Defector? I hardly know 'or!

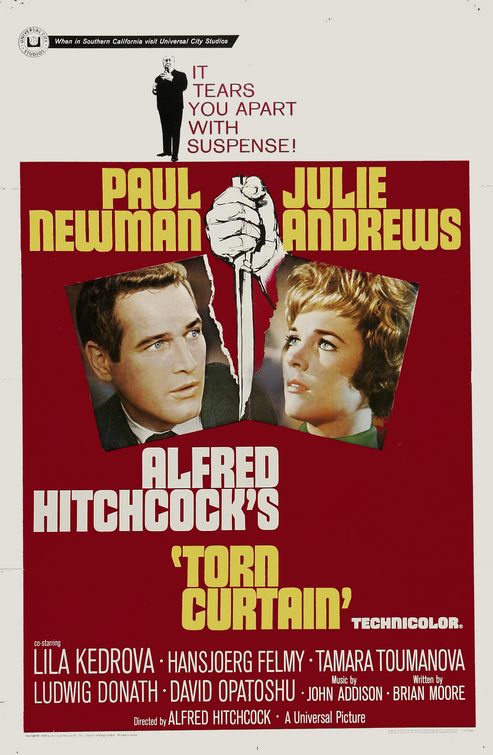

The book-length interview Hitchcock/Truffaut (one of the greatest texts about how filmmakers make films that you will ever read), was first published in 1966, at which point Alfred Hitchcock's newest film was Torn Curtain, from that summer. He didn't have very much to say about it to François Truffaut, skimming over a few sequences, point out one that did what he wanted it to, and grousing that Paul Newman was a disappointing leading man. In the revised version of the book published in 1983, after Hitchcock's death, Truffaut offered more thoughts on the director's late films, including correspondence between the two of them in which Hitchcock was even more frank in his irritation with Torn Curtain, a film wherein he felt overridden by the studio at several points, most destructively in their insistence on casting Newman and Julie Andrews, who used up all the budget and forced a tight shooting schedule that he wasn't ready for. One gets the impression from Hitchcock/Truffaut that Hitchcock wasn't particularly excited about most of his post-The Birds films; one gets the further impression that Torn Curtain is the one he liked making the least.

It shows. This isn't the most detached that I've ever felt this director to be from his material - one doesn't get the sad aura of complete capitulation that we find from him 1939's Jamaica Inn, a joyless Charles Laughton period piece - but it's extremely clear that he didn't want to make this film, at least not the way he had to make it. There are a few good moments that would work as one of the lesser setpieces in one of his masterpieces, and a good handful of colorful side characters who sweep into the film with blast of personality, so he's not completely checked out. But given how strong the plot hook is - a plot hook that Hitchcock came up with himself, before sending it to screenwriter Brian Moore to make a script out of it - it's slightly agonising how much the plot drags, and how little is made out of the most promising angles on the story.

That story is an original spy thriller, inspired by a pair of British men who defected to the Communist East: more specifically, with the wife of one of those men, who packed up their children several weeks later and defected right after him. The question the film tackles: what must have been going through her mind while she did that? In this case, a whole lot of panicky mistrust. Professor Michael Armstrong (Newman), an American physicist, is traveling to a European conference with his fiancée and assistant (ah, the '60s!), Sarah Sherman (Andrews). He's already acting a little strange on the boat trip over, and he gets stranger still once they've arrived in Copenhagen; soon enough, she's managed to surreptitiously follow him enough that she's on a plane several rows behind him, traveling to East Berlin, very much against his wishes. Upon landing, she learns the horrible truth: he's defecting.

We then immediately switch over the Michael's perspective on events, to learn that he's doing no such thing. In fact, he's faking defection, in order to dig up some secrets that will help with his research on anti-missile technology for the U.S. government. This means he not only has to safely navigate East Germany without any formal training in espionage, he also has to deal with the destablising presence of Sarah, who has looked deep inside herself, and with great reluctance, committed herself to actually defecting, in order to stay with Michael. Eventually, all of this gets smoothed out, but it's taken enough effort, and there have been enough missteps along the way, that the reunited lovers are now obliged to engage in a delicate, complex hunt across a hostile country to escape the increasingly suspicious East German officials.

That's two different levels on which this really ought to work: the idea of mixing love with high-stakes espionage, and even implicitly finding that espionage adds a certain erotic spice to one's romantic partnership, is vintage Hitchcock stretching all the way back to The 39 Steps from 1935 (a film whose three-part structure is echoed here) and The Man Who Knew Too Much from 1934. Meanwhile, telling a story that switches character perspectives so dramatically as this one does when it hops from Sarah's shoulder to Michael's is a suitable experiment in feeding the audience information in a way that challenges and upsets our understanding of how movies work, a fine extension of similar games played in 1950's Stage Fright and 1958's Vertigo. Even so, the storytelling here is shapeless and slack. Especially in its third phase, Torn Curtain becomes nothing but a fetch quest, schlepping the characters from one location to another in scenes that hang together in the most brutally literal sense, but don't have the wonderful sense of events spilling over that marks the best of Hitch's earlier "crisscross a nation chasing clues" films, like The 39 Steps or 1959's North by Northwest. It just clicks methodically from scene to scene, and from supporting character to supporting character.

The big problem is that the film gives up on Michael and Sarah almost immediately. It seems like we're on good footing at the very start: the film's opening is very fussy and mannered in a way that feels exactly like a '30s elegant comedy, using a motif of name tags on lapels to introduce us to the shipful of traveling physicists before using it to show Michael and Sarah's clothed draped over the chair next to the bed where they're rolling around with each other. And how much of a joy it must have been to Hitchcock to get to show his very first (albeit entirely chaste) sex scene, which is perhaps why this scene feels so emotionally charged: he shows both lovers in extreme close-ups in romantic soft focus, capturing something of the playful eroticism of two people comfortable with each other's bodies. It's a great kick-off to a love story that immediately face-plants: there will never be another moment for the rest of Torn Curtain when Newman and Andrews have any particular chemistry at all. Neither actor is doing particularly good solo work, either: Newman's performance is charmless and brusque, one of the worst screen performances I've ever seen him give, while Andrews is merely bland an insubstantial.

That's basically the film, once it becomes clear how meager the leads are going to be. There are some moments that work mechanically, most famously a death scene that goes on and on for endless seconds, while the view cuts around to increasingly baroque angles on the action. It's the one moment Hitchcock owned to being happy with, his way of mocking the spy thrillers that had become a fixture of European and American cinema in the few years since James Bond made his first appearance, with their exciting lack of weight to human morality. I might add to that a bus sequence near the end makes good use of a variation between medium and extreme long shots, and also gets some fun out of the way that the windows of the bus frame the rear projection screens behind. And that's something to touch on: Torn Curtain has some simply awful rear projection sequences, including one particularly hideous scene when Michel and Sarah are at an outdoor café together, with all angles of the outside played by exceptionally grainy, flat projection; the angles on Newman in particular are so dreadful that one can almost tell how many feet he's sitting in front of the projection screen. And yes, bad rear projection is one of the things that we've all tacitly agreed to find charming in Hitchcock, but this is awful, the clearest single sign of what a slapdash, don't-give-a-shit production this was.

Anyway, that's two good sequences, three if we count the opening bedroom scene; there are a few others where you recall this that this is a thriller made by an expert in the form, but not nearly enough. And several of the ones that start well (like a white-knuckle "waiting for a clerk at the post office" scene) run out of steam. There are also some good, or at least energetic small roles played by actors who clearly captured more of the director's attention than the stars. The best of these are the menacing guard Gromek (Wolfgang Kieling), and the desperate Polish refugee Countess Kuchinska (Lila Kedrova), the latter providing a much-needed injection of pure stylistic anarchism at a point when the film is at its most sluggish with her expressive, broad cartoon of a desperate woman who also serves as the focal point for the only genuinely political material in this Cold War thriller, as she rambles about the difficulty of finding a Western sponsor to get the hell out of Germany. While these side characters draw maximum attention to how disconnected and episodic this is, and how insufficient the leads are, they still represent just about the only part of the film that has any real liveliness or humor.

Otherwise, there's a very dreary sense that the film is being gotten through. It's 128 minutes long, not a particularly outrageous length for the amount of incident and the genre, but it's full of droning moments that find the characters talking about the plot until they can move to the next part. The most important part of nearly every Hitchcock film is that it is fun; that it has a certain cinematic brio, at least, that feels creative for the sake of it. Throughout the '60s, his films had been getting less fun, to be sure, but they still have style and flash and a desire to entertain, and I get none of that from Torn Curtain. There's nothing more openly energetic than its flighty, trite score by John Addison (replacing Bernard Herrmann, whose longstanding relationship with Hitchcock never recovered from the slight), and he has such a generic sense of humor that he uses a couple bars of "Funeral March for a Marionette", the theme music for Alfred Hitchcock Presents on television, to leadenly point out Hitchcock's cameo and suck all the joy out of it. It has some strange angles and compositions, ones that feel like they're trying to force some kind of confrontation between the viewer and the onscreen events, though these seems less like part of a smart strategy and more like a desperate attempt by a bored director to amuse himself by being weird. It doesn't seem to have worked for him; it certainly didn't work for me. Torn Curtain is neither the worst nor the dullest Hitchcock film, but it's pretty damn hard to like, and an unpleasantly strong suggestion that the director, having made such a commanding number of masterpieces in the preceding three decades, was simply running out of things to say and ways of saying them.

It shows. This isn't the most detached that I've ever felt this director to be from his material - one doesn't get the sad aura of complete capitulation that we find from him 1939's Jamaica Inn, a joyless Charles Laughton period piece - but it's extremely clear that he didn't want to make this film, at least not the way he had to make it. There are a few good moments that would work as one of the lesser setpieces in one of his masterpieces, and a good handful of colorful side characters who sweep into the film with blast of personality, so he's not completely checked out. But given how strong the plot hook is - a plot hook that Hitchcock came up with himself, before sending it to screenwriter Brian Moore to make a script out of it - it's slightly agonising how much the plot drags, and how little is made out of the most promising angles on the story.

That story is an original spy thriller, inspired by a pair of British men who defected to the Communist East: more specifically, with the wife of one of those men, who packed up their children several weeks later and defected right after him. The question the film tackles: what must have been going through her mind while she did that? In this case, a whole lot of panicky mistrust. Professor Michael Armstrong (Newman), an American physicist, is traveling to a European conference with his fiancée and assistant (ah, the '60s!), Sarah Sherman (Andrews). He's already acting a little strange on the boat trip over, and he gets stranger still once they've arrived in Copenhagen; soon enough, she's managed to surreptitiously follow him enough that she's on a plane several rows behind him, traveling to East Berlin, very much against his wishes. Upon landing, she learns the horrible truth: he's defecting.

We then immediately switch over the Michael's perspective on events, to learn that he's doing no such thing. In fact, he's faking defection, in order to dig up some secrets that will help with his research on anti-missile technology for the U.S. government. This means he not only has to safely navigate East Germany without any formal training in espionage, he also has to deal with the destablising presence of Sarah, who has looked deep inside herself, and with great reluctance, committed herself to actually defecting, in order to stay with Michael. Eventually, all of this gets smoothed out, but it's taken enough effort, and there have been enough missteps along the way, that the reunited lovers are now obliged to engage in a delicate, complex hunt across a hostile country to escape the increasingly suspicious East German officials.

That's two different levels on which this really ought to work: the idea of mixing love with high-stakes espionage, and even implicitly finding that espionage adds a certain erotic spice to one's romantic partnership, is vintage Hitchcock stretching all the way back to The 39 Steps from 1935 (a film whose three-part structure is echoed here) and The Man Who Knew Too Much from 1934. Meanwhile, telling a story that switches character perspectives so dramatically as this one does when it hops from Sarah's shoulder to Michael's is a suitable experiment in feeding the audience information in a way that challenges and upsets our understanding of how movies work, a fine extension of similar games played in 1950's Stage Fright and 1958's Vertigo. Even so, the storytelling here is shapeless and slack. Especially in its third phase, Torn Curtain becomes nothing but a fetch quest, schlepping the characters from one location to another in scenes that hang together in the most brutally literal sense, but don't have the wonderful sense of events spilling over that marks the best of Hitch's earlier "crisscross a nation chasing clues" films, like The 39 Steps or 1959's North by Northwest. It just clicks methodically from scene to scene, and from supporting character to supporting character.

The big problem is that the film gives up on Michael and Sarah almost immediately. It seems like we're on good footing at the very start: the film's opening is very fussy and mannered in a way that feels exactly like a '30s elegant comedy, using a motif of name tags on lapels to introduce us to the shipful of traveling physicists before using it to show Michael and Sarah's clothed draped over the chair next to the bed where they're rolling around with each other. And how much of a joy it must have been to Hitchcock to get to show his very first (albeit entirely chaste) sex scene, which is perhaps why this scene feels so emotionally charged: he shows both lovers in extreme close-ups in romantic soft focus, capturing something of the playful eroticism of two people comfortable with each other's bodies. It's a great kick-off to a love story that immediately face-plants: there will never be another moment for the rest of Torn Curtain when Newman and Andrews have any particular chemistry at all. Neither actor is doing particularly good solo work, either: Newman's performance is charmless and brusque, one of the worst screen performances I've ever seen him give, while Andrews is merely bland an insubstantial.

That's basically the film, once it becomes clear how meager the leads are going to be. There are some moments that work mechanically, most famously a death scene that goes on and on for endless seconds, while the view cuts around to increasingly baroque angles on the action. It's the one moment Hitchcock owned to being happy with, his way of mocking the spy thrillers that had become a fixture of European and American cinema in the few years since James Bond made his first appearance, with their exciting lack of weight to human morality. I might add to that a bus sequence near the end makes good use of a variation between medium and extreme long shots, and also gets some fun out of the way that the windows of the bus frame the rear projection screens behind. And that's something to touch on: Torn Curtain has some simply awful rear projection sequences, including one particularly hideous scene when Michel and Sarah are at an outdoor café together, with all angles of the outside played by exceptionally grainy, flat projection; the angles on Newman in particular are so dreadful that one can almost tell how many feet he's sitting in front of the projection screen. And yes, bad rear projection is one of the things that we've all tacitly agreed to find charming in Hitchcock, but this is awful, the clearest single sign of what a slapdash, don't-give-a-shit production this was.

Anyway, that's two good sequences, three if we count the opening bedroom scene; there are a few others where you recall this that this is a thriller made by an expert in the form, but not nearly enough. And several of the ones that start well (like a white-knuckle "waiting for a clerk at the post office" scene) run out of steam. There are also some good, or at least energetic small roles played by actors who clearly captured more of the director's attention than the stars. The best of these are the menacing guard Gromek (Wolfgang Kieling), and the desperate Polish refugee Countess Kuchinska (Lila Kedrova), the latter providing a much-needed injection of pure stylistic anarchism at a point when the film is at its most sluggish with her expressive, broad cartoon of a desperate woman who also serves as the focal point for the only genuinely political material in this Cold War thriller, as she rambles about the difficulty of finding a Western sponsor to get the hell out of Germany. While these side characters draw maximum attention to how disconnected and episodic this is, and how insufficient the leads are, they still represent just about the only part of the film that has any real liveliness or humor.

Otherwise, there's a very dreary sense that the film is being gotten through. It's 128 minutes long, not a particularly outrageous length for the amount of incident and the genre, but it's full of droning moments that find the characters talking about the plot until they can move to the next part. The most important part of nearly every Hitchcock film is that it is fun; that it has a certain cinematic brio, at least, that feels creative for the sake of it. Throughout the '60s, his films had been getting less fun, to be sure, but they still have style and flash and a desire to entertain, and I get none of that from Torn Curtain. There's nothing more openly energetic than its flighty, trite score by John Addison (replacing Bernard Herrmann, whose longstanding relationship with Hitchcock never recovered from the slight), and he has such a generic sense of humor that he uses a couple bars of "Funeral March for a Marionette", the theme music for Alfred Hitchcock Presents on television, to leadenly point out Hitchcock's cameo and suck all the joy out of it. It has some strange angles and compositions, ones that feel like they're trying to force some kind of confrontation between the viewer and the onscreen events, though these seems less like part of a smart strategy and more like a desperate attempt by a bored director to amuse himself by being weird. It doesn't seem to have worked for him; it certainly didn't work for me. Torn Curtain is neither the worst nor the dullest Hitchcock film, but it's pretty damn hard to like, and an unpleasantly strong suggestion that the director, having made such a commanding number of masterpieces in the preceding three decades, was simply running out of things to say and ways of saying them.