By the sea

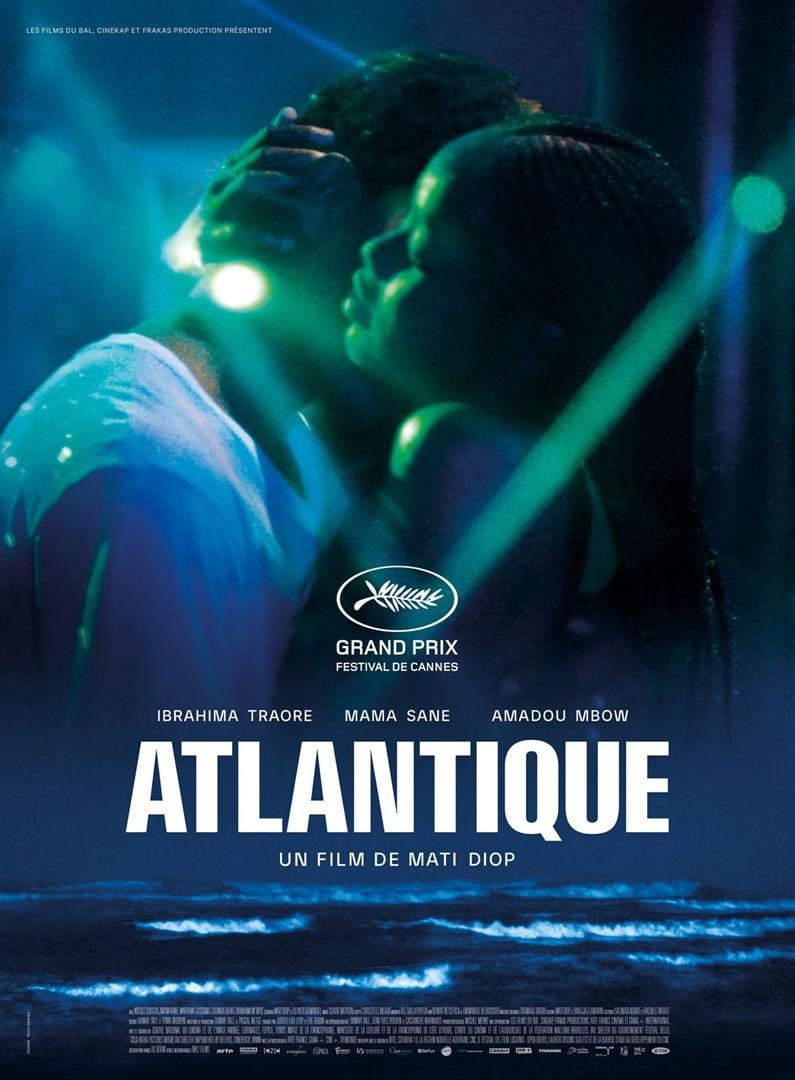

It is occasionally the case that a film has such a perfect first shot that, the moment it appears before your eyes, you already know that you're about to see a masterpiece. Atlantics has such a first shot: a sleek new skyscraper rising in the background above a street in Dakar, capitol city of Senegal. It dominates the composition, dwarfing the small dots in the mid-ground that we can just barely clearly make out as humans. Meanwhile, the colors are all skewed towards reds and oranges and faded, the focus perversely diffused, and the whole thing feels more like a painting than photography, as though someone was trying to capture their impressions of a sunset while they were falling asleep. It's a gorgeous, ominous opening image, suggesting both the hazy dreaminess of the uncanny sun, and the brutal imposition of state-of-the-art industry, stripping the life from the community into which it has erupted. These are exactly the things the film will be concerned with, so it's not just striking in its own right, but a well-chosen bit of priming for the whole movie to follow.

In fact, it has such a perfect first shot that it does even more: it told me, within seconds of meeting her, that first-time feature director Mati Diop is a miraculous talent, and if there is a shred of justice in the world, this film is going to unlock every single door she could ever want to step through. But for right now at least we have this astoundingly confident, bold, uncanny debut to to gawk at, and prod at, trying to tease out all of its depths and mysteries.

Of which there are a significant number, and some of them aren't even mysteries until the answer comes along to up-end everything we thought the movie was. God forbid I should spoil the surprise, so let me offer only a little sketch of the plot: in suburban Dakar, a state-of-the-art skyscraper is under construction, and the locals who've worked on it are in a state of crisis. It's been three months since anyone has been paid, and these are not people with three months of financial wiggle room. We could presumably zoom in on any one of these workers, but the one Diop and co-writer Olivier Demangel have selected is Souleiman (Ibrahima Traoré), and that's mostly so we can meet his lover, Ada (Mame Bineta Sane), who is unhappily engaged to a much wealthier man, Omar (Babacar Sylla). And the reason we need to meet up with Ada as soon as possible is that, despite the momentum of the earliest scenes, Souleiman won't end up being around long enough to serve as our protagonist: he and all of the other men leave go to sea one night to look elsewhere for their fortune, and are never seen again.

That's the first swerve of a great many in a film that takes great pleasure in making sure that we never get in front of it. What begins as a fairly standard realist study of life in poverty-stricken West Africa (inasmuch as films on that subject are "standard", you know what I mean) ends as a magical realist love story, after having flirted with being psychologically impressionistic slow cinema, a police procedural, and horror. What's impressive isn't that Atlantics makes all of these changes, but that it never struggles to do so: from beginning to end, the film glides through its 106 minutes with perfect focus, missing a step only briefly in its incorporation of Detective Issa (Amadou Mbow), who feels like an intrusion from a different story. And even this ends up being justified by the film, which pulls Issa and his subplot into the main emotional throughline of the movie so surprisingly and persuasively that it almost feels like it was intentional that it felt like a foreign element at first.

The anchor for all of this ends up being Ada herself, both as a character in a drama, and an emotional perspective. Atlantics is an extraordinarily impressionistic movie, and we might as well suppose that it's Ada's impressions we're receiving. Or maybe they're the impressions of Dakar itself. The film's title points towards that city's unique status as the westernmost point on mainland Africa, residing on the tip of a peninsula jutting out into the Atlantic Ocean, a scrap of land clinging to the continent as the sea bashes it from three sides. Atlantics gets a great deal of mileage from the city's location: in particular, it uses the cyclical sound of ocean waves as the bedrock for its soundtrack, an omnipresent rushing back and forth that quickly moves from straightforward realistically-motivated place-setting to an unbearable, maddening reminder of the wretched, isolating water surrounding and threatening the city.

This emphasis on natural rhythms creates a mood that matched wonderfully in the fuzzy images and uncanny color of Claire Mathon's cinematography (Mathon had probably the best 2019 of any individual human involved in filmmaking: she shot this and Portrait of a Lady on Fire, quite possibly the two best-looking films of the year). And both are perfectly set off by Fatima Al Qadri's electronic score, slightly tensed-up even as it has the gauzy droning quality of a dozing afternoon. All told, it is a blatantly poetic film, finding an outlet for Ada's tight-lidded despair in the very texture of the air and the way that the notorious skyscraper always seems to loom no matter what angle of the city we're seeing. Sane's performance through all of this is impossibly good: the abstract needs of the film insist on her remaining taciturn and aloof, at times more an object onto which the film and the viewer can project our sense of what emotions develop out of the film, than a fleshed-out human figure. And at other times, she feels things so hard that it's almost impossible to withstand it. And this is all accomplished without Sane herself visibly shifting her performance: it's a tightly-wound performance that occasionally melts into bursts of expression, always worked so neatly into the story and captured so perfectly in the slightly remote frame that it invariably feels natural.

Diop's remarkably bravery and sensitivity in presenting all of this isn't totally sui generis. She had two excellent influences: as actor, she appeared in Claire Denis's wonderful 35 Shots of Rum, from 2008; and she is the niece of Djibril Diop Mambéty, whose 1973 Touki Bouki is one of the best films of the 1970s. There's a bit of both of those filmmakers in Atlantics: the collision of politically-tinged realism with a dreamy subjectivity that feels otherworldly without always doing anything explicitly unreal. But it would be grossly reductive to declare that she's just borrowing from those masters. Atlantics is very much its own thing, a complex and surprising and quietly challenging art film of the very best sort, something that feels a little bit like many other films, but exactly like none of them. It presents us with a brand new way to think about the world, human relationships, and the suffering of the Senegalese lower classes entirely through its application of style and story structure, and I can't think of a more sure-footed debut film from the whole of the decade now ending.

In fact, it has such a perfect first shot that it does even more: it told me, within seconds of meeting her, that first-time feature director Mati Diop is a miraculous talent, and if there is a shred of justice in the world, this film is going to unlock every single door she could ever want to step through. But for right now at least we have this astoundingly confident, bold, uncanny debut to to gawk at, and prod at, trying to tease out all of its depths and mysteries.

Of which there are a significant number, and some of them aren't even mysteries until the answer comes along to up-end everything we thought the movie was. God forbid I should spoil the surprise, so let me offer only a little sketch of the plot: in suburban Dakar, a state-of-the-art skyscraper is under construction, and the locals who've worked on it are in a state of crisis. It's been three months since anyone has been paid, and these are not people with three months of financial wiggle room. We could presumably zoom in on any one of these workers, but the one Diop and co-writer Olivier Demangel have selected is Souleiman (Ibrahima Traoré), and that's mostly so we can meet his lover, Ada (Mame Bineta Sane), who is unhappily engaged to a much wealthier man, Omar (Babacar Sylla). And the reason we need to meet up with Ada as soon as possible is that, despite the momentum of the earliest scenes, Souleiman won't end up being around long enough to serve as our protagonist: he and all of the other men leave go to sea one night to look elsewhere for their fortune, and are never seen again.

That's the first swerve of a great many in a film that takes great pleasure in making sure that we never get in front of it. What begins as a fairly standard realist study of life in poverty-stricken West Africa (inasmuch as films on that subject are "standard", you know what I mean) ends as a magical realist love story, after having flirted with being psychologically impressionistic slow cinema, a police procedural, and horror. What's impressive isn't that Atlantics makes all of these changes, but that it never struggles to do so: from beginning to end, the film glides through its 106 minutes with perfect focus, missing a step only briefly in its incorporation of Detective Issa (Amadou Mbow), who feels like an intrusion from a different story. And even this ends up being justified by the film, which pulls Issa and his subplot into the main emotional throughline of the movie so surprisingly and persuasively that it almost feels like it was intentional that it felt like a foreign element at first.

The anchor for all of this ends up being Ada herself, both as a character in a drama, and an emotional perspective. Atlantics is an extraordinarily impressionistic movie, and we might as well suppose that it's Ada's impressions we're receiving. Or maybe they're the impressions of Dakar itself. The film's title points towards that city's unique status as the westernmost point on mainland Africa, residing on the tip of a peninsula jutting out into the Atlantic Ocean, a scrap of land clinging to the continent as the sea bashes it from three sides. Atlantics gets a great deal of mileage from the city's location: in particular, it uses the cyclical sound of ocean waves as the bedrock for its soundtrack, an omnipresent rushing back and forth that quickly moves from straightforward realistically-motivated place-setting to an unbearable, maddening reminder of the wretched, isolating water surrounding and threatening the city.

This emphasis on natural rhythms creates a mood that matched wonderfully in the fuzzy images and uncanny color of Claire Mathon's cinematography (Mathon had probably the best 2019 of any individual human involved in filmmaking: she shot this and Portrait of a Lady on Fire, quite possibly the two best-looking films of the year). And both are perfectly set off by Fatima Al Qadri's electronic score, slightly tensed-up even as it has the gauzy droning quality of a dozing afternoon. All told, it is a blatantly poetic film, finding an outlet for Ada's tight-lidded despair in the very texture of the air and the way that the notorious skyscraper always seems to loom no matter what angle of the city we're seeing. Sane's performance through all of this is impossibly good: the abstract needs of the film insist on her remaining taciturn and aloof, at times more an object onto which the film and the viewer can project our sense of what emotions develop out of the film, than a fleshed-out human figure. And at other times, she feels things so hard that it's almost impossible to withstand it. And this is all accomplished without Sane herself visibly shifting her performance: it's a tightly-wound performance that occasionally melts into bursts of expression, always worked so neatly into the story and captured so perfectly in the slightly remote frame that it invariably feels natural.

Diop's remarkably bravery and sensitivity in presenting all of this isn't totally sui generis. She had two excellent influences: as actor, she appeared in Claire Denis's wonderful 35 Shots of Rum, from 2008; and she is the niece of Djibril Diop Mambéty, whose 1973 Touki Bouki is one of the best films of the 1970s. There's a bit of both of those filmmakers in Atlantics: the collision of politically-tinged realism with a dreamy subjectivity that feels otherworldly without always doing anything explicitly unreal. But it would be grossly reductive to declare that she's just borrowing from those masters. Atlantics is very much its own thing, a complex and surprising and quietly challenging art film of the very best sort, something that feels a little bit like many other films, but exactly like none of them. It presents us with a brand new way to think about the world, human relationships, and the suffering of the Senegalese lower classes entirely through its application of style and story structure, and I can't think of a more sure-footed debut film from the whole of the decade now ending.