The amazing race

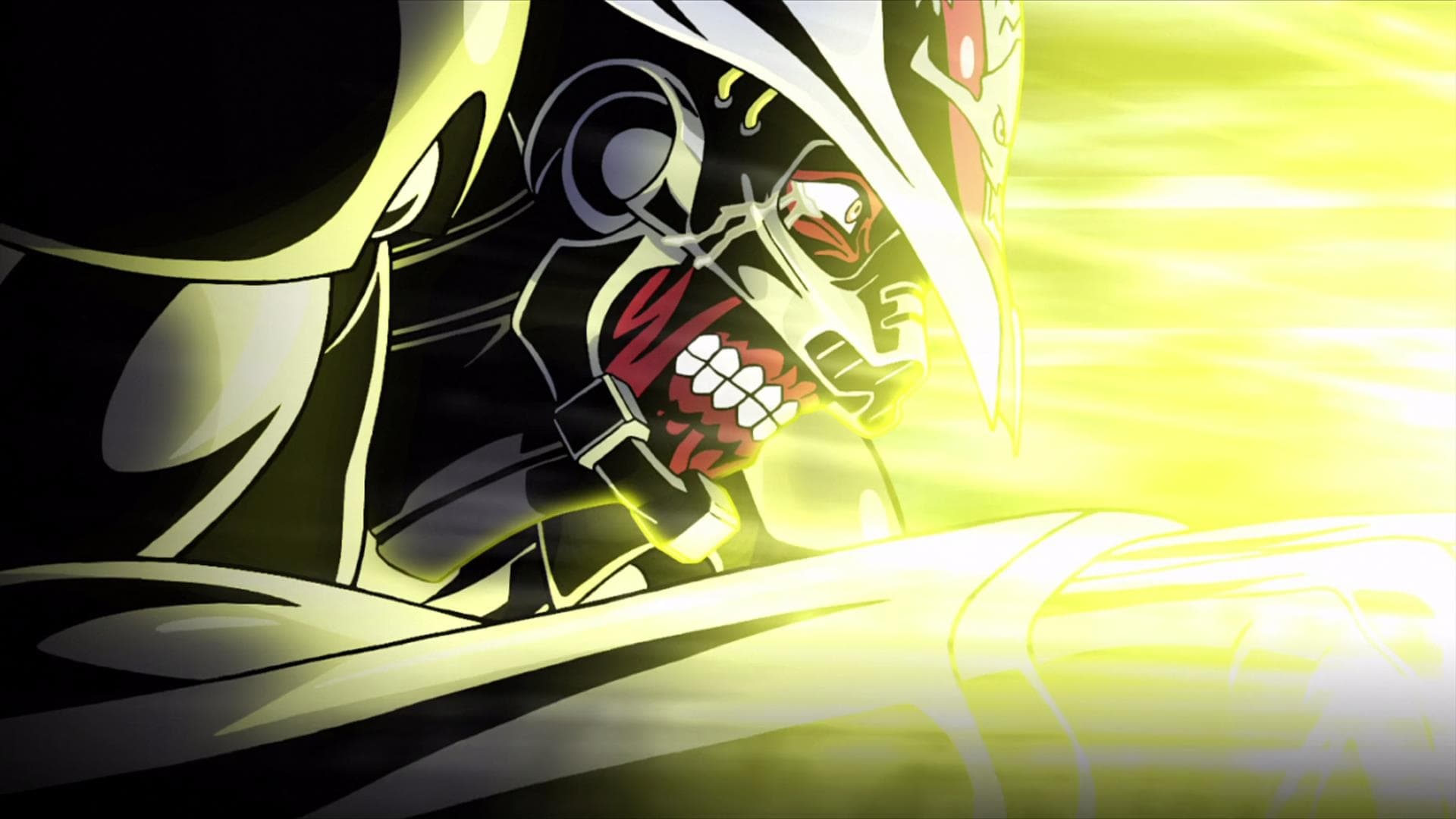

Hyperbole is a dangerous thing, but even so, Redline is one of the most striking-looking animated movies I have ever seen. The film's style feels like it should be easier to pin down than it is; there's a clear indebtedness to '60s pop art and '90s and '00s digitally-colored comics in the bold swatches of strong colors, and the deep, solid blacks that define the shapes of faces and spaces. If Roy Lichtenstein designed the covers for Amazing Stories, using computer painting style and the character design ethos of Japanese animation, and the whole thing was in constant movement, that's getting us pretty close to the vibe of the thing. Though even throwing around a term like "pop art" doesn't at all get at how strongly the hyper-saturated colors seem to glow off the screen. This is as good an example as I can name of the productive and healthy relationship between different animation techniques: every frame was hand-drawn (around 100,000 drawings in total, according to the press releases at the time, a substantial number for a 102-minute animated feature), and so we get the fluidity and flexibility of traditional animation, but it has a sleek, futuristic cleanliness that could only have been achieved by using the stability of computer painting.

There's an exceedingly short list of films that combine these techniques in such a bravura way that I'd be ready to compare this to: The Tale of the Princess Kaguya, The Red Turtle, The Girl Without Hands, Lu Over the Wall. Every one of those is newer than Redline, and to a certain extent, every one of them is "tamer". With Redline, the startling mix of color, flatness, and fluid movement - I don't want to harp on it, but this is extraordinarily smooth for Japanese animation, especially in the effects-heavy sequences (and this is a film with a lot of effects) - is all in service to creating something wild and excessive, a movie that isn't merely going over the edge, but wants us to be constantly aware of how far out we're dangling. It is overwhelming in every way a film can be visually and sonically overwhelming. It's not just that it's brightly colored and fast-moving, but that the fast movement keeps bringing new colors in, constantly demanding our eyes re-adjust to new stimuli and never giving them enough time to actually do so.

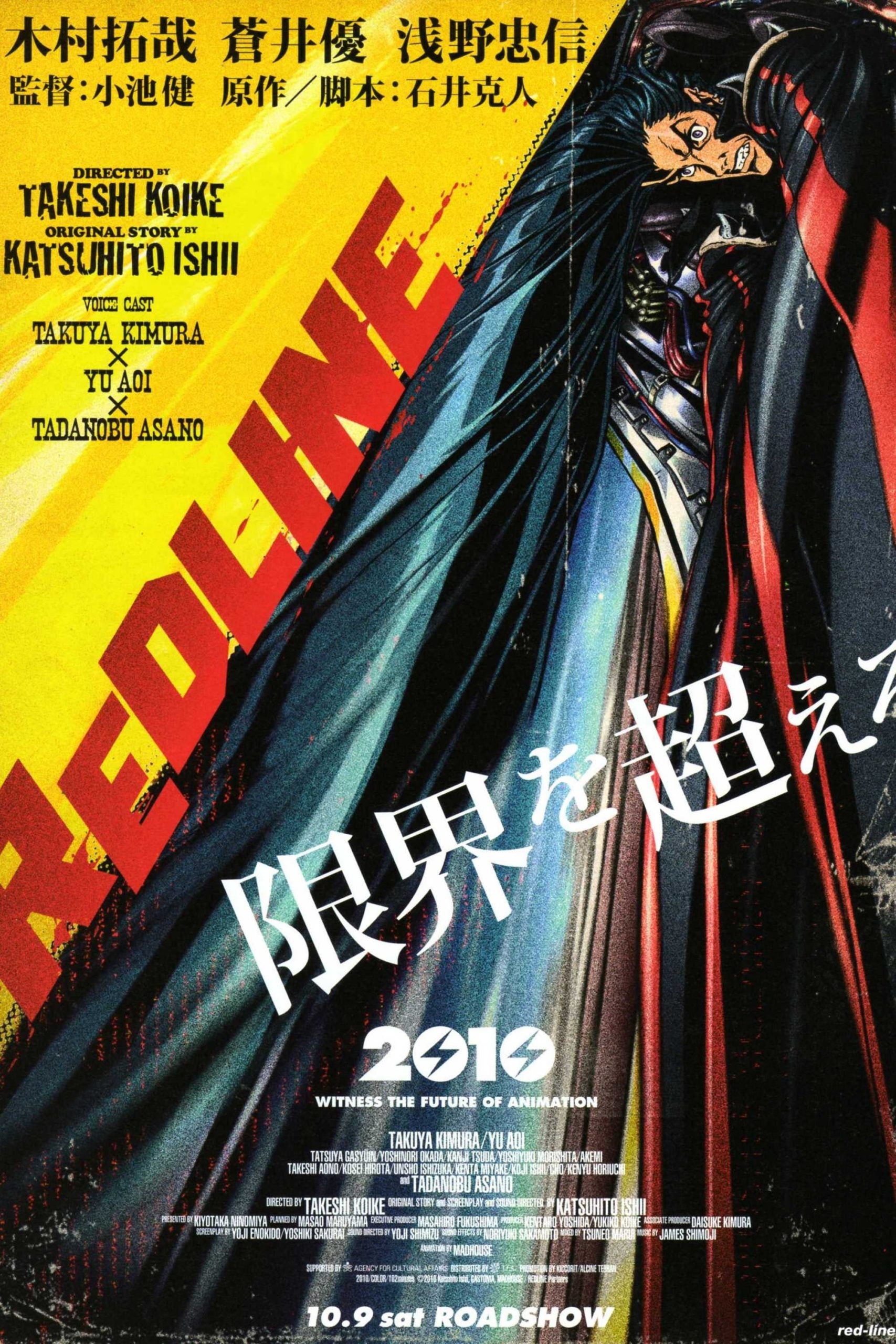

All of this is in service to a story about the distant future, in which a galaxy-spanning race network is holding its every-five-years championship race, the Redline. The competitors are a wide array of humans and aliens, the vehicles range from hovercraft that transform into dancing robots all the way to our protagonist, driving a gold-colored Trans Am, and the race sequences take full advantage of the different kinds of movement that all this can permit, laid atop an alien robot planet full of desolate grey plains and shiny dark metallic surfaces. It's an environment and a scenario perfectly designed to take advantage of animation, and director Koike Takeshi - making his feature debut, after an admirable career as an animator, as well as directing the pilot for Afro Samurai and a sequence in The Animatrix - goes all-in on letting his drivers fly around space in flagrantly impossible ways, while leaping from close-ups to wide shots and back with abandon, but always preserving the sense that every part of the frame is in constant motion. Alongside this, there's a thrumming techno score by James Shimoji that insistently, loudly pushes all of the racing sequences ahead with a constant rhythmic throb.

The film does a phenomenal job of marshaling all its techniques towards this sense of constant movement, enough so that even during the dialogue scenes, things are being kept moving. For example, our introduction to several of the racers comes in the form of packages that draw equally from sports television and the loud tinny ballyhoo of a fighting game in a crowded arcade. Even in the most straightforward conversation scenes, there are enough clashing colors and enough different ways of moving the non-human characters that there's literally not one single scene that simple shows two people talking in a static composition - even when all else fails, the film indulges in distorting the poses and movements of characters using squash and stretch techniques to mimic the fish-eye effect of a wide-angle lens.

It would all seem desperate to keep our attention at any cost, but there's absolutely no trace of desperation, only proud creativity. I suppose it's at least possible to ding the film for packing all of this stylistic excess onto a largely generic, insubstantial story: it's about JP (Kimura Takuya), a scoundrel and rogue of a racer, who ends up lucking his way into Redline, flirting with the ambitious driver Sonoshee (Aoi Yu), and trying to win a race in the face of the angry cyborgs who live on the planet, are extremely unhappy that Redline is taking place there, and have accordingly decided to wage war on the racers using both their automated systems and, ultimately, a kind of mutant embodiment of nuclear energy taking the form of a baby that screams lasers. So even in a plot synopsis, it's hard to keep the focus just on JP and his crew (including his mobbed-up mechanic, the Yoda-esque Frisbee (Asano Tadanobu) and the multi-limbed junkman Old Man Mole (Aono Takeshi); there's too much wild, excessive pulp sci-fi world-building swirling all around the "story". This is an unusually clear case of a film that's using its story to pave the way for its imagery and the exciting momentum that they generate: even the ending is handled as more of an ironic joke than a sincere wrap-up to character arcs that aren't really sincere in any way. They're just there.

Which isn't to say that we don't care about the characters; we just don't necessarily care about them because of script reasons. Koike and his animators do great work in creating personalities for these characters purely through design and draftsmanship: JP's giant '50s-style pompadour, Frisbee's nonchalant slouching, or the vivid, distinctly different ways that all of the side characters move in racing and dialogue scenes alike. This is, after all, what animation is good for: creating strong characterisations through drawings and the illusion of movement. In Redline, all these bizarre aliens and even more bizarre humans are so immediately "readable" that their emotional journeys become pleasurable to watch even despite a boilerplate story whose beats are clear from the moment we understand that we're watching a race movie. The film's goals lie elsewhere than surprising us with a narrative; it wants to surprise us with the bright depth of its world, its sense of transporting us to a completely different universe of sunshiny colors and film noir lighting and aliens whose appealing looks are offset by their strange movement. It never lets up, but it's too creative and varied to ever feel exhausting; instead, it feels like being taken on a tour by a particularly enthusiastic, chipper guide, who is always even more excited by the next thing than he was by this thing. It's not just that it's boundlessly creative; it's also one of the most enthusiastic and enjoyable animated films of the 21st Century, always presenting us with new spectacle and always keeping it attached to the subjective experience of a well-defined, if ultimately clichéd set of everyday protagonists.

There's an exceedingly short list of films that combine these techniques in such a bravura way that I'd be ready to compare this to: The Tale of the Princess Kaguya, The Red Turtle, The Girl Without Hands, Lu Over the Wall. Every one of those is newer than Redline, and to a certain extent, every one of them is "tamer". With Redline, the startling mix of color, flatness, and fluid movement - I don't want to harp on it, but this is extraordinarily smooth for Japanese animation, especially in the effects-heavy sequences (and this is a film with a lot of effects) - is all in service to creating something wild and excessive, a movie that isn't merely going over the edge, but wants us to be constantly aware of how far out we're dangling. It is overwhelming in every way a film can be visually and sonically overwhelming. It's not just that it's brightly colored and fast-moving, but that the fast movement keeps bringing new colors in, constantly demanding our eyes re-adjust to new stimuli and never giving them enough time to actually do so.

All of this is in service to a story about the distant future, in which a galaxy-spanning race network is holding its every-five-years championship race, the Redline. The competitors are a wide array of humans and aliens, the vehicles range from hovercraft that transform into dancing robots all the way to our protagonist, driving a gold-colored Trans Am, and the race sequences take full advantage of the different kinds of movement that all this can permit, laid atop an alien robot planet full of desolate grey plains and shiny dark metallic surfaces. It's an environment and a scenario perfectly designed to take advantage of animation, and director Koike Takeshi - making his feature debut, after an admirable career as an animator, as well as directing the pilot for Afro Samurai and a sequence in The Animatrix - goes all-in on letting his drivers fly around space in flagrantly impossible ways, while leaping from close-ups to wide shots and back with abandon, but always preserving the sense that every part of the frame is in constant motion. Alongside this, there's a thrumming techno score by James Shimoji that insistently, loudly pushes all of the racing sequences ahead with a constant rhythmic throb.

The film does a phenomenal job of marshaling all its techniques towards this sense of constant movement, enough so that even during the dialogue scenes, things are being kept moving. For example, our introduction to several of the racers comes in the form of packages that draw equally from sports television and the loud tinny ballyhoo of a fighting game in a crowded arcade. Even in the most straightforward conversation scenes, there are enough clashing colors and enough different ways of moving the non-human characters that there's literally not one single scene that simple shows two people talking in a static composition - even when all else fails, the film indulges in distorting the poses and movements of characters using squash and stretch techniques to mimic the fish-eye effect of a wide-angle lens.

It would all seem desperate to keep our attention at any cost, but there's absolutely no trace of desperation, only proud creativity. I suppose it's at least possible to ding the film for packing all of this stylistic excess onto a largely generic, insubstantial story: it's about JP (Kimura Takuya), a scoundrel and rogue of a racer, who ends up lucking his way into Redline, flirting with the ambitious driver Sonoshee (Aoi Yu), and trying to win a race in the face of the angry cyborgs who live on the planet, are extremely unhappy that Redline is taking place there, and have accordingly decided to wage war on the racers using both their automated systems and, ultimately, a kind of mutant embodiment of nuclear energy taking the form of a baby that screams lasers. So even in a plot synopsis, it's hard to keep the focus just on JP and his crew (including his mobbed-up mechanic, the Yoda-esque Frisbee (Asano Tadanobu) and the multi-limbed junkman Old Man Mole (Aono Takeshi); there's too much wild, excessive pulp sci-fi world-building swirling all around the "story". This is an unusually clear case of a film that's using its story to pave the way for its imagery and the exciting momentum that they generate: even the ending is handled as more of an ironic joke than a sincere wrap-up to character arcs that aren't really sincere in any way. They're just there.

Which isn't to say that we don't care about the characters; we just don't necessarily care about them because of script reasons. Koike and his animators do great work in creating personalities for these characters purely through design and draftsmanship: JP's giant '50s-style pompadour, Frisbee's nonchalant slouching, or the vivid, distinctly different ways that all of the side characters move in racing and dialogue scenes alike. This is, after all, what animation is good for: creating strong characterisations through drawings and the illusion of movement. In Redline, all these bizarre aliens and even more bizarre humans are so immediately "readable" that their emotional journeys become pleasurable to watch even despite a boilerplate story whose beats are clear from the moment we understand that we're watching a race movie. The film's goals lie elsewhere than surprising us with a narrative; it wants to surprise us with the bright depth of its world, its sense of transporting us to a completely different universe of sunshiny colors and film noir lighting and aliens whose appealing looks are offset by their strange movement. It never lets up, but it's too creative and varied to ever feel exhausting; instead, it feels like being taken on a tour by a particularly enthusiastic, chipper guide, who is always even more excited by the next thing than he was by this thing. It's not just that it's boundlessly creative; it's also one of the most enthusiastic and enjoyable animated films of the 21st Century, always presenting us with new spectacle and always keeping it attached to the subjective experience of a well-defined, if ultimately clichéd set of everyday protagonists.

Categories: action, animation, japanese cinema, science fiction