Blockbuster History: Arabian Nights

Every week this summer, we'll be taking an historical tour of the Hollywood blockbuster by examining an older film that is in some way a spiritual precursor to one of the weekend's wide releases. This week: Disney revives the evergreen "Arabian Nights adventure" genre with their new remake of Aladdin. The studio's original 1992 version of that film was itself significantly influenced by a much older classic that was ALSO a remake, and the green grass grew all around.

The 1924 fantasy epic The Thief of Bagdad was legendary almost from the moment it was created. By most accounts it was the most expensive film ever made up to that point, and it represented a basically unprecedented achievement in special effects technology. There are individual beats in various Italian and German silent epics that can compete with its best moments, and Hollywood's own Intolerance was still probably grander, but what The Thief of Bagdad can boast that they can't is that it is unrelentingly big. For around 140 minutes, the movie never lets up, never relaxes: it shovels pure, unmitigated SPECTACLE at our eyes, and if we agree that the main draw of Hollywood filmmaking is that it is better than any other at creating spectacular fantasies (especially in the 1920s, when World War I had financially devastated every other internationally significant film industry), then it's fair to say that The Thief of Bagdad is one of the highest achievements, maybe even the highest achievement of silent Hollywood filmmaking.

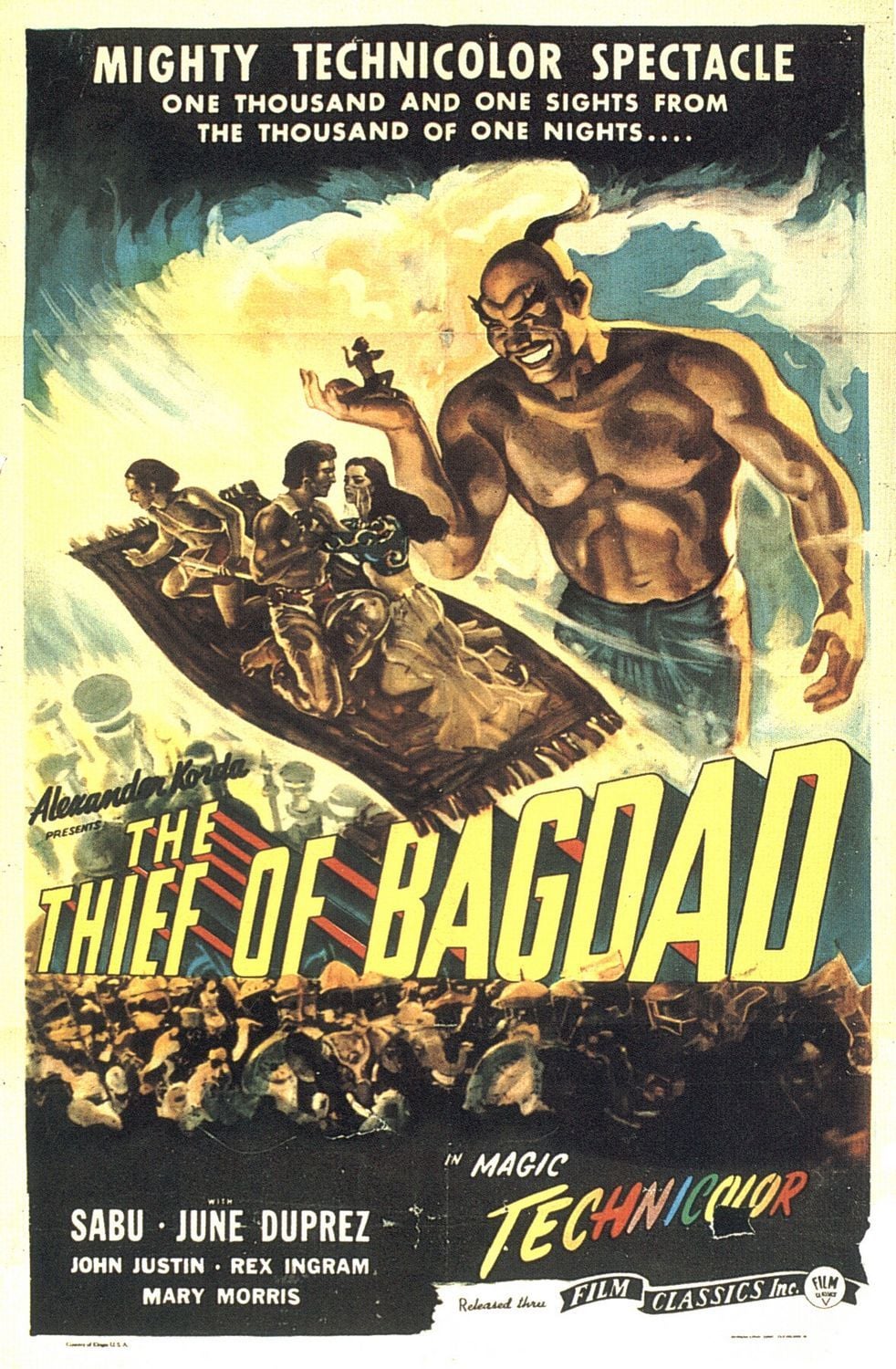

Remaking it was therefore a somewhat idiotic task, since the point of the movie wasn't "the movie" - it was the gargantuan scope and production value of the thing. So kudos to Hungarian-born British super-producer Alexander Korda: when he decided to produce his own version of The Thief of Bagdad, right on the doorstep of the Second World War, it wasn't "the movie" he was interested in, but the same promise of unprecedented spectacle. Upon its release in 1940, it's fair to say that the world had never, ever seen a special effects extravaganza on the level of the second Thief of Bagdad - 1933's King Kong is a good precedent, but it's the only one I can think of - and with the war about to knock all of human civilisation for a loop, it would be a good long time before that level would be reached. Most notably, it was the first major use of chroma key effects (better known as blue screen or green screen), and while any modern viewer is going to spot the seams without even trying, it's worth reflecting upon how long this stood as the exemplar of cinematic VFX. Looking ahead to the movies that would even attempt to do what The Thief of Bagdad did, let alone improve upon it, it's not until 1953's The War of the Worlds that I even feel compelled to slow down, and I really do think we have to get to the 1960s to find even the best-funded Hollywood productions routinely matching what this movie was up to.

It's not just the groundbreaking effects work, either. Korda, the most profligate producer in the UK at that time, wasn't looking to spare any expenses with the film's overall appearance, and the results is one of the most lavish productions in a generation (so lavish that he needed to finish making it in Hollywood after the coming war made it untenable to keep working at such a vast scale in the UK). The production design, by Korda's brother Vincent, and the Technicolor cinematography, by Georges Périnal, both won Oscars, and it's a dead certainty that if the Academy was giving out awards for costuming at this point, The Thief of Bagdad would have taken that statue too. The film is utterly sumptuous, not in any way attempting to create the illusion of a real place - the sets look like sets, the props look like props - but instead looking to supply an unending litany of lavish delights to glide your eye over, colors to suck in like a thirsty man plunging his head into a desert oasis. And sonically, the film matches its visual marvels with a robust, roiling score by Miklós Rózsa (getting the first of his 17 Oscar nominations for his work; he lost out to Leigh Harline, Paul J. Smith, and Ned Washington, for Pinocchio) that heaves with brassy, exotic instrumentation. I'm not much of a fan of Rózsa's costume drama scores, in honesty; they all sound like the same to me, all big affect with no texture. But The Thief of Bagdad was the one that sounded that way first, and so deserves all the credit for the bigness.

Within this overwhelming aesthetic, the film finds time for several elaborate action-adventure set-pieces, the most impressive of which involves a giant statue over which Korda's favorite child star, Sabu, scurries like a tiny ant while a huge spider puppet (the film's least-impressive effect, though it would look good in literally any other 1940 release) inches towards him. It's not just overwhelming; it's varied, too, coming up with several different ways of socking it to us, sometimes with top-notch effects, sometimes with giant sets, sometimes with bold colors, sometimes just by letting Conrad Veidt chew up all the scenery as the villainous grand vizier Jaffar as other people gawk and puff at him.

What it doesn't have in the midst of all of this is an interesting story or characters, and to be fair, it's almost certainly not something Korda was interested in having. Also to be fair, the 1924 Thief of Bagdad didn't really have those things, either. The difference is that the '24 film has big, ebullient charisma, and the '40 film mostly doesn't. The plot - insofar as it exists or needs to be thought about as more than a pretext - finds Ahmad (John Justin), the sultan of Bagdad, betrayed by Jaffar and exiled, where he has only the help of a wily thief, Abu (Sabu) to survive the various traps Jaffar throws at him. Along the way, he falls in love with a princess (June Duprez), and is magically blinded, while Abu is turned into a dog, which is how we meet them; the film flashes back before it moves forward, at which point the heroes are separated while Jaffar tries to consolidate his power over Bagdad and the princess. With the help of real bastard of a djinn (Rex Ingram), Abu is able to locate Ahmad, and help him get back in time to stop Jaffar.

That's a pretty messy, episodic cluster of stuff, and you perhaps noticed from the way I summarised it how at a certain point the movie starts shifting its attention from Ahmad to Abu. This was unambiguously the right decision: Sabu is ten times the screen presence that Justin is. The problem is that it's still Ahmad's film: he drives the conflict, he has the goals. Abu is just a fun point of identification for the kids in the audience to see somebody about their size go nuts running around and clambering up and down the giant sets. So no matter how much the movie wants to pay more attention to Abu and Jaffar, Ahmad and his nameless princess keep dragging it down. They really are just dreadfully dull - duller even than the human props in the Ray Harryhausen Sinbad movies produced by Charles H. Schneer in the '60s and '70s (the most direct descendants of The Thief of Bagdad, along with Disney's 1992 Aladdin), and those characters represent no kind of insurmountably high bar. The '24 film was mostly selling us spectacle, but it understood that the spectacle had to be glued together, and it had Douglas Fairbank's million-dollar smile to do the gluing. The '40 film suffers from such wobbly story structure that it almost manages to get in the way of the spectacle, even though it has more spectacular crap-per-minute than its forerunner did. I certainly don't meant to suggest that the film somehow magically becomes unwatchable. It most certainly does not: the sheer grandiosity of the thing is undeniable, even if the visual effects show their age, and the elaborately artificial aesthetic isn't remotely fashionable anymore. One could say that they don't make 'em like this anymore, but they never actually did: The Thief of Bagdad was as singular in 1940 as it would be today, and that's worth putting up with some sludgy storytelling and a hugely banal lead actor.

The 1924 fantasy epic The Thief of Bagdad was legendary almost from the moment it was created. By most accounts it was the most expensive film ever made up to that point, and it represented a basically unprecedented achievement in special effects technology. There are individual beats in various Italian and German silent epics that can compete with its best moments, and Hollywood's own Intolerance was still probably grander, but what The Thief of Bagdad can boast that they can't is that it is unrelentingly big. For around 140 minutes, the movie never lets up, never relaxes: it shovels pure, unmitigated SPECTACLE at our eyes, and if we agree that the main draw of Hollywood filmmaking is that it is better than any other at creating spectacular fantasies (especially in the 1920s, when World War I had financially devastated every other internationally significant film industry), then it's fair to say that The Thief of Bagdad is one of the highest achievements, maybe even the highest achievement of silent Hollywood filmmaking.

Remaking it was therefore a somewhat idiotic task, since the point of the movie wasn't "the movie" - it was the gargantuan scope and production value of the thing. So kudos to Hungarian-born British super-producer Alexander Korda: when he decided to produce his own version of The Thief of Bagdad, right on the doorstep of the Second World War, it wasn't "the movie" he was interested in, but the same promise of unprecedented spectacle. Upon its release in 1940, it's fair to say that the world had never, ever seen a special effects extravaganza on the level of the second Thief of Bagdad - 1933's King Kong is a good precedent, but it's the only one I can think of - and with the war about to knock all of human civilisation for a loop, it would be a good long time before that level would be reached. Most notably, it was the first major use of chroma key effects (better known as blue screen or green screen), and while any modern viewer is going to spot the seams without even trying, it's worth reflecting upon how long this stood as the exemplar of cinematic VFX. Looking ahead to the movies that would even attempt to do what The Thief of Bagdad did, let alone improve upon it, it's not until 1953's The War of the Worlds that I even feel compelled to slow down, and I really do think we have to get to the 1960s to find even the best-funded Hollywood productions routinely matching what this movie was up to.

It's not just the groundbreaking effects work, either. Korda, the most profligate producer in the UK at that time, wasn't looking to spare any expenses with the film's overall appearance, and the results is one of the most lavish productions in a generation (so lavish that he needed to finish making it in Hollywood after the coming war made it untenable to keep working at such a vast scale in the UK). The production design, by Korda's brother Vincent, and the Technicolor cinematography, by Georges Périnal, both won Oscars, and it's a dead certainty that if the Academy was giving out awards for costuming at this point, The Thief of Bagdad would have taken that statue too. The film is utterly sumptuous, not in any way attempting to create the illusion of a real place - the sets look like sets, the props look like props - but instead looking to supply an unending litany of lavish delights to glide your eye over, colors to suck in like a thirsty man plunging his head into a desert oasis. And sonically, the film matches its visual marvels with a robust, roiling score by Miklós Rózsa (getting the first of his 17 Oscar nominations for his work; he lost out to Leigh Harline, Paul J. Smith, and Ned Washington, for Pinocchio) that heaves with brassy, exotic instrumentation. I'm not much of a fan of Rózsa's costume drama scores, in honesty; they all sound like the same to me, all big affect with no texture. But The Thief of Bagdad was the one that sounded that way first, and so deserves all the credit for the bigness.

Within this overwhelming aesthetic, the film finds time for several elaborate action-adventure set-pieces, the most impressive of which involves a giant statue over which Korda's favorite child star, Sabu, scurries like a tiny ant while a huge spider puppet (the film's least-impressive effect, though it would look good in literally any other 1940 release) inches towards him. It's not just overwhelming; it's varied, too, coming up with several different ways of socking it to us, sometimes with top-notch effects, sometimes with giant sets, sometimes with bold colors, sometimes just by letting Conrad Veidt chew up all the scenery as the villainous grand vizier Jaffar as other people gawk and puff at him.

What it doesn't have in the midst of all of this is an interesting story or characters, and to be fair, it's almost certainly not something Korda was interested in having. Also to be fair, the 1924 Thief of Bagdad didn't really have those things, either. The difference is that the '24 film has big, ebullient charisma, and the '40 film mostly doesn't. The plot - insofar as it exists or needs to be thought about as more than a pretext - finds Ahmad (John Justin), the sultan of Bagdad, betrayed by Jaffar and exiled, where he has only the help of a wily thief, Abu (Sabu) to survive the various traps Jaffar throws at him. Along the way, he falls in love with a princess (June Duprez), and is magically blinded, while Abu is turned into a dog, which is how we meet them; the film flashes back before it moves forward, at which point the heroes are separated while Jaffar tries to consolidate his power over Bagdad and the princess. With the help of real bastard of a djinn (Rex Ingram), Abu is able to locate Ahmad, and help him get back in time to stop Jaffar.

That's a pretty messy, episodic cluster of stuff, and you perhaps noticed from the way I summarised it how at a certain point the movie starts shifting its attention from Ahmad to Abu. This was unambiguously the right decision: Sabu is ten times the screen presence that Justin is. The problem is that it's still Ahmad's film: he drives the conflict, he has the goals. Abu is just a fun point of identification for the kids in the audience to see somebody about their size go nuts running around and clambering up and down the giant sets. So no matter how much the movie wants to pay more attention to Abu and Jaffar, Ahmad and his nameless princess keep dragging it down. They really are just dreadfully dull - duller even than the human props in the Ray Harryhausen Sinbad movies produced by Charles H. Schneer in the '60s and '70s (the most direct descendants of The Thief of Bagdad, along with Disney's 1992 Aladdin), and those characters represent no kind of insurmountably high bar. The '24 film was mostly selling us spectacle, but it understood that the spectacle had to be glued together, and it had Douglas Fairbank's million-dollar smile to do the gluing. The '40 film suffers from such wobbly story structure that it almost manages to get in the way of the spectacle, even though it has more spectacular crap-per-minute than its forerunner did. I certainly don't meant to suggest that the film somehow magically becomes unwatchable. It most certainly does not: the sheer grandiosity of the thing is undeniable, even if the visual effects show their age, and the elaborately artificial aesthetic isn't remotely fashionable anymore. One could say that they don't make 'em like this anymore, but they never actually did: The Thief of Bagdad was as singular in 1940 as it would be today, and that's worth putting up with some sludgy storytelling and a hugely banal lead actor.