especially when the film thoughtfully contrasts it with an early scene in their relationship, to showcase how that cadence is the result of long-simmering familiarity.

They're also both excellent performances individually: Dahlbeck's, in particular, is a strong argument that she belongs in the conversation about Bergman's finest actresses, and this isn't even one of the best films they made together! A major reason she's generally overlooked, I am certain, is that of their five collaborations - seven if you count the ones he only wrote the screenplay for - only Smiles of a Summer Night is one of Bergman's Consensus Masterpieces; another, on full display here, is that she's not really even a little bit neurotic or tormented, but simply has an easygoing way of accepting what happens, processing it (generally with a tightening of her mouth that makes it look like she's literally chewing things over) and moving on. It's a very graceful, open, high-spirited performance, of a sort that feels like top-tier work by a major Hollywood star of the '30s or '40s, and one does not typically look to a Bergman film for grace. But I love what Dahlbeck is up to here, humanising David through her lingering, slightly melancholy affection for him, while also letting us see why she's sick of his bullshit and making Marianne such a fully-realised personality through her interaction with non-David characters that we get an absolutely full and complete sense of how she feels about herself and the world on days when she's not on the brink of divorcing her husband.

Dahlbeck's work - and Björnstrand's, though he's mostly just up to doing a very good version of pretty standard "pathetic male egotist has his ego punctured, to his self-conscious benefit" arc - gets to the most important thing that makes A Lesson in Love work: it still takes itself seriously as a marital drama, despite being a breezy, at times quite weightless comedy. And I should say that I was not expecting to find the film nearly as funny as I did - Bergman is no more known for being funny now than he was in 1954, and the one thing he made before this point that wasn't a heavy drama, his series of Bris Soap commercials, is more playful and delightful than "funny". The comic sequence from Waiting Women never got more than a mild nod of intellectual amusement from me. But there are gags in A Lesson in Love that worked perfectly for me: those that are surprising, those that are humorously inevitable, and those that are just plain dumb (there are two slapstick fistfights, echoing each other in an unforced way).

Still, when the film announces itself at the very start as a comedy for grown-ups, it means it: the Ernemans' marriage is defined with just as much sincerity as any relationship in any prior Bergman film, and the care with which it is developed through the film assumes that we hope to learn a little bit more about marriages in general than we did going in (the "lesson" isn't just the characters'). There are graceful pieces of filmmaking surrounding this, including near the end, a remarkable shift from a painfully extreme long shot to a much closer, intimate shot framed around the couple's bodies, at the exact moment they decide to reconcile, that does as much as any piece of acting to sell us on the fundamental stability of this relationship.

That being said, among the film's flaws, one of the biggest is that it's pretty flat, stylistically. I do not know if Bergman wanted to make a simple, bland-looking film to help with the light touch of the comedy, but however he got there, the film is lacking in especially striking visual moments. This was the only time Martin Bodin shot a film directed by Bergman (though he shot Bergman's screenwriting debut, Torment), a rare example of a one-off cinematography collaboration for the director, and it's clear they weren't challenging each other; this is very straightforward, easy-to process visual storytelling, lit for even exposure, and largely free of the probing angles and interrogative close-ups that made Sawdust and Tinsel such a remarkable piece. This is an easier film to digest in all ways, basically.

It's also very shaggy and loose: the farcical plays Bergman is drawing from, and the cycle of '30s divorce comedies from America that sure feel like an influence, though I have no idea if he'd seen them, are all models of tight construction, and A Lesson in Love is definitely not tight. The flashbacks are pressed into the film rather casually, and allowed to wander around and find their shape; if the idea is that a good marriage is all about the unforced flow of feelings, I guess I can understand why having such a lanky structure fits, but we know from To Joy and Summer Interlude that Bergman knew how to fit languid moments of shaggy intimacy into a well-built framework, and it would hardly hurt this film's comic priorities to feel a bit more propulsive and focused.

Also, I really just despise the last 20 seconds, a cloying little touch that has nothing to do with the film we've just watched.

Still and all, the film is awfully pleasurable. It's clear that Bergman had to work at doing comedy, and didn't always trust himself, but the end result has enough moments that can float by entirely on Dahlbeck and Björnstrand's excellent screen presence and ability to blend serious character work and bubble-light comedy, that it still feels like a pretty sturdy piece. Sturdy enough to kick off a short wave of Bergman-directed comedies, and while I would never trade all the crushing masterpieces we got after that wave ended for a career full of films just like this, I'm rather happy we got at least a couple.

On the cinematic side of things, that rebirth was signified by A Lesson in Love, Bergman's sole film released in 1954. In broad strokes (and specific details, as well), it's pretty much exactly what one would expect this writer - and more to the point, this writer with this taste in plays - to make as his first unabashedly funny project: an elegant sex comedy, gamely poking fun at the institution of marriage and the troubles people cause themselves through ego. The ego in this case largely belongs to David Erneman (Gunnar Björnstrand), a gynecologist who starts the film by calling off his current affair with the younger Susanne (Yvonne Lombard). Later, he gets on a train to Copenhagen, sharing a compartment with a man we don't need to worry about (Helge Hagerman), and a woman named Marianne (Eva Dahlbeck), who seems both unusually receptive and unusually dismissive of David's clumsy attempts to flirt. We'll learn, in a little bit, that this is because Marianne is David's wife, sick of his bored, transparent philandering, and preparing to leave him to be with her own lover. The rest of the film covers one day and fifteen years, as the Ernemans spent the trip to Copenhagen reflecting on the shared history that has brought them to this point, as he attempts to win her back.

The chronologically untethered flashbacks that flesh out this history are both the most interesting aspect of A Lesson in Love, aesthetically speaking, and probably its most obvious liability. The film has essentially set itself a problem to solve, in the form of David: how do you introduce a protagonist by making him seem strongly unlikable, and then find a way to make us root for him as he tries to make amends to his wife, a woman who has every justification for hating him? The film pulls no punches: the first thing it does after the opening credits is to present Susanne staring directly into the camera, accusing David - that is, the viewer - of being an uncaring bastard. The camera spins around after a moment of this to reveal that she's been talking to David's back, and just like that, by the end of the first shot, we are aware that he is a standoffish prick with a dreadful attitude about women. This doesn't get softened anytime soon, either; the first achronological scene (not clearly flagged as such, either) finds David and the couple's teenage daughter, Nix (Harriet Andersson) chatting over lunch, and part of her irritable adolescent diatribe consists of confronting him with the fact that she and Marianne and everyone else knows his a prick; Björnstrand does a superb job of reacting to this, as both a "well, obviously" moment, and a tiny hint of surprise that he's not keeping it a secret.

And so back to the puzzle the film sets for us: how to make us want this marriage to survive? And we sense that it will, given the very opening: the credits are interrupted by the voice of Bergman himself, letting us know in advance that we're about to watch a comedy, on account of the fact that it ends happily; otherwise it would be a tragedy (an echo and inversion of the narrator telling us Crisis, eight years earlier was just a light drama, "almost a comedy"; it reiterates the feeling that A Lesson in Love is functioning as a second debut). There's a little bit of desperation here, sure - "I'm Ingmar Bergman, and I can too laugh" - but it's also priming us to take none of what follows all that very seriously, including David's most obnoxious qualities. The use of flashbacks to soften the present-day material do a lot as well, both by keeping us from spending too much time at once with the most toxic form of the marriage, as well as showcasing the excellent chemistry between Dahlbeck and Björnstrand.

The film would be quite unimaginable without them as leads; it was even designed specifically to bring them back, after they worked so well in the comic segment of Bergman's 1952 anthology film Waiting Women. The only production story Bergman ever really talked about was all about how much he needed them: he had been wrestling with one of the scenes, and could not figure out to save his life how to make it funny. He was ready to junk it when the actors nicely asked him to leave, and they'd figure it out; an hour later, they let him come back to set, ready to film the scene exactly as they'd blocked it, and it was perfect. The moral of the story, to Bergman, was that this was the moment that taught him to give himself over to the collaborative process, letting his actors find their characters and then show him how the movie needed to be fashioned around them, and this is a tremendously valuable lesson for the man who would thereafter become one of the greatest directors of actors to have learned. But it also tells us something about A Lesson in Love just by itself: the film lives and dies on the spectacular comic chemistry of its leads. The most important part of any successful romantic comedy, ultimately, is that we like watching the couple together, and I absolutely loved these two: their perfectly relaxed cadence with each other even in their most sniping moments really is very lovely, especially when the film thoughtfully contrasts it with an early scene in their relationship, to showcase how that cadence is the result of long-simmering familiarity.

They're also both excellent performances individually: Dahlbeck's, in particular, is a strong argument that she belongs in the conversation about Bergman's finest actresses, and this isn't even one of the best films they made together! A major reason she's generally overlooked, I am certain, is that of their five collaborations - seven if you count the ones he only wrote the screenplay for - only Smiles of a Summer Night is one of Bergman's Consensus Masterpieces; another, on full display here, is that she's not really even a little bit neurotic or tormented, but simply has an easygoing way of accepting what happens, processing it (generally with a tightening of her mouth that makes it look like she's literally chewing things over) and moving on. It's a very graceful, open, high-spirited performance, of a sort that feels like top-tier work by a major Hollywood star of the '30s or '40s, and one does not typically look to a Bergman film for grace. But I love what Dahlbeck is up to here, humanising David through her lingering, slightly melancholy affection for him, while also letting us see why she's sick of his bullshit and making Marianne such a fully-realised personality through her interaction with non-David characters that we get an absolutely full and complete sense of how she feels about herself and the world on days when she's not on the brink of divorcing her husband.

Dahlbeck's work - and Björnstrand's, though he's mostly just up to doing a very good version of pretty standard "pathetic male egotist has his ego punctured, to his self-conscious benefit" arc - gets to the most important thing that makes A Lesson in Love work: it still takes itself seriously as a marital drama, despite being a breezy, at times quite weightless comedy. And I should say that I was not expecting to find the film nearly as funny as I did - Bergman is no more known for being funny now than he was in 1954, and the one thing he made before this point that wasn't a heavy drama, his series of Bris Soap commercials, is more playful and delightful than "funny". The comic sequence from Waiting Women never got more than a mild nod of intellectual amusement from me. But there are gags in A Lesson in Love that worked perfectly for me: those that are surprising, those that are humorously inevitable, and those that are just plain dumb (there are two slapstick fistfights, echoing each other in an unforced way).

Still, when the film announces itself at the very start as a comedy for grown-ups, it means it: the Ernemans' marriage is defined with just as much sincerity as any relationship in any prior Bergman film, and the care with which it is developed through the film assumes that we hope to learn a little bit more about marriages in general than we did going in (the "lesson" isn't just the characters'). There are graceful pieces of filmmaking surrounding this, including near the end, a remarkable shift from a painfully extreme long shot to a much closer, intimate shot framed around the couple's bodies, at the exact moment they decide to reconcile, that does as much as any piece of acting to sell us on the fundamental stability of this relationship.

That being said, among the film's flaws, one of the biggest is that it's pretty flat, stylistically. I do not know if Bergman wanted to make a simple, bland-looking film to help with the light touch of the comedy, but however he got there, the film is lacking in especially striking visual moments. This was the only time Martin Bodin shot a film directed by Bergman (though he shot Bergman's screenwriting debut, Torment), a rare example of a one-off cinematography collaboration for the director, and it's clear they weren't challenging each other; this is very straightforward, easy-to process visual storytelling, lit for even exposure, and largely free of the probing angles and interrogative close-ups that made Sawdust and Tinsel such a remarkable piece. This is an easier film to digest in all ways, basically.

It's also very shaggy and loose: the farcical plays Bergman is drawing from, and the cycle of '30s divorce comedies from America that sure feel like an influence, though I have no idea if he'd seen them, are all models of tight construction, and A Lesson in Love is definitely not tight. The flashbacks are pressed into the film rather casually, and allowed to wander around and find their shape; if the idea is that a good marriage is all about the unforced flow of feelings, I guess I can understand why having such a lanky structure fits, but we know from To Joy and Summer Interlude that Bergman knew how to fit languid moments of shaggy intimacy into a well-built framework, and it would hardly hurt this film's comic priorities to feel a bit more propulsive and focused.

Also, I really just despise the last 20 seconds, a cloying little touch that has nothing to do with the film we've just watched.

Still and all, the film is awfully pleasurable. It's clear that Bergman had to work at doing comedy, and didn't always trust himself, but the end result has enough moments that can float by entirely on Dahlbeck and Björnstrand's excellent screen presence and ability to blend serious character work and bubble-light comedy, that it still feels like a pretty sturdy piece. Sturdy enough to kick off a short wave of Bergman-directed comedies, and while I would never trade all the crushing masterpieces we got after that wave ended for a career full of films just like this, I'm rather happy we got at least a couple.

Categories: comedies, domestic dramas, ingmar bergman, love stories, romcoms, scandinavian cinema