Hollywood Century, 1970: In which an old curmudgeon jumps in with the young turks, and brazen experiment can also be popular entertainment

The New Hollywood Cinema was largely a young man's game, with most of its leading lights part of the first film school generation. Francis Ford Coppola, Peter Bogdanovich, and Michael Cimino were both born in 1939; Brian De Palma in 1940; Martin Scorsese in 1942; Terrence Malick in 1943; George Lucas and John Milius in 1944; Paul Scharader and Steven Spielberg were the babies, born in 1946. We start to creep older with Warren Beatty (b. 1937), Dennis Hopper (b. 1936), Robert Towne (b. 1934), Bob Rafelson (b. 1933), Robert Benton (b. 1932), Mike Nichols (b. 1931), and eventually we land at editor extraordinaire and underappreciated director Hal Ashby, born in 1929.

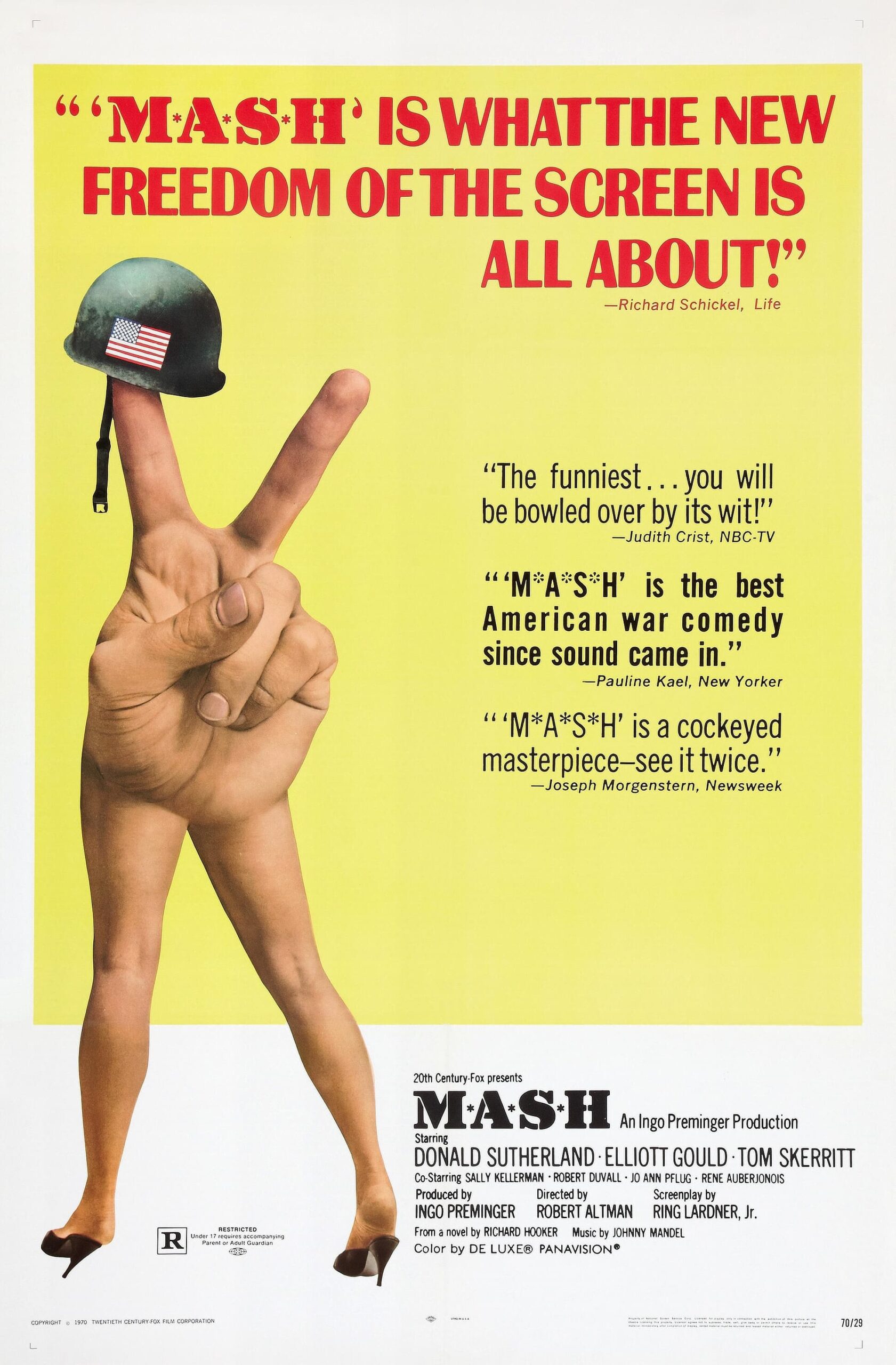

There is one great outlier, not just in age, but in experience: his career had begun in industrial short films a full 20 years before the New Hollywood found him and gave him a chance to explode as one of the most creative, challenging filmmakers of his generation - well, not of his generation at all, of course. The '50s and '60s found him cranking out TV episodes by the handful, and out of all the names I have dropped thus far, he'd be the one who, from the vantage point of 1970, was most clearly part of The Establishment; though he'd do more to demolish The Establishment from inside out than any other American auteur in the most radical decade of American cinema. The man I'm referring to is Robert Altman, not quite 45 years old when he dropped a bomb called M*A*S*H on the cinematic landscape.

I'm going to get the ugly part out of the way, so we can get on to ignoring it: I'm not terribly fond of M*A*S*H. The most impressive things about it were all re-done to better effect and with more sophistication in Altman's later work throughout the decade, and without M*A*S*H's conspicuous flaws of snotty, juvenile humor and a real sense of needless cruelty, both of them typified by it's most signally obnoxious scene, a cheap joke built around the sexual humiliation of the movie's most important female character. It's crude and shaggy and smug, absolutely impossible to square with the wide-open appreciation of humanity's warts and strengths in Nashville, or the complex, ghostly depiction of people outside of the mainstream of self-described Civilisation in McCabe & Mrs. Miller (made just a year later!). As far as depictions of sloppy, self-congratulatory masculinity, The Long Goodbye is infinitely more rewarding.

Of course, Altman could have made none of those films without M*A*S*H paving his way, both aesthetically and commercially. He got to make the film almost entirely without oversight, while 20th Century Fox was far too busy fussing over the more expensive war films Patton and Tora! Tora! Tora! to give much of a shit about the ramshackle little Korean War comedy that the TV director was making with a bunch of nobody actors from a Ring Lardner, Jr. script that he was constantly changing. And he ran with it as far as he conceivably could, making a movie that broke rules, invented rules, didn't give a shit about the rules, captured a specific moment in the Zeitgeist as perfectly as it could be captured, made a huge pile of money, and gave him a blank check to pursue bizarre personal indulgences for years. Glancing over his filmography, it apparently wasn't until the very visible collapse of his film of Popeye, a full ten years later, that he finally ran out of post-M*A*S*H goodwill from the big studio moneymen.

Anyway, having confessed (and felt kind of shameful about it) that I'm no particular fan of the film, I nevertheless admire what it does and what it represents, and I can admit that some of the things I like least about it - it's almost complete shapelessness, for one - are exactly why it made such a tremendous impact in '70. M*A*S*H is not just a mere comedy, not even a mere anti-war comedy - which is all the very long-running, equally iconic TV spin-off is, for all that I prefer the small-screen M*A*S*H to its cinematic big brother - but an entirely self-contained anti-Establishment weapon of mass destruction. It's not enough to mock the serious people who were seriously running the war in Vietnam in to a very serious quagmire: the very object that M*A*S*H is functions as a "fuck you and the horse you rode in on" to the nice, sensible, moderate people who form the Establishment's backbone. The film is laconic and flippant, but mostly it is pissed: it's just that the anger doesn't express itself through the characters and scenario (as the TV show played it), but through the way that the film has been constructed. The messy, busy, discontinuous aesthetic of the film, and its completely ragged non-plot, are acts of aggression against normalcy, suggesting that the world of '69 and '70 were too colossally fucked-up for normalcy to keep going on. Honestly, of all the major early works in the New Hollywood Cinema, it's probably the most important for this reason, along with Easy Rider: plenty of films argued that "This isn't working" and proposed a change socially; these two films were far and away the most prominent and successful attempts at making the same argument cinematically.

It gets there through somewhat less chemically-induced means: the most immediately noticeable thing about the film, even before it's raggedy, extravagantly European editing scheme (credited solely to Danford B. Greene, though Altman was also in the room), is its legitimately revolutionary sound recording and mixing, the most exciting upheaval in Hollywood sound aesthetic since Howard Hawks realised that movies were funnier and more exciting if people's lines overlapped. The sound, by Bernard Freericks and John Stack, is jaw-dropping, and even the refinements made to it by Altman and others (it reached its apotheosis in Nashville) haven't robbed M*A*S*H of its sonic audacity. Offscreen noise is omnipresent, we have to parse two, three, four speakers involved in different conversations simultaneously, and one of the film's most vivid and memorable characters is the P.A. announcer played by David Arkin, who also wrote the pedantic, weird, dreamlike announcements that he speaks in a confused, harried tone, cutting through the action with erratic non sequiturs regularly throughout the movie. Combined with the graceless cutting, which snaps the ends off words and jams scenes together so artlessly that it starts to take on its own internal logic, the overwhelming impression M*A*S*H leaves is that of chaos. It's legitimately edgy in a way that most films that more openly court edginess through sex and violence wouldn't know what to do with, suggesting that war, and society, and human life, and the whole damn thing are messy, inexplicable, and confusing, and coming at a moment of such widespread dissatisfaction as America was feeling in the turnover to the 1970s, it's little wonder that the film grabbed the mood of the nation in a big way.

And that, again, does serve to inoculate the film against the easiest criticisms against what look like enormous problems: I could write hundreds of words about the football game that takes up the last quarter of the not-quite two-hour movie, complaining about the abrupt shift of tone, the hash it makes of at least one character's internal logic, and the weird shift from sly, sardonic hang-out comedy to big goofy antics, but of course M*A*S*H can come right back at me and demand, well, why not end with a ridiculous comic football scene? The Marx Brothers did it, and they were dangerous cinematic anarchists working in a time of mass dissatisfaction too. And while this doesn't make me like the football sequence any more, it certainly makes it impossible to objectively argue against it.

The broad strokes of the film (structure, sound, tone) are so compelling that it's easy to overlook the smaller elements, though only in a film like this could I use the phrase "smaller elements" and be referring to things like the actors, story, and theme. The first of Altman's films with an enormous ensemble, M*A*S*H boasts an extraordinary ensemble: Sally Kellerman, Bud Cort, Michael Murphy, Rene Auberjonois, Tom Skerritt, Robert Duvall, just right off, with the whole thing headed up by Elliott Gould (the closest thing to a big name at the time, on the strength of Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice) and Donald Sutherland as two anachronistically counter-cultural surgeons in a surgical camp in a Korea that Altman was hellbent on convincing us was actually Vietnam (the studio forced him into an opening title card to clarify things, but the intent remains clear). It's a heavily improvised film, setting a standard for Altman films that would continue to the director's death; the result is less a story about character arcs than a collection of events that cause people to react to them, and it's tremendously impressive how well the actors, down to the smallest roles, inhabit their roles with such organic naturalism that it seems right describe it as "people reacting" and not "characters doing X" or "actors doing X". Punctuated with harried, gory scenes of wartime surgery, so the film can give propriety one last smack in the face (it's also the first American studio film with the word "fuck" in its dialogue).

That M*A*S*H is so much of its moment doesn't mean that it's aged poorly. In a lot of ways, frankly, it's brash enough and inventive enough to still feel like a work of radicalism, more than 40 years on - except in matters of social mores; the sexism feels all the more disconcerting for how otherwise contemporary the style is. And the iconic theme song "Suicide Is Painless" - written by Altman's teenage son, and oh, how very teenaged it feels - is unabashedly dated. But these are little things: M*A*S*H is still a wildly alive, rampaging piece of cinema, whatever my own measured response to it, and essential viewing for anyone who cares even slightly about the history of American cinema. Nothing I nor anyone can say makes it less of a milestone or less of a triumph of getting away with it, right underneath the studio's nose.

Elsewhere in American cinema in 1970

-Love means never having to say you're sorry for ruining an entire generation with the treacly bullshit of Love Story

-The Maysles brothers and Charlotte Zwerin's documentary on the Rolling Stones, Gimme Shelter, films the exact moment when the '60s counter-culture implodes

-Hot young film critic Roger Ebert and tit fancier Russ Meyer collaborate on Beyond the Valley of the Dolls

Elsewhere in world cinema in 1970

-Chilean-French director Alejandro Jodorowsky makes El Topo in Mexico, the first of his major spiritual-surrealist epics

-Dario Argento's stylish thriller The Bird with the Crystal Plumage kicks the Italian genre of the giallo into overdrive

-Michael Lindsay-Hogg's documentary Let It Be, shot for British TV but released theatrically, documents in excruciating detail the in-group hatreds that would eventually break up The Beatles

There is one great outlier, not just in age, but in experience: his career had begun in industrial short films a full 20 years before the New Hollywood found him and gave him a chance to explode as one of the most creative, challenging filmmakers of his generation - well, not of his generation at all, of course. The '50s and '60s found him cranking out TV episodes by the handful, and out of all the names I have dropped thus far, he'd be the one who, from the vantage point of 1970, was most clearly part of The Establishment; though he'd do more to demolish The Establishment from inside out than any other American auteur in the most radical decade of American cinema. The man I'm referring to is Robert Altman, not quite 45 years old when he dropped a bomb called M*A*S*H on the cinematic landscape.

I'm going to get the ugly part out of the way, so we can get on to ignoring it: I'm not terribly fond of M*A*S*H. The most impressive things about it were all re-done to better effect and with more sophistication in Altman's later work throughout the decade, and without M*A*S*H's conspicuous flaws of snotty, juvenile humor and a real sense of needless cruelty, both of them typified by it's most signally obnoxious scene, a cheap joke built around the sexual humiliation of the movie's most important female character. It's crude and shaggy and smug, absolutely impossible to square with the wide-open appreciation of humanity's warts and strengths in Nashville, or the complex, ghostly depiction of people outside of the mainstream of self-described Civilisation in McCabe & Mrs. Miller (made just a year later!). As far as depictions of sloppy, self-congratulatory masculinity, The Long Goodbye is infinitely more rewarding.

Of course, Altman could have made none of those films without M*A*S*H paving his way, both aesthetically and commercially. He got to make the film almost entirely without oversight, while 20th Century Fox was far too busy fussing over the more expensive war films Patton and Tora! Tora! Tora! to give much of a shit about the ramshackle little Korean War comedy that the TV director was making with a bunch of nobody actors from a Ring Lardner, Jr. script that he was constantly changing. And he ran with it as far as he conceivably could, making a movie that broke rules, invented rules, didn't give a shit about the rules, captured a specific moment in the Zeitgeist as perfectly as it could be captured, made a huge pile of money, and gave him a blank check to pursue bizarre personal indulgences for years. Glancing over his filmography, it apparently wasn't until the very visible collapse of his film of Popeye, a full ten years later, that he finally ran out of post-M*A*S*H goodwill from the big studio moneymen.

Anyway, having confessed (and felt kind of shameful about it) that I'm no particular fan of the film, I nevertheless admire what it does and what it represents, and I can admit that some of the things I like least about it - it's almost complete shapelessness, for one - are exactly why it made such a tremendous impact in '70. M*A*S*H is not just a mere comedy, not even a mere anti-war comedy - which is all the very long-running, equally iconic TV spin-off is, for all that I prefer the small-screen M*A*S*H to its cinematic big brother - but an entirely self-contained anti-Establishment weapon of mass destruction. It's not enough to mock the serious people who were seriously running the war in Vietnam in to a very serious quagmire: the very object that M*A*S*H is functions as a "fuck you and the horse you rode in on" to the nice, sensible, moderate people who form the Establishment's backbone. The film is laconic and flippant, but mostly it is pissed: it's just that the anger doesn't express itself through the characters and scenario (as the TV show played it), but through the way that the film has been constructed. The messy, busy, discontinuous aesthetic of the film, and its completely ragged non-plot, are acts of aggression against normalcy, suggesting that the world of '69 and '70 were too colossally fucked-up for normalcy to keep going on. Honestly, of all the major early works in the New Hollywood Cinema, it's probably the most important for this reason, along with Easy Rider: plenty of films argued that "This isn't working" and proposed a change socially; these two films were far and away the most prominent and successful attempts at making the same argument cinematically.

It gets there through somewhat less chemically-induced means: the most immediately noticeable thing about the film, even before it's raggedy, extravagantly European editing scheme (credited solely to Danford B. Greene, though Altman was also in the room), is its legitimately revolutionary sound recording and mixing, the most exciting upheaval in Hollywood sound aesthetic since Howard Hawks realised that movies were funnier and more exciting if people's lines overlapped. The sound, by Bernard Freericks and John Stack, is jaw-dropping, and even the refinements made to it by Altman and others (it reached its apotheosis in Nashville) haven't robbed M*A*S*H of its sonic audacity. Offscreen noise is omnipresent, we have to parse two, three, four speakers involved in different conversations simultaneously, and one of the film's most vivid and memorable characters is the P.A. announcer played by David Arkin, who also wrote the pedantic, weird, dreamlike announcements that he speaks in a confused, harried tone, cutting through the action with erratic non sequiturs regularly throughout the movie. Combined with the graceless cutting, which snaps the ends off words and jams scenes together so artlessly that it starts to take on its own internal logic, the overwhelming impression M*A*S*H leaves is that of chaos. It's legitimately edgy in a way that most films that more openly court edginess through sex and violence wouldn't know what to do with, suggesting that war, and society, and human life, and the whole damn thing are messy, inexplicable, and confusing, and coming at a moment of such widespread dissatisfaction as America was feeling in the turnover to the 1970s, it's little wonder that the film grabbed the mood of the nation in a big way.

And that, again, does serve to inoculate the film against the easiest criticisms against what look like enormous problems: I could write hundreds of words about the football game that takes up the last quarter of the not-quite two-hour movie, complaining about the abrupt shift of tone, the hash it makes of at least one character's internal logic, and the weird shift from sly, sardonic hang-out comedy to big goofy antics, but of course M*A*S*H can come right back at me and demand, well, why not end with a ridiculous comic football scene? The Marx Brothers did it, and they were dangerous cinematic anarchists working in a time of mass dissatisfaction too. And while this doesn't make me like the football sequence any more, it certainly makes it impossible to objectively argue against it.

The broad strokes of the film (structure, sound, tone) are so compelling that it's easy to overlook the smaller elements, though only in a film like this could I use the phrase "smaller elements" and be referring to things like the actors, story, and theme. The first of Altman's films with an enormous ensemble, M*A*S*H boasts an extraordinary ensemble: Sally Kellerman, Bud Cort, Michael Murphy, Rene Auberjonois, Tom Skerritt, Robert Duvall, just right off, with the whole thing headed up by Elliott Gould (the closest thing to a big name at the time, on the strength of Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice) and Donald Sutherland as two anachronistically counter-cultural surgeons in a surgical camp in a Korea that Altman was hellbent on convincing us was actually Vietnam (the studio forced him into an opening title card to clarify things, but the intent remains clear). It's a heavily improvised film, setting a standard for Altman films that would continue to the director's death; the result is less a story about character arcs than a collection of events that cause people to react to them, and it's tremendously impressive how well the actors, down to the smallest roles, inhabit their roles with such organic naturalism that it seems right describe it as "people reacting" and not "characters doing X" or "actors doing X". Punctuated with harried, gory scenes of wartime surgery, so the film can give propriety one last smack in the face (it's also the first American studio film with the word "fuck" in its dialogue).

That M*A*S*H is so much of its moment doesn't mean that it's aged poorly. In a lot of ways, frankly, it's brash enough and inventive enough to still feel like a work of radicalism, more than 40 years on - except in matters of social mores; the sexism feels all the more disconcerting for how otherwise contemporary the style is. And the iconic theme song "Suicide Is Painless" - written by Altman's teenage son, and oh, how very teenaged it feels - is unabashedly dated. But these are little things: M*A*S*H is still a wildly alive, rampaging piece of cinema, whatever my own measured response to it, and essential viewing for anyone who cares even slightly about the history of American cinema. Nothing I nor anyone can say makes it less of a milestone or less of a triumph of getting away with it, right underneath the studio's nose.

Elsewhere in American cinema in 1970

-Love means never having to say you're sorry for ruining an entire generation with the treacly bullshit of Love Story

-The Maysles brothers and Charlotte Zwerin's documentary on the Rolling Stones, Gimme Shelter, films the exact moment when the '60s counter-culture implodes

-Hot young film critic Roger Ebert and tit fancier Russ Meyer collaborate on Beyond the Valley of the Dolls

Elsewhere in world cinema in 1970

-Chilean-French director Alejandro Jodorowsky makes El Topo in Mexico, the first of his major spiritual-surrealist epics

-Dario Argento's stylish thriller The Bird with the Crystal Plumage kicks the Italian genre of the giallo into overdrive

-Michael Lindsay-Hogg's documentary Let It Be, shot for British TV but released theatrically, documents in excruciating detail the in-group hatreds that would eventually break up The Beatles