Wherein we'll catch the conscience of the king

A review requested by Nathan Morrow, with thanks to supporting Alternate Ending as a donor through Patreon.

Do you have a movie you'd like to see reviewed? This and other perks can be found on our Patreon page!

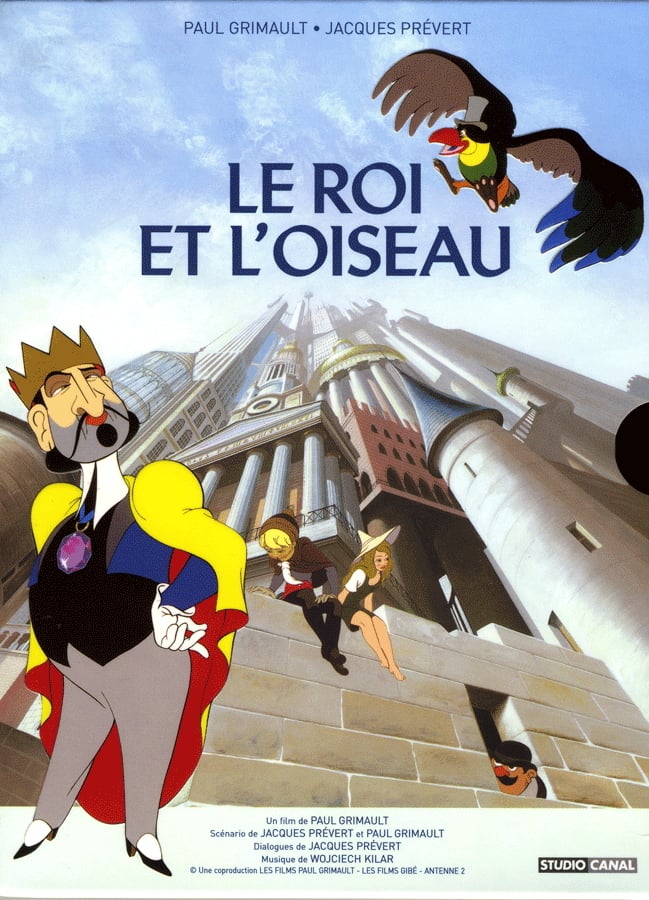

It's impossible to talk about The King and the Mockingbird without talking about its torturous path into the world: it was in production for 32 years, the longest period in production for any completed animated feature (longer than the 29 years that Richard Williams's legendary The Thief and the Cobbler was in production, and that was never even completed). It started life in 1948, when animator Paul Grimault and poet Jacques Prévert decided to join forces to make an adaptation of Hans Christian Andersen's "The Shepherdess and the Chimney Sweep", the story of two china dolls who come to life and fall in love, but are menaced by a wooden figurine. Their take was much different than Andersen's, taking an avowedly satirical approach towards authoritarian tyrants, making fairly particular jabs at the recently-deceased Adolf Hitler. It was a tremendously ambitious project for post-war France: it would have been the second 2-D animated feature in the country's history, and the first with even a scintilla of artistic aspiration. And in 1950, it was snatched away from Grimault and Prévert by producer André Serrut, who released it in 1952 in a hastily-completed version that both of the original creators disowned. Grimault was able to re-acquire the rights to the project in 1967, and was able to arrange financing by 1977, right around the time that Prévert died. The film was released under its new title in 1980, as a hybrid of 42 minutes of footage completed in the original production and 45 minutes of new animation, as well as a brand-new soundtrack.

The resultant film is a thoroughly baffling beast - though to be fair, it likely would have been no matter what, given the film's slippery dive into a delirium of a kind that nobody was really doing much of in the early '50s, definitely not in animation. The plot includes most of Andersen's story, with some major changes, but goes very far beyond it. To begin with, we have the bird, voiced by Jean Martin, giving us a lustful introduction to the story that will follow that's less "once upon a time", more like the ebullient showmanship of a boulevard raconteur from fin de siècle Paris. Thus he introduces us to the much hated tyrant King Charles V + III = VIII + VIII = XV of Takicardia (Pascal Mazzotti), a vain fop whose love of hunting left the bird a widower father of four chicks. For this reason, the bird has made it his life's work to make the king as miserable as possible, as often as possible.

The king, for his part, is a mean little monster, eager to surround himself with artwork that makes him look as good as possible - a neat trick, given his clammy white skin, his cross eyes, his lack of a chin, and his body shaped like a slumped pudding. On the particular day we meet him, the king is sitting for an unfortunately honest portrait, and after having the painter executed, he himself makes the corrections to the eyes in his portrait. Putting it up for the night he retires, and then we find that all of the artworks in the king's crowded gallery come to life. The only ones we particularly need to worry about are the paintings of a shepherdess (Agnes Viala) and a chimney sweep (Renaud Marx), hung near enough to each other that they have fallen very much in love. Unfortunately, the new portrait of the king also comes to life, and decides that he deserves to have the shepherdess for himself. While the painted lovers sit on the roof of the palace, enjoying the night sky, the painted king manages to depose the real king, and arrange a particularly nasty fate for both the bird and the chimney sweep. And this is only about a third of the way through the film, and the point at which the fun really starts.

Up to this point, as well, I'll admit that I wasn't quite feeling it. The King and the Mockingbird enjoys an enormous amount of acclaim for such a relatively obscure feature, and the opening act doesn't really do much to justify that cult. It's visually striking, no question. Besides the matter of a generation-long production period, the film shares with The Thief and the Cobbler an all-consuming fascination with hand drawn animation as a medium that is both entirely unreal, but capable of evoking a kind of hyper-realness. This is, for the most part, pure Looney Tunes cartoon logic: physics don't apply, even down to the level of the bodily integrity of the characters, who move with an extreme version of squash-and-stretch animation that makes them - the king, mostly - look like bags of fluid rolling into new poses. It's eerily smooth, with a gracefulness that contrasts wildly with the self-consciously ugly design of most of the humans (the shepherdess and chimney sweep are ugly, but not self-consciously). The tangible presence of these strange, distorted figures is damn disorienting, even when the plot is at its most sedate.

And all I've said thus far is the plot at its most sedate. I frankly don't know if one could communicate, even with a minutely-detailed summary, how it feels to watch the last hour of The King and the Mockingbird. It's pure associative dream logic, creating a world in which the only steady constant is that the king's whims are law, and everybody suffers from those whims. As you're watching it, the movement from living paintings to a dismal under-city where nobody has ever seen daylight, to a pit of dancing tigers and lions doesn't just make sense; it feels downright inevitable. It's here where the raves about The King and the Mockingbird finally start to make sense: it is one of the most surreal animated films that nevertheless completely obeys the rules of cartoon realism I can imagine. Not that I could imagine this. It is, at any rate, a nightmare of life under a petty, vain tyrant that uses the instability of the world and the fluidity of the images as themselves the vehicle for that nightmare, in so many big and little ways that I wouldn't know where to start talking about them. So I'll just go with one: at one point, the shepherdess and the chimney sweep are running from a spotlight, which illuminates their silhouettes as ragged, almost worm-like assemblages of flailing limbs. These are our heroes, mind you: transformed into Expressionist monstrosities simply by the process of living and acting in this society.

It's an exhausting, exciting use of animation's unique power of moving caricature, and despite how frankly pokey I found the first third of the plot, I'd be ready to declare it a masterpiece right here and right now, except for one major problem: it's not consistent. The two phases of the film don't match up: I have no idea what talent pool Grimault was drawing from either in the 1940s or the 1970s, but if I had to guess, I'd say that the latter phase was mostly stocked with TV-trained animators. There's a crispness to a lot of the animation that resembles the graphic, line-drawing style of 1970s TV animation visible throughout, most damagingly in the lion pit sequence, where the muscular, snarling beasts of the 1940s material are occasionally replaced by squared-off kiddie-friendly cartoons. It's not generally that obvious when the shift happens - in particular, the 1970s animators do extremely right by the king, and mostly okay by the bird - but there's always a noticeable uptick in the saturation and solidity of the colors that doesn't quite fit right with the more muted, mottled look of the original footage. It could easily be this is purely down to the age of the materials, but that doesn't make it less visible, nor does it change the fact that all of the most enjoyable amorphous, dreamy footage has to keep making room with far simpler drawings that don't move so nervously as the seemingly constant twitching of even background characters in the original footage.

Still, even with the unavoidable limitations imposed by its asinine production woes, that sense of radical madness is never more than a beat away. This is an aggressive animated film, a more overtly political and philosophical match for the aesthetic anarchism that Warner Bros. and UPA were just starting to play with in the United States, using the stuff of fairy tales and funny talking animals to get at something much more complicated than any American studio would even think about at that point. Or any other point. It's a stunning mixture of goofy comedy (that I honestly didn't find particularly funny at any point, but that's almost totally irrelevant), raging satiric humanism, and some of the most unhinged style you'll find in any animated feature to that point - by the mid-'60s, this kind of thing would be relatively commonplace in the adults-oriented animation industries of the world, but I find myself wondering if any of them would exist in their current form without even the compromised 1952 version of this footage blazing a trail.

Do you have a movie you'd like to see reviewed? This and other perks can be found on our Patreon page!

It's impossible to talk about The King and the Mockingbird without talking about its torturous path into the world: it was in production for 32 years, the longest period in production for any completed animated feature (longer than the 29 years that Richard Williams's legendary The Thief and the Cobbler was in production, and that was never even completed). It started life in 1948, when animator Paul Grimault and poet Jacques Prévert decided to join forces to make an adaptation of Hans Christian Andersen's "The Shepherdess and the Chimney Sweep", the story of two china dolls who come to life and fall in love, but are menaced by a wooden figurine. Their take was much different than Andersen's, taking an avowedly satirical approach towards authoritarian tyrants, making fairly particular jabs at the recently-deceased Adolf Hitler. It was a tremendously ambitious project for post-war France: it would have been the second 2-D animated feature in the country's history, and the first with even a scintilla of artistic aspiration. And in 1950, it was snatched away from Grimault and Prévert by producer André Serrut, who released it in 1952 in a hastily-completed version that both of the original creators disowned. Grimault was able to re-acquire the rights to the project in 1967, and was able to arrange financing by 1977, right around the time that Prévert died. The film was released under its new title in 1980, as a hybrid of 42 minutes of footage completed in the original production and 45 minutes of new animation, as well as a brand-new soundtrack.

The resultant film is a thoroughly baffling beast - though to be fair, it likely would have been no matter what, given the film's slippery dive into a delirium of a kind that nobody was really doing much of in the early '50s, definitely not in animation. The plot includes most of Andersen's story, with some major changes, but goes very far beyond it. To begin with, we have the bird, voiced by Jean Martin, giving us a lustful introduction to the story that will follow that's less "once upon a time", more like the ebullient showmanship of a boulevard raconteur from fin de siècle Paris. Thus he introduces us to the much hated tyrant King Charles V + III = VIII + VIII = XV of Takicardia (Pascal Mazzotti), a vain fop whose love of hunting left the bird a widower father of four chicks. For this reason, the bird has made it his life's work to make the king as miserable as possible, as often as possible.

The king, for his part, is a mean little monster, eager to surround himself with artwork that makes him look as good as possible - a neat trick, given his clammy white skin, his cross eyes, his lack of a chin, and his body shaped like a slumped pudding. On the particular day we meet him, the king is sitting for an unfortunately honest portrait, and after having the painter executed, he himself makes the corrections to the eyes in his portrait. Putting it up for the night he retires, and then we find that all of the artworks in the king's crowded gallery come to life. The only ones we particularly need to worry about are the paintings of a shepherdess (Agnes Viala) and a chimney sweep (Renaud Marx), hung near enough to each other that they have fallen very much in love. Unfortunately, the new portrait of the king also comes to life, and decides that he deserves to have the shepherdess for himself. While the painted lovers sit on the roof of the palace, enjoying the night sky, the painted king manages to depose the real king, and arrange a particularly nasty fate for both the bird and the chimney sweep. And this is only about a third of the way through the film, and the point at which the fun really starts.

Up to this point, as well, I'll admit that I wasn't quite feeling it. The King and the Mockingbird enjoys an enormous amount of acclaim for such a relatively obscure feature, and the opening act doesn't really do much to justify that cult. It's visually striking, no question. Besides the matter of a generation-long production period, the film shares with The Thief and the Cobbler an all-consuming fascination with hand drawn animation as a medium that is both entirely unreal, but capable of evoking a kind of hyper-realness. This is, for the most part, pure Looney Tunes cartoon logic: physics don't apply, even down to the level of the bodily integrity of the characters, who move with an extreme version of squash-and-stretch animation that makes them - the king, mostly - look like bags of fluid rolling into new poses. It's eerily smooth, with a gracefulness that contrasts wildly with the self-consciously ugly design of most of the humans (the shepherdess and chimney sweep are ugly, but not self-consciously). The tangible presence of these strange, distorted figures is damn disorienting, even when the plot is at its most sedate.

And all I've said thus far is the plot at its most sedate. I frankly don't know if one could communicate, even with a minutely-detailed summary, how it feels to watch the last hour of The King and the Mockingbird. It's pure associative dream logic, creating a world in which the only steady constant is that the king's whims are law, and everybody suffers from those whims. As you're watching it, the movement from living paintings to a dismal under-city where nobody has ever seen daylight, to a pit of dancing tigers and lions doesn't just make sense; it feels downright inevitable. It's here where the raves about The King and the Mockingbird finally start to make sense: it is one of the most surreal animated films that nevertheless completely obeys the rules of cartoon realism I can imagine. Not that I could imagine this. It is, at any rate, a nightmare of life under a petty, vain tyrant that uses the instability of the world and the fluidity of the images as themselves the vehicle for that nightmare, in so many big and little ways that I wouldn't know where to start talking about them. So I'll just go with one: at one point, the shepherdess and the chimney sweep are running from a spotlight, which illuminates their silhouettes as ragged, almost worm-like assemblages of flailing limbs. These are our heroes, mind you: transformed into Expressionist monstrosities simply by the process of living and acting in this society.

It's an exhausting, exciting use of animation's unique power of moving caricature, and despite how frankly pokey I found the first third of the plot, I'd be ready to declare it a masterpiece right here and right now, except for one major problem: it's not consistent. The two phases of the film don't match up: I have no idea what talent pool Grimault was drawing from either in the 1940s or the 1970s, but if I had to guess, I'd say that the latter phase was mostly stocked with TV-trained animators. There's a crispness to a lot of the animation that resembles the graphic, line-drawing style of 1970s TV animation visible throughout, most damagingly in the lion pit sequence, where the muscular, snarling beasts of the 1940s material are occasionally replaced by squared-off kiddie-friendly cartoons. It's not generally that obvious when the shift happens - in particular, the 1970s animators do extremely right by the king, and mostly okay by the bird - but there's always a noticeable uptick in the saturation and solidity of the colors that doesn't quite fit right with the more muted, mottled look of the original footage. It could easily be this is purely down to the age of the materials, but that doesn't make it less visible, nor does it change the fact that all of the most enjoyable amorphous, dreamy footage has to keep making room with far simpler drawings that don't move so nervously as the seemingly constant twitching of even background characters in the original footage.

Still, even with the unavoidable limitations imposed by its asinine production woes, that sense of radical madness is never more than a beat away. This is an aggressive animated film, a more overtly political and philosophical match for the aesthetic anarchism that Warner Bros. and UPA were just starting to play with in the United States, using the stuff of fairy tales and funny talking animals to get at something much more complicated than any American studio would even think about at that point. Or any other point. It's a stunning mixture of goofy comedy (that I honestly didn't find particularly funny at any point, but that's almost totally irrelevant), raging satiric humanism, and some of the most unhinged style you'll find in any animated feature to that point - by the mid-'60s, this kind of thing would be relatively commonplace in the adults-oriented animation industries of the world, but I find myself wondering if any of them would exist in their current form without even the compromised 1952 version of this footage blazing a trail.