Paint and glory

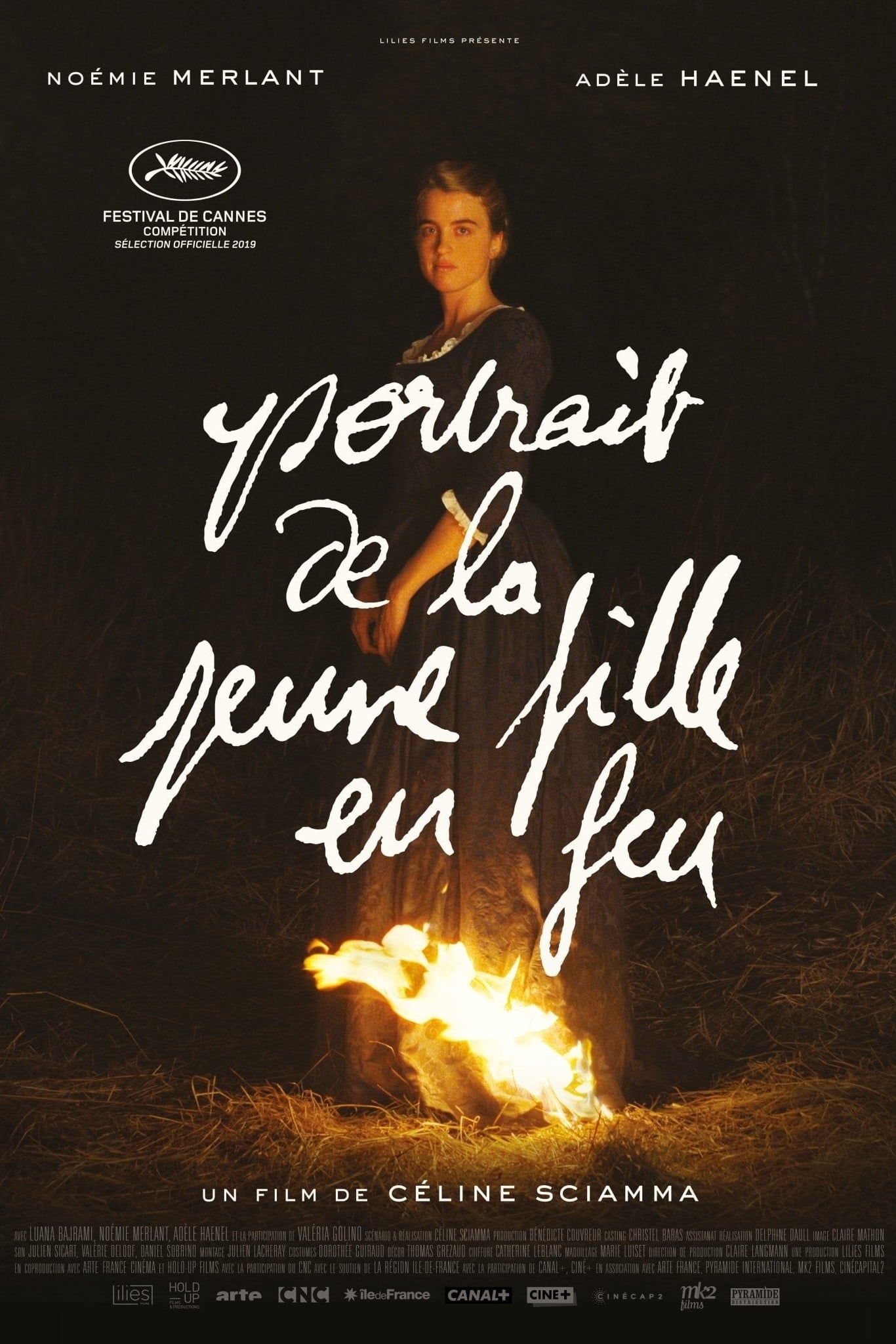

Before I saw Portrait of a Lady on Fire, I was thinking I'd maybe start this review by point out how the 2010s weirdly became the decade of the lesbian romantic drama, and how the three best love stories of the decade to this point, 2014's The Duke of Burgundy, 2015's Carol, and 2016's The Handmaiden, were all about relationships between women but directed by men, and isn't that an odd something that we could probably make something out of. Now that I've seen the film, I am absolutely no longer interested in doing that. Talking about Portrait of a Lady on Fire in that way might give somebody the idea that the film can be neatly put in a little box and kept contained and thought about like it's just another movie. And that is wrong. This is an unabashed masterpiece, something that feels like it's already survived decades of adoration to be heralded as one of the great art films that everybody stands so far back in awe of that we lose sight of how rich and approachable and human it is. Playing historian in advance is a fool's errand, but I'll say with the brash confidence of pure love: if there's one single film from 2019 that's still being talked about and loved by cinephiles 25 years from now, it's going to be this one.

It's a simple, clean scenario, just like all the best love stories have: in the latter half of the 18th Century Marianne (Noémie Merlant) has been hired by a countess (Valeria Golina) to come to an isolated island in Brittany, to paint a portrait of her daughter Héloïse (Adèle Haenel); this portrait is being sent to the man whom the countess has selected as Héloïse's fiancé, and whom the young woman has never met. Marianne will not be the first artist to take on this job; Héloïse, it turns out, has defeated other painters with her refusal to pose. So Marianne is officially coming to be her walking companion, meant to use that time to carefully study the young woman's facial features and body so that she can later paint from memory. And oh, how Marianne does end up carefully studying her facial features and body.

Portrait of a Lady on Fire is a great film about falling and being in love, but it is also, and maybe even more crucially, a great film about painting. These facts are tightly related. The film trains its viewer's eye: in voiceover, Marianne talks about how a painter looks at an ear, as a series of lines, shadows, curves, all centered around a strong dark dot. And this is really the only cue the movie needs to offer for us to see what writer-director Céline Sciamma and cinematographer Claire Mathon are up to with their extraordinary images. The film breaks into two halves (the second is slightly longer), and the first half is simply about looking: about closely observing lines and color, light and shadow, the inner glow of skin. It is an unbelievable sensual movie. Colors seem to radiate right off the screen, both of the natural world and in the boldly primary-color costumes designed by Dorothée Guiraud; the early scenes of Marianne riding on a boat towards the island are themselves a quick little lesson in watching, as the film makes sure that we can handle the overwhelming azure of the sea and the rich dark wine colors of Marianne's outfit contrast with each other, without our eyes melting away into a puddle of blissful overstimulation. I am not joking by very much. It is a film that demands we look at it for fine details, the way a strand of hair blows in the wind, the way a nose connects to a face, how hands pick up the reflected hue of silky clothing. It doesn't look like a painting: it overwhelming and vivid and far too rich and pungent to resemble the art of the 18th Century in any way. But it looks like the way a highly attuned artist might see the world, absorbing all the too-muchness and finding a way to tame it and translate it, and as we watch Marianne paint, we see that process happen in real time. It is almost indescribably rewarding.

Other than painters, of course, there's another kind of person who thinks constantly about things like the fold of ears and the shape of somebody's nose, and that's a lover. And this is the other half of Portrait of a Lady on Fire: it is a depiction of exquisite, overpowering ardor, created by and manifested in the act of looking intently, devouring and caressing one's love object with one's eyes, trying to see every molecule of what makes them a whole. It's definitely no accident that Sciamma and Haenel are themselves former lovers, or that the film was built in part for Haenel to take this role: it is a movie that comes from a place of extreme intimacy with her face, knowing every crease by her eyes and the way her mouth can move, and using that face (or its painted replica) as the centerpiece of the most emotionally heady images I've seen all year. The very story of the film is basically just about whether Marianne will be able to paint that face in its details, not as it is but as she, the person in love with that face, experiences it, and it's a boon to the film that, in the form of painter Hélène Delmaire, it found someone who could craft those crucial props to make it so clear how Marianne feels about her subject, even when it's nothing more than a series of lines sketching out Héloïse's eyes.

It's an exhausting film, and it gets more exhausting still as it barrels towards the ending (the last ten minutes, and the last shot in particular, basically dare you not to breathe or blink), but this is what makes it a great love story. It's not meant to be mild and pleasant; it's meant to feel like flying and drowning simultaneously. It's profoundly erotic without being in the least bit prurient, hyper-aware of the pleasures of the body as an object (the first spoken words the film are Marianne telling a group of art students, years after the events of the rest of the plot, "D'acord, mes contours", or "First, my contours", and I cannot think of a more sensuous opening line), but never dirty or leering about it, and this despite having full-frontal nudity. So erotic, but not lustful, if that follows. After so many years of austere French art films about fucking, this is a lavish, poetic French art film about making love, and incredibly satisfying as a result. For it has reminded me of the important fact that French art film, when everything is going right, is just about as overwhelmingly, intoxicatingly gripping as cinema gets. And it's not enough to say that everything is going right in Portrait of a Lady on Fire; everything is going perfectly.

It's a simple, clean scenario, just like all the best love stories have: in the latter half of the 18th Century Marianne (Noémie Merlant) has been hired by a countess (Valeria Golina) to come to an isolated island in Brittany, to paint a portrait of her daughter Héloïse (Adèle Haenel); this portrait is being sent to the man whom the countess has selected as Héloïse's fiancé, and whom the young woman has never met. Marianne will not be the first artist to take on this job; Héloïse, it turns out, has defeated other painters with her refusal to pose. So Marianne is officially coming to be her walking companion, meant to use that time to carefully study the young woman's facial features and body so that she can later paint from memory. And oh, how Marianne does end up carefully studying her facial features and body.

Portrait of a Lady on Fire is a great film about falling and being in love, but it is also, and maybe even more crucially, a great film about painting. These facts are tightly related. The film trains its viewer's eye: in voiceover, Marianne talks about how a painter looks at an ear, as a series of lines, shadows, curves, all centered around a strong dark dot. And this is really the only cue the movie needs to offer for us to see what writer-director Céline Sciamma and cinematographer Claire Mathon are up to with their extraordinary images. The film breaks into two halves (the second is slightly longer), and the first half is simply about looking: about closely observing lines and color, light and shadow, the inner glow of skin. It is an unbelievable sensual movie. Colors seem to radiate right off the screen, both of the natural world and in the boldly primary-color costumes designed by Dorothée Guiraud; the early scenes of Marianne riding on a boat towards the island are themselves a quick little lesson in watching, as the film makes sure that we can handle the overwhelming azure of the sea and the rich dark wine colors of Marianne's outfit contrast with each other, without our eyes melting away into a puddle of blissful overstimulation. I am not joking by very much. It is a film that demands we look at it for fine details, the way a strand of hair blows in the wind, the way a nose connects to a face, how hands pick up the reflected hue of silky clothing. It doesn't look like a painting: it overwhelming and vivid and far too rich and pungent to resemble the art of the 18th Century in any way. But it looks like the way a highly attuned artist might see the world, absorbing all the too-muchness and finding a way to tame it and translate it, and as we watch Marianne paint, we see that process happen in real time. It is almost indescribably rewarding.

Other than painters, of course, there's another kind of person who thinks constantly about things like the fold of ears and the shape of somebody's nose, and that's a lover. And this is the other half of Portrait of a Lady on Fire: it is a depiction of exquisite, overpowering ardor, created by and manifested in the act of looking intently, devouring and caressing one's love object with one's eyes, trying to see every molecule of what makes them a whole. It's definitely no accident that Sciamma and Haenel are themselves former lovers, or that the film was built in part for Haenel to take this role: it is a movie that comes from a place of extreme intimacy with her face, knowing every crease by her eyes and the way her mouth can move, and using that face (or its painted replica) as the centerpiece of the most emotionally heady images I've seen all year. The very story of the film is basically just about whether Marianne will be able to paint that face in its details, not as it is but as she, the person in love with that face, experiences it, and it's a boon to the film that, in the form of painter Hélène Delmaire, it found someone who could craft those crucial props to make it so clear how Marianne feels about her subject, even when it's nothing more than a series of lines sketching out Héloïse's eyes.

It's an exhausting film, and it gets more exhausting still as it barrels towards the ending (the last ten minutes, and the last shot in particular, basically dare you not to breathe or blink), but this is what makes it a great love story. It's not meant to be mild and pleasant; it's meant to feel like flying and drowning simultaneously. It's profoundly erotic without being in the least bit prurient, hyper-aware of the pleasures of the body as an object (the first spoken words the film are Marianne telling a group of art students, years after the events of the rest of the plot, "D'acord, mes contours", or "First, my contours", and I cannot think of a more sensuous opening line), but never dirty or leering about it, and this despite having full-frontal nudity. So erotic, but not lustful, if that follows. After so many years of austere French art films about fucking, this is a lavish, poetic French art film about making love, and incredibly satisfying as a result. For it has reminded me of the important fact that French art film, when everything is going right, is just about as overwhelmingly, intoxicatingly gripping as cinema gets. And it's not enough to say that everything is going right in Portrait of a Lady on Fire; everything is going perfectly.