Summer lovin' happened so fast

Summer Interlude was the first film directed by Ingmar Bergman that he was entirely happy to have made. That's enough to grab my attention, at least, and while there's no reason we have to agree with him (filmmakers have been getting their own films wrong since the beginning), it's still worth pondering what about the film made it "click" for him in a way that his earlier films didn't. Also, as it so happens, I do agree with him: this is the best film he'd made up to this point, now ten features into his career. Because sometimes, filmmakers actually can tell what the hell they're up to.

The film is drawn from life: Bergman was inspired by a romantic interlude from his own adolescence and the mingled feelings of nostalgia and regret it inspired. That interlude let to a short story titled "Mari", which, years later, he and Herbert Grevenius converted into a screenplay in early 1950, at a point in time where the director's life was in free-fall, and nostalgia mixed with regret must have felt especially sharp. His second marriage to Ellen Lundström, which had resulted in four children, was in the final stages of disintegrating, owing largely to his affair with Gun Grut, whom he'd marry in 1951. In 1949, he'd lost his position as director of the Gothenburg City Theatre, his main source of income, and a primary artistic channel. Funneling all of that into a story of a romantically frustrated performer convinced that her artistic career was on its last legs, haunted by the memory of a lovely past that represents a different path through life, must have been cathartic; at any rate, the end result is rich with pensive emotions and a pervasive sense of unarticulated regret. It is the very best kind of highly personal art, one that transmutes the specifics of Bergman's own feelings of despair into a new setting that makes those feelings more universal and elemental, without going so far as to tip into vague mush.

I emphasise all of this up front because it's easy to hear the title and attend to the bulk of the plot and conclude that this is a lovely, warm, wistful tribute to first love and the awakening of romance and sexual desire. It is that, but filtered and diluted through ambivalence and pain; it's romantic teen melodrama, sure, but one viewed through a glass darkly, if you'll permit me to say so* The film begins and ends not during the warmth of summer but during the chill winds of autumn (actually played by the springtime, and you can tell if you look too closely at the bare limbs of trees that are starting to show buds). And it's not just a framework; there's enough material in this mode, with enough consequential narrative material, that it always feels like that's where the story really resides, and that the happy, intoxicating flashback is just that, a flashback - a long one that takes up a considerable majority of the film's running time, but still something place apart from us, while the "present day" material is much more tangible and active.

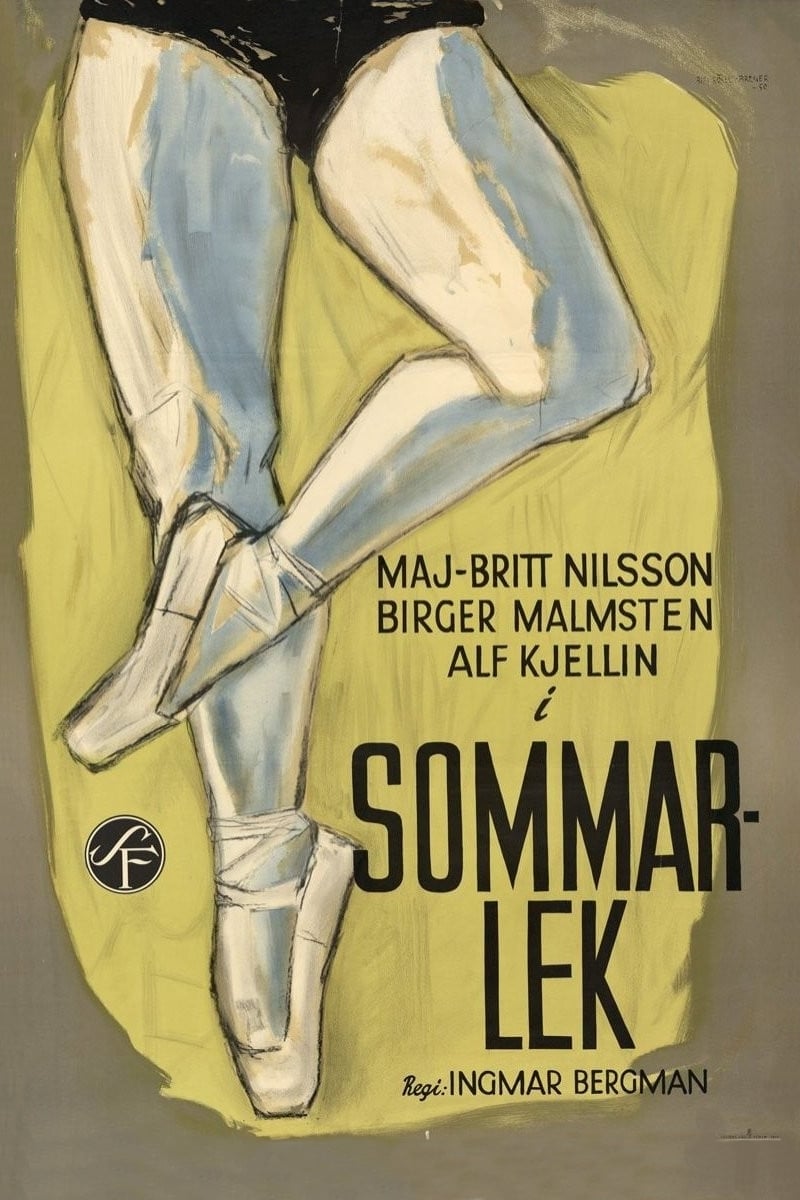

The film is focused on 28-year-old ballerina Marie (Maj-Britt Nilsson), currently rehearsing the role of Odette in Swan Lake; as egged on by her 28-year-old colleague Kaj (Annalisa Ericson), she is at the moment obsessed with the knowledge that she's rapidly approaching retirement. This particular day seems accursed; before dress rehearsal starts, various figures around the theater have been musing that something feels wrong, and Marie received an unmarked package in the mail, with a diary inside of it; opening the first page caused her to have a clearly disturbing vision of a young man (Birger Malmsten), and she's plainly unready to start dancing. Luckily, or not, just as she takes to the stage, the lights blow out for no immediately apparent reason, with announcement that it will take all day to fix. Now with several hours to kill, and her current boyfriend David (Alf Kjellin) too busy with his newspaper job, Marie reluctantly hops on a ferry out to some of the islands of the Stockholm Archipelago. On one of these islands, she heads straight to tiny one-room cottage, and as she sits in the spare room she drifts back 13 years, to a summer vacation that started in the same cottage, and involved a head-over-heels love affair with that young man whose face she saw, Henrik.

Most of Summer Interlude takes place 13 years in the past, and watches as Marie and Henrik grow increasingly intoxicated with each other's presence, but there's no escaping knowledge that we are viewing these events from a Marie who's almost twice as old and clearly convinced that her life is awful (she's sunk everything into dance, which has repaid her by breaking her body and forcing her into retirement before age 30), and perhaps has never truly felt happiness since that summer. The film takes its time to set up that frame, and it presents the flashback as the resolution to the mystery of why Marie is closed-off and alone - we don't know for quite a long time why exactly Marie and Henrik never saw each other again, but it's very obvious that this is the case, and it's also pretty obvious that Marie didn't make that choice of her own free will. It throws some voiceover narration our way, less to clarify things, I suspect (the visual storytelling is quite clear), and more to keep reminding us of Old Marie, haunted by these ghosts. In honesty, the voiceover is one of the film's bigger flaws; it's not motivated by anything (we know that she's "seeing" these memories, not telling them to anybody), and comes across as a blatant screenwriting device. Still, it gets the job done.

The flipside to this: let me not suggest that Summer Interlude is a joyless slog. On the contrary, what moved no less than Jean-Luc Godard to declare in 1958 that it was one of the most beautiful films ever made is its pervasive summery warmth, its depiction of the excitement and unhesitating enthusiasm of teen romance with light, shimmering imagery and a pair of wonderfully airy performances by the leads. Admittedly, their casting, physically speaking, is one of the biggest problems here: 25-year-old Nilsson and 29-year-old Malmsten are both unconvincing teenagers, especially given the combination of bright, direct light and close-ups that give us ample opportunity to notice the encroaching lines around their eyes and mouths. And this is not an incidental issue for a film that is extremely invested in the fresh innocence of adolescence, particularly given that the contrast between Marie's appearance as a youth and as an adult is a recurring visual motif. But both actors do great things to compensate for this, Nilsson especially. Her performance is fully of gawky, teenage physicality, from the first time we see her as a teen and she's clomping around the little cottage swinging her limbs wide and keeping in constant, restless movement. Later, in a scene where she and Malmsten are sitting across from each other on a rock, the camera stares at her back as she unselfconsciously contorts her arms, trying to get at an itchy spot on her back. It's a tiny moment that is, somehow, my favorite character beat in any Bergman film to this point: there's a crude, vulgar realism to it (people don't get itchy in movies!), which is translated in Nilsson's open, organic physicality into a wonderfully free expression of unfussy, embodied presence. Her whole performance is pitched at that level, or its negative mirror when she makes a mask of her face as a hard, emotionally constipated adult (literally, given the make-up she's wearing to play the swan).

Nilsson's performance suggests a strong new fusion of cinema with the realist theatrical traditions Bergman loved so well, but Summer Interlude also makes great use of film form more specifically. Gunnar Fischer's cinematography is basically the next most important character after Marie, capturing the twilight glow of a Scandinavian summer night and the crisp, unfiltered hard sun of a summer day with a luminous range of greys that feels imported directly from the poetic realism of French cinema in the '30s, but applied to a more severe psychological and physical realism than those films tended to involve. In the present-day scenes, he shifts more towards harder contrasts, particular inside the ballet theater, framed with Langian attention to geometry and freaky noir-esque shadows. There's a late conversation with the ballet master (Stig Olin, in his last film with Bergman) presenting a philosophic vision about the bitterness and beauty of life as an artist, presented entirely as angular frames-within-frames and complicated mirror set-ups that goes into something downright Expressionist, in creating a somewhat overbearing visual metaphor for Marie's sadness.

This is also the first Bergman film that seems to have a very strong grasp on how editing can shape and define our experience of a movie, rather than simply using it to piece shots together: this was no less than the fifth of Bergman's films cut by Oscar Rosander, but something clicks her that hadn't before. It is, admittedly, not always possible to tell whether what we're seeing is an exciting strategy or mere sloppiness involving the 180-degree line, but there's something startling about the way that the cutting obscures Marie's position when she's feeling locked out of a conversation with Henrik's awful aunt (Mimi Pollak), or to create a sense of uneasy incoherence in the theater at the start of the very terrible way. Much more of the editing is smaller and simpler, as when it creates a contrast between Henrik's diary and an aggressive shot of half of Marie's face, the first time Bergman uses this kind of fragmentary close-up that will become one of his signature. Sometimes, it's just interrupting a wide shot with a medium shot to keep us focused on the scene's POV, or even the most important thing of all, letting long takes move at their own pace, generally to allow us to feel the weight of Nilssson and Malmsten's physical presence.

All in all, a remarkable, confident breakthrough: it in some way repeats the ideas of To Joy, including that film's focus on how the performing arts create room for the artist to cope with personal trauma, though Summer Interlude's final shots keep the focus inward, rather than To Joy's unexpected and extraordinary final moment of turning the focus outward and to the audience; it is still a bold and challenging final shot, though not nearly as expansive and unsettling. Still, in almost every other way, this film is the better version of the material, freer and with a much tighter control of a wider range of shifting emotions. It's not flawless; the subplot about Marie's predatory uncle Erland (George Funkquist) is more sour than illuminating, and the film suggests that Bergman's unproductive infatuation with double-exposures is still going strong. Still, it's a lovely study of love and loss and moving forward, controlled but not not authoritarian in how it guides us into the story and how the actors inhabit their characters. With benefit of hindsight, this is the first time that a Bergman film feels entirely like a "Bergman film". There are still kinks to work out - the dreadful This Can't Happen Here was shot after this, though it was released later, so we can't say that Bergman had definitely settled on his artistic identity yet - but the confidence of imagination and execution demonstrated in Summer Interlude make it easy, for the first time, to believe that this filmmaker had medium-defining masterpieces in his future.

*It would be probably be better if you didn't permit me to say so.

The film is drawn from life: Bergman was inspired by a romantic interlude from his own adolescence and the mingled feelings of nostalgia and regret it inspired. That interlude let to a short story titled "Mari", which, years later, he and Herbert Grevenius converted into a screenplay in early 1950, at a point in time where the director's life was in free-fall, and nostalgia mixed with regret must have felt especially sharp. His second marriage to Ellen Lundström, which had resulted in four children, was in the final stages of disintegrating, owing largely to his affair with Gun Grut, whom he'd marry in 1951. In 1949, he'd lost his position as director of the Gothenburg City Theatre, his main source of income, and a primary artistic channel. Funneling all of that into a story of a romantically frustrated performer convinced that her artistic career was on its last legs, haunted by the memory of a lovely past that represents a different path through life, must have been cathartic; at any rate, the end result is rich with pensive emotions and a pervasive sense of unarticulated regret. It is the very best kind of highly personal art, one that transmutes the specifics of Bergman's own feelings of despair into a new setting that makes those feelings more universal and elemental, without going so far as to tip into vague mush.

I emphasise all of this up front because it's easy to hear the title and attend to the bulk of the plot and conclude that this is a lovely, warm, wistful tribute to first love and the awakening of romance and sexual desire. It is that, but filtered and diluted through ambivalence and pain; it's romantic teen melodrama, sure, but one viewed through a glass darkly, if you'll permit me to say so* The film begins and ends not during the warmth of summer but during the chill winds of autumn (actually played by the springtime, and you can tell if you look too closely at the bare limbs of trees that are starting to show buds). And it's not just a framework; there's enough material in this mode, with enough consequential narrative material, that it always feels like that's where the story really resides, and that the happy, intoxicating flashback is just that, a flashback - a long one that takes up a considerable majority of the film's running time, but still something place apart from us, while the "present day" material is much more tangible and active.

The film is focused on 28-year-old ballerina Marie (Maj-Britt Nilsson), currently rehearsing the role of Odette in Swan Lake; as egged on by her 28-year-old colleague Kaj (Annalisa Ericson), she is at the moment obsessed with the knowledge that she's rapidly approaching retirement. This particular day seems accursed; before dress rehearsal starts, various figures around the theater have been musing that something feels wrong, and Marie received an unmarked package in the mail, with a diary inside of it; opening the first page caused her to have a clearly disturbing vision of a young man (Birger Malmsten), and she's plainly unready to start dancing. Luckily, or not, just as she takes to the stage, the lights blow out for no immediately apparent reason, with announcement that it will take all day to fix. Now with several hours to kill, and her current boyfriend David (Alf Kjellin) too busy with his newspaper job, Marie reluctantly hops on a ferry out to some of the islands of the Stockholm Archipelago. On one of these islands, she heads straight to tiny one-room cottage, and as she sits in the spare room she drifts back 13 years, to a summer vacation that started in the same cottage, and involved a head-over-heels love affair with that young man whose face she saw, Henrik.

Most of Summer Interlude takes place 13 years in the past, and watches as Marie and Henrik grow increasingly intoxicated with each other's presence, but there's no escaping knowledge that we are viewing these events from a Marie who's almost twice as old and clearly convinced that her life is awful (she's sunk everything into dance, which has repaid her by breaking her body and forcing her into retirement before age 30), and perhaps has never truly felt happiness since that summer. The film takes its time to set up that frame, and it presents the flashback as the resolution to the mystery of why Marie is closed-off and alone - we don't know for quite a long time why exactly Marie and Henrik never saw each other again, but it's very obvious that this is the case, and it's also pretty obvious that Marie didn't make that choice of her own free will. It throws some voiceover narration our way, less to clarify things, I suspect (the visual storytelling is quite clear), and more to keep reminding us of Old Marie, haunted by these ghosts. In honesty, the voiceover is one of the film's bigger flaws; it's not motivated by anything (we know that she's "seeing" these memories, not telling them to anybody), and comes across as a blatant screenwriting device. Still, it gets the job done.

The flipside to this: let me not suggest that Summer Interlude is a joyless slog. On the contrary, what moved no less than Jean-Luc Godard to declare in 1958 that it was one of the most beautiful films ever made is its pervasive summery warmth, its depiction of the excitement and unhesitating enthusiasm of teen romance with light, shimmering imagery and a pair of wonderfully airy performances by the leads. Admittedly, their casting, physically speaking, is one of the biggest problems here: 25-year-old Nilsson and 29-year-old Malmsten are both unconvincing teenagers, especially given the combination of bright, direct light and close-ups that give us ample opportunity to notice the encroaching lines around their eyes and mouths. And this is not an incidental issue for a film that is extremely invested in the fresh innocence of adolescence, particularly given that the contrast between Marie's appearance as a youth and as an adult is a recurring visual motif. But both actors do great things to compensate for this, Nilsson especially. Her performance is fully of gawky, teenage physicality, from the first time we see her as a teen and she's clomping around the little cottage swinging her limbs wide and keeping in constant, restless movement. Later, in a scene where she and Malmsten are sitting across from each other on a rock, the camera stares at her back as she unselfconsciously contorts her arms, trying to get at an itchy spot on her back. It's a tiny moment that is, somehow, my favorite character beat in any Bergman film to this point: there's a crude, vulgar realism to it (people don't get itchy in movies!), which is translated in Nilsson's open, organic physicality into a wonderfully free expression of unfussy, embodied presence. Her whole performance is pitched at that level, or its negative mirror when she makes a mask of her face as a hard, emotionally constipated adult (literally, given the make-up she's wearing to play the swan).

Nilsson's performance suggests a strong new fusion of cinema with the realist theatrical traditions Bergman loved so well, but Summer Interlude also makes great use of film form more specifically. Gunnar Fischer's cinematography is basically the next most important character after Marie, capturing the twilight glow of a Scandinavian summer night and the crisp, unfiltered hard sun of a summer day with a luminous range of greys that feels imported directly from the poetic realism of French cinema in the '30s, but applied to a more severe psychological and physical realism than those films tended to involve. In the present-day scenes, he shifts more towards harder contrasts, particular inside the ballet theater, framed with Langian attention to geometry and freaky noir-esque shadows. There's a late conversation with the ballet master (Stig Olin, in his last film with Bergman) presenting a philosophic vision about the bitterness and beauty of life as an artist, presented entirely as angular frames-within-frames and complicated mirror set-ups that goes into something downright Expressionist, in creating a somewhat overbearing visual metaphor for Marie's sadness.

This is also the first Bergman film that seems to have a very strong grasp on how editing can shape and define our experience of a movie, rather than simply using it to piece shots together: this was no less than the fifth of Bergman's films cut by Oscar Rosander, but something clicks her that hadn't before. It is, admittedly, not always possible to tell whether what we're seeing is an exciting strategy or mere sloppiness involving the 180-degree line, but there's something startling about the way that the cutting obscures Marie's position when she's feeling locked out of a conversation with Henrik's awful aunt (Mimi Pollak), or to create a sense of uneasy incoherence in the theater at the start of the very terrible way. Much more of the editing is smaller and simpler, as when it creates a contrast between Henrik's diary and an aggressive shot of half of Marie's face, the first time Bergman uses this kind of fragmentary close-up that will become one of his signature. Sometimes, it's just interrupting a wide shot with a medium shot to keep us focused on the scene's POV, or even the most important thing of all, letting long takes move at their own pace, generally to allow us to feel the weight of Nilssson and Malmsten's physical presence.

All in all, a remarkable, confident breakthrough: it in some way repeats the ideas of To Joy, including that film's focus on how the performing arts create room for the artist to cope with personal trauma, though Summer Interlude's final shots keep the focus inward, rather than To Joy's unexpected and extraordinary final moment of turning the focus outward and to the audience; it is still a bold and challenging final shot, though not nearly as expansive and unsettling. Still, in almost every other way, this film is the better version of the material, freer and with a much tighter control of a wider range of shifting emotions. It's not flawless; the subplot about Marie's predatory uncle Erland (George Funkquist) is more sour than illuminating, and the film suggests that Bergman's unproductive infatuation with double-exposures is still going strong. Still, it's a lovely study of love and loss and moving forward, controlled but not not authoritarian in how it guides us into the story and how the actors inhabit their characters. With benefit of hindsight, this is the first time that a Bergman film feels entirely like a "Bergman film". There are still kinks to work out - the dreadful This Can't Happen Here was shot after this, though it was released later, so we can't say that Bergman had definitely settled on his artistic identity yet - but the confidence of imagination and execution demonstrated in Summer Interlude make it easy, for the first time, to believe that this filmmaker had medium-defining masterpieces in his future.

*It would be probably be better if you didn't permit me to say so.